January 24, 2020

Air Date: January 24, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Appeals Court Reluctantly Dismisses Youth Climate Case

View the page for this story

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit recently dismissed the Juliana v. United States case, in which youth sought to hold the federal government accountable for not doing enough to address climate change. Pat Parenteau of the Vermont Law School joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the tough decision the judges faced and what could be next for the youth climate case which has already been before the US Supreme Court twice on procedural matters. (09:29)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DyksraView the page for this story

In this week’s Beyond the Headlines segment, Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb look at the European Union’s plan to become carbon neutral by 2050. Next, they turn to internet dating profiles and how users are matched based on their concern about climate change. Finally, in the history calendar, they look back ten years at the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision to roll back some restrictions on campaign financing. (04:27)

A Plan to Avoid Extinctions

View the page for this story

A recent United Nations biodiversity report comes to the sobering conclusion that as many as 1 million species are at risk of going extinct in the coming decades. In response the UN Convention on Biodiversity has released a new plan to avert the crisis. Tierra Curry from the Center for Biological Diversity joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the biodiversity crisis and plans to address it. (11:41)

Mangroves Thriving in a Warming World

/ Brendan RiversView the page for this story

Rising temperatures are enabling mangroves, resilient trees that grow in saltwater, to expand their range in Florida and beyond. Brendan Rivers of WJCT in Jacksonville reports. (03:21)

BirdNote®: Laysan Albatrosses Nest at Midway Atoll

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Many of us may feel like hibernating through the winter, but for the Laysan Albatross, this is the perfect time to get to work on nesting and raising chicks. BirdNote®'s Mary McCann has more. (01:57)

Norway’s Disappearing Winter

View the page for this story

Scandinavia is nearly synonymous with cold and snow, but a recent study from Norway shows that’s beginning to change. Reidun Skaland, a climate scientist from Norway’s Meteorological Institute, speaks with Host Bobby Bascomb on Norway’s lost winter days. (04:10)

Redlining Linked with Extreme Urban Heat

View the page for this story

In the 1930s, while the world was digging out of the Great Depression, the US government came up with a plan to rate neighborhoods based on their presumed suitability to receive home loans. The neighborhoods that the government, and banks, considered riskiest were outlined in red. These “redlined” neighborhoods tended to be in city centers and home to black Americans. Today as climate change exacerbates urban heat, they’re experiencing much higher temperatures than surrounding areas. Vivek Shandas is a lead author of the research and speaks with Host Bobby Bascomb about the unequal impacts of racist ‘redlining’ practices. (10:56)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Tierra Curry, Pat Parenteau, Vivek Shandas, Reidun Skaland

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Brendan Rivers, Mary McCann

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The UN has an ambitious plan to reverse the trend of species extinction.

CURRY: If we can get people to realize there is a problem I think people around the globe will put pressure on their governments to step up wildlife protection especially as things get so bad that everybody notices. I think almost everyone’s noticing when’s the last time you saw a firefly? When’s the last time you saw a monarch butterfly? When’s the last time you saw a bat?

BASCOMB: Also, mangrove forests are more effective than rainforests at sucking up excess carbon and they are expanding their range in parts of Florida.

GESELBRACHT: 25% of Florida’s greenhouse gas emissions may be reduced by the amount of mangrove expansion over the next decade or two into northern Florida and even beyond.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Appeals Court Reluctantly Dismisses Youth Climate Case

Youth plaintiff Levi Draheim rides on the shoulders of a supporter as he makes his way to a rally following a hearing in the Juliana v. United States climate change lawsuit. (Photo: Robin Loznak/Our Children’s Trust)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in for Steve Curwood.

Some 3000 of the world’s most powerful corporate executives and government leaders recently gathered in Davos, Switzerland for a meeting of the World Economic Forum. The yearly event is an opportunity for this influential group to discuss their vision of an ideal future and the dangers that face the world at large. High on the agenda was climate change, which President Trump downplayed as a threat.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: To embrace the possibilities of tomorrow we must reject the perennial prophets of doom and their predictions of the apocalypse. These alarmists always demand the same thing, absolute power to dominate, transform and control every aspect of our lives.

BASCOMB: The elite participants at Davos were joined by climate activist Greta Thunberg, who spoke pointedly about the perils of turning a blind eye to climate change.

THUNBERG: I wonder what will you tell your children was the reason to fail and leave them facing a climate chaos that you knowingly brought upon them. Our house is still on fire. Your inaction is fueling the flames by the hour. And we are telling you to act as if you love your children, above all else.

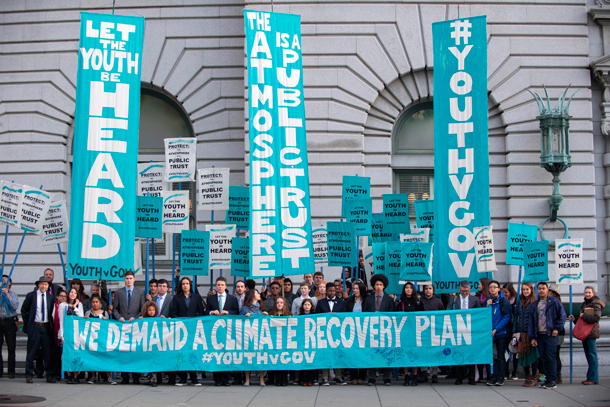

The Juliana v. United States youth plaintiffs cheer outside the federal courthouse in Eugene, Oregon after a hearing in district court. (Photo: Robin Loznak/Our Children’s Trust)

BASCOMB: Thunberg is one of many young climate activists speaking out to demand systemic change. For five years, the groundbreaking youth climate change case known as Juliana v. United States has been working its way through the courts. The 21 youth plaintiffs in the case argue that the federal government has failed to address climate change, which threatens their right to a livable planet. Now, before even going to trial, the case has reached what may be the end of the road. The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit decided, 2 to 1, to dismiss the case. Our legal expert Pat Parenteau of the Vermont Law School has been following Juliana VS the US since the beginning and joins us now from White River Junction, Vermont. Pat, good to have you back on Living on Earth!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Bobby, good to be here.

BASCOMB: What reasons did the US Circuit Court of Appeals give for dismissing the Juliana case here?

PARENTEAU: Well, they basically considered this case a political question. And there is a doctrine, of course, in constitutional law, that the federal courts should not involve themselves in political questions that raise major policy issues that have to be decided by the other two branches of government, namely Congress and the executive branch. So this was a "reluctant" decision, as the court, the majority judges on the panel said. And they said, despite the compelling case that the plaintiffs had made about the dangers of climate change and the catastrophe that is looming, the courts are just not the place to go for broad-scale relief, and two members of the three-member panel just didn't see a way forward. They were worried that even if they ordered the government to produce a plan to address climate change, that they wouldn't be able to enforce the plan through the traditional mechanisms of injunctions and other things that courts do. I happen to think they're wrong about that. But that's what they decided.

BASCOMB: And why do you think they're wrong?

Youth plaintiff Kelsey Cascadia Rose Juliana high-fives supporters. (Photo: Robin Loznak/Our Children’s Trust)

PARENTEAU: Well, in part because they jumped the gun. This case was really about whether there should be a trial, and whether or not evidence should be heard. I mean, it has echoes of what's happening right now with impeachment, frankly. And usually what happens in cases is you have a lot of evidence and testimony about what kind of remedy would be appropriate to address, in this case, a constitutional violation. The underlying claim here is that the youth are entitled to a climate system capable of sustaining life on Earth, very fundamental claim. And the Ninth Circuit panel recognized the validity of that claim, acknowledged that was a valid claim to make, and a serious one. So if that's true, then you should have a trial on what kinds of remedies might be appropriate. It may not be everything the plaintiffs were asking for, which was a date certain by which we'd be at zero carbon. But it could have been a series of incremental steps, where the government gradually began to withdraw support for fossil fuels, and increase support for non fossil fuels and take a whole number of other actions: managing public lands better, not investing in offshore drilling, and so forth. So the problem with making a decision at this juncture is you don't have a full record of all the possibilities that the court might use to decide what to order the government to do or not do.

BASCOMB: And all three judges in this case were appointed by President Obama. How likely is it that this court was the best chance that these plaintiffs would have for a ruling in their favor, or at least proceeding to trial, as we talked about?

Plaintiffs in the Juliana v. United States case outside of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. (Photo: Robin Loznak/Our Children’s Trust)

PARENTEAU: I think this was the best possible panel they could have drawn, and it was clear how sympathetic that judges were. Their heart was telling them they needed to do something to help the situation and address the legitimate claims the plaintiffs were making, and recognize that these youth plaintiffs had no power to prevent the harm that's coming. The Ninth Circuit panel talked about the fact that we're approaching a point of no return. The dissenting judge, Judge Staton, mentioned that it's like a asteroid hurtling at the earth, and the United States government has decided to take down its defensive mechanisms. So, they're, highly charged language in this opinion, about the nature of the danger that we're facing, in contrast to the ultimate resolution, which was the court throwing up its hands and saying, but there's nothing that we can really do about it. Pretty sad day, frankly, for, in my view, for the judiciary.

BASCOMB: Now, I understand the nonprofit Our Children's Trust, which is backing the Juliana plaintiffs, they've vowed to appeal the case to the full court. Does that mean this isn't necessarily dead?

Lead plaintiff Kelsey Cascadia Rose Juliana is now 23 years old and vows to continue to petition the courts for a trial. (Photo: Robin Loznak/Our Children’s Trust)

PARENTEAU: It's not necessarily dead, and Our Children's Trust is on a mission, they're not going to probably yield willingly. Here's the problem with asking the full Ninth Circuit to review it. You have to have a majority of what, they're called the active judges on the court, to get a full court review. There are 29 judges on the Ninth Circuit. 10 of the judges on the Ninth Circuit have been appointed by President Trump, three of them by President Bush; there's very little chance that you could get a majority of the other judges on the Ninth Circuit to agree to rehear this. And even if they did agree to rehear it, it's very unlikely you would get a more favorable decision than the one that the panel has already rendered. And then the real question is, if that doesn't work, will they file a petition for review by the Supreme Court, and it looks as if they probably will do that as well. And the problem there is, is lawyers have to step back and think about the longer term interests of their clients in making a move like that. There's, there's a danger of letting your ego get in the way of your judgment. And they know they're right, in some sort of cosmic sense. And in terms of moral rectitude, they're right. What they're saying is absolutely right, and the courts should be responding. But you also have to take account of the reality that you do not have a Supreme Court that's open to this kind of very aggressive judicial intervention, so that you have to take account of the risks you're running of making really bad law in the pursuit of the good. And I don't envy the lawyers having to make this decision, but I trust them enough to think carefully before they take that step because it could have real long-term consequences.

BASCOMB: Well, now that the case has been dismissed, what if anything do you think has been accomplished in the course of this?

Former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau teaches environmental law at Vermont Law School (Photo: courtesy of Vermont Law School)

PARENTEAU: Oh, I think a lot has been accomplished. They've brought so much attention to bear on this problem. They've exposed the government, not just the current government but going back five different administrations and documented in detail all of the failures of the US government to address this problem, all of the opportunities that have been lost, and yet how much opportunity still remains. So just from the standpoint of building an historic record of this moment in time, the case has done an enormous amount. It's galvanized the youth movement around the world. It definitely had an impact on people like Greta Thunberg, and that whole coterie of the Sunrise Movement and the Extinction Rebellion and all of that wonderful energy that's coming out of the youth and the millennials at this point. It's inspired cases in other parts of the world. It inspired the case in Colombia, where the Colombian Supreme Court ordered the government to stop deforesting the Amazon basin because of the climate impacts and impacts on biodiversity and so on. And there are cases being brought even as we speak, in other countries in the world where the courts may be more open to intervening and doing something positive. So I think Our Children's Trust, the youth plaintiffs, the lawyers, have done a tremendous public service with this case. And it's going to echo down through the years. I'm sure of that. So, it's hard to do it, but I think you have to recognize you have accomplished a lot, and now it's time to turn the page and move on.

BASCOMB: Pat Parenteau is a professor at Vermont Law School. Pat, thanks again for taking the time with us today.

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Bobby. Always a pleasure.

Related links:

- Read the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit’s full opinion on the Juliana case

- The Our Children’s Trust website

- Vox | “21 kids sued the government over climate change. A federal court dismissed the case.”

- About Professor Pat Parenteau

[MUSIC: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, “Teach Your Children,” by Graham Nash, Atlantic Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Poland relies on coal for much of its energy production. (Photo: Hans Permana, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: It's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and daily climate.org. Hey there Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby, let's start with the very encouraging news from the European Union. They've laid out a commitment for a trillion dollars in financing from the European Investment Bank and direct investment of about 100 billion to make the whole EU economic bloc carbon neutral by the year 2050.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's a big price tag and a big goal. But how did they get countries that are heavily dependent on coal like Poland on board?

DYKSTRA: There's the little catch. They didn't get Poland on board. They gave them a pass because Poland is so coal reliant. There were a few other Eastern European countries like Hungary and the Czech Republic that went along with this plan reluctantly, but other than that, Poland is exed this plan and of course the UK is exed out of the European Union entirely.

BASCOMB: Mhm, right. Well, that's certainly something to keep an eye on. It's an ambitious goal anyway. What else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, here's a, here's a weird one that, but it may be a sign that climate concern is hitting the mainstream. There's a dating site called OkCupid that filters out potential dating matches, partly by asking questions about politics. So for example, you don't have a hardcore Trump supporter that gets paired up with a hardcore Trump resistor.

Some dating apps filter out potential dating matches, partly by asking questions about politics and now, climate change. (Photo: Abaicus, Flickr, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Hmm, that makes sense. Well, how did you come across this tidbit of information though? Are you online dating yourself?

DYKSTRA: Uh, no, I'm not. And at my age, it's more like carbon dating. But there are several websites that reported on this including, there's a great new newsletter from a journalist named Emily Atkins. It's called Heated.World. They've mentioned the OkCupid site and its potential to show through that site's own polling that its own users are deeply concerned about climate action.

BASCOMB: Hm. Yeah. I'd be curious to know how many of their users say 'no climate change isn't real, not a problem.' I mean, it's relatively young people usually using these sites.

DYKSTRA: It's all part of making America date again.

BASCOMB: Oh, boy, you had to.

DYKSTRA: Sorry.

BASCOMB: Well, what do you have for us from the history vaults this week?

DYKSTRA: The 10th anniversary of the Citizens United Supreme Court decision, one of the most momentous Supreme Court actions, really in our lifetimes. On January 21, 2010, the court voted five to four in favor of rolling back some restrictions on campaign financing, specifically large outside donors, particularly to ad campaigns, critical candidates, kind of enriches the TV stations who get the money and the political consultants who put the ads together, and I think creates a little bit of intellectual poverty among voters. What this decision does is it makes it much harder to put the reins on so called independent expenditures. and dark money in political campaigns, not just on the national level, but on the statehouse level as well.

Signs from Atlanta’s “Money Out, Voters In” rally. (Photo: United for the People Georgia, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Mhm. And how has all of that dark money and politics affected the environment and the way politicians are choosing to support or not support environmental issues?

DYKSTRA: Well, one of the things that's happened since Citizens United is that whatever Republican concern there was among office holders about climate change has absolutely vanished. If you go back to a little bit more than 10 years ago, Mitt Romney was in favor of climate action. The late John McCain was in favor of climate action. And governor Sarah Palin of Alaska, actually had a climate sub-cabinet to address the concerns in the sub-Arctic. All of those people changed, others changed. And the political climate on climate change is more polarized than it's ever been.

BASCOMB: Mhm. So you're saying then that Republicans feel like they can't take on the issue of climate change because they're going to have all this dark money put against them if they do, from what the like of the Koch brothers and such.

DYKSTRA: Right, and the more moderate candidates are afraid of getting challenged in primaries by candidates backed by this dark money, who for the most part, are in the camp of climate denial.

BASCOMB: Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Thanks, Peter. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on the stories on our website loe.org.

Related links:

- Read more on the European Union’s plan to become carbon neutral by 2050

- BBC | "EU carbon neutrality: Leaders agree 2050 target without Poland"

- Earther | "Caring About Climate Can Help You Get Laid"

- Climate journalist Emily Atkin's newsletter, HEATED

- The Center for Public Integrity on "The 'Citizens United' Decision And Why It Matters"

[MUSIC: Edgar Meyer/Chris Thile/Stuart Duncan/Yo-Yo Ma, “Qurter Chicken Dark” on Goat Rodeo, by Edgar Meyer, Stuart Duncan, Chris Thile, Sony Music Entertainment]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Most birds migrate for winter or stay put and wait for spring but for at least one large sea bird winter is a time of year for nesting and raising chicks.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Edgar Meyer/Chris Thile/Stuart Duncan/Yo-Yo Ma, “Qurter Chicken Dark” on Goat Rodeo, by Edgar Meyer, Stuart Duncan, Chris Thile, Sony Music Entertainment]

A Plan to Avoid Extinctions

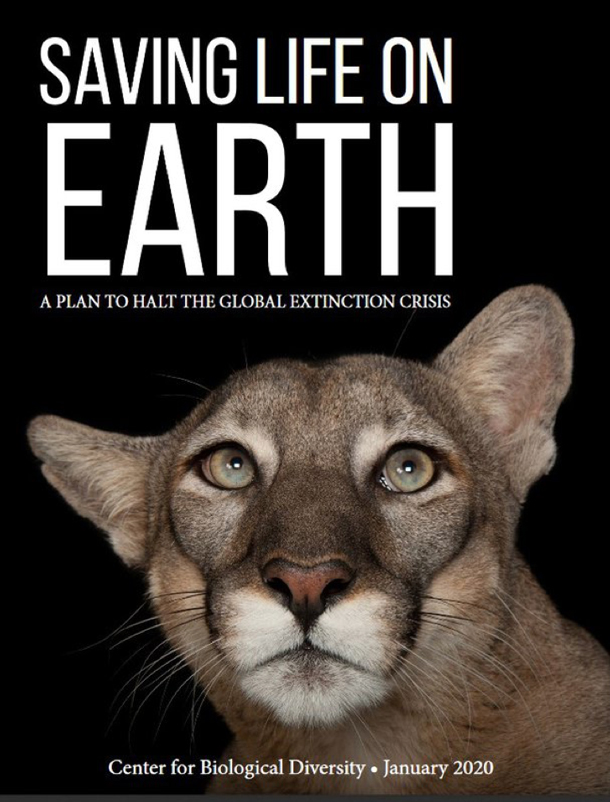

The Center for Biological Diversity is calling for expanded public lands and additional protection for endangered species (Photo: Courtesy of the Center for Biological Diversity)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb. A recent United Nations Biodiversity report comes to the sobering conclusion that as many as 1 million species are at risk of going extinct in the coming decades, as we witness the 6th mass extinction on planet earth. The report found that humans are responsible for extinction rates that are up to 1000 times greater than what would be expected without us. As species disappear before our eyes the United Nations and the Center for Biological Diversity have released plans which address both the extinction crisis and climate change. For more, I’m joined now by Tierra Curry. She’s is a Senior Scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity. Tierra, welcome back to Living on Earth.

CURRY: Thanks so much Bobby. I'm always happy to be here.

BASCOMB: Oh, we're always so happy to have you. So this UN report says that we're in the midst of the sixth mass extinction that the earth has experienced, the first one caused by humans. Can you give me some examples of animals that are staring down at extinction in the coming decades?

CURRY: Basically, all groups are at risk now, birds, insects, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, coral reefs, there isn't a single taxa that isn't at risk from this extinction crisis. Even common species, vertebrate populations are plummeting around the globe, we've killed off like more than half of all vertebrate populations in the last 40 years and insect scientists estimate that between 10 and 40% of insect species are at risk of extinction. And here in North America, the most imperiled group of organisms is freshwater mollusk, we've already lost more than 70 freshwater snails to extinction, and more than 25 freshwater mussels and 70% of the remaining ones are at risk. But across the globe. There's so many issues now; Exploitation, I mean, we could lose elephants in a couple generations, there is a beautiful little porpoise in the Gulf of California called the Vaquita, and it's like a tiny dolphin, and there's less than 10 of them left. And so across the globe, there's species people have never heard of, and species that are gorgeous, and that everybody loves, like elephants and giraffes and vaquitas that are at risk of extinction.

Amphibian species such as this Northern Leopard Frog are sensitive to habitat destruction and toxic chemicals in freshwater systems (Photo: Isaac Merson)

BASCOMB: Now, I understand that a lot of the extinctions are happening in the ocean, and it's largely going unseen, because you know, people don't live there so much. Can you tell me a bit more about the things there that are concerning you?

CURRY: Sure. So the ocean has done humanity a really big favor in that it has absorbed a ton of carbon dioxide, which is good for us, but it has caused the ocean to acidify. So here in Oregon, where I live, baby oysters are having trouble growing shells because the ocean has become so acidic and coral reefs which support so much of marine life, so many different species of marine life have some part of their life cycle on coral reefs, are at risk so much so that some scientists estimate that we can lose all of them if we don't get a handle on ocean acidification. And then there's just overfishing. A very small percentage of all species are harvested sustainably. So that's still a big problem that all countries need to address. And then there's plastic, which causes trouble everywhere. Even if it's intended to be recycled, a lot of it ends up in the ocean. And then sea turtles and sea birds eat it, which is terrible. And oh my gosh, this list could go on for way too long. But then there's rising sea level, which is going to inundate coastal marshes, which also support a lot of species that are very important.

African Elephants greeting one another in northern Tanzania. Elephants face severe threats of exploitation from the ivory trade. (Photo: Isaac Merson)

BASCOMB: Gosh, the list does go on. Well, let's talk a bit about what the UN is proposing to address this problem. They're planning to bring it up in China in October this year, what are the goals of the UN plan?

CURRY: So the overall gist of the plan is no more net loss of habitat, marine or terrestrial, by 2030. And then to set aside half of the earth as protected by 2050. Right now, only 15% of land is protected and only 6% of the oceans are protected. So, scientists kind of agree that if we can get 30% protected by 2030 and 50%, by 2050, we'll have a chance at surviving

BASCOMB: A chance. That doesn't sound too encouraging.

CURRY: I mean you got to start swinging your hammer somewhere.

BASCOMB: Well, I mean, 50% of the of the land by 2050. Sounds ambitious, how likely is it that that's going to actually get anywhere? I understand back in 2010, there was a similar goal established by the UN and that didn't really get too far either. What is the real hope of this being accomplished?

CURRY: Well, the goal of the previous goals haven't been met. And that's why I think that by 2030, they're calling for no net loss, that we at least stabilize the baseline where we are now and I think that it's really going to take a ground shift of people, not just you know, carrying their own water bottle and changing their light bulb but really putting pressure on their governments to protect wildlife because wildlife are so important not just for the ecosystem services they provide, like cleaning the water, stabilizing the soil, pollinating your crops. But wildlife are part of who we are, they're part of our stories, our language or culture, almost everyone loves wildlife. And so, we need to protect it for ecosystem services, but also for our own well being. And if we can get people to connect to that and to realize there is a problem, I think people around the globe will put pressure on their governments to step up wildlife protection, especially as things get so bad that everybody notices. Like, I think almost everybody's noticing. When's the last time you saw a Firefly? When's the last time you saw a monarch butterfly? When's the last time you saw a bat? Like, last summer when I went out night after night, I bought this bat detector that tells you you just plug it into your iPhone and it tells you what species of bat you're hearing. And I was so excited about it. And I went out like 10 nights and I didn't see a single bat and my heart was just crushed out. And I think that that's becoming a more common experience. And we don't want to be the generation that lets the monarch butterfly go extinct. We don't want to be the generation that lets swamps become empty of frogs, like kids have the right to hear those frogs singing and to chase monarch butterflies. But I think as more people become aware of these things, they're going to be like, Yes, I want I want to see a frog. I want my kid to see a frog. I grew up with these things. I haven't seen a frog in forever.

Common and iconic species like the Monarch Butterfly are facing severe population crashes. (Photo: Isaac Merson)

BASCOMB: Well, that's the thing I think that's so shocking about it is that in one lifetime, and you're not that old, and you remember when there were bats, and now there aren't bats. I mean, it's just so fast, the pace at which things are disappearing.

CURRY: It is fast. And I mean, the good news is, for the most part, we know what's causing a lot of these things: habitat destruction, exploitation, pesticides, the revolving door between the pesticide companies and the Environmental Protection Agency. So once we identify what's causing a problem, if we can put enough pressure on our governments then then we can address that. And so I am hopeful. I know how bad things are because I think about extinction every day, like it's literally my job to follow extinction. And but that also causes me to think about how can I get more people on board? How can we effectively pressure the government? We've got this plan, we're going to follow all of the presidential candidates around in a polar bear costume, and try to get them to take a position on the extinction crisis.

BASCOMB: Now I understand your organization, the Center for Biological Diversity has released your own plan in addition to the polar bear plan, but it's called Saving Life on Earth. Can you tell me about that? What are you calling for?

Many species such as bats and insect-feeding birds are struggling to survive in altered landscapes (Photo: ErinAdventure on Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURRY: We want the US government to declare the extinction crisis, a national emergency, because that would allocate resources to address it and it would also raise awareness and get more people involved. Here in the US we're pushing for the quote unquote, protected lands now that are used for other purposes to get actual protections, which right now under the multi-use mandate, public lands that are allegedly protected are used for fossil fuel drilling, for logging, for grazing and we want the United States government to prioritize biodiversity protection and carbon sequestration and recreation on those protected areas and to protect even more areas. We want the Endangered Species Act to be restored to its full strength and all of the imperiled species that aren't yet protected to be protected, and we want imperiled species to get protected before they crash.

BASCOMB: Mm-hmm.

CURRY: We're calling for the Environmental Protection Agency to adopt the precautionary principle and to adequately protect us from pesticides and other toxics, to move away from plastic entirely, to move towards plant-based plastics and to recycle all plastics so that more plastic isn't entering the ocean. And in our freshwater right now, plastic pollution is dumped into rivers and streams. And that's ridiculous. So there's things like that that just have to stop. And then we're calling for the designation and protection of more wildlife corridors and at least 1000 more wildlife underpasses and overpasses so that populations can be connected and can migrate. And these are actually already happening in a lot of places like outside Seattle on Interstate 90 the Snoqualmie Pass they've built these amazing wildlife underpasses and overpasses that are vegetated and they are tall enough that elk and bear are moving through them. But they're also building habitat for smaller species like amphibians and snakes, which is amazing. So those are things that states can help with that communities can wrap their minds around, like how do we create an overpass in my community? How do we get this park to go pesticide free, like everyone can get involved in this at some level, we have to address this extinction crisis because not just the wellbeing of wildlife depends on it. But our well being depends on our actually protecting the planet. It's kind of like back in the 70s when rivers were catching on fire, and the Clean Water Act was passed. We're kind of at that pivotal moment again. Things are really bad and we really have to take national level action all the way down to local action and individual lifestyle action to protect them.

BASCOMB: Well, climate change and biodiversity loss are two, just huge problems and very distinct, but they're also very related and interconnected. Can you talk a bit about that? How is climate change affecting the loss of biodiversity and the loss of biodiversity may be exacerbating climate change?

Widespread pesticide use, habitat loss, and climate change are some of the most significant drivers of the decline of flying insect populations. (Photo: Isaac Merson)

CURRY: For sure. You know, for 12 years now, I've been trying to get protection for endangered species. And when I started this job, I actually worked on some species that climate change wasn't identified as the primary threat for. It was like old fashioned threats like logging and mines. And now I can't even think of a species that isn't threatened by climate change. That's how bad that problem has become. But by protecting species, we can, and the habitat they need. We can also address climate change. Like, the Northern Spotted Owl in the Pacific Northwest, when it was protected, and they set aside some habitat for it that sequestered a ton of carbon in the form of old growth forests but even other ecosystems that people don't think about storing a lot of carbon when scientists look at it, they do. Like the Mojave Desert. If we protect the tortoises that live there, desert plants are incredibly efficient at sucking carbon out of the atmosphere and storing it in the desert soils and prairies, like prairies have like 15 feet of healthy soil and root system. So protecting little endangered species like the Dakota Skipper butterfly, if we really protect its habitat, that habitat is going to sequester carbon. So if you add up all of those places from all around the country, protecting habitat for endangered species will help us fight the global climate emergency.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's really fascinating to think about how interconnected everything is and how it's really, you know, the chicken and the egg, so dependent on each other.

CURRY: For sure. And if we succeed in protecting 30% of lands in the next decade, and 50% by 2050, all of that protected land is really going to help stabilize the climate. So it's a win-win. We get to stay on the planet more wildlife gets to stay on planet.

BASCOMB: Tierra Curry is a Senior Scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity. Tierra, thanks so much for your time today.

CURRY: Thanks so much Bobby.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “UN Proposes Protecting 30% of Earth to Slow Extinctions and Climate Change”

- Read more about the Center for Biological Diversity’s “Saving Life on Earth”

- Click here to read the UN convention on Biodiversity’s draft plan for a global biodiversity framework

[MUSIC: Bernard Purdy, “Funky Groovy Jam Session” for Drummerworld]

Mangroves Thriving in a Warming World

In addition to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, mangroves are also effective in providing a shield during major storms. (Photo: Andrewtappert, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

BASCOMB: Scientists are sounding the alarm on biodiversity loss in nearly every corner of our planet. But with climate change some important ecosystems are actually expanding. Among them, mangroves. Mangroves are hardy trees that grow in salt water and serve as a first line of defense against hurricanes. They’re also a crucial breeding ground for marine life. And now, as the planet warms, mangroves are expanding their habitat both north and south, which may in turn actually help slow the advance of climate change. Brendan Rivers is a reporter for WJCT in Jacksonville, Florida and has the story.

RIVERS: Danny Lippi is walking through Nease Beachfront Park, just across the bridge from historic downtown St. Augustine. The park is dense with trees.

LIPPI: These are, all of these are mangroves.

RIVERS: Lippi a certified master arborist, one of the professionals the state allows to trim them.

LIPPI: I've been here since 1981, you know on and off, and I don't remember the mangroves like this when I was a kid.

RIVERS: Mangrove ranges historically wax and wane with the weather, but more mangroves are arriving in Northeast Florida and thriving as climate change raises temperatures. Lippi says as more arrive they're also growing taller, blocking waterfront views and greatly boosting demand for his services among homeowners.

LIPPI: In this situation, they're being forced to hire me.

RIVERS: But not everyone finds mangroves to be a nuisance. Nature Conservancy marine scientist Laura Geselbracht says their spread is helping reverse a global trend.

GESELBRACHT: A huge number of our mangroves, 35% worldwide, have disappeared and a lot of that disappearance has been the result of coastal development.

RIVERS: She says the more mangroves, the better, because the trees could actually help slow climate change. Mangroves absorb four times as much heat trapping carbon as rainforests, she says. At their current rate, scientists project they could push up into Georgia within the next decade, migration fueled by fewer freezes and stronger storms that spread their seeds.

GESELBRACHT: 25% of Florida's greenhouse gas emissions may be reduced by the amount of mangrove expansion over the next decade or two into Northern Florida and even beyond.

RIVERS: And they offer more immediate benefits too. Just ask Linda Mulay who lives in a waterfront condo in Port Orange just south of Daytona Beach. From her balcony she can see mangroves surrounding her building seawall. Mulay says when Hurricane Irma came through in 2017, she fared just fine.

MULAY: We didn't have any water damage. Which, storm surge is your biggest damage you have from a hurricane.

RIVERS: Researchers say if mangroves are wide and dense enough they can provide effective flood protection during storms. They also help fight sea-level rise by raising the height of the coastline. That's why University of California Santa Cruz researcher Michael Beck is partnering with FEMA and the insurance industry to fund their conservation and preservation.

BECK: Without mangroves, we think that on average, damages to properties for storms would increase by 16% annually.

RIVERS: He says they're credited with preventing $13 billion in property damage in the U.S. each year.

BASCOMB: Brendan Rivers is a reporter with WJCT in Jacksonville, Florida and host of the Adapt podcast. His story was produced in partnership with Climate Central with reporting by Ayurella Horn-Muller.

Related links:

- Click here for this story from WJCT

- Read more on mangroves here

- Brendan Rivers’ podcast, ADAPT

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Laysan Albatrosses Nest at Midway Atoll

A pair of adult Laysan Albatrosses. (Photo: Kristi Lapenta, USFWS, CC)

BASCOMB: Well, many of us may feel like hibernating through the winter but for the Northern Albatross this is the perfect time to get to work on nesting and raising chicks. BirdNote’s Mary McCann has the story.

Laysan Albatrosses Nest at Midway Atoll

[Laysan Albatross - groaning, bill clacking, whinnies]

Midway Atoll, a small island more than 1,200 miles northwest of Honolulu, is the winter home for nearly a million nesting albatrosses.

[Laysan Albatross moans, whinnies, bill clacking]

Most are Laysan Albatrosses, huge, handsome seabirds with white bodies and dark, saber-shaped wings six feet across. Laysans return to Midway in November to breed. Roughly 450,000 pairs wedge their way into a scant 2½ square miles of land, creating one of the world’s most spectacular seabird colonies.

[Laysan Albatross sounds – whinnies and bill clacking]

It may seem curious that Laysans nest in winter, when most birds nest in spring and summer. But these big birds forage mostly at night, so the longer hours of darkness in winter provide more time to find food for their rapidly growing chicks.

An adult Laysan albatross (background) and a young albatross chick (foreground). (Photo: Chuck Swenson, USFWS, CC)

Beginning in late January, when the single chick hatches, both parents will feed it for the next six months. And by mid-May, it may weigh seven pounds, even heavier than the average adult. The young bird will need that extra fat and energy, as it learns to fly.

[Laysan Albatross sounds - moans, whinnies, bill clacking]

By August, the once-noisy colony is all but empty — until next winter. I’m Mary McCann.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Laysan Albatross 959-2 (all sounds) recorded by E.Booth

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org January 2015 / 2020 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# LAAL-01-2013-01-02 LAAL-01b

https://www.birdnote.org/show/laysan-albatrosses-nest-midway-atoll

BASCOMB: For pictures, soar on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- See this story on the BirdNote® website

- Find out more about the Laysan Albatross at Cornell’s All About Birds

[MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “Hula Lady” on Wooden Boat, Dancing Cat Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Climate change has the Arctic warming at a faster pace than nearly any other region on earth and Norway is already feeling the heat. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Rob Curto’s Forro For All, “A Voz da Razao” on Forro For All, by Osvaldo Oliveira, self-published]

Norway’s Disappearing Winter

The city of Tromsø, Norway, during one of the country’s winter days. (Photo: Lee Dyer, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb. Scandinavia is nearly synonymous with cold and snow but a recent study out of Norway finds that’s beginning to shift. Oslo, Norway, the country’s capital is already experiencing 21 fewer winter days than just 30 years ago. And by 2050 scientists expect winter will last nearly half as long as today. For more, I’m joined now by Reidun Skaland, a climate scientist at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute. Welcome to Living on Earth!

GANGSTO: Thank you very much.

BASCOMB: What got you thinking about this question? I imagine, you know, 30 years ago isn't all that long people probably remember when winters were more extreme and lasted for longer.

GANGSTO: Yes, definitely, people are talking about it that the winter is milder and that we have less snow than we used to have. I think many Norwegians know which as they define themselves as skiers, they love going out to skiing and winter time and we say that the Norwegians, they are born with “skis on their feet,” and maybe that the expression will change because they're not so often conditions that are very good for going skiing anymore. And people will notice that, but there are also other consequences with milder winters, we see that the risk of getting different landslides, different type of landslides is increasing. And that is something that people may get a bit more worried about, and also by seeing more rain and problems due to heavy rainfall also in wintertime, that's something we are not so used to.

BASCOMB: So are you seeing flooding and things like that as a result then?

GANGSTO: Yes, both flooding because of the rivers and also in the cities, when we get very heavy rainfall in the city, you can have floods and water in the basements of the houses and so on.

BASCOMB: What about outside the cities in Norway, I'm thinking of the island chains in the Svalbard archipelago and the coastal areas?

GANGSTO: Yes, the coastal areas and the islands are the areas which notice most the changes. Here we have seen a very high increase in temperature so far, like four Oslo the temperature increase has been two degrees since 1961. But in Svalbard, it has been 5.6 degrees Celsius. So it's a huge increase in temperature compared to the Oslo value, and also compared to the global value, which is about one degree,

BASCOMB: Right? And 5.6 degrees Celsius, that's that's almost 10 degrees Fahrenheit, I believe. I mean, that's, that's a huge difference.

GANGSTO: It's a huge difference. Yes.

BASCOMB: And why are the islands off of Norway warming so much faster than than the mainland?

Reidun Gangstø Skaland is a climate scientist at Norway’s Meteorological Institute. (Photo: Courtesy of the Norwegian Meteorological Institute)

GANGSTO: Well, like for instance, Svalbard, here we have this very high temperature increase, mainly due to the melting ice and snow, because especially the Fjords and the sea around the island is usually covered or it was usually covered by snow and ice. And when this disappears, the surface gets darker. And that means that also it absorbs more heat from the sun. And then the warming happens much more quickly because of that.

BASCOMB: And what about the wildlife? How are the shorter winters affecting them?

GANGSTO: I think one main problem for the wildlife is that before when the winters are more stable, and cold, they would have snow covering the fields and they would get the grass below the snow without problems. But now we may first have some snow and then some rain and then some freezing again and there will be ice covering the grass and they will not access the grass that easily anymore. So I think like reindeers and elk and deers, they may have more problems getting food now and in future than they used to. So we have to be prepared for more extreme weather and the consequences that it's will give for Norway.

BASCOMB: Reidun Skaland is a climate scientist with the Meteorological Institute in Norway. Thank you for taking this time.

GANGSTO: It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- The Barents Observer | “The Tromsø-Winter Now 17 Days Shorter Than 30 Years Ago”

- Read more about Reidun Skaland on the Meteorological Institute’s website

[MUSIC: Pascal Roge and Denise Francois-Roge, “Ma mere l’Oye (Mother Goose): Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant (Pavane of Sleeping Beauty)” by Maurice Ravel, on French Masterpieces for Piano Four Hands, CD Baby (on behalf of Duo Plaisir)]

Redlining Linked with Extreme Urban Heat

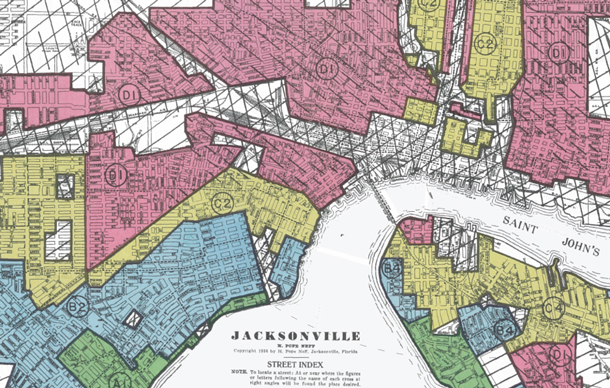

Jacksonville, Florida has a long history of segregation. (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

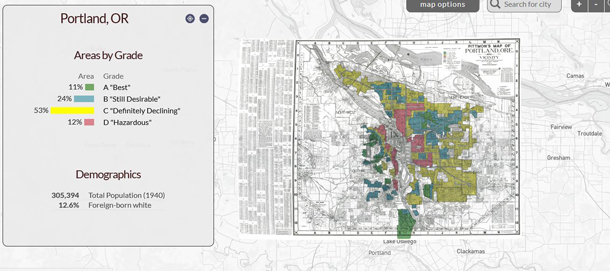

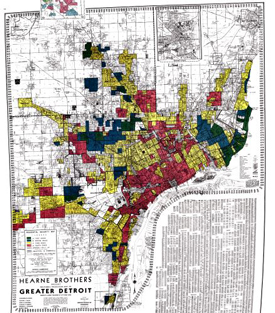

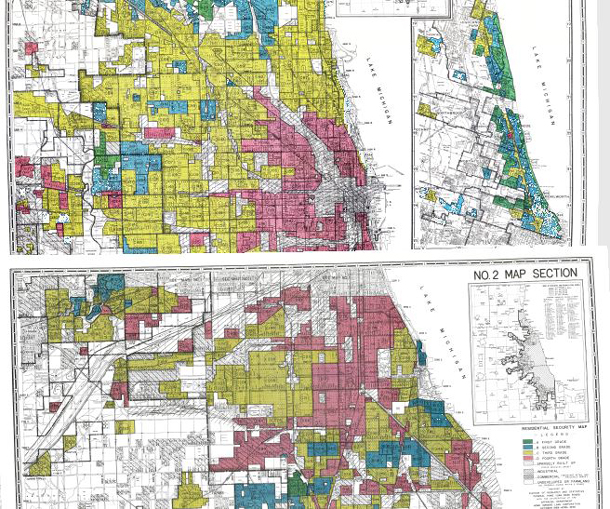

BASCOMB: In the 1930s, while the world was digging out of the Great Depression, the US government came up with a plan to ostensibly advise banks on better ways to lend money to would be homeowners. The federal government drew up maps of more than 200 cities and gave grades to individual neighborhoods based on their suitability to receive a loan. A-grade areas were outlined in green. They were largely suburban and white. On the other end of the spectrum, D grade neighborhoods were outlined in red. They tended to be in city centers and black. In fact, minority neighborhoods were more likely to be inside a red line despite similar household incomes, home age, and other risk factors in white communities. In a practice that came to be known as redlining, banks used the government’s racist recommendations to deny home loans to minority residents. Nearly 100 years later the legacy of redlining is still evident today in a myriad of ways, including the exacerbated effects of climate change. In a recent study published in the journal Climate, researchers found that redlined neighborhoods, still today predominantly made up of minorities, are up to 10 degrees hotter than other neighborhoods in the same city. A lead author of the study is Portland State University Professor, Vivek Shandas.

SHANDAS: What we wanted to look at is just one climate, a new stressor that we know is going to increase in frequency, magnitude and duration over the coming decades and that's urban heat. Urban heat kills more people than all other natural disasters combined in the U.S. and it particularly is a very selective killer in that the people who have died have been historically underserved communities, historically, black communities. And so we wanted to see was that policy that was fundamentally based on race and social class was that playing out to affect the communities today in terms of who's exposed to those intense heat waves at a much higher magnitude than others. And what we found was that pretty much across the country in the hundred and eight cities, we looked at those areas that were hotter, were those redline neighborhoods.

BASCOMB: And to be clear, I mean, this is the same city we're talking about. So you're sitting in Portland, Oregon, which I believe was the city with the highest discrepancy of temperature in these redlined areas versus non-redlined areas. But why is that? I mean, why within the same city are you seeing such a dramatic temperature difference?

SHANDAS: The temperature differences are largely a factor of differences in the physical environment. So, what is in those neighborhoods now that were formerly redlined. And what we see consistently is that those neighborhoods are often either right on top of or adjacent to industrial areas. Those areas are often where the biggest freeways or highways were put in, in the 1950s. We see those areas is often having a lot fewer trees and a lot more impervious surface or that kind of concrete or asphalt that really absorbs heat over time. And so this is a phenomenon that is consistent across these cities we looked at and these historically, redlined areas have the built environment that absorbs the sun's radiation and amplifies temperatures a lot more. And as you were saying Portland, Oregon is top of the list though, Denver, Minneapolis, Columbus, Jacksonville, Philadelphia, Louisville, Baltimore. They're all in that top range of cities as well.

BASCOMB: Well, what kind of effects do you see in communities that are hotter than others? I'm thinking of even crime. I mean, I know I get cranky when it gets hot out. And we routinely see spikes in crime rates in cities, particularly when it gets really hot. Do you think that any of that can go back to this policy?

Only 11% of Portland, Oregon was considered desirable for mortgage loans between 1930 and 1940. (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

SHANDAS: Yeah. So we've seen that people's behavior changes when it gets hotter. We've seen for example, more use of energy, we've seen greater hospitalizations, we've seen more issues of road rage and violence that happen when things get hotter in cities. And what that really comes down to is our mental health ability to cope as well as our physiological ability to cope and health impacts from increased heat as well. So we can talk about children that are exposed to heat. We've seen studies come out about how children at school are not able to focus are not able to actually do well and learn as a result of hotter classrooms or hotter environments. And so that can have a long-term effect on an ability to actually complete school. And that leads to a whole series of outcomes as well. We see this playing out in terms of our financial health; people are running their air conditioner much harder if they have access to air conditioning and have financial resources to run it. So that's money that's going away from other things like food or education or health that can be some of the basic needs for a community. And then of course, we have older adults, particularly those that have pre existing health conditions like asthma or any kind of heart condition. We've seen more recent work that's been done on stroke, brain health, in terms of heat, and that can have profound effects as well. Working with some folks at UCLA Medical School to try to better assess some of those impacts and there's no shortage of heat and health related impacts that are occurring.

BASCOMB: We had a story on the show recently, in which we talked a bit about the dramatic difference between white and African American babies and infant mortality rates. And the statistic that really struck me is that a black woman with an advanced degree is more likely to lose her baby than a white woman with an eighth grade education. So it's not about affluence. It's not about, you know, education. To what degree is it possible that living in hotter communities is putting a physical stress on pregnant African American moms and resulting in higher infant mortality rates for them?

Map of redlined areas in Detroit from 1940: 6% were considered desirable (marked in green), 14% was considered still desirable (marked in blue), 51% were considered declining areas (yellow), 28% were considered hazardous (pink). (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

SHANDAS: Right. Fascinating question about the relationship between race, health and climate and a lot of the study really has some potential directions. While we don't study that in this work right here, I will say that with redlining, we find that the communities living in historically redlined areas are still communities of color are still immigrant communities are still indigenous communities and, in part what that suggests is that if you have communities of color, like a black woman living in a formerly redlined area, what you're going to see is temperatures that are sometimes five eight, ten, twelve and we've even documented air temperatures of 20 degrees hotter in particular parts of a city. So, if you're talking about a 90-degree day for one part of the city, another part of the city could see 110-degree day. And once you cross that, around 98.6, about 37 Celsius degree our body is trying to cool down so our body uses sweat to be able to cool itself down. And I'm not a medical doctor though, I’m in collaboration with them. I've learned that this sweating process really helps us cool down though if the ambient temperature is hotter than 98.6 and if the humidity levels are high, we could reach this threshold called wet bulb temperatures, that's W-E-T B-U-L-B temperatures which are a point at which our body is unable to kind of cope and cool down. And so that stress that the body faces goes right into the womb that an unborn child is in and that's a level of stress that's part of that pregnant mother and that then affects the child. What we've seen in a project we're working on with five states and cities and five states where we're looking at birth outcomes in relation to heat and air quality, we've actually seen that the smallest babies have some of the biggest effects. So these are preterm births have some of the biggest effects from the mother being exposed to extreme heat and poor air quality. So what that means is that a child being born very small actually ends up being born even smaller as a result of this exposure. And the smaller the baby gets, the more that baby has to really struggle in order to be able to live and it leads to as we've learned from the field of epigenetics, long term consequences on the health and well being of that person. The effects of redlining then can really play out in terms of what the environmental conditions are that a person, let's say, in this case, a black woman is exposed to, and that can lead to long term consequences on their ability to manage their own as well as their children's health.

BASCOMB: Well, it's just, it's just shocking, really how, you know, a racist policy from, you know, almost a century ago, is persisting in so many different ways and has such long term health impacts on people that had nothing to do with that back then.

This is a map of the different levels of redlined areas in Chicago. The green areas represent desirable areas (A areas), the blue areas are still considered good but not a “hotspot” (B areas), the yellow C areas are considered declining areas, and the pink D areas are considered hazardous. (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

SHANDAS: Right, right. And you know, in public health, it's a very common phrase now to be talking about your zip code is more important than your genetic code. And I've heard that said by a lot of very impassioned and very committed public health staff and various agencies and community health workers, etc. And what occurs to me is that the fact that your zip code is so important for your health and well being has a lot to do with how we're going about planning our places and planning our cities. And that's really what a lot of this work kind of comes back to is, how did this policy really underscore the racial underpinnings of the country.

BASCOMB: So for somebody that's listening right now and nodding their heads in Yeah, you know what it is hotter where I live, then where I work. Maybe I'm living in one of these communities that's suffering from these racist practices, what can you say to those people?

Vivek Shandas is a professor of climate adaptation at Portland State University and co-author in this study. (Photo: Vivek Shandas)

SHANDAS: Part of my job is to study cities. And I've heard a lot about people really pointing and blaming and saying, you know, I wish people in that neighborhood would take better care of their place, or I wish they would be more engaged, or I wish they would be doing things differently. And there's a lot of this, that I hear from communities that I talked to about blaming communities of being kind of, quote, sketchy or being, quote, not really worth visiting. And these are things that really hit me pretty hard, because I see through studies like the one we did, that this was a very systematic process that actually is no fault of the people that actually live there. And I guess that's really kind of at the core of what I'm hoping that this study will help reveal is that these are kind of underlying challenges that have been there and a long time. And our work then in front of us is to be engaged with the planning that's happening in our backyard with the planning that's happening all around us and to be kind of really mindful about the fact that the decisions made today could have repercussions twenty, fifty, one hundred years later, and to kind of go into this planning process thoughtfully and with recognition that these historical practices are things we have to undo and things we have to center in our current work, climate or otherwise.

BASCOMB: Vivek Shandas is a professor of climate adaptation at Portland State University and co-author of the recent study. Thank you so much for taking this time with me.

SHANDAS: Thanks so much for your interest.

Related links:

- Click here for a virtual map of redlined zones across the United States

- Click here to read The Effects of Historical Housing Policies on Resident Exposure to Intra-Urban Heat: A Study of 108 U.S. Urban Areas

[MUSIC: Pat Donohue, “Ain’t Misbehavin’” on Jazz Classics for Fingerstyle Guitar Volume Two, by Thomas “Fats” Waller/Harry Brooks/Andy Razaf]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our executive producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth