July 6, 2018

Air Date: July 6, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Conservatives Join Climate Agenda

View the page for this story

Recent US efforts to address global warming at the federal level have been hobbled by partisan gridlock, with many conservatives denying climate disruption is a human-induced problem. Now a bipartisan coalition of moderate and conservative Republicans and Democrats is planning a post-election push for a market-based approach to curb emissions. Their ‘Carbon-Dividend’ plan has buy-in from several environmental groups and major fossil fuel companies. Former Senate Republican Majority Leader Trent Lott of Mississippi and former Senate Democratic Deputy Leader John Breaux of Louisiana co-chair the advisory committee of Americans for Carbon Dividends, and Sen. Breaux joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss their efforts. (09:40)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and Host Jenni Doering discuss a $25 million award for the neighbors of some foul-smelling North Carolina hog farms, and the high risk of a disastrously low Lake Mead. In the history lesson, they look back to the gruesome incident a century ago that led to the famous 1976 movie, “Jaws,” and the craze of shark-phobia that followed. (04:00)

The Tide Keeps Rising

View the page for this story

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) charted record high tide flooding along US coastlines in 2017, and they forecast more frequent tidal flooding in the years ahead. NOAA Scientist Gregory Dusek spoke with Host Steve Curwood. (06:30)

Ozone-destroying Chemicals Make A Comeback

View the page for this story

More than 30 years ago, the nations of the world agreed to the Montreal Protocol, which cracked down on chemicals that deplete the upper level ozone layer that protects Earth from dangerous ultraviolet rays that can cause skin cancers. But now emissions of these chlorofluorocarbons are on the rise again. Washington Post Reporter Chris Mooney spoke with Host Steve Curwood about the evidence that suggests industry in East Asia is the culprit. (07:10)

An American Eden: The Lost Garden Underneath Rockefeller Center

View the page for this story

The generation that followed the “founding fathers” had big shoes to fill. So they founded civic institutions like museums, universities, and its first botanical garden to earn the fledgling republic world respect. Historian Victoria Johnson, author of "American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic," spoke with Host Jenni Doering about the foresighted physician who founded the Elgin Botanic Garden in what’s now Rockefeller Center to advance the study of medicinal plants. (15:00)

Mark Seth Lender: Tern About

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

As the light fades on July 4th, Living on Earth’s explorer-in-residence Mark Seth Lender watches two boys angle for a fish dinner on the beach, as a flock of hungry terns comes to feed on their supper of insects. But an unfortunate tangle interrupts the peaceful evening, leaving neither bird nor man unscathed. (03:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: John Breaux, Gregory Dusek, Chris Mooney, Victoria Johnson,

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

This Fourth of July we consider a bipartisan drive that looks beyond the fall elections to solve gridlock on climate change.

BREAUX: This method of putting a fee on those who emit the carbon emissions and then returning that money back to the public is a way to get both sides to come together and actually have a chance of gettin' somethin' done.

CURWOOD: Also, looking back at the goals of a youthful son of the American Revolution.

JOHNSON: If your elders have brought an entire nation into being, what does that next generation do that's heroic? You want to make the nation great; you want to build the civic institutions that will make it stable, that will help fellow citizens live happy, healthy lives.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Conservatives Join Climate Agenda

Shell, BP and Exxon Mobil are among some of the major fossil fuel corporations who have voiced support for a carbon tax and dividend plan to limit global warming emissions. (Photo: Mike Mozart, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The world is looking to the fall elections in the United States to settle or advance some critical issues. Any change of control in Congress might unstick the deadlocked immigration debate and could even lead to impeachment for President Trump. But there is a matter of even greater importance for humanity that a bipartisan coalition is looking to address after the elections. And that is climate disruption. Americans for Carbon Dividends is led by former Republican senator Trent Lott of Mississippi and former Democratic Senator John Breaux of Louisiana. They believe both sides of the aisle can get behind a carbon fee. It would start at $40 a ton to be charged at refineries, mines, wells and ports, with all revenue returned equally to citizens as a dividend.

Senator John Breaux joins us now, welcome to Living on Earth.

Former Senate Democratic Deputy Majority Leader John Breaux of Louisiana co-chairs Americans For Carbon Dividends. (Photo: United States Senate, Public Domain)

BREAUX: Steve, glad to be with you. Look forward to our visit on climate dividends.

CURWOOD: So, tell me. Why do we need a market-oriented plan to fight climate disruption that appeals to conservatives as well as liberals?

BREAUX: Well, the simple answer is the fact that we spent over 30 years trying other approaches and they haven't worked. If you think about it, we've tried the Paris Accord and we've pulled out of that. The Kyoto Protocol back in the 1990s didn't work. The Clean Air Act has not worked like it should have. The cap and trade legislation has not passed, so the answer is that we've tried a whole bunch of different approaches – more regulations from the government to try and limit the amount of carbon we emit into the atmosphere – and so far nothing has worked very well. So, we decided that this method of putting a fee on those who emit the carbon emissions and then returning that amount of money back to the public is a way to get both sides to come together and actually have a chance of getting something done.

CURWOOD: So, why a carbon tax and dividend? Why not simply a tax?

BREAUX: Well, because a lot of more conservative members, particularly on the Republican side, would be against any proposal that has the word tax in it. So, what we're proposing is an entirely different approach. We have approximately a $40 fee proposed on a ton of carbon that is emitted by refiners and those that produce carbon. That would be collected by the treasury, but instead of going into the big pot of money here in Washington to be spent on all kind of different programs, that fee would go back to the American public. Every citizen in the country would be eligible to receive a portion of that fee. The average figure looks like it's about $2,000 for a family of four and that would be every year. So, the companies would not want to have to pay that fee, so they would move to alternative fuels and reduce their carbon emissions because that portion of it they still emit, but to have a fee put on it… But the fee would go back to the people. So, we think it is the best of both worlds. I think we feel that it would get the job done.

Former Senator Breaux grew up on the Louisiana coast and saw the firsthand effects of climate change. (Photo: Ryan Hagerty, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Senator, when did you become, well, deeply concerned about climate change? Being from Louisiana, one might guess Katrina, but you tell me your story.

BREAUX: Well, I lived on the coast of Louisiana, and every year we saw a little bit of our coastline disappear. And unlike a hurricane or earthquake, when you have coastal erosion like we have, that little piece of Louisiana was never coming back. And I grew up in that atmosphere, so we saw it in the real world what it meant to have coastal erosion and we connected it with the climate change and increased weather patterns and increased hurricanes, etcetera. So, I sort of grew up knowing that there was something going on out there that needed to be corrected. And we weren't able to get it done while I was in Congress, but we're still working on these type of projects. So we have a coalition that is now being led by Senator Trent Lott, a Republican who served with me from Mississippi, and myself, along with another whole group of people. This was originally started by Jim Baker and George Shultz, two Republicans who came up with the idea that a market-based approach was much better than a more detailed federal regulatory or regulation type of approach.

CURWOOD: Now, Senator Breaux, why does the proposal call for eliminating some of the EPA regulations including the Clean Power Plan, which President Trump has tried to begin the process of replacing – although I'm not sure that they have had any legal success with that. But why get rid of the Clean Power Plan?

BREAUX: Well, we want to get rid of some of the regulations that won't be necessary if you move forward with a carbon fee of $40 dollars a ton on a carbon emissions, and that fee will be much more effective than the regulatory approaches at actually reducing carbon. So, we're trying to go with the approach that would be most effective and also the one that has a chance of getting passed and adopted by the Congress.

CURWOOD: Now, we've seen the rise of a bipartisan caucus in the house. Carlos Curbelo, the Republican from Florida, has been in the leadership of that calling for climate action. But to what extent do you think the conservative members of Congress will be able to move forward, given that there's so much in the Republican leadership that continues to deny the danger of climate disruption – the science of it?

BREAUX: Well, we have a lot, Steve, already on board. I mean, there's a lot of Democratic support. Sheldon Whitehouse, Senator, is very much in the lead on doing something about climate change. We have Lindsey Graham, for instance, on the Republican side in the Senate who's expressed his support for doing something like this and the direction of helping to reduce the carbon emissions. So, we've got some real leaders that are there already, and you mentioned the Climate Solutions Caucus, which is in the House led by Carlos Curbelo from Florida, of course, and others in the leadership. And many of them are on the actual tax writing committee, the Ways and Means Committee. In the House, they would have jurisdiction over this type of an approach, so there's a base to work with among Republicans in the House as well as the Democrats in the House.

The Climate Leadership Council published “The Conservative Case for Carbon Dividends” to showcase new strategies for climate policy and the Americans for Carbon Dividends committee sprung from this council. (Photo: Courtesy of Climate Leadership Council)

So, this is not going to be a sprint. I mean, I think it's more of a marathon. I mean, I don't want to have something just thrown out on the floor, and if people don't understand it, they're not going to vote for it. But if we can help educate them about what we're talking about and it's a less regulatory, less government-intrusive, free-market type of an approach which has environmental groups supporting it – well, then we have, I think, a very sound basis to move forward with something that could work.

CURWOOD: Sounds to me like you're thinking of after the present fall elections to move this forward.

BREAUX: Oh, absolutely. I mean, it's not going to happen now, but we're going to be spending the time between now and the end of this year meeting with members of Congress and doing op-eds and papers and speaking to journalists like yourself to try and help get the message out – that this is a new approach, there’s a carbon dividend fee that's going to be given back to the American people. And the studies indicate that it could reduce the carbon emissions by three times more than the regulatory approaches, which have not been successful.

CURWOOD: What's been the response of the major fossil fuel companies? I mean, you're from Louisiana. You've worked over the years with ExxonMobil, Shell, BP. What do they say about your proposal?

BREAUX: Well, those are the ones that are doing, because of their refining activities, most of the emissions of carbon, and I think they recognize that something needs to be done. And to their credit, they have become corporate founding members of this effort – companies like ExxonMobil and Total and Shell Oil – and we're pleased to have them on board. I think they can be very effective with more moderate to conservative Democrats and certainly with Republicans as well. But we also have the Nature Conservancy and Conservation International on board, so it's a relatively unique combination that we have behind us and supporting us in this effort.

CURWOOD: Talk to me briefly about the border carbon adjustments aspects of the proposal. When we first spoke about this last year, there was not a trade war in the making, a problem with tariffs. But right now, there's a lot of sensitivity to the US imposing tariffs.

BREAUX: Well, the way it would work, we don't want to have a carbon dividend program in effect in the United States trying to protect the world environment by cleaning up the climate issues – and yet have countries that don't have a similar type of program to reduce their carbon emissions, or be able to export their products into the country and to our country, without having to pay a similar fee. So, what we would do is just say that once our carbon dividend fee is established, that any country that doesn't have a similar type of plan to reduce their carbon emissions – that if they're going to export a product into the United States that has produced carbon emissions in the manufacturing of that product – that they would have to pay a similar fee if they're going to sell those products in the United States. I think it's fair we're not doing something unilaterally but trying to get all the countries of the world working together under our plan.

CURWOOD: Democrat John Breaux represented Louisiana for more than three decades in the US House and Senate. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Senator.

BREAUX: Hey, Steve. We enjoyed it. Let us stay in touch and continue to talk.

Related links:

- Climate Leadership Council

- Americans for Carbon Dividends

- The Wall Street Journal Market Watch | “New conservative PAC to push for carbon tax in U.S.”

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck, “Matitu With Khalifan Matitu (Tanzania)” on Throw Down Your Heart-Tales from the Acoustic Planet, Vol.3, Africa Sessions, Rounder Records]

Beyond The Headlines

Hog farms are abundant in North Carolina and can cause unwanted disturbances such as flies, stench and pollution from the trucks used to transport hogs. (Photo: Kevin Chang, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: We turn now to Peter Dykstra. Peter’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there Peter, how you doing?

DYKSTRA: Oh, hi Jenni. We’re going to talk about a bit of a turn of the tables down in North Carolina, where the hog industry has really held sway over state politics. They just managed to get a law passed in the legislature to make it more difficult to sue hog farms in state court for the nuisance they cause in terms of pollution and smell and everything else. But in a federal court, a jury just awarded 25 million dollars to hog farm neighbors in Duplin county, which is ground zero for the hog industry, for all the trouble that they cause their neighbors.

DOERING: What’s the trouble?

On the Colorado River near Boulder City, Nevada, the Hoover Dam holds back Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the United States by volume. (Photo: Steve Boland, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: The trouble can be anything from flies – you have tens of thousands of hogs, they tend to draw flies for the waste lagoons there – and those waste lagoons stink. Anyone who’s ever driven down I-95, the main highway of the east coast, that’s the place where you have to roll up the windows in North Carolina. There’s also a lot of truck noise and pollution from trucks and from the whole hog process in general.

DOERING: Sounds like a lot of stink for making some bacon.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, there are nine million hogs in North Carolina. That’s nowhere near the biggest – the state of Iowa has 21.8 million hogs. The industry is growing, and even the hogs are growing. The individual hogs are bigger than they used to be.

DOERING: What’s next, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Let’s go out to the desert Southwest, the arid area that relies so heavily on the Colorado River. The Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency that oversees western water, says that there’s an 80 to 90 percent chance that with low rainfall and a heavy drawdown on the Colorado River, we can see a crisis on the river and on the nation’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead.

DOERING: Gosh, that does not sound good. That’s a huge risk.

DYKSTRA: Yes, states are working on a drought plan, but there have been – there’s been a lot of fighting, as there always is over water. Lake Mead and the Colorado are key not just to the growing human populations but to agriculture. Southern California, including parts of LA – you know Las Vegas has for decades been one of the biggest boom towns in the United States, Phoenix and Tucson as well – these towns are expecting to grow, they’re going to need water. They don’t have it.

DOERING: Yeah, but we got to keep the fountains flowing at the Bellagio.

DYKSTRA: At the Bellagio, the golf courses. And of course, we’re dealing with a situation that’s almost analogous to the financial crisis – when banks were said to be too big to fail, and the feds came up with enough money to rescue the banks. Well, I’ll tell you what, there are no new sources of water for the Colorado River and Lake Mead. And for the Southwest, they’re too big to fail.

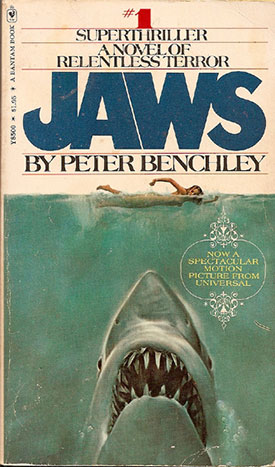

The original cover artwork for Peter Benchley’s novel “Jaws,” which was inspired by a series of shark attacks in New Jersey in 1916 and later led to the 1976 hit movie of the same name. (Photo: Roger Kastel, Wikimedia commons, public domain)

DOERING: So, Peter, what’s up in the history calendar this week?

DYKSTRA: Let’s go back to 1916, a little bit before we had the institution we now know as “Shark Week.” But there was one back even before the US got involved in World War I. July 12, 1916, a young swimmer was bitten in half in a tidal creek in the Jersey Shore.

DOERING: Oh my!

DYKSTRA: One of four deaths that summer. Really freaked people out in New Jersey about the risk of sharks. Interesting, it kind of went away over the decades, but then in the 1970s, the author Peter Benchley used that terror-filled incident to write the best-selling book “Jaws” which became the hit movie “Jaws” in 1976.

DOERING: We got a great soundtrack out of that from John Williams.

DYKSTRA: Got a great soundtrack, and the other thing that happened is it became fashionable to go out and kill sharks. Something even Peter Benchley, before his death about ten years ago, said he deeply regretted from his book.

DOERING: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Thanks so much!

DYKSTRA: Alright Jenni, thanks a lot. And talk to you soon.

DOERING: And there’s more on these stories at our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- The News & Observer | “Jury awards more than $25 million to Duplin County couple in hog-farm case”

- Arizona Daily Star (Tucson.com) | “Risks to Lake Mead, Colorado River intensifying greatly, federal officials say”

- New York Times | “A Century Later, Memories of Fatal Shark Attacks Linger in New Jersey”

[MUSIC: John Williams “Jaws” (Soundtrack from the Motion Picture) [Collector's Edition] 2000 Decca Music Group]

CURWOOD: Next week we look at the future of the US EPA, now that scandal-plagued administrator Scott Pruitt has resigned.

Deputy administrator Andrew Wheeler will take over until someone is nominated and confirmed. Mr. Wheeler is a former chief of staff for Oklahoma Republican Senator James Inhofe, a prominent skeptic of climate science.

DOERING: Coming up – if you think floods are unusual where you live, think again, especially if you live on the East Coast. We’ve got what to watch out for, just ahead here on Living on Earth. Keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck, “Mariam With Djelimady Tounkara (Mali)” on Throw Down Your Heart-Tales From the Acoustic Planet, Vol.3, Africa Sessions, Rounder Records]

The Tide Keeps Rising

Motorists drive through a flooded street near the Lafayette River in Norfolk, Va. The city is one of many East Coast locales with an elevated risk of recurrent high tide flooding. (Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Right now there are no big storms in the Atlantic, and so there is little risk that storm surges will splash into cities and towns along the US East Coast anytime soon. But the tides are another matter. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) says that the number of high tides that flood into Atlantic Ocean communities is about double what they were just 30 years ago, and the agency predicts tidal flooding will keep increasing in the years ahead. Gregory Dusek is a NOAA scientist and one of the authors of the tidal flood report, and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Greg!

DUSEK: Thanks, Steve. Good to be here.

CURWOOD: So, your study focuses on high tide flooding days as opposed to sea level rise. Why look at the high tide flooding in this focused way?

DUSEK: That's a great question. So, I think a lot of people think of sea level rise as something that's not going to be impacting us for some time. Often it's referred to 2050 or 2100 as to when we'll start seeing impacts. But really, high tide flooding is the first evidence that people are seeing of sea level rise, and it's happening right now. And so, we're trying to capture the change that's been occurring in high tide flooding, both in the recent past and in the near future.

CURWOOD: So, what does your report say about high tide flooding then in the US?

DUSEK: So, we're seeing some pretty big increases. Overall, across the US, over the past 30 years on average, we've seen a doubling of the number of days of high tide flooding across the entire country, and then over the past 20 years, we've seen about a 50 percent increase.

A tide gauge in Boston’s Seaport district. This one uses a microwave water level, cone-shaped sensor to measure the water's height. A tide gauge has been at this location in some form since 1921. (Photo: Courtesy of NOAA)

CURWOOD: And so we're not talking about a storm surge or anything. We're just simply talking about the tide that happens twice a day.

DUSEK: Yeah, that's right. So, in many cases, high tide flooding is like a few inches, maybe a foot of water on the streets. You might even see it on a nice day, a sunny day. Often we refer to it as nuisance flooding or sunny day flooding, and so it doesn't take a large storm to occur necessarily. You can have it on seemingly normal days, but what it does is it might influence your commute. It might fill up your storm drainage, affect your drinking water, and really kind of be a nuisance on a day-to-day case.

CURWOOD: Now, I notice that Boston, Massachusetts, where Living on Earth has its studios and offices, is cited as one of the cities that could see record floods. What other cities are most at risk?

DUSEK: Last year in particular, the Northeast was especially hard-hit and that's in part because of the strong Nor'easter season we had last year. So, high tide flooding will be impacted by storm events and by hurricanes as well. So, the Western Gulf in particular had a lot of events last year because of the rather busy hurricane season we had. And then moving forward to this year, we're also looking potentially at an influence from El Niño, which tends to impact the West Coast a little bit more and tends to see a little bit higher water levels. So, we might have some events there. And then in the mid-Atlantic, in particular, it just tends to be one of the greater number of days compared to some of the other locations.

CURWOOD: And then in the trivia department, what cities in the United States have the highest tides?

DUSEK: Boston's is pretty high. It's about 10 feet or so, and then if you go over to the northwest to Seattle and that range in the Pacific Northwest, in that area, you get up around four meters or so. So, about 12 to 15 feet from low to high tide.

CURWOOD: How did you get the data for this report?

DUSEK: So, our office is the Tides and Currents office at NOAA, and we run over 200 real-time tide gauges across the US. And in many cases they've been operating for 50 years or more, and we have several locations that have been operating since the 1800s. And so we're able to use that data to look at changes in sea level over time and changes in the tides and high tide flooding over time. So, really having this water level network and this consistent continuous high quality water level data is what makes this possible.

CURWOOD: So, which communities are most at risk from high tide flooding right now and among those communities, which ones didn't really have this problem 20, 30, 40 years ago?

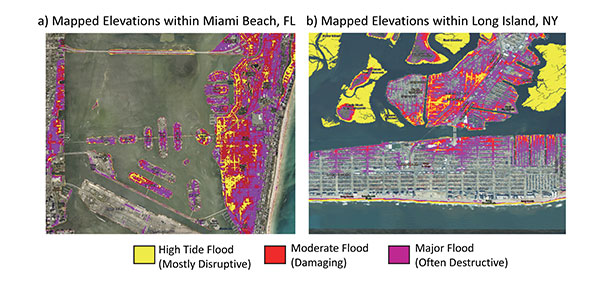

A map of elevations at or below nationally consistent flood severity levels for high tide flooding. (Photo: Courtesy of NOAA)

DUSEK: So, some of our tide gauges have been in for a hundred years or more. You look at communities along the East Coast in particular. I think a good example is Charleston, South Carolina, where if you go back 30 years, you were having maybe one day a year of flooding. And in the case of Charleston, we’ve had a tide gauge there since 1921. And in 1928, we had the Lake Okeechobee hurricane, which is one of the deadliest hurricanes in US history. It was a Category 1 storm when it hit Charleston, and that was the highest recorded water level at our Charleston gauge from 1921 to 1934. So, we had one high tide flood in the first 14 years at Charleston, and it was caused by a catastrophic hurricane, and now we see it four times a year or more. And so, the water levels that used to take a once-in-a-decade storm now occur just from normal weather and multiple times a year.

CURWOOD: Greg, how much trouble are we in with this high tide flooding and sea level rise in the years ahead? We have a rising population here. A lot of folks live on the coastline. Well, looks like there's trouble ahead.

DUSEK: Yeah, I think major urban areas which are along the coast are going to be experiencing flooding on a very frequent basis, at least as the construction and flood defenses are set up right now. We're headed towards flooding of every other day, 180 days per year, especially by 2100. In 2100, even at the intermediate low scenarios, most places in the northeast Atlantic, southeast Atlantic, the gulf will be seeing flooding every other day. It's definitely going to be a reoccurring problem that people are going to have to deal with. And it's going to get more frequent and it's going to get worse in terms of its magnitude.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about what you hope municipalities will do with your research as they draft plans to deal with future flooding.

DUSEK: So, one of the reasons we put this together really is to provide people with the most up-to-date information they can have about how much flooding they're seeing and what they can expect not just next year but even further into the future. And the idea is that hopefully they will take this and incorporate this in their planning moving forward, especially if we want to avoid cases where we're going have water in the streets almost on a weekly or even more basis – then, you know, this information is going to be vital to folks making those type of decisions.

CURWOOD: Gregory Dusek is Chief Scientist at NOAA's Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services. Greg, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

DUSEK: Thanks, Steve. It was great talking to you.

Related links:

- Read the full NOAA report here

- NOAA: "What is a tide gauge?"

- Inside Climate News | “U.S. Coastal Flooding Breaks Records as Sea Level Rises, NOAA Report Shows”

[MUSIC: Jan Johansson, “Gammal brollopsmarsch” on Jazz Pa Svenska, Heptagon Records]

Ozone-destroying Chemicals Make A Comeback

We need the stratospheric ozone layer — it’s the region of the earth’s atmosphere that absorbs dangerous ultraviolet radiation. (Photo: Chani Goering, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

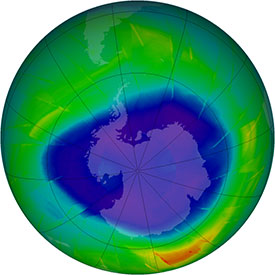

CURWOOD: The Ozone Hole used to be an issue from the past. Nations of the world came together over 30 years ago under the Montreal Protocol to crack down on chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, chemicals used for refrigeration and foam manufacturing. Trouble is, when CFCs escape in the air, they rise up and rip holes in the thin layer of stratospheric ozone that protects us from ultraviolet radiation that can cause skin cancers. So, the Montreal Protocol mandated alternatives that don’t deplete the ozone layer, and for years the ozone holes have been healing. But recently NOAA found that CFC levels are on the rise again. Chris Mooney is an environment reporter for The Washington Post. Welcome to Living on Earth, Chris!

MOONEY: It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, how important is the health of the stratospheric ozone layer to the well-being of the planet and those of us who live on it?

MOONEY: It's vital. It's one of the vital parameters of the planet. And it's also, I guess, symbolic in the sense that humans, through incredible ingenuity, created these substances that didn't exist in nature and that were really powerful and durable, which they needed to be because of the role that they were going to play in the industrial applications they were intended for. Wow, we made them so strong that nothing destroyed them until they reached the stratosphere way, way above our heads. And it was only there that they could be destroyed, and when that happened, they created a chain reaction that destroyed ozone and, in turn, endangered us. So, it was this symbol of the incredible reach of human industry and its ability to have unintended effects that reverberate around the whole planet.

CURWOOD: And recently you reported on this mysterious rise in emissions of the ozone destroying chemical CFC-11, and where they might be coming from. What caused the NASA scientists to look into the rise of CFCs in the first place?

MOONEY: Well, what's actually happening here is that in pursuit of the agreement of the Montreal Protocol, there's monitoring going on all the time as scientists attempt to ensure that the chlorofluorocarbon levels are declining as expected.

Former US Secretary of State John Kerry delivers remarks during a plenary session of the conference about amending the Montreal ozone layer protection protocol held on October 14, 2016 in Kigali,Rwanda. (Photo: By U.S. Department of State from United States [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: So, in other words, Chris, these are cops on the beat making their usual rounds keeping track to be sure that all the doors were metaphorically locked for ozone depletion – but in this case apparently they're not so locked.

MOONEY: Exactly. So, one of the numerous gases that was phased out and then later banned under the Montreal Protocol – CFC-11 it's called, or Trichlorofluoromethane – scientists noted that it wasn't going down as they would expect as the molecule gets destroyed in the stratosphere. It wasn't going down as fast as they expected for about a decade between 2002 and 2012, and then it started going up. At that point, they were pretty concerned because that kind of behavior needed to be explained.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, how surprised were they to see this rise?

MOONEY: To hear them talk – I've got some quotes in my story about this of the genre of “this is a really shocked scientist.” I forget the exact words, but this is not something that you see every day. It's not what should happen under the Montreal Protocol, and there's not any obvious immediate explanation for it. So, they had to go and start trying to test possible explanations, and in the course of ruling things out, they were left with the conclusion that probably somebody is making it.

CURWOOD: So, what are the prime suspects of folks who could be making this stuff again?

MOONEY: Well, they were only able to say that it seems like it's coming from east Asia, and they were able to say that because some of the atmospheric measurements are taken in Hawaii, Mauna Loa Observatory, which is sort of famous because that's where they also measure atmospheric carbon dioxide. And essentially they were finding concentrations of CFC-11 mixed in with other gases that they said were characteristic of an east Asian source.

CURWOOD: So, I'm looking at a map of east Asia. The biggest country there is China.

MOONEY: Yes. And for population and for industry, etcetera, they're much larger. So, first of all, you would expect there to be existing… – you know, as I said, not all CFC-containing substances have been destroyed or retired, etcetera. There are some that still could be broken down, recycled, put in a landfill, lead to emissions. You would expect most of those probably to be in the biggest country too. But scientists don't think that it's just the retirement of old appliances and old buildings that is leading to this.

CURWOOD: So, the use of these chemicals is not permitted under the Montreal Protocol and the various things that have been added to it. What's taking place in terms of enforcement to minimize this type of problem?

MOONEY: Well, I think the first thing that happens is that the scientific panel of the ozone treaty – the Montreal Protocol, which is implemented by the United Nations Environment Agency – is going to be vetting this very closely. And then the question is, what do they do if they find a source? Without a source, there's no enforcement, so they have to do still more data gathering first. And if they find a source of new emissions, then I think it really becomes a diplomatic question, and officially, countries are not… nobody’s reporting this production. So, what would happen if this production is occurring in some country that's not reporting it? Presumably it would not be something that the country actually wants to happen – that's a presumption – but it's something that's happening outside of their control. And so all the other countries would lean pretty heavily on that country to make it stop.

CURWOOD: So, what if somebody says, hey, this Montreal Protocol thing isn't working. What's the right answer based on the facts as we know it right now?

This composite image depicts ozone concentrations above the Antarctic in 2009 in Dobson units, with purple and blues regions depicting severe deficits of ozone. While atmospheric ozone continues to recover, the rise of CFC-11 hampers that progress. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MOONEY: That seems like that would be too far. In fairness, it is one of the first really big questions being raised about what was seen as sort of the most powerful, most effective environmental treaty that we had. And this does definitely lead people to say, OK, maybe it wasn't what we thought. But what I'm hearing is, no, that doesn't seem to be justified conclusion yet, because now is the moment when the Montreal Protocol would actually kick into action. So, if they don't find the source, if they aren't able to make the source cease, then I think you would question it. But what I'm hearing is that just the fact that they detected it, gears are turning to create action, shows that the protocol is acting in the way that it's supposed to.

CURWOOD: Chris Mooney is a reporter for The Washington Post. Chris, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MOONEY: Great to talk with you.

CURWOOD: After we spoke with Chris, the New York Times published a story suggesting foam insulation makers in China are the likely sources of CFC-11 emissions.

Montreal Protocol officials have yet to comment, with the next meeting of its noncompliance committee scheduled for July 8th in Vienna, Austria.

Related links:

- Washington Post | “Someone, somewhere, is making a banned chemical that destroys the ozone layer, scientists suspect”

- New York Times | “In a High-Stakes Environmental Whodunit, Many Clues Point to China”

- The Montreal Protocol

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, “Flight Of the Cosmic Hippo” on Flight Of the Cosmic Hippo, Warner Bros.]

DOERING: Coming up – Alexander Hamilton and the birth of botanical medicine among America’s revolutionaries. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at race to nine billion dot com. That’s race to nine billion dot com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[Sonny Terry, “Harmonica With Slaps” on The Folkways Years, 1944-1963, Smithsonian Folkways]

An American Eden: The Lost Garden Underneath Rockefeller Center

Elgin Botanic Garden, unknown artist, c. 1815. (Image: Xocolatl, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

In 1776, fifty-six patriots signed their names to a bold document that planted the seed of a new nation, and men like Franklin, Adams, and Jefferson became the “founding fathers.” Less famous is the generation that followed. The Americans who grew up just as the Revolution unfolded saw that the young, fragile democratic experiment would need civic institutions: museums, universities, and even botanical gardens. The Elgin Botanic Garden was once in the heart of what’s now Midtown Manhattan. It was the life’s work of a well-known doctor and medical botanist, David Hosack. Historian Victoria Johnson has written “American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic.” Victoria, welcome to Living on Earth.

JOHNSON: Thank you. I'm so happy to be with you.

DOERING: So, David Hosack isn't a household name, but it's also clear from your book that he helped shape America in the republic's early years. So, who was he?

JOHNSON: David Hosack was the most famous man most of us have never heard of. If he's known at all, it's for having been the attending physician at the duel with Hamilton and Burr. He was chosen by both men. But that was only one of many, many things he became famous for, including founding the first botanical garden in the new nation. He was the reason that New York became New York in his generation, the premier city for the arts and sciences. He was a founder or co-founder of the New-York Historical Society, Bellevue Hospital, the city's first obstetrics hospital, its first mental hospital, its first public schools, its first school for the deaf, its first subsidized pharmacy for the poor, and on and on and on.

American Eden is Victoria Johnson’s third book. (Image: courtesy of W.W. Norton)

Hosack was a teenager walking through New York City, passing people like Hamilton and Burr and George Washington and Thomas Jefferson on the street in New York City. He grew up as a very young child under the British occupation of Manhattan. He saw heroism and sacrifice all around him, and what does that next generation do that's heroic? If your elders have brought an entire nation into being, what do you do as a teenager, what do you aspire to? If you're David Hosack and many of his peers, you want to make the nation great, you want to build the civic institutions that will make it stable, that will bring it world respect, that will help fellow citizens live happy, healthy lives.

DOERING: How did you come across his story, and what inspired you to write this book?

JOHNSON: I love the natural environment, and as a professor who specializes in the history of organizations, I was fascinated to read a description of a couple of pages of David Hosack and his lost garden at the heart of Manhattan. I read it in a wonderful book about the founding of the much later New York Botanical Garden – that was founded 90 years later in the late 19th century – and that story grabbed me from that first second, and the more I learned about him, the more I realized that he was truly a great forgotten American.

DOERING: And in the midst of all that research, we have the musical “Hamilton” which just exploded. And he had this connection with Hamilton. Can you talk a little bit about that?

JOHNSON: Yes, in 1797, so seven years before the duel, Hosack had been called in to a dire situation facing the Hamilton family. Hamilton's son Philip was stricken with a terrible fever, and Hosack saved Philip Hamilton's life by doing some unusual risky things for the time which involved drawing a steaming bath and sprinkling in Peruvian bark, a botanical remedy. Normally, the choice would have been bloodletting or mercury or cold cloths to try to lower the fever. And when Hosack had gotten Philip out of danger, he retired to a bedroom in the house. He wanted to stay in the Hamilton house to make sure that Philip was all right. And he fell asleep, and he woke up suddenly to find Alexander Hamilton at his bedside, kneeling, with tears in his eyes. He took his hand and thanked him for saving the life of his very precious eldest son Philip. And that episode earned Hosack Hamilton's trust and gratitude, and Hosack became Hamilton's family physician.

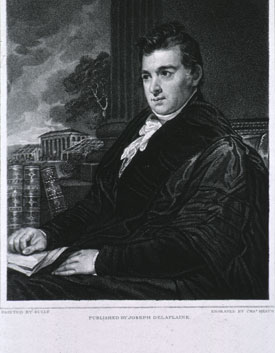

David Hosack with his botanical garden in the distance (now Rockefeller Center), by Charles Heath, engraving, 1816. Collections of the National Library of Medicine.

DOERING: Hosack seemed to have this faith in botanicals and plants to help with medical remedies. How revolutionary was that? And where did he get that from?

JOHNSON: There was some attention to botanical remedies among doctors with whom Hosack studied, when he studied in New York and in Philadelphia as a very young man. But they were mostly thought of as supplies to be bought at apothecary shops. A lot of the medications were imported, such as Peruvian bark, the most powerful of the contemporary medicines. And they were also used in conjunction with much more radical and sometimes deathly treatments like mercury, which is toxic. And American medicine was still far enough behind European medicine that many of his doctors had trained in Great Britain. So, he decided to sail to Edinburgh himself. It was there that he discovered his life's other great passion – botany. He discovered that Europe was blanketed in botanical gardens, and that for European doctors and medical professors, botanical gardens were laboratories, classrooms, and encyclopedias, all rolled into one. That was where you trained students in medical botany. But what Hosack learned, in addition to falling in love with botany, he learned that no one really knew how to isolate, how to identify new plant-based medicines. And when he returned to the United States two years later, after a full year of daily medical botany training, he was obsessed with the idea that the North American continent was blanketed in undiscovered medicinal plants.

DOERING: So, he comes back to the United States and begins practicing medicine. What does he do next?

JOHNSON: Hosack was appointed a professor of botany and medicine at Columbia [University] shortly after he returned, and he taught his students as best he could out of books, taught them medical botany. He told his students that a doctor must know his foods and medicines from his poisons, but he felt incredibly frustrated that he couldn't teach his students using actual plants. So, he lobbied Columbia for funds to launch a botanical garden, and they said yes, but they were pretty cash-strapped. Finally, he just bought 20 acres of land with his own money. He went three-and-a-half miles north of New York City to buy this land to rural Manhattan, and he would ride up this country lane called the Middle Road into rolling hills, farms. The woodlands of Manhattan had largely been cut down, but there were still groves, and he could see both rivers and mountain laurel and wild grasses and wild flowers. It was completely pastoral, and he decided that if he launched the garden by himself, his fellow citizens would eventually come to their senses and make it truly a public garden.

DOERING: So, I'm wondering what came of his vision to create this botanical garden where physicians could study the medical properties of plants. How useful did it become?

JOHNSON: The garden – it brought Hosack great renown. And Hosack accomplished several things with the Elgin Botanic Garden. He trained an entire generation of doctors not only in how to care for their patients and the medical uses of particular plants, but he also taught them the scientific method.

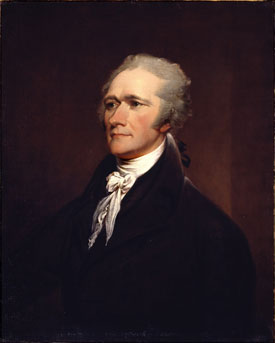

The portrait Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull, oil on canvas, 1806. David Hosack was Hamilton’s friend and physician, and tended to him after the fatal duel with Aaron Burr. (Photo: Collections of the National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

He trained them in such a way that when medicine moved on after his death more towards the chemistry laboratory and away from botany, he had equipped a whole generation of medical researchers in how to pursue their questions and find answers. He also brought in to being a generation of a professional American botanists where there had been pretty much none before. Most people studying botany in the early republic were gentleman polymaths or they were sort of collectors collecting for nurseries for commercial purposes. And it was Hosack's students and their students who went on to found botanical gardens across the country. The founders of the great New York Botanical Garden were students of Hosack's prized students – so, Hosack's intellectual grandchildren. So, the New York Botanical Garden was founded in the 1890s, and he is present everywhere you go in the garden today, the New York Botanical Garden. The devotion to collecting plants from all over the world, to understand ecosystems around the world, to education of New Yorkers and international visitors… He is everywhere there – his spirit and what he dreamed of – and I love walking around that glorious garden and thinking how happy Hosack would be if he could see it.

DOERING: It was so heartbreaking reading about the collapse of Elgin, this dream and this paradise, this American Eden that he had built in what was then the country of Manhattan, but what is now Rockefeller Center. Why did it happen? Why did it collapse? And what did that mean to him and to his fellow Americans who wanted this garden to be successful?

JOHNSON: He did have a moment of triumph where he managed to get public funding. He lobbied for an entire decade to get the state of New York to take it over and run it as a public institution. He was in debt constantly, but he kept pouring his own money into this institution because he believed in it so much. And he eventually spent more than a million in today's dollars on it out of his own pocket. So, he did have this pinnacle of success in around 1810. He was able to persuade the state of New York to pass an act purchasing the garden to run for the public benefit.

Hosackia stolonifera (Creeping-Rooted Hosackia), from Edward’s Botanical Register, vol. 23 (1837).

So, he actually triumphed. He got what he had always wanted, which was not to build a garden for his own glory but to build a garden for his fellow citizens. The aftermath of that is the garden was given to Columbia College to run for the public benefit. Hosack soon realized to his horror that Columbia wasn't committed to maintaining the garden, in part because of its incredible expense. The garden collapsed. They looked the other way while the caretaker took plants and sold them downtown in a shop, and the conservatory fell apart. The glass panes shattered on the floor, and his arboretum was ripped out and carried up the island to beautify a new insane asylum that was being built. So, he watched the garden fall apart, and this was incredibly painful to him. But he had a great sense of humor and he also had a great sense of drama. And after trying over and over to get the garden back from Columbia – to lease the land back and recreate the garden – he made a purchase which, I think, was his way of saying, I'm moving on. He purchased from a young friend one of the most famous paintings from American history, the “Expulsion from the Garden of Eden” by Thomas Cole. And Cole was a young painter at the time trying to sell this painting, and Hosack ran into Cole in the street shortly after he had finally given up on getting the garden back, and he made Cole an offer on the spot. And Hosack was obviously the most suitable owner in the United States for this painting.

DOERING: Walk us through the transformation of what had been the Elgin Botanic Garden into Rockefeller Center.

JOHNSON: Columbia held on to the land and began to realize that the land was going to be a pretty valuable piece of real estate. As the city grid rolled up the island, the Middle Road, this country lane was renamed Fifth Avenue. Streets were cut through the land running across Hosack’s old fields of grain and in front of his conservatory. And Columbia leased the land to developers, and by 1870, Hosack’s 20 acres was completely covered by apartment buildings. In the 1920s, that land caught the eye of John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had grown up very near the former garden land.

-Yanka-Kostova.jpg)

Victoria Johnson is an Associate Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College in Manhattan, where she teaches on the history of New York City. (Photo: Yanka Kostova ©)

The neighborhood was noisy. There was an elevated train that was filled with speakeasies. It was not a beautiful neighborhood. And John D. Rockefeller Jr. began dreaming of a new complex of commercial and cultural buildings that would be centered on an opera house. The Great Depression hit. He went ahead anyway, and he built Rockefeller Center. The opera house fell by the wayside in the project but became Radio City Music Hall, and in 1985, Columbia sold the land to the Rockefeller Group for $400 million. The land had been leased the entire time from the 1920s to the 1980s. The land changed hands a couple of times after 1985, but around 2000, it changed hands again for almost two billion dollars. And you can stand in Rockefeller Center today, and if you close your eyes and think really hard into the past, you are standing in the middle of a 20-acre botanical garden.

DOERING: Victoria Johnson is an Associate Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College in New York City. Thank you for your time, Victoria.

JOHNSON: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic

- About author Victoria Johnson

- New York Botanical Garden | “Rockefeller Center: Botanical History Underfoot”

- About the Hamilton-Burr Duel

- Hosackia is a genus of flowering plants in the legume family

[MUSIC: Peter Ostroushko, “Psalm Of the Prairie” on A Film By Ken Burns - The National Parks: America’s Best Idea (soundtrack), PBS]

Mark Seth Lender: Tern About

Air-bound tern. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: The Fourth of July was a special day at the beach for Living on Earth’s explorer-in-residence Mark Seth Lender, but it wasn’t about a barbeque or lazing in the sun to get some vitamin D.

LENDER: Summer late in the day. The clouds on the horizon are raked coals, row upon row, and a green gold fills the spaces in between. Two boys surf cast from the rocks where the marsh edges into the sea. Spider webs of ten-pound line, the boys in silhouette against the orange light and its reflection on the water.

And a flock of common terns appears, all flying like swallows. There must be insects on the air, too small to see, and the terns have come to feed.

Not the best of signs.

How much nourishment? Some. Or maybe something particular they need. But they have come far, there is no colony for miles and indeed the fishing has been thin all this year – the boys for all their persistence catch nothing. The chicks on the nest must be hungry. Hunger is the draft that sends the terns aloft and does not let them land.

A common tern and newborn chick. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Terns skim the pull of the swell. The quick wavelets that lip-lap-lup into the spartina end in a hush upon the sand. The fishing lines fan out. The birds flash. The sunlight flares then fades to an ember. The inevitable comes to pass: a tern has tangled in the line.

Now in the water up to my knees, bare feet banging rocks but do not feel it; nor the unseasonable cold; nor see the people who crowd in:

Only the tern, only the line.

Fingers slipping, light failing, bird kiting out of control.

- And grab -

- And hold -

Hauling, winding, reeling hand over hand.

- To fold -

- His wings -

To keep them from breaking!

Grrrahking! and Screeking! the red beak seeking the black cap the white head twisting then reaching - Clamp! - on the skin of the wrist where the veins are pulsing. The man (who is me) feels the pinch but pays no mind, his mind only watching, a silence of untangling, fingers that are scrambling, an event that unfurls - on its own - that a singular purpose drives:

Part the line!

He questions far back in his mind:

Is there hurt is there harm will it heal is there time? There are young to feed and fish to find and Ah! The soft of the feathers! His hands like steel and leather of some mechanical arcade crane reaching at a distance for the prize that the man (who is me) must unbind:

A tern close-up. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Part the line!

Like a snare!

- SNAP! -

- Unbound!

And from the cradle of my arms the bird –

Flies!

CURWOOD: And don’t forget, if you see discarded fishing line on the shore, please take a moment to pick it up and make sure it won’t tangle some creature. It’s a wonderful and kind thing to do.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender's Field Note: Fishing Line Endangers Birds

- Listen to another story about Terns from Mark

[MUSIC: Django Reinhardt Festival Band, “Manoir de mes reves”]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Savannah Christiansen, Anna Gibbs, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Maggie O’Brien, Aynsley O’Neill, Sarah Rappaport, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page – PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood – thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth