March 6, 2020

Air Date: March 6, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Joe Biden’s Plan for a Clean Energy Revolution

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Former Vice President Joe Biden is running for President on a platform of bringing a divided nation together, on key issues including the environment. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering reports on Joe Biden’s version of a Green New Deal for clean energy jobs and more, and hears from voters on why they support his plan for addressing climate change. (08:23)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss how the Trump administration has pressed the EPA to disregard what its scientists have discovered about the dangers of the carcinogen TCE. Also, swing voters have taken note as they face the presidential election, and are reported to be wary of such environmental rollbacks. And ten years ago this week, BP ignored a memo warning against the faulty cement that contributed to the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon well, just six weeks later. (03:55)

Facing the Corona Virus Challenge

View the page for this story

Since late 2019, the novel coronavirus has been spreading throughout the world, sparking fears that it will grow to be a global pandemic. There are comparatively few cases in the United States, but with no vaccine or anti-viral treatments, public health officials are working hard to keep it that way, even though the US has lost some 45,000 public health employees over the past decade. Dr. Jonathan Quick, a professor of Global Health at Duke University, joins Host Steve Curwood for a look at the epidemiology of COVID-19. (10:51)

Harvard Students and Faculty Call for Divestment

View the page for this story

Students at Harvard are calling on the university to divest its $41 billion endowment from fossil fuels, and over 1000 Harvard faculty members have signed a petition in support of divestment. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering sat down with Caleb Schwartz, a senior at Harvard College and member of the Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard movement, to discuss why he and his peers believe their institution has a moral responsibility to divest from fossil fuels, and the implications of divestment on a broader scale. (09:19)

The Wizard and the Prophet

View the page for this story

Some believe technological innovation holds the key to solving environmental problems, while others look to nature for answers. In his new book, “The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow’s World,” Charles C. Mann explores the origins of “apocalyptic environmentalism” and techno-optimism through the lives of agronomist Norman Borlaug, a.k.a. the “Wizard,” and ecologist William Vogt, a.k.a. the “Prophet.” Charles C. Mann spoke with Host Steve Curwood at a Living on Earth Good Reads event in Boston. (14:26)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

200306 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Charles C. Mann, Caleb Schwartz, Jonathan Quick

REPORTERS: Jenni Doering, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

Part of the appeal of voters for Democrat Joe Biden is his call for climate action that puts Americans to work.

DAN: He wants to fix our broken electrical grid; renew all the rail lines with electric power, and he has a huge solar component to create renewable energy, and wind as well. With good-paying jobs; jobs for America, and power for America.

CURWOOD: Also, as the fiftieth anniversary of Earth Day approaches, the fossil fuel divestment movement at Harvard picks up steam.

SCHWARTZ: We don't think that we should live in a system where it's ok for a University to profit on the exploitation of the planet but that being said we also have the fortune that there is a very strong economic case to be made for the divestment of fossil fuels.

DOERING: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Joe Biden’s Plan for a Clean Energy Revolution

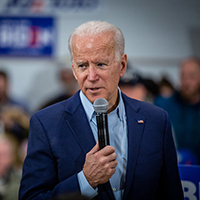

Joe Biden speaking with voters in Des Moines, Iowa in January 2020. (Photo: Phil Roeder, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston… this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

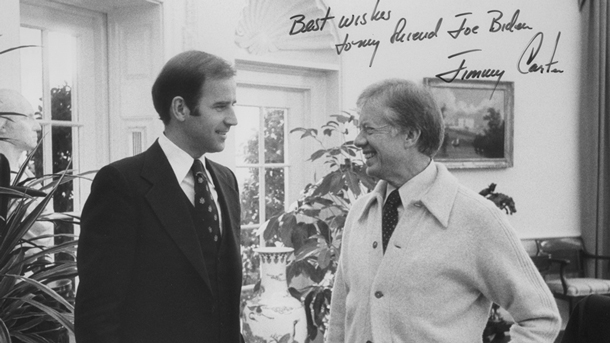

The Democratic presidential primary race has narrowed to Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and former Vice President Joe Biden. We covered the Sanders climate platform in an earlier broadcast, and today we’re taking a closer look at Joe Biden’s. Back in the 1980s as a Senator from Delaware, he introduced some of the earliest climate legislation and became known for his daily Amtrak commutes between DC and home. When Joe Biden served in the Obama Administration as Vice President, he was part of the team that got the 2015 Paris Climate Accord over the finish line. But in 2009 the Obama-Biden White House had missed a key opportunity to put a price on carbon and make a success of the climate change summit in Copenhagen. And a number of regulatory moves it made late in its second term have been rolled back by the Trump Administration. Still, Democrats concerned about the environment give Joe Biden credit for his record on the climate.

In Massachusetts, where the former Vice President barely campaigned, I found a surprising amount of support for him just before election day. Thirty or so campaigners had gathered on a cold and windy overpass of the Mass Pike on the eve of Super Tuesday.

[CHEERING, CAR HORNS HONKING]

Supporters wield Biden signs above the Mass Pike, trying to attract commuters’ attention and honks. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: This “Go Joe!” crowd had found a strategic sign-waving spot, and one bundled-up supporter couldn’t wait to say why she was there.

CAROLINE: I’m here to support Joe Biden. He’s been a champion talking about climate change way back in the ‘80s; I feel that he is our man to beat Trump, in the general election in November.

This is where all the commuters are leaving Boston, they’re all sitting in traffic as they’re leaving the city, coming this way. So it’s a good publicity spot.

[TRUCK HORN]

CAROLINE: Now I’m happy, I was waiting for that.

DOERING: A man wearing a Vietnam Veteran hat held a sign too.

President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden speak with CEO of Namaste Solar Electric, Inc., Blake Jones, while looking at solar panels at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science in Denver, Colorado. (Photo: Official White House Photo, Pete Souza)

ROBERT: When it comes to climate, we’re not gonna make it with another four years with Trump, and it’s very very scary. And the reality is, we have to really get serious about that, and I believe that all of the Dem candidates can do that, but Joe Biden uniquely has the best shot of winning. So I think the future of our democracy and the future of the planet itself really depends on this election.

DOERING: On Super Tuesday, Joe Biden was the preferred candidate among voters who said climate change was the most important issue to them, according to a Washington Post analysis of exit polls. Climate has been a key part of his campaign, although some of his opponents have called for more radical action. Back when the Biden campaign was still struggling, he spoke about his climate priorities at a town hall in Vinton, Iowa.

BIDEN: I think we have to get to the place where the single most focused issue for this country and the world is climate change. [APPLAUSE] It is climate change. And there’s a lot we can do about it. We’re the only country in the history of the world that’s turned great problems into enormous opportunities.

DOERING: For many Democrats, Joe Biden represents the promise of a return to a pre-Trump Presidency, but this time with a greater commitment to climate action than President Obama was able to achieve. Vice President Biden would leverage 3.3 trillion dollars in private investment to drive emissions down to net-zero by 2050, in what he calls a “Clean Climate Revolution”, starting with investment in low-income and minority communities. Here he is at the Democratic Primary Debate in Nevada.

BIDEN: By the way, minority communities are the communities have been most badly hurt by the way in which we deal with climate change. They are the ones become the victim. That's where the asthma is. That's where the that's where the groundwater supplies been polluted.

President Barack Obama presented Vice President Joe Biden with the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom with Distinction, during an emotional ceremony on January 12, 2017. (Photo: Official White House Photo, Chuck Kennedy)

DOERING: The Biden climate plan offers a Green New Deal, which would put a price on carbon and invest 1.7 trillion dollars in public funding over the next decade for clean energy technology, job retraining, electrification of infrastructure, and energy efficiency improvements.

BIDEN: What I would do is number one, work on providing over $47 billion we have for tech and for making sure we find answers, is to provide a way to transmit that wind and solar energy across the network of the United States; invest in battery technology. I would immediately reinstate all of the elimination of what Trump has eliminated in terms of EPA. I would make sure that we got the mileage standards back up, which would have saved over 12 billion barrels of oil, had he not walked away from it, and I would invest in rail.

DOERING: Like other proponents of a Green New Deal, Joe Biden says climate change presents an opportunity to create jobs, especially good-paying union jobs. That resonates with members of the Local 103 chapter of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, who came out to support the Biden campaign on the windy Mass Pike. Among them, Dan Daly, who has run for Boston City Council.

Senator Joe Biden and then-President Jimmy Carter in the 1970s. Joe Biden focused his 1972 campaign for Senator from Delaware on civil rights, the environment, and “change”, among other matters. (Photo: Office of United States Senator Joe Biden, public domain)

DAN: I’m an electrician. Joe Biden supports the IBEW, which I am a member of, and he has a great infrastructure plan: He wants to fix our broken electrical grid; renew all the rail lines with electric power, and he has a huge solar component to create renewable energy, and wind as well. With good-paying jobs; jobs for America, and power for America.

DOERING: The Joe Biden event was powered by enthusiasm, especially from a middle-aged woman wearing a bright red coat.

BRENDA: Woohoo!! Thank you, thank you!! [cheering]

[CARS HONKING, STREET TRAFFIC]

BRENDA: The future of America is all about taking care of our climate, taking care of our planet. And Joe Biden is one of those people who will do that.

DOERING: As traffic crawled along the Mass Pike, a 22-year-old Boston College student said the climate crisis demands a leader who can take charge, and put pressure on the rest of the world to do its part.

22-YEAR-OLD: Oh, it’s very important, because as a young person, it’s something I’m going to have to live with my entire life, and it’s really the existential threat to the planet. So I think it’s very important, it’s one of the main reasons I’m supporting Joe, actually; I think that he would be uniquely able to bring a coalition of nations together to fight a problem that we alone as a country cannot solve by ourselves.

DOERING: And that’s one of Joe Biden’s key points.

BIDEN: We make up 15% of the problem, in the United States of America. 15%. The rest of the world is 85%. If we get, if we went to perfect, we didn’t have a single bit of emissions going from the United States -- which is not rational, there will be some emissions. But if we’re able to do that, farms are gonna, still gonna flood; you’re gonna still find yourself with exceptionally warmer winters and warmer summers, you’re gonna see droughts, you’re gonna see a lot of things because the rest of the world, the 85% of the emitters around the rest of the world are gonna require some international cooperation and that requires a world leader who can pull the world together.

Joe Biden campaign signs outside a polling place in Dorchester, Massachusetts on Super Tuesday, which gave his campaign a major boost. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: That’s a key reason why a voter at the Beech Street Center in Belmont, Massachusetts decided to go for Joe Biden on election day.

PHILIP: I think he understands the world as a global village and therefore we have duties and responsibilities beyond our borders to make sure we are operating on the same page when it comes to keeping our environment clean, for all of us. And therefore when he talks about solving environmental issues and the USA taking the lead, he knows exactly what he’s talking about.

DOERING: For this man, climate change is all too real.

PHILIP: Climate change is here with us. In fact, this winter, I’m calling it, “the winter that never was”.

DOERING: Another Belmont voter agreed.

SENTHIL: Like all responsible human beings, I’m extremely concerned. More than extremely concerned; I’m petrified! [laughs] Yeah, so it certainly informed my thinking.

DOERING: He hopes his vote can help change the outcome for climate policy.

SENTHIL: The political will to do something is not they're currently in the US gov’t. And without the political will, the steps that individuals take are good things, but the big push has to come from government.

DOERING: He told me he thinks Joe Biden has the best shot at leading this country and the world on addressing climate change.

And by the way, thanks to our politics team, Isaac Merson and Anna Saldinger, for their help on this story.

Related links:

- Joe Biden’s Climate Plan

- InsideClimate News | “Joe Biden on Climate Change: Where the Candidate Stands”

- MIT Technology Review | “How Biden’s climate plan stacks up to Bernie’s”

- Hear our story on the climate legacy of the other Democratic frontrunner, Bernie Sanders

[MUSIC: The Jim Cullum Jazz Band, “Burnin’ the Iceberg” on Chasin’ the Blues, by F. Morton, Riverwalk Jazz]

Beyond the Headlines

Swing voters are very influential, and candidates’ attitudes towards environmental issues are proving to be a crucial determining factor in their vote. (Image: Tom Arthur, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, it's that time of the program when we connect with Peter Dykstra on the line there in Atlanta. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. What do you have for us today, Peter? It's the political season, huh?

DYKSTRA: It's the political season, Steve, and we'll get into that in a little bit. But first, one microcosm of the political tendency of the Trump administration to roll back and negate its own science and to roll back environmental regulations. It comes from the website and radio program Reveal. Reveal is distributed by PRX just like Living on Earth is. And veteran environmental reporter named Elizabeth Shogran dove into documents proving that the Trump administration pressed EPA to ignore its own scientists in regulating Trichloroethylene, a known carcinogen, whose nickname is TCE.

CURWOOD: And so, the military, in particular, uses a lot of it to keep equipment going and on Air Force bases and such, and it winds up in the water. And in particular, I think it contaminated a lot of water at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina.

DYKSTRA: Camp Lejeune was the first major case of TCE contamination. It's been found in over 800 Superfund sites, in municipal water supplies, on other military bases. There are several determinations by EPA, by the Health and Human Services Department, by international agencies, that TCE is a known carcinogen. A recent study found that it's been linked to heart defects in fetuses.

EPA scientists discovered that the commonly used chemical trichloroethylene damages fetal hearts. (Image: Joshua_D, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Difficult. Hey, what else do you have for us? Maybe something now from the political world?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, I apologize in advance for a little bit of punditry. If you don't watch political coverage on cable news, let me remind you why you don't, and here goes my very brief dive into punditry. Swing voters. That's the name that the bean counters give to voters who voted for the Democrats in 2012, then switched parties and voted for Trump in 2016 or voted the other way around. Recent focus groups conducted by two nonpartisan research groups say that those swing voters, the ones who are key to just about any election are very very wary and unsupportive of Trump's environmental rollbacks across the board.

CURWOOD: You mean things like 'hey, maybe TCE isn't such a bad thing, huh?'

DYKSTRA: TCE, climate denial would be another large area, endangered species protection, drilling for oil and gas on public lands, trying to revive the coal industry. You name it, it's an all service swamp.

CURWOOD: Yes. What do you see from the annals of history now when you take a look back?

DYKSTRA: We're going to look at the 10th anniversary going back to March 8, 2010. On that day a memo was sent by Halliburton, the oil services company, to BP warning that the cement mixture they used to seal wells in the Gulf of Mexico was, quote on quote, "unstable". And of course, six weeks later, the Deepwater Horizon well blew out, killing 11 workers and causing the biggest offshore spill in history.

CURWOOD: I guess that's a concrete example of paying attention to your memos.

The tragic explosion at the Deepwater Horizon rig killed eleven workers. (Image: USEPA Environmental Protection Agency, Flickr, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: And that's a concrete example of a really bad pun, Steve, but we'll let you get away with it. Both BP and Halliburton later gave public assurances that the concrete wasn't the problem until that memo came out later in court documents.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And sometimes a pundit.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, Steve, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: All right. Thanks, Peter. And there's more in these stories that the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Reveal News | “EPA Scientists Found a Toxic Chemical Damages Fetal Hearts. The Trump White House Rewrote Their Assessment.”

- Concern for climate policy is spread across the political spectrum

- The Guardian | “BP Was Warned About Cement at Gulf Disaster Well”

[MUSIC: The Jim Cullum Jazz Band, “Tight Like This” on Chasin’ the Blues, by L.A. Curl, Riverwalk Jazz]

DOERING: Coming up –the new coronavirus and human ecology. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Jim Cullum Jazz Band, “Tight Like This” on Chasin’ the Blues, by L.A. Curl, Riverwalk Jazz]

Facing the Corona Virus Challenge

The novel coronavirus COVID-19 has spread to dozens of countries around the world since it was first reported to the World Health Organization on the last day of 2019. (Photo: Prachatai, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Quarantines, school closings, employees stuck working from home, the falling stock market. All of these disturbing events are thanks to a global wave of infection from novel coronavirus Covid-19 that has been spreading around the world since it was first reported to the World Health Organization from Wuhan China on the last day of 2019. And while now there are only a handful of countries where people are suffering and dying from this new coronavirus in large numbers fears of a global pandemic are rising. Though there’s still relatively few cases in the United States public health officials are working hard to keep it that way and there is little margin for error as there is no vaccine or antiviral medicines that seem to work against Covid-19. But for those people who do get very sick there are only limited numbers of ventilators available for intensive care. Joining us now for some background and perspective on the outbreak is former World Health Organization official Dr. Jonathan Quick. Dr. Quick is also author of the book The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It. Dr. Quick welcome back to Living on Earth.

QUICK: Thank you, Steve. It's good to be here.

CURWOOD: You know this time of year is often called the cold and flu season since these diseases seem to make their rounds about this time of the year in the Northern Hemisphere, how does the coronavirus compare to these other illnesses?

QUICK: Well, it's similar in the sense that it's a respiratory transmission, it transmits by respiratory droplets. It has a wide variation in severity with the coronavirus, the current one, about 80% is mild and asymptomatic, but it kills very much the same way as the as the flu does. It basically gets in and breaks down your defenses in your respiratory system. And then it's typically a bacterial pneumonia that kills you in the end. That's what's doing it for the coronavirus cases. That's what's doing it for today's influenza cases. That's what did it 100 years ago for influenza.

CURWOOD: So, what will be the worst case scenario, and how likely is that outcome?

QUICK: When you get a new virus like this, there's several possible outcomes. 2003, that was the first global Coronavirus outbreak. That was the SARS outbreak, out of China, the same kind of dynamic. That virus went global, and it hit 27 countries in a matter of weeks, there was a strong rapid public health response. And it was done by July, and it hasn't come back. That's the best outcome is that the virus, that good rapid public health response, puts that dragon back in the box and we don't see it again. The next best is you get a big outbreak, you got a good vaccine, and you wipe it up then. We don't have that. So, the worst possible outcome for the coronavirus, that it gets embedded in the population around the world and it continues. And we can hope for a seasonal dynamic, that when it gets warmer and all, the disease will go down. But we have no evidence yet that that is going to be the case with coronavirus. So, the worst case is that it's it's not seasonal, it doesn't go away in the warm weather. It sticks with us and we have a tough 12 to 18 months as we work hard to get a vaccine.

CURWOOD: What is it about our coronavirus response here in the United States that is working and what's not working?

QUICK: Well, what's working, first of all, we're prepared. And we were ready to get going on things. The bad news is that there's been some early missteps. One of the most troubling is the problem of getting the test kits going. Because the question that you want to know when you've got an outbreak is where the case is, how many are there, is that number going up each day or down each day. That's how you know how you're doing. And if you can't test, you don't know. We have been in the same cycle, in this country, of panic and neglect, in terms of our funding of the basic public health preparedness systems. When there's an outbreak, you get to the point where there's fear, there's panic. Health officials and political officials want to do something. So they, you know, they pass emergency spending. They make plans, they make promises to improve the systems and all that. And then when the headlines are gone, the disease has gone away, then other things take attention. And we de-fund and de-staff. The case in point: after 9/11, back in 2001, the Congress approved a national public health emergency fund. And they funded it well. Over the next few years it started trickling down, the funding. And then, with the bird flu in the mid 2000s. It went back up again. Then it started trickling down. And with the effect of the financial crash in 2008, over a period of six years, we lost 45,000 public health professionals in the US. Because we haven't kept up on funding those preventive services and the readiness, we did not start at a point of strength, as strong as it should have been. Overall the response has been strong, good and appropriate, but nowhere near what it could have been and should have been with the right funding and continued support.

A vaccine for this strain of coronavirus, COVID-19, is unlikely to be through testing and ready for public use until next year. (Photo: Government of Prince Edward Island, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: When you're dealing with an outbreak like this, what do you see as a more effective path, to focus on actions taken by institutions or individuals?

QUICK: When you don't have a vaccine and you don't have an effective medicine, your defense is is basically: find and isolate the sick, quarantine the exposed, treat the sick, keep the rest of the health service going. Those first critical things, those depend heavily on public trust, public cooperation. And what we saw vividly 100 years ago was St. Louis was one of the most successful cities in the 1918 pandemic, because they had a health commissioner that brought people together, that met with the press, that engaged people. And other cities that didn't have that trust, that didn't have that communication, there was a four-fold difference in the death rates among cities in the US, in good part because of whether they were able to keep trust and confidence and cooperation with the public.

CURWOOD: So, sounds like you're saying that good institutions are much better situation than every person for him or herself.

QUICK: Absolutely.

CURWOOD: Where are we on that scale, do you think in the United States? How are public institutions? What's the level of public trust?

QUICK: At the local level, the public health departments are known and seen by the public and are doing a super job, the state health departments are, the National Institute of Health and the CDC, those are all institutions which which I think have good trust. A critical thing for the trust is clear, credible, consistent communication. And a core principle is you tell people what you know, when you know it, you tell them what you don't know and, and keep them up to date. You don't mix in hunches and all if if you're somebody that a lot of people listen to.

CURWOOD: Now, Dr. Quick every year, a flu vaccination is created in the hopes of minimizing the outbreaks of influenza. How close are we to being able to expect a vaccine for this coronavirus do you think?

QUICK: Good news is that there's well over a dozen efforts going on to develop a vaccine. We've moved the fastest we've ever moved from having a new virus to the point where we've got vaccines that are now ready to go into testing. So, we're very close on that, moving quicker, but it's still probably at least a year off before we have vaccines that are proven to be effective and safe in humans.

CURWOOD: Now, what about the treatment side here for these outbreaks? Doesn't seem that the health system is really prepared to deal with huge numbers of people all of a sudden needing treatment and management all at once. What should be done?

Dr. Jonathan Quick is a professor of Global Health at Duke University’s Global Health Institute. (Photo: Courtesy of St. Martin’s Press)

QUICK: No, yeah, that's absolutely true. You know, countries used to have it backwards in the sense they'd say, we'll invest in roads and railways and all, and then if we have enough time and money we'll invest in health and education. What we know very clearly now is those countries that invest adequately in health and education and provide universal health coverage to the population, they actually do better economically, it's a good investment. So we're under-investing in health systems around the world and and that leaves most countries unprepared. But we also need to invest in a way where our resources go to those health activities that are the best value, that save the most lives.

CURWOOD: Before you go, Doctor, any advice you want to give us on a more individual level here in the United States? People want to know, what about going to public gatherings? Should we stay away? What about using public transit? That sort of thing.

QUICK: Well, first of all, good health hygiene, hand washing. If you're sick, wash your hands before you get on the subway. But otherwise wash your hands when you when you get off. That sort of good personal public health habits. Also, look at your immunizations. I mean, pneumonia is a disease that you can get immunizations for, older ages and all. But beyond that, keep track of where the information is on your community. And if there's been no identified coronavirus at all in your community, then if you feel safe enough to get in your car and drive the car and to go out in public during flu season, I wouldn't worry about coronavirus if it's not in your community.

CURWOOD: Professor Jonathan Quick is at the Duke Global Health Institute and author of The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today. Dr. Quick.

QUICK: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- More on Dr. Jonathan Quick

- Click here for our last interview with Dr. Jonathan Quick

- The End of Epidemics website

[MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “E’Ku’U Morning Dew,” on Moe’uhane Kika: Tales From the Dream Guitar, by Eddie Kamae/Myrna Kamae/Larry Kumura, Dancing Cat Records]

Harvard Students and Faculty Call for Divestment

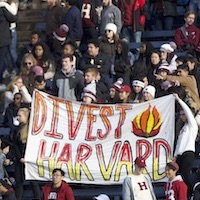

Students calling for Harvard to divest from fossil fuels hold up a sign at a Harvard University football game. (Photo: Courtesy of Caleb Schwartz)

DOERING: Students concerned about climate change are making a case for divesting their university endowments from fossil fuels. Already over a thousand institutions, including pension funds and faith groups, have begun divesting from coal, oil, and gas, totaling an estimated $14 trillion in commitments. Students at Harvard have been calling for divestment for years, and they’re pushing Harvard to divest its massive endowment from fossil fuels by Earth Day 2020. Their professors have shown support for divestment as well: over 1000 Harvard Faculty members have signed a petition calling for it, and recently the Faculty of Arts and Sciences voted 179 to 20 in favor of divestment. President Lawrence Bacow has said the Harvard Corporation will make a decision on divestment by the end of the 2020 Spring Semester. Caleb Schwartz is a senior at Harvard College and an organizer for Divest Harvard, and he joins me now. Caleb, welcome to Living on Earth!

SCHWARTZ: Thank you so much for having me.

DOERING: So how much does Harvard University currently invest in the fossil fuel industry?

SCHWARTZ: That is a great question. We do not know how much Harvard University invests in the fossil fuel industry, what we do know is that Harvard University has a 40.9-billion-dollar endowment, which is larger than over half the world's country's annual GDP. There's a huge amount of money and anywhere between 1 and 2 percent of it is disclosed at any given time because Harvard University has to disclose some of its direct investments to the SEC. So in August, we analyzed the 1% that was disclosed at the time and found that out of that one percent 5.6 million dollars were invested directly in the fossil fuel industry and production or distribution. So those are the companies whose business model depends on selling fossil fuels. And if you were to scale that up to the entire endowment, that would be $560 million out of the entire endowment invested in the fossil fuel industry, which is really just a guess. It could be much more could have over a billion dollars invested in the fossil fuel industry. But really any amount would be too much.

DOERING: So in addition to asking for this change from the president, from the Harvard Corporation, what power do you as students have to actually change the system and ensure that your university divests from fossil fuels?

SCHWARTZ: Sure, yeah. So the question of student power is a really interesting one, because ultimately, this $40.9 billion endowment is in the hands of 12 people on the Harvard Corporation and that very small number of people, and we're not even really sure how those people are selected It’s not transparent. They're the ones who control the endowment. So, what we believe is in that student power can put a ton of pressure on those 12 people who are in charge and if we make you know enough of a noise and kind of enough of a strong moral argument that all of a sudden, you know, thousands more students will join into the movement and thousands of more alumni is and hundreds more faculty. And that is something that Harvard can't ignore when you have over 1,000 faculty members signed on to a divestment petition and when you have, you know, hundreds of students disrupting your largest football game. And you have really high profile alumni such as Al Gore and Desmond Tutu writing letters asking the university to divest. So we don't have any voting power over the endowment. But we are seeing this really inspiring movement of student power, not just in Harvard, but all around the country, of students really trying to put pressure on their universities to do the right thing. And we think based on historical examples, that it really can work.

DOERING: So you're making a strong moral case. To what extent do you think there's also a financial case for moving away from fossil fuel investments in university endowments?

Over Harvard 500 students rushed the field at the annual Harvard-Yale Football game in 2019 to disrupt the event and call for fossil fuel divestment. (Photo: Courtesy of Caleb Schwartz)

SCHWARTZ: Sure, yeah. So for us, the students, I think the moral case is the primary one that we're trying to make. I think that we recognize the climate crisis was created by the systems of finance and extraction and exploitation that currently are the dominant systems of our economy. So we want Harvard to divest for moral reasons. We don't think that we should live in a system where it's okay for a university to profit on the exploitation of the planet. But that being said, we also have the fortune that there is a very strong economic case to be made for the divestment of fossil fuels. In September, the University of California divested its endowment and pension funds, which totaled $80 billion. And said, basically, this was a purely economic decision. Now, that kind of reasoning was disappointing, obviously, for the activists of the University of California who had fought for years and years to win this battle. And I personally don't believe that that you know, economics was the only reason I think that it was really the hard work of activists to put this issue on the table. But when you have a highly regarded institution divesting $80 billion for economics, you know, that's something that you should pay attention to. So combined with the moral case, there is a really strong argument for Harvard to divest.

DOERING: So Caleb, what would divestment actually mean for students and faculty?

SCHWARTZ: So the university administration wants us to believe that divestment would hurt the operations of the university in some way that maybe students would have received less financial aid and faculty would receive less research money, but the truth is that Harvard is the wealthiest University In the country and world. So we don't believe that divestment seeing that fossil fuels are already a risky investment would actually hurt the operations of the university. And when the Harvard Corporation says that its fiduciary duty is to maximize the returns on its endowment, regardless of the morals of their investments, and that if they were to do anything less than get as much money as possible out of the market, then they wouldn't be doing their duty. We really question that sort of reasoning. And that's really troubling to us because its mission is not to make as much money as possible, its mission is to, you know, make the world a better place through its research activities and through the kind of scholarship it does. So investment in the fossil fuel industry is not making the world a better place. And the kind of, you know, economic reasoning that says we have to be invested in the fossil fuel industry it just really doesn't hold up.

DOERING: So make the case for the other side for me, why shouldn't Harvard divest?

SCHWARTZ: Sure. Yeah. So there are really two things I think about when I hear this question and one is that divestment is hard. You know, Georgetown University just committed to divesting its endowment, and it's going to take them about 10 years to really pull out of all these investments, we don't think that Harvard is going to be able to commit to their divestment tomorrow and then the next day, they'll, you know, say, okay, our endowment is Fossil Free. They, you know, use mutual funds and they're going to need to direct their money managers to find ways to pull out of the investment. So it's hard, it will cost some money, it might temporarily, you know, cost the endowment. But like we're saying, these investments are a huge risk. So that's one reason. The other reason, I think, gets kind of more into the politics of people governing the university. And if I am on the Harvard Board of Overseers, or I'm on the Harvard Corporation, and I have strong ties to the finance industry, or I'm a top lawyer for Exxon Mobil or I, you know, worked in banking, or I work in private industry, you know, I'm probably going to have connections to the fossil fuel industry in some way. And so if those people are to make these choices to divest the endowment. And then they go return to their hedge fund and try to do business with Shell, you know, the shell might be upset, they just say, Hey, you know, why did you take this moral stance against me in this other sector, you know, I'm out and do business. And we're able to look at all these figures, you can go on to the Harvard Divest website and see some of the connections that we pointed out between members of the corporation and the oil industry and say that this is not a trivial at all. These are people who have a vested stake in the continuation of the fossil fuel industry for personal reasons. And so they're gonna be less likely to take a stance. And really, if you think about Harvard as an institution, it's, you know, one of the oldest institutions in the United States, it might be the oldest Corporation in the Western Hemisphere. Their power is derived from this kind of institutional prestige. And they historically haven't been on the side of social progress because they're so tied to these investments that hold back social progress. So we're hoping it's going to be different this time.

Students at universities across the country have been calling for their institutions to pull their investments in fossil fuel companies since the fossil fuel divestment movement first gathered momentum in 2010. (Photo: Courtesy of Caleb Schwartz)

DOERING: I feel like I've heard this argument, you know, if we divest from fossil fuels it’s the slippery slope, we're gonna have to start divesting you know from prison structures. And all these other, you know, morally repugnant investments that we're in. How do you respond to that? What's your response to an institution like Harvard boking at divestment from fossil fuels? Because it is this like a slippery slope, where you'd have to then remove these other investments on moral grounds.

SCHWARTZ: So I think that kind of reasoning is really representative of what's broken about our financial system now. I mean, to say that the market is just going to do what it does. And we shouldn't really consider the morals of our investments are really wrong. It's putting our planet in jeopardy. Harvard has divested before from apartheid from tobacco from an oil company that was had connections to genocide in Darfur. There is a line that the Harvard management company has been willing to admit that if the investments are classified in its criteria, we don't know what its criteria are, but if it classifies a set of investments as morally repugnant and pass this line, it will divest, and it's saying fossil fuels are not past that line. So our question is, why not?

DOERING: Caleb Schwartz is a senior at Harvard College studying environmental science and public policy and a member of the Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard campaign. Thanks so much, Caleb.

SCHWARTZ: Thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate it.

DOERING: Harvard University declined to provide a spokesman to be interviewed, but they sent a statement from President Bacow that you can read on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Click here to read a statement by Harvard’s current President Larry Bacow on confronting the climate crisis and divestment at the University

- Read a statement summarizing Harvard’s current position on divestment by its previous President Drew Faust in 2013

- Click here to read more about the fossil fuel divestment movement at Harvard

- Read more about Harvard University’s Climate Action Plan

- Click here to see which institutions have committed to divestment from fossil fuels

[MUSIC: Michael Johnathon, “Woody’s Poem” on Legacy, by Franz Schubert/Woody Guthrie (arranged & adapted by Michael Johnathon, Poet Man Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – balancing human values and technology. Keep Listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt, and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Booker T. & the MG’s, “Time Is Tight” (on 7-inch single), by Booker T. Jones, Al Jackson, Jr., Donald "Duck" Dunn, Steve Cropper, Stax Records]

The Wizard and the Prophet

A “guano island” off the coast of southern Peru, where birds are covering rocks with guano, which is collected and used as fertilizer. William Vogt was assigned to increase the amount of guano could be sold by the Peruvian government. (Photo: Dbrgn, Flickr, CC by SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

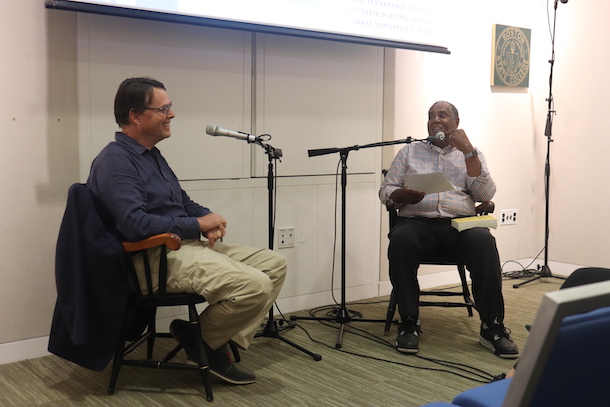

When it comes to solving the problem of climate change, two common solutions are in seeming opposition. One set of proposals sees technology as a major answer, using approaches such as carbon-free energy production and geoengineering to remove carbon from the atmosphere. Another view looks to shaping human civilization with conservation and community building to decrease consumption and lighten the burden on the planet’s climate systems. After World War Two concerns about feeding a rising world population led to work by Norman Borlaug to launch a green revolution using intensive farming as a technical solution. At about the same time ecologist William Vogt studied traditional societies to develop ways to feed people based on conservation concepts and respect for naturally occurring processes. In his book, the Wizard and the Prophet author Charles C. Mann discusses energy consumption, environmental sustainability, and food security through the life stories of these two amazing twentieth-century scientists. He joined me at the Good Reads on Earth Live Event at UMass Boston.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: So let me get this dilemma, this dichotomy right. On the one side, do you have what you termed the Wizard Norman Borlaug coming up with these amazing ideas, except that the Wizard's alchemy, at the end of the day kind of bites us, and then Vogt who's supposed to be a prophet? But he's saying is bad news. So the guy with the hope that doesn't work. And the guy who is the son of the philosopher, the theoretician saying, well, it won't work. I mean, it leaves us with, what are we going to do?

MANN: Well, this has to do I think, fundamentally with people's values. And that's one of the central arguments of the book is that, that the choices that people make, you know, obviously, they're informed by science and facts, but ultimately, it comes down to a vision of what kind of world you want to live in. And Borlaug, who had worked his entire childhood, just like a dog on a farm thought of agriculture as this drudgery that you should spare as many people as possible, and he envisioned essentially a world of, you know, a glittering world of high tech cities surrounded by vast areas of undisturbed land, and then ringed by these little, super intense areas of agriculture ideally done by robots. And, you know, that's a vision in which you're trying to maximize human individual potential. Vogt saw that as a nightmare and said, no, we need to have more inhabited countryside where people live closer to the earth, where there are these kinds of giant cities or cesspools of corruption, we need to have neighborhood control over things. We need to have things done at a much, much smaller scale so that people can interact with the earth. And this really goes back to people like Jefferson and Hamilton or Rousseau and Voltaire. I mean, these are ancient philosophical arguments that we've, you know, put on modern disguises. But in the end, a great deal of the dispute within the environmental movement are just from just that these basic value fights.

CURWOOD: Well I think the spoiler alert for people who get to read your book is that there is some optimism in here. Yeah, even though we're at this rather dark spot because it sounds like you go tech, and you have a bad outcome and I think people through the Luddite spear at Vogt Right?

MANN: Right, right, right. Which is not actually fair because what their prophets are talking about is no technology, but a different kind of technology. And I, you know, give the example in the book of a farm that I spent some time on in Northwestern Illinois, which is a remarkable thing it grows 1000 different crop varieties, and its complexity mimics that of a natural ecosystem. But it takes an enormous amount of knowledge to do that. And they do things like have solar power greenhouses, and when I was the last visiting there, they were experimenting with monitoring the crops by the drone so that there's a real embrace of technology. But it's a kind of a decentralized you know, whole earth catalog type of technology rather than massive nuclear power plants and centralized facilities that produce genetically modified seeds and all the rest of that kind of stuff.

CURWOOD: Now, this is a very well researched book and I'm guessing that in a way, you really got to know, Norman Borlaug and William Vogt it at a fairly deep level. What were your personal takeaways from each of these men?

Norman Borlaug worked in the Sonora Desert creating high-yield disease-resistant wheat varieties. He shaped what we now know as the Green Revolution. (Photo: Texas A&M Agrilife, Flickr, CC BY=NC-ND 2.0)

MANN: Well, I wouldn't want to be married to either one of them.

You know, and this wasn't because they were bad people or anything, but they're both pretty obsessed. And Borlaug's wife, at one point estimated that in the first I don't know, I can't remember if it was 40 or 50 years of their marriage they were married for a very long time, that he spent four years at home. And this was because he was out in the field working, you know and working with poor farmers. He was a very, very genuinely decent, modest person, but he's also quite limited. He went to college and he didn't take any kind of economics. He didn't take sociology, and didn't take history, and I am afraid that's reflected in this. It never occurred to him that one of the byproducts of what they were doing would be if you can produce more food from the same amount of land, which is what his goal was, it would make that land more valuable. Eventually, it would become worth stealing and that's just what happened all over the world in the wake of the Green Revolution. The land became more valuable and with the active assistance of governments, poor people were pushed off the land and it was, you know, consolidated and taken, taken over and, you know, had some extremely detrimental effects. We ended up with these giant mega cities, you know, like Mexico City or Sao Paulo or Jakarta, you name them, where the peripheries and slums are entirely composed of people who have been pushed off the land. And you know, this was just not something that Borlaug who was you know, focused on the right in front of him the type of guy could really grasp.

CURWOOD: And reading parts of this in your book, it reminded me of what happened as really kind of the end of the Dark Ages in Europe begins and you move towards enlightenment in the Renaissance or whatever you want to call it. And especially in the UK, you see something known as enclosures, suddenly, you have to put up boundaries around the productive places. In your view, what is this human impulse to put the borders around these things that produce literally the food that we're able to survive with?

MANN: I think it's a combination of different things. I mean, you know, smallholders are usually living quite precarious lives, and they're very understandably anxious about, you know, not being ripped off. And they don't have the room in a certain way to be wildly generous because they're feeding their families. And the same thing is true with corporations. Agriculture is a low margin business mostly. And so you know, the economic system that we have set up, which is Based on cheap food means that all the people who produce it from the top to the bottom are, you know, feeling pressed down, they can't increase prices. And the result is that you have people fighting for every last nickel. And this has meant cheap food for people in the cities, which was the official, you know, that was the explicit purpose. But it's also meant a lot of misery in the countryside. And indirectly, I think it's led to the situation we have now and many of the developed world where the only people that can really afford to invest in these things are people can really pile up pieces of land. So this is all part of this process of dispossession and this is the sort of thing that Vogt said hey, this is terrible.

CURWOOD: Yeah. So talk to me more about your takeaway from William Vogt. Well, Vogt was another other records. You don't want to be married to him either.

MANN: No. In fact, he was a very lonely voice and was not easy to be a pioneering environmentalist in the 1940s and 1950s. This is the time when The US has just won the war. And we need to have science out there. We need to get these people off the land and, you know, have productive workers and all this. And here is Vogt who wasn't trained as a scientist, he was a mad ornithologist. I should also say that he got polio when he was 13. And so he spent most of his life in pain. So he was a very gutsy guy. And he befriended some of the great ornithologists of the 20th century, people like Ernst Meier at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where he lived. And when, you know, Broadway collapsed in the wake of the Great Depression, they got him a job. Ultimately, they got him sent to Peru, where he was supposed to try and preserve these birds that produce guano, bird excrement that was at the time one of the main sources of fertilizer and one of the main sources for Peru's income. In there he had a vision that there's only a certain amount of things that you can do to live. That there are these limits, and that the islands that we were supposed to increase the number of birds were supposed to augment the increment of excrement as he put it. There are only so many birds that could support it. And that that is a truth not just for a bunch of islands in Peru, but it is true for the world. And we humans are bumping up against that. And as to quote Paul Ehrlich, who was directly inspired by the Vogt, nature bats last. And so he wrote in 1948, the first modern world going to hell book, and all the great environmental books after that Silent Spring, Ehrlich's book, the limits to growth that Al Gore's books, they stemmed directly from him. And this is the sort of Central insight of the modern environmental movement, which is this extraordinarily powerful set of insights.

CURWOOD: Throughout this book, they're very careful Charles to maintain a neutral position, so nobody's listening. You can tell me Which side do you lean towards who's right?

MANN: I'm gonna duck your question, but least I'm gonna admit it. I'm trying to be a reporter. And even though I'm sure that most reporters, you know, Republicans or Democrats, they try to keep that out of their reporting. And the second reason, which I think is an even better one is whenever port I'm telling you, I think this is what's going on. I think I have some authority in the sense that I've researched it and, you know, this is I found out, I've talked to people. But then I start saying, what do I want? And then I'm just another guy, you know, with an opinion. And the real point of the book just takes somebody like, I hope my daughter who's now in college, and say, here are the tools you can use to form your own opinions about which way we should go in the world.

Charles C. Mann spoke to Steve Curwood at a Good Reads on Earth event at the University of Massachusetts Boston. (Photo: Jay Feinstein, Living on Earth)

CURWOOD: Alright, so you, you're taking the journalist, observer approach to all this you do throughout the market on a number of really interesting stories along these lines. But which one of these stories really grabbed you? Which one had, you know the resonance?

MANN: Well, I certainly started out as a prophet When I was 12, I read the population bomb. And it scared the pants off me. And I was really freaked out about it because that book and especially the first edition says straight up that, you know, hundreds of millions of people are going to die of famine in the next I think he said in the next 15 years, and I was 12. So that would mean before I was 27. And he laid out a very powerful and passionate case that completely convinced me. And I went to college, and I took environmental studies, and we heard much the same thing. And I was completely convinced. And then when I got to be 27, or soon thereafter, I realized that in fact, that hadn't happened, that hundreds of millions of people had not died. And it was largely because of innovations in science and technology. And I then went to work for Science as a reporter there I became a pretty committed guy and I said, Oh, everything that's was wrong science, science will save us and then I came to question that. So in a way this book was my attempt to try and resolve the matter for myself. And where I came to the conclusion, ultimately, is that if you really put the pedal to the metal ended either solution, you could think of it this way, they either both would work in their own terms, or they both represent equal leaps into the dark. And that really matters when you're choosing among them, what kind of world you want to live in. And that would be a very useful discussion for us to have, what is this future that we're trying to save?

CURWOOD: And your answer is?

MANN: Well, I don't think I can choose that for anybody. But in certain ways, I would like to combine part of both of them. So I guess part of my future would be that I was writing this book to try and get two people who hadn't talked to each other for 30 years to try to do so.

CURWOOD: So how do you get two sides to talk with each other when one side for perhaps lack of a better word has the perspective of a Wizard, and the other side has the perspective of a Prophet, the kind of prophet that says, this is not going to go so well.

MANN: I don't know if you can do this for everybody. But I think the most success I've had is when I say, Look, I don't want to change your opinion. I just want you to take the other side seriously. Take their arguments, seriously, you don't have to agree with them, but have a conversation on that basis. And that remarkably often does not happen. It's so easy to impugn bad motives on these sides and everybody does this, you know, I don't really want to engage with it so I'll say they're a corporate shill. I don't really want to say this or I'll say they're just, you know, tree huggers who want to return us to the stone age and all that sort of stuff. And I can't tell you how many times I've heard that kind of stuff. So I would think that just actually having a serious conversation would be a big step.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you, Charles man for taking this time with us today. Your new book is called The Wizard and the Prophet, two remarkable scientists and their dueling visions to shape tomorrow's world. Thank you so much for taking the time.

MANN: It was really a pleasure.

Related links:

- TED | “Charles C. Mann”

- Pacific Standard | “Two Competing Accounts ”

[MUSIC: Yo-Yo Ma & the Silk Road Ensemble (featuring Bill Frisell), “If You Shall Return” on Sing Me Home, Sony Music Entertainment]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, Candice Siyun Ji, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth