April 12, 2019

Air Date: April 12, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

‘Mayor Pete’ and the Climate

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Pete Buttigieg, the 37-year-old Democratic mayor of South Bend, Indiana, is riding a wave of media attention as he campaigns to be the next United States President. He’s making the future of America a focal point of his campaign. On April 5th, “Mayor Pete” spoke at the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, NH and highlighted climate change as a key concern for his generation. As Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering reports, that message resonates with those young and old voters who see Mayor Buttigieg as uniquely qualified to talk about the future of America. (06:16)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week in beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra joins host Steve Curwood to discuss good and bad news about plastics in the oceans and freshwater. The conversation continues with the story of a rhino poacher in a South African park trampled to death by an elephant and later eaten by a pride of lions. Then they look back in the history calendar to discuss the 40th anniversary of the Environmental Protection Agency’s formal ban of the manufacture of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). (05:04)

Fearsome Bull Elephant Musth

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Bull elephants reach maturity at about 20 years. Typically, these bulls are gentle giants, who reside at the edges of the herd. That all changes during mating season when they come into musth. As Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender tells us, when that happens bull elephants can become a force of nature. (02:50)

Science Note: Can Plants Hear?

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Flowers don’t have ears like ours, but recent research finds that some flowers, like evening primrose, can “hear” the buzzing of bees’ wings. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports on how these flowers sometimes quickly respond to nearby pollinators by sweetening their nectar. (02:02)

Pesticide Risks Ignored at Trump Interior Dept.

View the page for this story

Former oil and agribusiness lobbyist David Bernhardt is the Trump Administration’s new Secretary of the Interior, and like his predecessor Ryan Zinke, he’s already dogged by allegations of ethical missteps from his time as Deputy Secretary that started in 2017. Recently over 84,000 pages of documents have surfaced alleging Secretary Bernhardt's interference with a U.S. Fish and Wildlife report on the risks certain pesticides may pose to endangered species. Brett Hartl, the Center of Biological Diversity’s Director of Government Affairs joined host Steve Curwood to talk about the dangers of the pesticides chlorpyrifos, malathion and diazinon for endangered species and other species alike. (10:27)

BirdNote®: Sage Grouse Lek and Grasslands

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Springtime brings spectacular courtship dances by the male Greater Sage Grouse, which sings a remarkable song as it puffs up its two bulbous air sacs and moves its head back and forth in order to attract a mate. BirdNote’s Michael Stein reports on the bird’s curious practice called leks, and how Sage Hens are threatened by agricultural and energy development. (02:18)

The Sage Hen and the Sage Brush

/ Clay ScottView the page for this story

We revisit an earlier Living on Earth report about the threats to the Greater Sage Grouse from oil drilling, grazing, and invasive plant species. Living on Earth’s Clay Scott reports on the debate between conservationists and private landowners about how best to protect this dwindling species and the sagebrush ecosystem on which it depends. (09:08)

Greater Peril for the Greater Sage Grouse

View the page for this story

In 2015, private landowners, federal agencies and conservation groups worked out a plan to protect the Greater Sage Grouse by placing some restrictions on grazing and oil and gas drilling in ten Western states. But the Trump Administration recently lifted those restrictions, leaving the Sage Grouse and other sagebrush-dependent species more vulnerable. Collin O’Mara, the President and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation, joins host Steve Curwood to explain his concerns. (08:19)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Brett Hartl, Collin O'Mara

REPORTERS: Jenni Doering, Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Clay Scott, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Democratic Presidential hopeful Mayor Pete Buttigieg is speaking out about the dangers of climate change.

BUTTIGIEG: Speaking to you as a mayor who found myself compelled to open the emergency operations center of my city twice in 2 years for floods that we were told were 500 to 1000 year floods, happening back to back – don’t tell me climate is not a security issue.

CURWOOD: Also the Trump Administration moves to lessen protections for the once abundant Greater Sage Grouse.

HARKNESS: They would come in here right around the first of July, just thousands and thousands of them. I’ve seen them flying-- I don’t know how many you’d see, hundreds of thousands. You can see in any direction that’s open there. As far as you could see, there would be sage grouse walking, eight to ten feet apart.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

‘Mayor Pete’ and the Climate

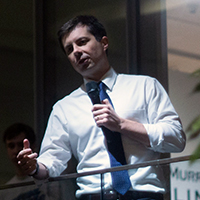

South Bend, IN Mayor Pete Buttigieg spoke at the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire on April 5th, 2019. (Photo: Marc Nozell, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The presidential primary season can have its surprises, and one for the Democrats this year is the 37-year-old mayor of South Bend, Indiana, Pete Buttigieg. His fans call him Mayor Pete and he was virtually unknown just a few weeks ago, but this Rhodes Scholar and veteran of Navy intelligence is riding high on a wave of media attention. Of course there is more to a presidential campaign than excitement, but it’s hard to win without it, and when Pete Buttigieg came for an appearance at the Currier Art Museum in Manchester, New Hampshire there was an overflow gathering outside. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering has our story.

[APPLAUSE, CHEERS]

DOERING: There was a crowd of at least a hundred people who weren’t able to get in to the venue, so “Mayor Pete” stood on a bench outside, and revved up the crowd.

CROWD [CHANTING]: Pete! Pete! Pete! Pete! Pete!

BUTTIGIEG: I’m really humbled you took the time to spend with me and really appreciate your motivation to help bring about something that will not only win an election, but help us begin to win an era.

[CHEERS]

DOERING: For the 300 or so who did make it inside the Currier Museum, the atmosphere was buoyant.

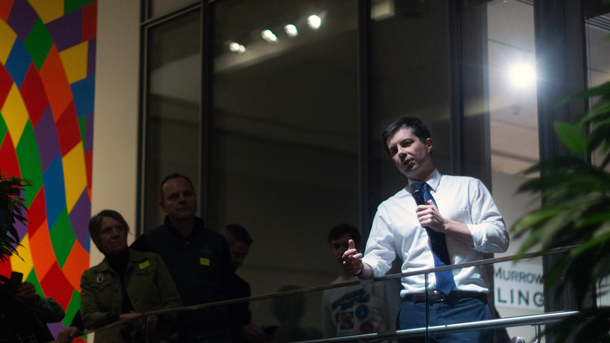

An overflow crowd of at least a hundred people stood outside the Currier Museum, April 5th and Pete Buttigieg came out to speak with them before heading back inside. (Photo: Jarred Barber)

[MUSIC: “Freedom! ‘90”, George Michael, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 (Columbia 1990)]

[CHEERS]

DOERING: Mayor Buttigieg highlighted the importance of looking towards the future, especially when it comes to the effects of climate change.

BUTTIGIEG: Speaking to you as a mayor who found myself compelled to open the emergency operations center of my city twice in two, years for floods that we were told were 500-year to 1000-year floods, happening back to back – don’t tell me climate is not a security issue.

DOERING: Mayor Buttigieg didn’t mention the Green New Deal here in New Hampshire, but at a rally in Boston in early April, he said he supports the plan to decarbonize the U.S. economy and fund clean energy jobs. He compared the ambitious plan to the moon shot.

BUTTIGIEG: In the same way that President Kennedy hadn’t mastered all the rocket trajectories in 1960 when he wanted us to get to the moon by 1970, right, I still think we commit to it now, precisely because we’re not sure how to get there but we gotta kind of tie ourselves to that goal and then do everything we can as a country to get there, because I simply don’t believe we can afford to wait. [CHEERS]

DOERING: President Kennedy was our youngest president at 43 years old. Mayor Buttigieg is just 37 and says his age makes him uniquely qualified to take on the issue of climate change as president.

BUTTIGIEG: If this generation doesn’t step up, we’re in trouble. [APPLAUSE, CHEERS] This is, after all, the generation that’s gonna be on the business end of climate change for as long as we live. [APPLAUSE]

“Mayor Pete” met with dozens of New Hampshire voters April 5th in the Currier Museum after his speech. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: In 2017 the South Bend, Indiana mayor joined the Mayors National Climate Action Agenda. That’s a group of hundreds of mayors who have pledged to work in their cities to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to meet the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement.

He’s made redevelopment and urban livability key priorities for his city. His “Smart Streets” program, which widened sidewalks and added new bike lanes and urban trees, has been credited with revitalizing South Bend’s downtown. Mayor Buttigieg says the greening of South Bend helped attract over $90 million in private investment.

And when President Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency scrubbed climate change data from its website in 2017, South Bend joined other cities in archiving the agency’s data on its own website.

Mayor Pete’s willingness to talk about the urgent need to act on climate seemed to resonate with folks of all ages at the Currier Museum in Manchester, people like Elise MacDonald.

MACDONALD: I would say it’s like a “top-two” issue for me – along with getting big money out of politics – which is definitely related. I’m a Gen X-er myself – so I’m not a boomer, I’m not a millennial, I’m right in the middle. But these issues have been on my mind since the first Earth Day in 1970.

DOERING: Elise was just one of the many people who lined up to meet “Mayor Pete” after his speech. College sophomore Sophia Zamboli waited excitedly with several friends.

ZAMBOLI: It’s very important to us. Actually, I’m one of the leaders of Tufts Democrats, so we are actually organizing right now an IOTF panel, which is Issues Of The Future, and this year’s panel is on Climate Change and the Green New Deal. We’re seeing the impacts daily, and it’s just something that affects our future.

DOERING: Timothy Smith, a State Representative for New Hampshire’s Manchester Ward 10, is just a couple years older than Mayor Buttigieg.

SMITH: I think it’s really positive to have someone from my generation in a national campaign. You know, the experience that people like Mayor Pete and myself grew up with is different than anyone else who’s run for president in this country before. And, bringing climate change front and center is going to be a very positive thing. I think he has a more credible case for that than a lot of the other candidates, because again, our generation and our kids are the ones who are going to have to suffer from it.

DOERING: Pete Buttigieg is quick to highlight his personal stake in the issue of climate change.

Media swarmed around Pete Buttigieg in Manchester NH April 5th as he spoke with a woman in a wheelchair. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

BUTTIGIEG: By definition, the longer you’re planning to be here, the more you have at stake in the decisions that are being made right now. It’s why I’m always talking about the need to think about the world as it will look in 2054, when I get to the current age of the current president.

DOERING: He likes to say his campaign for president is not just about the next four years – but the next forty.

[APPLAUSE]

BUTTIGIEG: And I see, in the audiences that I speak to across the country, the makings of a generational alliance. Not generational conflict – not what was experienced in the ‘60s, of young people versus their parents, but an alliance around the idea that we ought to have a better future and that everybody cares about that future, no matter your age.

DOERING: With an eye on the future and the next year and a half of campaigning for president, Pete Buttigieg is hoping that climate change and our shared need for a livable planet will be a uniting issue that helps carry him to the White House.

[MUSIC: “Freedom! ‘90”, George Michael, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 (Columbia 1990)]

DOERING: For Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering in Manchester, New Hampshire.

Related links:

- Grist | “Mayor Pete: 2020’s stealth climate candidate”

- Pete Buttigieg is one of 407 “Climate Mayors” who committed in 2017 to uphold the Paris Climate Agreement goals

- Mayor Pete’s op-ed in the South Bend Tribune about the positive impact of “Smart Streets”

- Watch: Pete Buttigieg’s April 3rd appearance at Northeastern University in Boston

- Watch: Pete Buttigieg spoke at a Concord, NH bookstore on April 6th

[MUSIC: “Freedom! ‘90”, George Michael, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 (Columbia 1990)]

Beyond the Headlines

Plastics entangled within marine vegetation that washed up on Ocean Beach in San Francisco. (Photo: Kevin Krejci, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's take a look beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with environmental health news, ehn.org. Daily climate.org. He's joining us on the line from Atlanta. Hi there, Peter, what's going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. There were two reports that came out this past week. One, a peer reviewed science report in the journal marine pollution bulletin and the other from two NGOs, on marine plastics and our waterways. The first one from marine pollution bulletin and it says that between 4.8 to 12.7 million metric tons of plastic pollution have been dumped into the world's oceans. And they tried to set a cost for the global economy from lost species, potential damage to human health and of course, losses to fisheries. Their rough guess is $2.5 trillion a year only set to go up every year.

CURWOOD: And, what about the other study?

DYKSTRA: The other study is the plastic rivers report from Earthwatch Europe, and another one from plastic oceans UK, I guess we have to get used to setting the UK and Europe apart from each other. The way that the UK is trying to do with Brexit right now. They said they gave us some good news. Plastic bags were down to only 1% of the plastic garbage in fresh water and that they think is a reflection of a long-time effort to reduce the amount of plastic bags used in grocery stores and other things. The bad news out of that is that other forms of plastic are still riding high. Plastic bottles are now number one, food wrappers are number two, and number three are cigarette butts. A little bit of good news though those plastic bags, apparently because of human Consumer Action are on the way down.

About 90 percent of cigarette filters contain plastic, and cigarette butts are often the most littered item. (Photo: Stephen Mitchell, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And I never knew cigarette butts had plastic in them. But hey, you learn something every time.

DYKSTRA: A lot of cigarettes and it’s an addictive thing. They are a negative renewable resource, I guess.

CURWOOD: Hey, what else do you have for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: It's a little three-part drama involving three charismatic megafauna species in South Africa's Kruger National Park. Kruger is famous for the wildlife that's there. They are also famous for wildlife tourism, but they also still have approaching problem there was recently a rhino poacher who was reportedly stomped to death by elephants, and then eaten by lions.

CURWOOD: That certainly does sound like a bit of charismatic megafauna karma. Is that the way to put it?

DYKSTRA: This all took place in a section of the Kruger Park called crocodile bridge. It would be even more karmic if you could get the crocodiles in on it.

CURWOOD: And how do we know this is so?

DYKSTRA: Well there were four other Rhino poachers who came out but they ended up arrested by Game Wardens. They told the tale. And this is also not without precedent. A few months ago, there was a report of three Rhino poachers that were eaten by lions at a private South African Game Reserve elsewhere in the country.

CURWOOD: Interesting and I gather to protect rhinos there they're forcing poachers to operate at night. And of course, that's when lion hunt!

A lion in Addo Elephant Park, South Africa. (Photo: Charles Sharp, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: That's when lions hunt and I guess poachers are apparently delicious.

CURWOOD: All right, time now for us to go back in history a ways. What do you see?

DYKSTRA: We're going to look at a 40th anniversary from April 19,1979. That's when the US EPA formally banned the manufacturer of polychlorinated biphenyls PCBs.

CURWOOD: Yeah, those are really nasty chemicals that are chemical cousins actually of dioxins.

DYKSTRA: They're nasty. They're carcinogens. And one of the problems is that they're extremely long lasting. Even though PCBs have not legally been made in this country for 40 years. They're used an electrical transformers, GE and other companies dump them in places like New Bedford harbor not far from you the Hudson River. There's also a huge PCB problem 40 years later, in Waukegan harbor and lake Michigan, Illinois,

CURWOOD: They not only are in the water, but then they show up in the bodies, particularly of marine mammals seem to have high levels of PCBs to this day.

DYKSTRA: They can show up in salt water in in marine mammals, and they'll show up in freshwater in sport and commercial fish, like striped bass. The Hudson River is teeming with striped bass right now; people don't catch them because you're not allowed to eat them.

CURWOOD: And what's the body burden of PCBs for humans?

DYKSTRA: PCBs continue to be long lasting and continue to show up in human tissue samples, even after the last ones were made 40 years ago. That's because PCBs are believed to last in a toxic and carcinogenic form for possibly hundreds of years.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peters’ an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website loe.org.

Related links:

- The Weather Network | “Marine Plastic Pollution Costs Up to $2.5 Trillion Per Year”

- The Sun | “Rhino Poacher Trampled to Death By Elephants Then Eaten By Lions at Kruger National Park in South Africa”

- NOAA | “What Are PCBs?”

[MUSIC: Dr. John, “Same Day Service” on Television, by Mac Rebennack (MCA Group)]

Fearsome Bull Elephant Musth

Bull elephants tend to stay on the outskirts of the herd until mating season arrives. (Photo: Courtesy of Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: As the rhino poacher in South Africa found out, a close encounter with an elephant can be deadly or at least risky as Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, also discovered.

LENDER: A herd of elephants is crossing the road. All of the adults as is usual, female. We stop at a respectful distance and turn the motor off and let the elephants pass. Branches snap. Leaves rustle and give way as they climb up into the forest on the other side. After they can no longer be seen we can still hear them. The won’t turn back but we wait, giving them time, before we start the engine.

Just then, just as we start to move, a bull elephant in full musth breaches cover.

At first the bull does not even see us.

Then he does.

And everything changes.

His head swings his eyes go wide, lock onto the offending scene and he leans first towards then away from us.

“What? WHAT!”

He does not have to say it for us to hear it.

The driver jams the stick into reverse and the little jeep pulls back fifty yards, not fast enough to antagonize him more than we have already, but fast, and keeps the engine idling.

The bull elephant comes to exactly where we stood.

As if there is a line in the dirt.

Squints.

Lowers his head.

A close-up of an African Elephant. (Photo: Courtesy of Mark Seth Lender)

The ichor of arousal runs a dark river from his temples and down his checks. Standing in the shade he himself seems not elephant grey but almost black. Glossy black. Towering, ten feet over us.

We move back again. Further this time.

Again, he comes to where we were.

Once more we pull away and finally, it is enough. He gives us a head toss, kicks a cloud of dirt in our direction, and in an attitude of body and tusks and trunk that can only be described as disdain, walks away from us in his big, swaying, slow-motion elephant walk that is faster than the fastest man on earth can run, and blunts his way into the forest toward where the object of his ardor has decamped.

Lucky for us he had something on his mind.

Other than rage.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- World Wildlife Fund | “African Elephant”

- BBC Earth | “Male Elephants in Musth Fight for Dominance”

- See more on Mark Seth Lender’s website

- Mark’s fieldwork was sponsored by Donald Young Safaris

[MUSIC: Martin Simpson, “Rosie Anderson/The Shearing’s Not for You/bogie’s Bonny Belle” on Live at the Holywell Music Room, Oxford, traditional/arr. M. Simpson (Red House Records)]

CURWOOD: Coming up – The Interior Department tries to bury a government study showing the effects of pesticides on endangered species.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Martin Simpson, “Rosie Anderson/The Shearing’s Not for You/bogie’s Bonny Belle” on Live at the Holywell Music Room, Oxford, traditional/arr. M. Simpson (Red House Records)]

Science Note: Can Plants Hear?

Researchers observed that when evening primrose was exposed to the sound of a flying bee, or similar (but synthetic) sound-signals, the flowers began to excrete sweeter nectar within three minutes. (Photo: TJ Gehling, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Just ahead, the unique mating call of the Greater Sage Grouse but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

[SFX BUZZING OF A BEE]

LYMAN: Humans can hear the gentle buzzing of a honey bee with our ears of course, but it turns out that some flowers can also hear the sound of their favorite pollinators. Well, kind of…researchers at Tel Aviv University recently found that the concentration of sugar in the nectar of evening primrose temporarily increased within minutes of sensing vibrations from pollinators’ wings. The researchers suspect the flowers act like ears, and can pick up the specific frequencies of bees’ wings, but are able to tune out background noise, like wind.

To test their hypothesis, scientists exposed plants in the lab to five sound treatments: silence, recordings of a honeybee from four inches away, and computer generated sounds in low, intermediate and high frequencies.

Plants under sound proof glass jars – the silence group – as well as plants in the intermediate and high frequency groups,

[SFX HIGH FREQUENCY SOUND FOR 1-2 SECONDS HERE]

had no significant increase in sugar concentration in their nectar.

But plants exposed to recordings of bee sounds

[BUZZING FOR 1-2 SECONDS]

and similar low-frequency sounds

[LOW FREQUENCY SOUND 1-2 SECONDS]

produced as much as 65 percent more sugar in their nectar within three minutes of exposure to the recordings.

The researchers believe that sweeter nectar may attract more pollinators and increase the chance that bee detecting evening primrose will cross-pollinate with other plants and pass on their bee hearing genes.

Evening primrose and other plants “hear” due to how their petals vibrate when sound waves pass them by. (Photo: U.S. Forest Service, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The researchers also conducted experiments that showed that the bowl-shaped flowers of the primrose picked up and amplified sound vibrations.

This single study has opened up a new field of scientific research, which the researchers call phytoacoustics.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related links:

- Smithsonian Magazine | “Flowers Sweeten Up When They Sense Bees Buzzing”

- Read the original article published in bioRxiv here

Pesticide Risks Ignored at Trump Interior Dept.

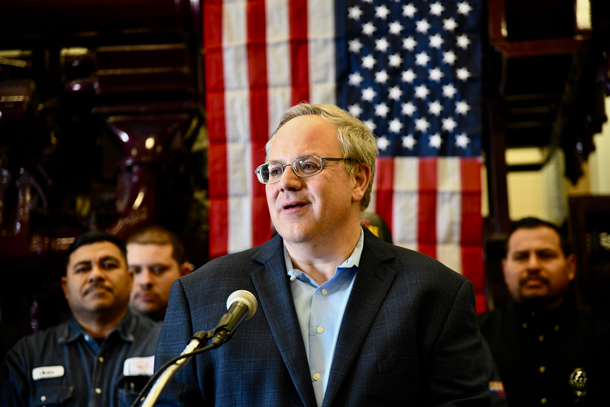

Former oil and agribusiness lobbyist and former Deputy Secretary David Bernhardt was confirmed on April 11th by the Senate with a 56-41 vote as US Secretary of the Interior. (Photo: Flickr, US Department of the Interior CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: When Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke stepped down in January amid multiple ethics probes his Deputy Secretary David Bernhardt, filled in. And now as the longtime oil and agribusiness lobbyist formally takes the reins at Interior criticism is mounting over alleged conflicts of interest. There are also complaints Mr. Bernhardt interfered with a key U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report that detailed the risks pesticides can pose to endangered species. The Center for Biological Diversity and the New York Times obtained more than 84,000 documents about the pesticide report using the Freedom of Information Act. Brett Hartl is Director of Government Affairs for the Center and questions if the public interest will be the highest priority for Mr. Bernhardt.

HARTL: Well, his track record is very much on the side of industry and special interests. And he's worked over the last, you know, 20 years or more with a pretty single-minded purpose to weaken conservation laws, to weaken protections on the ground, on public lands and for wildlife. He has been working on these issues inside and outside of governments. He was the chief political lawyer -- so the, the number three position during the George W. Bush administration -- he knows all the ins and outs of how bureaucracies work and how the federal government makes decisions and where the pressure points are and how to make things happen. This administration, we've seen a lot of very unqualified nominees, people that do not understand the job they're doing. David Bernhardt knows what he's doing, and he knows what he wants. And I think that's actually why he's so dangerous.

CURWOOD: I gather much of your concern is based on some 84,000 or more pages of documents that the Center for Biological Diversity and news organizations obtained via the Freedom of Information Act. What do those documents show to you that is of paramount concern right now?

HARTL: Sure. So, to take a step back, for about four years now, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, which is the agency responsible for protecting, conserving and recovering endangered species, has been working on, or was working on, an assessment under the Endangered Species Act called a Biological Opinion. And this Biological Opinion reviewed the impacts of three pesticides: chlorpyrifos, which is fairly well known, it's an insecticide that is thought to cause neurological developmental problems in children; and two other pesticides: malathion and diazinon. These are all what are called organophosphate insecticides, which might not mean that much, but I'll just say that the organophosphate class of pesticides was first discovered in World War II, because they have the same chemical properties as nerve agents, they actually affect the nervous system in all animals of all types. So they're very highly toxic. They've been on the shelf for many, many years. But the harm has, you know, has been suspected to be quite significant to endangered species. And career staff at the Fish and Wildlife Service worked for four years on trying to understand where those harms were happening, and to which species on the ground. And all of that work basically stopped in 2017. And it's been derailed and slowed down, and we're told sort of publicly that these reviews may be finished by 2020, or 2021. And the Freedom of Information Act documents show that when David Bernhardt was briefed by the career staff at Fish and Wildlife about this assessment, that everything changed. And these assessments basically, for all real purposes, stopped. And the most damning piece of information is that he was told that nearly 1,400 endangered plants and animals -- the United States has about 1800, 1750 total endangered species nationwide -- 1400 were being jeopardized, which is a term in the Endangered Species Act. And it means that their existence is being put at risk. So they are potentially closer to extinction as a result of these pesticides.

CURWOOD: What species are at the top of the list of concern, as far as you know?

The San Joaquin Kit Fox is highly sensitive to habitat loss and pesticides (Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC)

HARTL: Well, so that's interesting, we don't actually know because many of these documents are still being hidden, and we're trying to get them brought to light. After the New York Times story broke, there was a letter from House Democrats requesting that these documents be released to the public. Senator Wyden from Oregon asked the Inspector General, sort of the watchdog of the Department of Interior, to look into this issue. We know from the PowerPoint, the presentation that David Bernhardt received from the career staff, that the scientists were actually very worried about most endangered plants, because the vast, vast majority of endangered plants are pollinated by insects. And they are very closely tied to specific species of insects in order to be pollinated. And if these very broad, sort of non-discriminatory pesticides are being used, they could simply wipe out all of the pollinators. And if you don't have pollination, then, you know, you don't reproduce future generations. So they're very worried about listed plants. We saw in the materials that they were worried about species like the San Joaquin kit fox, which is found in California. They said that the adverse effects to the fox directly as well as from the reduction in prey and sort of small mammals would harm the species. We know the Cape Sable seaside sparrow of southern Florida; I think they said potentially 6% a year were going to be lost because of pesticide exposure. And if you only have a few hundred individuals, losing 6% a year is significant. But we don't know, we're still trying to get more of these records. You know, the Trump administration is doing their best to keep them out of the public's view. So no one really knows how dangerous these pesticides really are.

CURWOOD: We've seen a collapse of insect populations in a number of places around the world. To what extent do you think that these pesticides that you're trying to get the information about are not only endangering endangered species, but the rest of us?

The Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow is another endangered species that is highly susceptible to pesticides. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC)

HARTL: Yeah, I mean, there are, unfortunately, many, many, many pesticides that have been approved for market by the EPA over the, over the years and decades. And we have argued for a very long time that if you don't think about the impacts to endangered species, and protect sort of the most endangered things out there, what does that say about everything else? Very few pesticides have any, I would say meaningful site-based restrictions on their use. You can use most pesticides anywhere in the nation, to address any crop. Many of them are used for, you know, non-crop activities as well. So, you know, tree farms or mosquito control or whatever. But we don't really think about the large-scale impacts to sort of functioning, healthy ecosystems if you're being doused by insecticide, and then fungicides and herbicides. You know, all pesticides are basically poisons, and how they affect non-target organisms is just not considered. Unfortunately, like many of these issues, it's hard to draw the straight line of cause and effect because we live in a very complicated world, and there's many threats to species and to wildlife. But it's clear that, you know, the overuse of pesticides without real restrictions, is having big impacts out in the landscape.

CURWOOD: From your perspective, what's the motivation of David Bernhardt and the top level of the Department of Interior to block disclosure about how dangerous these pesticides may be to wildlife?

HARTL: Well, we know that a lot of the pesticide companies are, and have been, large donors to the Trump administration. So as an example, Dow Chemical, which is the maker of chlorpyrifos, gave $1 million to Donald Trump's inauguration, so back in 2017. And one of their first asks was that they wrote a letter to then-Secretary Ryan Zinke at the Interior Department, as well as Scott Pruitt at the EPA, and asked them to stop these reviews, because from industry's perspective, chlorpyrifos -- again, this is a pesticide that causes neurological developments in children -- was close to being banned by the Obama administration. Unfortunately, they ran out of time, and Scott Pruitt reversed them. But this is a pesticide that we are still using millions of pounds every year. And that's obviously a huge business profit if you're, we're using that much of this pesticide on the ground. So there's a huge financial incentive. Why does David Bernhardt want this? Well, I mean, his pattern has been since, for many, many years that he, he takes industry's side. He has worked for industry, he works for the oil and gas industry, the mining industry, agriculture, he believes sort of their perspective and he wants to help them achieve their objectives. So you know, the motivation -- sort of that classic "drain the swamp" situation that Donald Trump railed against during his campaign, but in reality, he has enabled probably more than any other modern recent president.

Brett Hartl is the Government Affairs Director with the Center for Biological Diversity. (Photo: Courtesy of Brett Hartl)

CURWOOD: Brett Harlt is Director of Government Affairs for the Center for Biological Diversity. Brett, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

HARTL: Thanks a lot. Have a great day.

CURWOOD: Mr. Bernhardt declined to respond to repeated requests from Living on Earth to appear on this program.

Related links:

- Washington Post | "Senate confirms former oil and gas lobbyist David Bernhardt as Interior secretary"

- The New York Times | “Interior Nominee Intervened to Block Report on Endangered Species”

- Documents blocked by David Bernhardt and obtained via Freedom of Information Act

- Read the Endangered Species Act

- More about the San Joaquin Kit Fox

- More about the Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow

BirdNote®: Sage Grouse Lek and Grasslands

The greater Sage Grouse performing its famous mating display. (Photo: Randy Kokesch)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: The Fish and Wildlife report concluded that pesticides can multiply the risks for species in decline. The Greater Sage Grouse is not listed as endangered but there’s just a fraction of them remaining in the wild as compared to a century ago. And as Bird Note’s Michael Stein reports, the Greater Sage Grouse is perhaps most well-known for its unique mating call and dance.

STEIN: Dawn breaks across the sagebrush country of the West on a brisk March morning.

[SAGE-GROUSE MALES PERFORMING]

Already, fifteen male Greater Sage-Grouse are strutting on their traditional display area, a sparsely vegetated arena amid the sage.

[SAGE-GROUSE MALES PERFORMING]

As the sun rises, meadowlarks begin to sing.

[WESTERN MEADOWLARK SONG]

And we can now see the Sage-Grouse clearly. The enormous males are over two feet long, and weigh six pounds. They stand bolt upright, their long tails fanned like a turkey’s tail, the dark backs and bellies contrasting sharply with their white breasts. When they display, the sage-grouse simultaneously scrape their wings back and forth against their flanks, expel air from twin, fleshy chest-sacs the size of tennis balls, and call softly. The resulting sound combines swishing, popping, and cooing.

[SOUNDS OF SAGE-GROUSE MALES PERFORMING ON LEK]

At the display area, known as a lek, the male Sage-Grouse perform for mating rights with the smaller females looking on.

[SOUNDS OF SAGE-GROUSE MALES PERFORMING ON LEK]

Female sage grouse often return to the same mate every year, leaving males without a partner, despite their flashy mating rituals. (Photo: Randy Kokesch)

As lands formerly covered in sage are converted to agriculture, so goes the fate of the magnificent Sage-Grouse. In some areas, the grouse have less than ten percent of their historical range.

[SOUNDS OF SAGE-GROUSE MALES PERFORMING ON LEK]

I’m Michael Stein.

CURWOOD: For photos of the Greater Sage Grouse strut on over to our website, LOE.ORG.

[Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

Ithaca, New York. Display sounds of the Greater Sage-Grouse recorded by G.A. Keller; call of the Western Meadowlark recorded by W.R. Fish

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2013 Tune In to Nature.org March 2013 Narrator: Michael Stein]

Related links:

- BirdNote® | “Sage-Grouse Lek and Grasslands”

- Audubon | “Greater Sage-Grouse”

[MUSIC: Hanneke Cassel, “Passing Place/Silver Special” on Trip To Walden Pond (Cassel Records)]

CURWOOD: Coming up- We’ll have more on the Greater Sage Grouse. It was once so abundant old timers remember huge flocks and routinely cooked them up. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Hanneke Cassel, “Passing Place/Silver Special” on Trip To Walden Pond (Cassel Records)]

The Sage Hen and the Sage Brush

The sage brush steppe ecosystem is vital for sage grouse leks, where the birds mate. (Photo: Susan Loredo, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Earth Day is April 22 and in honor of Earth month we are looking back at some of our favorite stories and bringing you an update. This week it’s Clay Scott’s 2002 story about the Greater Sage Grouse. For decades this showy bird has been ruffling feathers among western cattle ranchers and energy developers working in sage brush country. This landscape at first almost seems completely barren, but it’s crucial habitat for a wide variety of wildlife. Greater Sage Grouse are extremely sensitive to disturbances in their habitat and their numbers have plummeted from millions in the 1800’s to less than 200,000 today. Although the Greater Sage Grouse is not listed as endangered, a sub species identified in the year 2000 and now called the Gunnison Sage Grouse is on the endangered species list in the ‘threatened ‘category. Here is Clay Scott’s 2002 report.

SCOTT: On a cold spring morning in southwest Montana, Ben Deeble of the National Wildlife Federation is out looking for Sage Grouse. The sun is just coming up, but at 6,000 feet elevation the temperature is below freezing. Deeble walks briskly through the sagebrush. There are no obvious landmarks in this vast sea of grayish-green, but he knows exactly where he’s going. He stops and points.

DEEBLE: See where the light is hitting the high cut bank. Go to the right to the dark cut bank and there’s two cocks right below that.

SCOTT: Through my binoculars I make out two distant patches of white, the neck feathers of male sage grouse. This is their communal mating ground, called a "lek." For a two-week period in the spring the mottled brown and black males congregate at the lek before dawn. They strut, spread their fan-like tails, and rub their wings across inflated air sacs on their necks, hoping to attract females. I ask Deeble why the birds have chosen this place for their lek.

DEEBLE: This is a good spot because the sagebrush isn’t very tall, but they need to go to tall sagebrush with a lot of grass and Forbes for safe nesting. So probably the hens are nesting a mile or more from here.

[OUTSIDE AMBIENCE]

SCOTT: The wary birds flush before we get close enough to observe their mating display. They’re as big as large chickens, but surprisingly fast flyers. Deeble takes out a GPS unit, notes our position and records the number of grouse we saw. Next spring researchers will be able to return to this same spot to count the number of mating birds. Sage Grouse can have home ranges of hundreds of square miles, yet each year, like spawning steelheads, they return to the exact same spot to mate. But that extraordinary fidelity to place also makes them vulnerable to changes in their habitat, and almost everywhere the birds live that habitat is being altered, sometimes radically.

DEEBLE: What we find is everywhere in these habitats we’re disturbing them in ever-increasing tempos. For whatever reason, they’re like the canary in the coal mine, from the standpoint that they’re one of the first species that disappears as these sage steppe ecosystems become unraveled.

SCOTT: The sage steppe ecosystem is a vast, arid area of mostly public land stretching from eastern California to the western edge of the Dakotas. Healthy sage steppe includes a variety of sagebrush species, along with bunchgrasses and other plants. But much of the ecosystem is in decline along with many of the species that live in it. Sage Grouse, in particular, are dependent on old growth sagebrush. Their mating and nesting grounds have been disturbed by oil and gas drilling, coal bed methane development, the conversion of sagebrush to agriculture, and especially by the grazing of livestock.

Historic over-grazing in the sage steppe has reduced native grasses that many species depend on and led to the spread of invasive weeds that thrive in degraded soil. One recent study estimates that exotic weeds in sage country are spreading at more than 4,000 acres per day. Throughout the west the majority of grazing has been on leased federal land. Now, some environmental groups say it’s time for that practice to stop for the sake of the sage grouse and for the health of the entire ecosystem. But ranchers here say banning grazing on public land would deal a death blow to entire communities. Roger Peters is the owner of the Dragging Y Ranch. Like many ranchers, he’s suspicious of what he calls the environmental agenda.

Male greater Sage Grouse perform a dance in which they fill their two bulbous air sacs and flop their head in order to attract a mate. Female sage grouse pick from among them, and often return to the same male every year. (Photo: Bob Wick, Bureau of Land Management, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

PETERS: In Beaverhead County, Montana, we’re dependent on grazing on federal lands because that’s so much of what there is. You know, we live here. You have to use federal lands because there’s not enough deeded land to go around. So now it appears to us that Sage Grouse, they say, "Ah, Sage Grouse, we’ve got them on Sage Grouse. We’ll get them on something eventually to get their cows off the public lands."

SCOTT: Peters’ ranch is on 60,000 acres of his own land, along with several times that amount of leased federal land, much of it sage grouse habitat. He says he manages the land in an ecologically sound way and he has no patience for those who want to tell him when and where to graze his cattle. He’s especially angry at those environmental groups who think the sage grouse should be put on the endangered species list. If the bird is listed, Peters says, many western cattle operations would effectively be brought to a halt.

PETERS: Why penalize the guy that’s got the last one? He’s obviously the best caretaker of this endangered species, whatever it is. But whoever the poor guy is, the endangered species are found on his place, he’s the one whose management is penalized.

SCOTT: The advocacy group American Lands Alliance is leading the efforts to list the Sage Grouse. Mark Salvo works on sagebrush issues for the organization. He denies that his position is anti-rancher.

Ben Deeble of the National Wildlife Federation tracks the number of grouse in southwest Montana during the mating season. (Photo: Clay Scott)

SALVO: We’re not suggesting that public lands ought not be used. But we are suggesting that they have been used or abused in the past, and that changes need to be made. That’s what the plight of the Sage Grouse is showing us.

SCOTT: But not all environmental groups feel an endangered species listing is the answer, at least at this point. Groups like the National Wildlife Federation are working with state and federal agencies, as well as landowners and others, to develop management plans for Sage Grouse habitat. Ranchers are encouraged to keep their livestock away from nesting areas and to rotate their grazing to allow grass and other plants a chance to recover. Mark Salvo supports those efforts but says much more is needed. The looming threat of the Endangered Species Act, he says, is necessary to keep both ranchers and government agencies focused on the Sage Grouse issue.

SALVO: Unless that threat is there, unless we continue to push to list the species, they may back off on some of their current efforts to restore and conserve them. What my challenge is to resource users and agencies and others who don’t want to list the species on the Endangered Species Act is you probably have six to eight to ten years to reverse the declining trends for Sage Grouse and their habitat on your own.

SCOTT: Six to eight to ten years, because it will take at least that long for a final ruling on the status of the sage grouse. But some experts say that’s not nearly enough time, that much of the sage steppe is so degraded that decades will be needed to really turn things around. One federal biologist just sighed when I asked him how sage habitat might be restored. "The truth is," he said, "that we just don’t know. We can’t put it back the way it was because we don’t understand everything about how it used to be."

[SOUND OF STREAM]

SCOTT: Someone who does remember how things used to be is Bernard Harkness. In a high basin below the Continental Divide, where a snow-fed creek flows through low sagebrush, I found the retired sheep rancher standing in front of the rough log cabin he’s lived in for 77 years. He told me of a time when the birds and their habitat were in better shape.

HARKNESS: They would come in here right around the first of July, just thousands and thousands of them. I’ve seen them flying-- I don’t know how many you’d see, hundreds of thousands. It’s a big, open grassland, and wide; oh, five, six, seven miles. You can see in any direction that’s open there. As far as you could see, there would be sage grouse walking, eight to ten feet apart.

SCOTT: Harkness dug out a yellowed copy of The Lima Ledger from 1935 and pointed to an article titled "Hunters Bag Ton of Sage Hens." The headline was meant literally. In this basin alone, hunters killed 10,000 birds in a three-day season.

Bernard Harkness remembers when hundreds of thousands of sage grouse lingered in the grasslands near his cabin. (Photo: Clay Scott)

HARKNESS: If you wanted a Sage Grouse dinner then you’d just walk out with a .22; get three or four. You fried them, fried the breast. And then the others, the backs and the legs and the giblets, you’d make a gravy just like turkey gravy or something, and on the potatoes, and that was a pretty good meal.

SCOTT: As I was leaving, Bernard Harkness reminisced about the spring mating display of the sage grouse. "Before I die," he told me, "I’d sure like to see the birds do that dance again."

CURWOOD: That’s reporter Clay Scott in Montana back in 2002, and you can visit our website loe.org to hear more of that story. Clay did eventually get to see the birds do that dance. There weren’t thousands of them as Mr. Harkness remembered, just 5 males at a clearing calling and dancing for all they were worth to attract a female.

Related links:

- National Wildlife Federation | “Saving the Greater Sage Grouse”

- National Wildlife Federation | “Greater Sage-Grouse”

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service | “Greater Sage-Grouse”

Greater Peril for the Greater Sage Grouse

Greater Sage Grouse Lek in Colorado. (Photo: Julio Molero, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In a moment we’ll have an update on the plight of the Greater Sage Grouse with Collin O’Mara, he’s the president and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation. But first here is a recent recording of the Greater Sage Grouse mating call, courtesy of the Macauley Library Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

[SAGE GROUSE SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: What are we listening to here, Collin O'Mara?

O'MARA: So Steve, you just heard the amazing mating ritual of the Greater Sage Grouse. And so now just for all your listeners, imagine a about a two-foot bird that's you know, pretty flabby, pretty chunky, hopping around with these massive tail feathers that are big and spiky and kind of backing the entire bird as well as two huge yellow bulbous air sacs bulging out of their neck trying to attract the females in their lack to make sure that they are kind of the best mating partner that they possibly can be.

CURWOOD: So that's a hard way to pick up chicks, isn't it?

O'MARA: I'll tell you one thing I mean, with given some of the dance moves we've seen over previous generations, I'll put the Sage Grouse moves against any human any human move, in the last several decades.

CURWOOD: The Sage Grouse is considered by some naturalists as a indicator species. Why is that?

O'MARA: So if you look at the sagebrush steppe, habitat that kind of spans parts of 11 states across the West, there's about 350 different species that depend on this habitat type and they're species that range from things like mule deer, pronghorn, and there's a range of other species, as I said, 350 in total. And if the sage grouse is doing well, because the habitat is strong, and because they can kind of support their survival on their population growth, then that means the habitats of sufficient quality to support the other 350 species that depend on the same land.

CURWOOD: Now, go back in history a bit we used to have how many sage grouse in North America? And what do we have today?

O'MARA: Yeah, the numbers have dropped precipitously. Historically, the number has been well over a million birds, some estimates goes as high 16 million birds were on the landscape. And most recent estimates have it, you know, one to 200,000. Some have it a little higher than that. But that's the general again, so at least a 90, you know, 95% decline in the in the previous few decades.

CURWOOD: What was the setup under the Obama administration to protect the Sage Grouse?

O'MARA: Yeah, starting with the leadership of President Obama and Secretary Ken Salazar, who is running the department interior and the first Obama term, there is a huge collaborative effort put together with Republican and Democratic governors across the West to really try to identify those measures that would be most effective at recovering the Sage Grouse. And they included a range of activities. So for example, one was reducing mining activities for coal mining. And some of the most important habitat areas and another was making sure that oil and gas developments that were proposed in various areas were limited to those areas, that we're not directly going to impact the Sage Grouse. There's also a series of measures that were required that if you did have impacts in the habitat you had to mitigate what those are doing, kind of restoration projects elsewhere to try to make sure that the overall population health would benefit from additional kind of habitat availability.

Two male sage grouse compete for female attention. (Photo: Rick McEwan, Sage Grouse Initiative))

CURWOOD: The new administration has walked some of that back, they're going to allow more activities there. What would be the impact of having the oil drilling that the Trump administration has authorized in this area? Oil and gas drilling?

O'MARA: Yeah, so the Trump administration has, has proposed basically not differentiating between kind of drilling in areas that are important to the Sage Grouse and areas that are not as important to the Sage Grouse. And, you know, anytime you have kind of habitat disturbances on the landscape, they can affect, you know, this, this bird that's very sensitive to habitat changes that mean, the sage brush that they depend on for kind of habitat value, takes a long time to actually establish itself and to, and to grow. And so if you're running pipelines, if you're putting in well pads, if you're doing the things that kind of modern oil exploration can do, and you're doing it in areas that are directly kind of critical to the survival of the specie, obviously, you can, you can really alter their long-term chances. And these leks these and kind of important habitat areas over some of the areas that we were trying to say should be off limits. And all the governors agreed, I mean, Republicans and Democrats from across the West agree that these places should not be places where there's drilling activity yet the Trump administration removed the protections that would have prevented that from happening.

CURWOOD: So what's the scientific basis of the Trump administration's decisions to allow oil and gas drilling and cattle grazing?

O'MARA: I don't think there is a strong scientific underpinning, I think that there were some specific industry groups and others that wanted to see some changes for financial reasons, there was some science to basically show that you do have to kind of mitigate these impacts, given the kind of the population densities that we're trying to achieve. But I think they're extremely vulnerable on the scientific side, because this is more of a political process, where they're asking people kind of what changes they wanted to see, as opposed to talking to the leading scientists. Almost all of them said, “no”, we need to keep the plans in place. And if anything, we should be talking about strengthening the plans, not taking a step backwards. And you have world class biologists from across the West, united on this, that there really is no scientific basis that could allow this kind of activity and then also see the birds recover.

CURWOOD: How fair is it to say Collin that the Trump administration's approach to this is the heck with the environmental advocates in the species protectionists we need these fossil fuels, we need to feed our cows?

O'MARA: There was an executive order that President Trump signed in his first year that he kind of this this so-called Energy Dominance, executive order. And it basically said that we are going to remove every barrier we possibly can to any kind of oil and gas development. And what we're seeing is that there's just no, there's no balance, right? There's no attempt to try to protect, you know, important wildlife habitat. There's been a little bit of an effort around some of the migration corridors for some of the bigger game species in particular things like mule deer and pronghorn and elk. But for the most part, we're seeing that we see 95 million acres, for example, across the entire country opened up for oil and gas drilling auctioned off last few years, we've seen less than 30,000 acres proposed for kind of conservation protection. That's a massive difference. And, you know, at a time when oil prices are low, and you know, we if anything, we should be switching to alternative fuels and reducing our overall emissions given the kind of escalation of the climate crisis. You know, this is going in exactly the wrong direction, when what we really need in this country is balance. And that's what the department of interior is supposed to be doing. We're just not seeing much of it right now.

CURWOOD: So if the Trump administration began with a policy of full speed ahead for energy extraction from public lands, what would be the impact of the reelection of Donald Trump as president?

O'MARA: I think this is the one of the most important questions I mean, I think they're, you know, we can look at polling in the West, an overwhelming number of kind of folks that live in places like Colorado, Montana and Wyoming and Idaho and Utah believe that the energy dominant strategy has gone too far. They oppose the reductions of the national monuments at Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante. They think that the public input that's been reduced should go back up you know, folks should have more input into these decisions. But at the same time, and I think, you know, when energy prices are low, and unemployment, is low, folks traditionally have had high probabilities of getting reelected. And so I think we're trying to make the case that conservation is a, you know, it's an American value this isn't a Democratic or a Republican issue it affects everybody. And if we allow these species to go extinct if we lose access to these amazing public lands that really differentiate us from the rest of the world, that we're losing something that we simply can't get back. And that at a time when one third of all wildlife species in this country are at heightened risk of extinction in the coming decades, at a time when our outdoor economy is an $887 billion juggernaut that's employing people in every county across the country, that having this short sighted focus on energy extraction at all costs, is coming at the detriment of not only our wildlife and natural heritage, but it's coming at the detriment of one of the most explosively growing parts of our economy related outdoor recreation. And so if the question becomes who's going to do more for you know, American jobs now we hope that the voices of outdoor recreation and kind of our natural assets are given the full attention of the electorate and not just you know what the prices at the pump.

CURWOOD: Collin O’Mara is the president and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation.

Related links:

- National Wildlife Federation | “Saving the Greater Sage Grouse”

- Audubon | “Zinke’s New Sage Grouse Plan Will Hurt, Not Help, Sage Grouse Recovery Efforts”

- The New York Times | “Trump Administration Loosens Sage Grouse Pretections, Benefiting Oil Companies”

- National Geographic | “A Running List of How President Trump is Changing Environmental Policy”

- Defenders of Wildlife | “Basic Facts About Sage Grouse”

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service | “The Sage-steppe Ecosystem”

[MUSIC: Bireli Lagrene, “Place du Tertre” on The Rough Guide To the Music Of Paris (originally on Move), (Rough Guide/World Music Network)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Delilah Bethel, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth