May 15, 2020

Air Date: May 15, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Stalls Clean Energy Loans

View the page for this story

Low-interest loans for clean energy could help boost the distressed economy by creating jobs, but $43 billion in loans for clean energy innovators that was set aside by the Obama Administration has barely been touched. Representative Frank Pallone Jr. (D-NJ), Chair of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, joins Host Steve Curwood to explain the holdup and how the Administration is missing an opportunity to help the jobless. (07:50)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's trip beyond the headlines, Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood examine an executive order that might threaten traditional fishing practices. Then, the pair discuss "climate-smart milk", from dairy cows that have been fed dietary supplements said to reduce the amount of methane they produce. Finally, the two look back through history to the creation of the Adirondack Park Forest Preserve, 135 years ago to help assure clean water for New York City. (03:50)

World's Largest Parrot: Note on Emerging Science

View the page for this story

A team of paleontologists in New Zealand has discovered fossils of the largest known parrot to ever exist, estimated to be about 3 feet tall and 14 pounds. Living on Earth's Don Lyman has more on the discovery of this giant extinct bird. (01:28)

Food Waste Increase in the Pandemic

View the page for this story

Long before the COVID-19 disruptions forced dairy farmers to dump swimming pool quantities of milk into fields, a third of all food produced was going to waste, with huge consequences for hunger and the climate. John Mandyck, the CEO of the Urban Green Council, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how improving distribution, consumer habits, and “best-by” labels can reduce food waste, feed the hungry, save money and reduce carbon emissions. (10:15)

Tips for Low-Waste Living

View the page for this story

Sustainable living can be as much about returning to old, thrifty traditions as it is about innovative technologies. Social media influencer Julia Watkins set out on a low-waste journey and discovered that food scraps can be repurposed in everything from soups to crackers to household cleaners. Julia Watkins is the author of the new book, “Simply Living Well: A Guide to Creating a Natural Low Waste Home” and joins Host Steve Curwood to share some of the recipes she learned along the way. (08:08)

The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis

View the page for this story

The success of the Paris Climate Agreement took the thoughtful cooperation of all nations of the world and coordination by the UN team led by Christiana Figueres. In her new book "The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis", Figueres shares her personal experience of leading the 2015 Paris talks and outlines key strategies for moving our society towards ecological responsibility. Figueres joined Host Steve Curwood at a recent “Good Reads on Earth” virtual event to discuss the urgent need to kick fossil fuels, the current pandemic crisis, and more. (15:23)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Christiana Figueres, John Mandyck, Frank Pallone Jr., Julia Watkins

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

As parts of the food chain break down in the face of the Coronavirus pandemic, lots of food is thrown away, but much more is usually wasted in US homes.

MANDYCK: Our problem is with consumers in the United States. The number one place where we waste food in the United States is at the household level. We did that before the pandemic, we're doing that during the pandemic, and we will do that after the pandemic. Food is the number one item in US landfills.

CURWOOD: The pandemic is also sounding a warning about climate inaction.

FIGUERES: As long as one person has the virus we’re all exposed in one way or the other and the same thing goes for climate. As long as there are some populations that are most vulnerable we’re all affected so it’s in our self-interest actually to act out of solidarity.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Stalls Clean Energy Loans

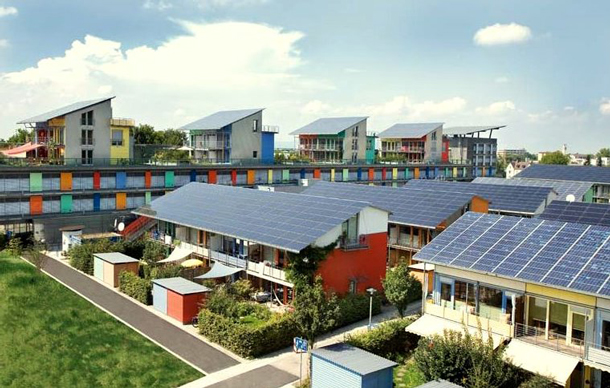

The solar energy industry is one of the fastest growing industries in the United States. (Photo: Naturalflow, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Congress and President Trump have enacted a number of measures to help prop up the economy while the coronavirus pandemic keeps millions of Americans isolated at home. Front and center is the CARES Act totaling trillions of dollars for big and small organizations as well as individuals. Months later the money has yet to arrive for many businesses and households. But the wait has been even longer for clean energy innovators who have waited for years to tap into a $43 billion low-interest loan fund that Congress and the president approved back in 2016, though it was a different president. Here to explain the holdup is Democratic Representative Frank Pallone Jr. of New Jersey, Chair of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. Congressman Pallone, welcome back to Living on Earth!

PALLONE: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So there's this perhaps $43 billion in low-interest government loans for clean energy projects, that apparently has just been sitting around waiting to be disbursed by the Trump administration. How long has this been going on? Where's it supposed to go?

PALLONE: Well, they haven't done much, if anything, with this loan program. I mean, during the previous administration, under Obama, a lot of loans went out. And the return on investment was great. It was very successful, for the most part. I think that it's probably the case that the first Energy Secretary, Perry, was not, you know, too favorable to the program. So, we're hoping that the new Energy Secretary, Brouillette, is more favorably disposed and we're talking to him about it. But it's a real opportunity with money that's already available to really stimulate the economy and do innovative energy projects that you know, would create jobs and also be helpful for the environment.

CURWOOD: Well, I was gonna say that clean energy tech jobs have been some of the fastest growing jobs in the US for a number of years now. In your view, just how could clean energy loans help the country's economy in the face of this pandemic with so many folks who are unemployed?

Clean energy advocates hope that the new US Secretary of Energy, Dan Brouillette, will be more amenable to disbursing the clean energy loan money than his predecessor, Rick Perry. (Photo: National Nuclear Security Administration, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

PALLONE: Well, I mean, you mentioned that the US clean energy sector provides more than 3 million jobs, you know, that are both energy clean, but also energy efficient. And the whole purpose of this program, Steve, is to look into innovation. In other words, you know, what kinds of projects are innovative and would utilize either existing technologies in innovative ways or be the first of the kind in a geographic region? We know that these types of things create a lot of jobs, and I think I have some statistic here that says that for the loans that went out, mostly prior to the Trump administration, less than 3% of the projects defaulted on their loans, so it has a real good record of success and supporting both businesses and jobs and of course right now because we've got, what, 30 million people filed for unemployment in the last few weeks or months because of COVID-19. I mean, something like this would be really important now in terms of creating jobs at such a high unemployment rate out there from the virus.

CURWOOD: Now, as the chair of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, what are the moves that you have now to address this issue?

PALLONE: Well, I mean, there's two things. One is to try to convince the Secretary, as I said, the new secretary Brouillette, to actually, you know, push this out. And then the second thing is to make some structural changes in the program. And the Energy and Commerce Committee that I chair has most of the jurisdiction that relates to climate change or climate action. And so we put forward a proposal called the CLEAN Future Act that has a number of initiatives to try to address climate change and make us carbon neutral by 2050. And so in that we have some structural changes to this energy program, this loan program that we're talking about today, that would, I think, improve the situation. Three things. Right now the Department of Energy has high fees that are a barrier for entry into this program. So what we do in our CLEAN Future Act is reduce expenses so that the program is accessible to more applicants. And then the second thing we have is trying to expand eligibility. This loan program has this innovation threshold, that the project has to utilize existing technology in innovative ways and be the first of its kind. So we're trying to provide more flexibility. So this idea, first of the kind isn't just like the only one nationally but maybe first of the kind in the southeast or first of the kind in New England, you know, that type of thing. And then the last thing is to have some kind of reforms for advanced technology vehicles, to expand eligibility because you know, a lot of these loans were for cars or heavy duty vehicles, you know that would refocus the program on vehicles with lower or zero carbon emissions, because that seems to be where a lot of these technological innovations are, that would be eligible for the program. If the Secretary was just willing to push out a lot of these loans, I think we could still do it without these structural changes that I'd like to see. But when we do a stimulus package, and hopefully we do a stimulus package in the next few months, we would like to see these changes that I mentioned to the program be incorporated.

Frank Pallone Jr. has served as US Representative as a Democrat for New Jersey’s 6th congressional district since 1988. He is the Chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. (Photo: US House of Representatives, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Now, some might say that these loans are going unused as a result of a partisan decision to promote the fossil fuel industry over the clean energy sector. How do you respond to that?

PALLONE: I mean, I think that's true, but I can't, you know, verify it, but I mean, as you know, the Trump administration has been much more fossil fuel oriented. They haven't really been advocates for clean energy proposals, or, you know, some of these innovative manufacturing projects for cars or trucks as well. If anything, they've been moving in the opposite direction and, you know, loosening fuel efficiency requirements, and encouraging more fossil fuels, and doing even more of that now during the COVID emergency. I would probably say you're right. But my argument to the Secretary is, look, let's do everything, right? And I'm not saying they should only do clean energy technology, as opposed to fossil fuel. But this is a program that's out there and that we think can stimulate jobs. So put aside your opposition in this environment because we need to create jobs, and don't look at it ideologically. I mean, that may be difficult. But you know, that's what I kind of do with everything right now.

CURWOOD: So, here we are in May, six months away from a national election, if the wind blows in the direction of the Democrats, what are your hopes for next year as Chair of the Committee on Energy and Commerce in the House?

PALLONE: Well, we have two things. One is to enact the CLEAN Future Act into law so that we move towards this carbon neutral goal of 2050 and reach that goal over the next few decades. And then, of course, a major infrastructure program that's oriented towards energy efficiency and clean energy. And that would include upgrading the energy grid, creating a national program for electric vehicles, and trying to do more to encourage clean energy both through incentive grants as well as tax policy. You know, there's a lot that can be done, and hopefully we have a democratic president. They're going to be much more oriented towards meeting these climate goals and putting in place programs both with you know, major infrastructure initiatives and other grants and financial incentives to achieve that. That would be the goal.

CURWOOD: Congressman Pallone is a Democrat who represents the Sixth District of New Jersey and Chairs the Committee on Energy and Commerce. Thanks so much for taking time with us today.

PALLONE: All right. Thank you, Steve. Take care.

Related links:

- The New York Times | “Billions in Clean Energy Loans Go Unused as Coronavirus Ravages Economy”

- Listen to our previous interview with Rep. Pallone (D-NJ) about the Climate Action Now bill here

[MUSIC: Tom Teasley, “Nights Over Baghdad” on All the World’s a Stage, by Tom Teasley, T2 Music]

Beyond the Headlines

A commercial fishing dock in Stonington, Connecticut. (Photo: Phoca2004, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's time now to take a look Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peters, an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. What stories do you have for us today, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Last week, President Trump signed an executive order that has both environmentalists and commercial fishermen concerned the order would pave the way for the culture operations that could threaten traditional fishers, particularly on the east coast where saltwater fish grown in pens isn't really a thing yet.

CURWOOD: Yeah, the commercial fisher people don't like this at all. They say it's gonna make a mess, right?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, there are several issues among them contamination, actually, pollution of ocean waters from fish feed contamination of the ocean ecosystem when those fish inevitably escape. Fish like tilapia that are popular in grocery stores, but that aren't a part of the East Coast ecosystem. There are big concerns already with overfishing on the East Coast, warming ocean waters, are moving traditional ranges of food fish like summer flounder, moving it from off the Carolina coast - far, far North.

CURWOOD: Well, it sounds like the notion of having fish and pens would be a major haddock for the seafood industry.

DYKSTRA: Steve that's a bad pun. This is a serious topic. And I'm not just bringing it up for the halibut.

CURWOOD: Oh my goodness. Hey, so what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: There's an intriguing story from the UK a place called Brades Farm it's a dairy operation in Lancashire is marketing what it calls climate smart milk.

CURWOOD: Oh, that would be nice. I mean, cattle, whether raised for meat, cheese or milk are considered to be climate un-smart.

It is estimated that cattle and other ruminants are responsible for about 37 percent of global methane emissions that result from human activity. (Photo: Steven Penton, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Yeah, cows' digestive systems produce a large amount of methane which enters the atmosphere via both ends of the cow but mostly through burps. Brades Farm feeds its herd a garlic supplement made in Switzerland and called, wait for the new pun, Mootral.

CURWOOD: Okay. How proven is this technology, Peter?

DYKSTRA: It's not proven yet. It hasn't caught on. If it does, it would be a big deal. As you know, methane is at least 80 times as potent a greenhouse gas as CO2. Cattle are a big contributor to the methane problem. And this would potentially solve at least a little bit of the contribution of agriculture to climate change.

CURWOOD: I'm a little skeptical of this, Peter, because in my youth, I worked on dairy farms. If the cows got into what we called onion grass, you taste it in the milk.

Lake Abanakee in the Adirondacks. (Photo: Sagesolar, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Yeah, but if this does work, it's a rare case where garlic will actually improve the breath of cattle.

CURWOOD: Okay, let's take a look back in history, Peter, and what are we going to talk about?

DYKSTRA: 135 years 135th anniversary, May 15 1885, the New York State Legislature created the Adirondack Park Forest Preserve in far upstate New York. It's a massive area about two-thirds the size of the state of Rhode Island. They wanted not only to protect a beautiful area from development, but also protect the source of the Hudson River, much of New York's water supply.

CURWOOD: And New York has fairly good water for a major metropolitan area, doesn't it?

DYKSTRA: They do. And that same year 1885, they made much of the Catskills. That's a small mountain range much closer to New York City into Catskill State Park. It's now the home of several reservoirs created to serve Metro New York and like the Adirondacks, it's home not only to beautiful scenery, some of the best biodiversity in the eastern US, but also this time of year, some of the most bodacious black flies I've ever been swarmed by.

CURWOOD: All right. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news that’a ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Food & Environment Reporting Network | “Trump’s Executive Order Seeks Controversial Overhaul of Seafood Industry”

- Fast Company | “These Garlicky Supplements Solve One of Society’s Major Medical Issues: Not Coronavirus—Cow Burps”

- More on the Adirondack Park Forest Preserve

[MUSIC: Jay Ungar and Molly Mason with Fiddle Fever, “Ashokan Farewell” on Songs Of the Civil War, by Jay Ungar, Sony Music Entertainment]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Waste not and want not. Some tips to avoid wasting food. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jay Ungar and Molly Mason with Fiddle Fever, “Ashokan Farewell” on Songs Of the Civil War, by Jay Ungar, Sony Music Entertainment]

World's Largest Parrot: Note on Emerging Science

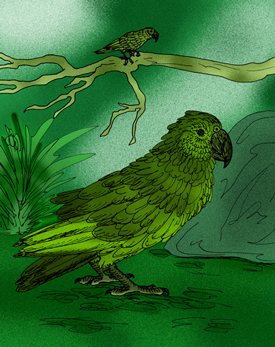

An artist’s reconstruction of Heracles inexpectatus by Dr. Brian Choo from Flinders University. (Photo: Brian Choo)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Just ahead we’ll take a look at the problem of food waste in the United States but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

This artist’s rendering compares the giant parrot, Heracles inexpectatus (below), to a similarly-extinct parrot, Nelepsittacus donmertoni (above). (Photo: Apokryltaros, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

LYMAN: Paleontologists in New Zealand have found fossils of the largest known parrot to ever exist. Researchers say the newly described species of extinct parrot, Heracles inexpectatus, would have been about 3 feet tall and 15 pounds. Scientists suspect the extinct bird probably had a massive beak that it may have used to rip open anything it liked, including other parrots. The fossilized leg bones of the giant parrot were unearthed at St. Bathans, New Zealand in 2008. Researchers thought the bones were from an extinct species of eagle. In fact, the bones sat with a collection of eagle bones for about 10 years until a graduate student realized that the fossil drumsticks were actually from a species of parrot that lived around 19 million years ago. Prior to this discovery the largest known parrot in the world was about two feet tall and around 9 pounds.

That’s the kakapo, a flightless, critically endangered parrot in New Zealand. In fact, New Zealand is a hotspot for giant birds. The island’s now extinct Moa were up to 12 feet tall and more than 500 pounds. Moas resembled their Australian cousins, emus. But until now no one had ever found an extinct giant parrot. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related link:

National Geographic | “This Toddler-Size Parrot Was A Prehistoric Oddity”

Food Waste Increase in the Pandemic

Between food that goes to waste in distribution and in-home refrigerators, a third of all food produced is wasted. (Photo: Stephen Rees, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Around the world more than a one-third of all food is wasted. In less affluent countries a lot of food becomes spoiled on the way to market, but in the US and other rich economies most food is thrown out at home because it’s rotted in the fridge or on the counter. And the numbers are huge. On a yearly basis food waste accounts for more than 3 gigatons of carbon dioxide, about a third of the human CO2 contribution to climate disruption. And with the closure of many restaurants and schools amid the pandemic, interruptions in food supply chains have led to even more food waste. John Mandyck is CEO of the Urban Green Council and co-author of the book Food Foolish: The Hidden Connection Between Food Waste, Hunger, and Climate Change. He joins me now. John Mandyck, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MANDYCK: Hey, Steve, it's great to be back on the program.

CURWOOD: Wonderful to have you. We're seeing reports that say gallons of milk are being dumped and fields and fields of vegetables are being plowed under. What's going on?

MANDYCK: You know, Steve, when I see farmers having to dump milk or plow under vegetables, I think about three big things. First thing I think about is that this shows the short term balance in our food supply. Disruption travels very fast. Think about the egg that was served in the restaurant. That egg got to that restaurant just one or two days ago. If the restaurant closes, the chicken doesn't know that. The eggs keep rolling. And so the farmer is left with a problem that he has to deal with. And so that's what we're seeing with the short term balance in our food supply. The second thing I think about is the lack of refrigerated storage for food banks. This has always been the case-- it's always been a problem. If food banks had proper refrigerated storage, all this milk that's being dumped under could have gone somewhere. And that's the plight that the farmer--has farmers say, I wish I had someplace I could deliver this milk. And the third thing this points out is that we're actually pointing the finger in the wrong place.

CURWOOD: Oh?

In the United States, most food waste happens right in our own refrigerators. (Photo: chinwei, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MANDYCK: You know, our food production and distribution in the United States is very well calibrated. Our problem is with consumers in the United States. The number one place we waste food in the United States is at the household level. We did that before the pandemic. We're doing that during the pandemic and we will do that after the pandemic. Food is the number one item in US landfills. That didn't come from the farmer --that came from our waste bins.

CURWOOD: One of the interesting aspects of the COVID crisis and the isolation associated with it is that I think more of us are cooking. To what extent do you think cooking at home will raise awareness for people about how much food has been historically wasted at home?

MANDYCK: I think it will. I mean that the closer we can become connected to our food, the better we'll understand it. You know, for a long time, we've thought that grocery stores were these magical places where, you know, we buy yogurt, we don't use it, we throw it away, we go back to the grocery store, and guess what the yogurt is back on the shelf like it magically appeared. And so we bought it again. You know, the pandemic is showing us with shortness of supply chains that well maybe grocery stores aren't the magic places that we thought they were because by the way, the yogurt wasn't there when you went back. And so hopefully it is bringing people closer to their food, starting to question, Well, why wasn't the yogurt there? Well, there's a long distribution chain to get the yogurt there. And so the closer we come to our food, I think the more respect we'll have for where it came from, how it got to our table and how we actually should cherish it more.

Food banks have limited refrigerator space, so excess milk, eggs or other highly perishable foods must often be disposed of rather than distributed to hungry families. (Photo: Staffs Live, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what about the whole notion put by more people, I don't know how many more, are gardening out there? And it's harder to throw away that lettuce that you've grown with weeding all the stuff you have to do, as opposed to just simply having picked it up at the store. To what extent do you think that making food closer to home might help with this food waste problem?

MANDYCK: I think it does. If you invest the time to grow your own food in the backyard, you literally have sweat and tears invested in your food supply. So I think that helps, but it points out another issue. I don't know if you've ever tried to grow zucchini in your backyard. The zucchini comes in and on and off switch. And so you wait all season and then you get two bushels of them.

CURWOOD: Yeah, some of them are the size of baseball bats as well if you're not careful.

John Mandyck is the CEO of the Urban Green Council and author of Food Foolish: The Hidden Connection Between Food Waste, Hunger and Climate Change. (Photo: courtesy of John Mandyck)

MANDYCK: That's right. And so I know in my house, we can't eat all of those. So it really underscores the issue in our food system, is that there's literally a bounty of riches when the harvest comes and so you have to find a way to get rid of that zucchini. Otherwise you're gonna throw it away, too, right? So you're making zucchini cakes, you're shredding it, you're freezing it. There's only so much that you can do and then you start your own food distribution system by giving it to your sister, your mother, your neighbor. But that too helps underscore the bigger picture that we have with our global food supply.

CURWOOD: So what do you recommend that we do as a nation and as individuals to reduce food waste then?

MANDYCK: Well, you know, as a nation, our number one issue is at the consumer level. That's where we're throwing away most food. It's the same in Europe, it's the same United States, it's really a rich country dilemma because we can afford to do it. Food is relatively inexpensive in the United States. And if we throw away the 99 cent yogurt because we were confused about the date label, we simply go back and get another 99 cent yogurt. So we have to have consumer education and awareness to understand the scale and consequences of what happens when we throw away that food. We have to have public policies that encourage us not to do that. And that means encouraging date labels that are rational and makes sense. This has happened in Europe. There's been strong campaigns over the last decade to encourage consumers to waste less food. And we've seen that those have worked. We need those campaigns in the United States. If you look globally, though, two thirds of all the global food supply is lost at that production and distribution level. This is an emerging economy problem where food rots in poor transportation networks, it rots in open air markets, it rots in wet markets in China, which is relevant to the pandemic that we're having today. And so we have to find ways to modernize that production and distribution system in emerging economies if we really want to tackle the issue on a global level.

Self-isolation has many of us growing vegetables, cooking more and getting a little more in touch with our food. (Photo: normanack, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what can we learn from other countries that have tried to tackle food waste?

MANDYCK: I'll point to two. In the United Kingdom, they started a consumer campaign called Love Food Hate Waste, where environmental organizations and hunger organizations partnered with the grocery stores, and the campaign has gone well. Over the last decade, they tell us that they've reduced household waste by 20%, which is a huge improvement. So that works well. France is a good case study in a different direction. A few years ago, France passed a law that bans supermarkets from throwing away food that is otherwise good to eat. Now, that sounds like a great policy that that sounds like it makes a lot of sense. But we can actually learn a lot from the French law. What happened is the supermarket said, okay, we can't throw away the food, we'll deliver him to the food banks. So if you run a small food bank in a small French village, one morning, you come to work and you could have three boxes of apples. That's great. You're going to distribute three boxes of apples to those in your village that you know they need them. The next morning, you come to work you find you have a truckload of eggs. What are you going to do with a truckload of eggs? You don't have the refrigerated capacity that we talked about. You don't have the distribution system, you can't get them out fast enough. So what happened in a inverse way is that food banks were starting to throw away the food. And, you know, kind of standing up and saying what just happened here? And so it's really questioned the role of policy policies needed. But we have to understand the unintended consequences of those policies. And the French law was, as has been a great lesson to the world.

The strawberry that molds in your fridge carries an additional carbon load from all the transport, refrigeration, and packaging it took to get from the field to your home. (Photo: Kevin Payravi, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: What's the impact of all this food waste on our climate do you think?

MANDYCK: Well food waste is, to me one of the sleeping giants of climate change. If you measure the carbon footprint of all the food that we lose or throw away each year, and we measure it as a country, it would be the world's third largest emitter of greenhouse gases. And so we need consumers to understand that particularly in the United States to help change consumer behavior that when we throw an item in the landfill, we just threw a ton of carbon in the landfill. An example is a strawberry. Steve, you and I are on the East Coast right now. If we eat a strawberry today, it came to us from California. It took a lot of carbon to prepare to grow that strawberry. The farmer had to go out in the field with a tractor. He had to plow the field under, he had to plant the strawberry, he had to water the strawberry, use a lot of water. Then he had to harvest a strawberry. Using carbon he had to bring the strawberry from the field into a packaging place which burned electricity. We took plastic which is carbon based and wrapped it in plastic then we put it on a truck and we brought it across the United States burning carbon. It got to the your grocery store, it sat on the shelf, the store is burning carbon waiting for you to come. Maybe you got in your car and burn carbon to go get the strawberry, brought it back you put it in your refrigerator which is plugged in burning carbon and then you forgot to eat it and it went bad and it got moldy and you threw it away. It would have been better to throw the strawberry away in the field from the carbon standpoint because it was fully carbon loaded when it got to you the consumer. And so we need to understand that it's not just throwing away the strawberry. It's throwing away all the carbon that went into getting the strawberry to you and to me.

CURWOOD: John Mandyck is CEO of the Urban Green Council. He's also co author of the book Food Foolish: The Hidden Connection Between Food Waste, Hunger and Climate Change. Thanks so much, John, for taking the time with us today.

MANDYCK: Steve, it's been great to be on the show.

Related links:

- NYTimes | “Dumped Milk, Smashed Eggs, Plowed Vegetables: Food Waste of the Pandemic”

- About the Urban Green Council

- About John Mandyck

- About the book Food Foolish

[MUSIC: The Blind Boys Of Alabama, “Jesus Gonna Be Here” on Spirit Of the Century, by Tom Waits, Real World Records]

Tips for Low-Waste Living

In Simply Living Well, Julia shares waste-reducing recipes, as well as instructions on how to make your own natural cleaning supplies and wellness products. (Photo: Courtesy of Julia Watkins)

CURWOOD: When Julia Watkins started thinking about food waste in her own home she took action to reduce her household waste and live more simply. She shares pictures of her low waste journey on Instagram and has amassed nearly a quarter of a million followers. And as a social media influencer she is now sharing some of her strategies and recipes in a new book, Simply Living Well: A Guide to Creating a Natural Low Waste Home. She joins us now from near Chicago. Julia Watkins, welcome to Living on Earth.

WATKINS: Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: A lot of people I imagine are starting out are looking again at the simplicity side of having really low waste, because we can't go anywhere. So in this moment, what are a couple of things that you would point out to people who really maybe haven't thought about trying to live the low waste or zero waste level--things that they could simply do right now in their homes in apartments, given the challenges that we have?

WATKINS: So my book was actually inspired by my great grandparents' generation. A lot of my style of low waste or zero waste is very old fashion. And, you know, they all survived the Great Depression by virtue of being resource conscious. So the recipes in my book are very, they're very within anyone's reach. For example, to make a veggie stock, you use scraps from the vegetables you've used for cooking throughout the week, so you don't have to go out and buy a carton of veggie stock, and you also don't have to buy new vegetables for it. When you make nut milk, you can use any kind of nut you have. You don't throw the pulp away at the end-- you use it to make crackers, you use it to make truffles. When you eat an orange don't throw the peel away--you can put it in a jar of vinegar and let it infuse for a couple of weeks and then turn it into an all-purpose cleaner.

One of Julia’s favorite recipes is the vegetable stock she makes out of her kitchen scraps. (Photo: Julia Watkins)

CURWOOD: Or you could do what my grandmother did--make candy out of this stuff.

WATKINS: Really?

CURWOOD: Yeah, those orange rinds, those grapefruit rinds, they would candy them at the holidays.

WATKINS: I haven't try that yet, but I've wanted to. Yeah, you can use orange peels for all kinds of things.

CURWOOD: So you're really big on vegetable scraps. And in fact, you have a recipe for a soup made from vegetable scraps. So talk to me about that.

WATKINS: Yeah, when I first started going zero waste, I noticed a lot of people making this veggie scrap stock. So I tried to figure out a way to make it really delicious. And basically what I do is save veggie scraps and past-peak produce, I prepare veggies throughout the week, I wash and save stalks and peels and leaves, and then I store them in a paper bag or a mason jar in the refrigerator. And when I have about four cups worth, I make the stock. So it's not as easy as just throwing the stock in a pot with some water. You want to give it a really strong flavorful base. So just chop up a couple of onions, couple of carrots, some celery and some garlic and put a little oil in the bottom of your pot and saute them until they're tender. And then just all you have to do is add your four cups of scraps, eight cups of water, let it boil, then simmer for an hour. And that's it. That's your veggie scrap stock. You can let it cool and bottle it up in mason jars and put it in the fridge if you're going to use it that week or you can freeze it, too. It freezes for up to six months to a year.

Julia grows many of her own vegetables in a garden outside her house. (Photo: Julia Watkins)

CURWOOD: Then take me to the next step. So what do you get to use this for?

WATKINS: I use it in a lot of the recipes in the book. A lot of the recipes come from harvesting vegetables from my garden. So I use it for a carrot tomato soup. And I use it for an onion garlic soup that uses 40 cloves of garlic

CURWOOD: 40 cloves of garlic.

WATKINS: Yeah

CURWOOD: A little hot for the mouth, don't you think? No?

WATKINS: Well, you roast it and it takes a lot of the sting out. It's delicious. So I use it for that and we stir fry a lot at our house. So I'll use it for stir fries. I go through the stock pretty quickly. I usually make this every Sunday as part of my weekly rhythm.

Julia considers traditional, old-fashioned cleaning supplies to be more beautiful than the more modern plastic ones. (Photo: Julia Watkins)

CURWOOD: Julie, in your new opinion, why should we be doing this? Why should we be trying to minimize the waste that we create on the planet?

WATKINS: Well, I think there's different ways to look at it. There's sort of the environmental reason. We know that we're extracting resources faster than is sustainable. We know that populations are growing and that eventually, things could get really difficult for people. For me. I know that I care about the natural world. I've had these wonderful experiences. For me, it doesn't come so much from my head. It's not so intellectual. It's a little more from like my heart, I guess, as cheesy as that sounds, but I've had these experiences. I do think I have a connection to the natural world. And it makes me feel good to be authentic to be who I say I am. And I think I've always said I would do this, even if we weren't in the midst of a climate crisis or a coronavirus. But it really, we have all the reason to do it if it's coming from an intellectual place.

CURWOOD: How do you reach people who are so driven by the brand, the label, the chicness, the being able to, what, we're moving ahead, aren't we? We must do something that's new and modern. How do you address those folks when they can look and see that so many of the things we recommend, come from, well, a century ago?

Home Grown Herbs (Photo: Julia Watkins)

WATKINS: I think you have to make it beautiful for those people. And it is beautiful. If you look at old fashioned cleaning tools, they're not made out of bright pink plastic poles or handles, right? They're made out of beautiful wood. And the bristles are made out of horsehair and real natural fibers. They're beautifully, they're aesthetically pleasing. I think a lot of people get into zero waste and natural living because of the aesthetics. And I think that's fine. Once they're there. Just try to keep them there. You know? But I think sustainability has grown because it is beautiful. And it does appeal to people's sense of style and personal aesthetic.

CURWOOD: And what would you say to folks who are now stepping into a very difficult time economically? How does your approach to natural low waste save money?

WATKINS: Well, a lot of the the recipes use what you already have. They use things that your grandmother used to when she was strapped for cash, too. They're inspired by the idea that you can grow herbs, you can dry them, you can preserve them, and then you can use them for every area of your home.

Julia Watkins lives near Chicago. (Photo: Courtesy of Julia Watkins)

CURWOOD: What inspired you to get involved in all of this?

WATKINS: I think mine happened in a lot of different stages. So my professional background is all in environmental work. I was a Peace Corps volunteer in a tiny little village in Guinea. And I saw people literally living in direct connection with the environment. And I saw them living simply and slowly. And I was so inspired by people just making do with what they had. So I think once my first child was born, and I was home for a while, I wanted to integrate everything I've learned through my education and my experiences with my actual life. That's when I started cooking with real ingredients and real food and one thing led to another. It was like a rabbit hole and then I was making my own cleaning supplies. And then I was growing a garden and learning how to sew and learning how to knit. And for me it was very empowering. I think sometimes people think of the 1950s when they think of some of these skills, but when it's a choice, when you want to learn them, it's extremely empowering. And then a time like this, I feel resourceful. I don't feel worried about things not being on the shelves at the grocery store, because I can probably make it or get by with what I have.

CURWOOD: Julie Watkins' book is called Simply Living Well: A Guide to Creating a Natural Low Waste Home. Julia, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WATKINS: Thank you for having me. Thanks so much.

Related links:

- Julia Watkins’ Instagram Account, Simply Living Well

- Julia Watkins’ Website

- Purchase Simply Living Well: A Guide to Creating a Natural Low Waste Home

[MUSIC: Benny Goodman, “Ain’t Misbehavin’” on B.G. In HiFi, by Thomas “Fats” Waller/Harry Brooks, Blue Note Records]

CURWOOD A quick correction to last week’s program. In our segment with Harvard Law professor Richard Lazarus on the Supreme Court case Massachusetts vs EPA we mistakenly edited out a comment that noted Marbury v Madison is a foundational Supreme Court ruling.

[MUSIC: Benny Goodman, “Ain’t Misbehavin’” on B.G. In HiFi, by Thomas “Fats” Waller/Harry Brooks, Blue Note Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – The hard lessons of the Coronavirus pandemic and how they relate to climate change. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Benny Goodman, “Ain’t Misbehavin’” on B.G. In HiFi, by Thomas “Fats” Waller/Harry Brooks, Blue Note Records]

The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis

After the mostly unsuccessful COP15 climate change conference in Copenhagen in 2009, the UN Secretary General appointed Christiana Figueres as new Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, starting her first term in July 2010. (Photo: UN Climate Change, Flickr, CC By 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The Coronavirus pandemic has made it clear that the world is increasingly interconnected. But amid the tragedy of the virus a top climate diplomat says there is an opportunity to rebuild our economies in ways that are both more equitable and sustainable. Christiana Figueres was the Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change when the world came together to hash out the historic Paris Climate Agreement. And the Costa Rican diplomat recently wrote a book titled The Future we Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis. She joined us for a virtual Good Reads on Earth event to talk about her book. I started by asking her about the relationship she sees between climate disruption and the coronavirus pandemic.

FIGUERES: Oh, wow. Well, actually quite a few, quite a few lessons that we can learn from the pandemic Steve. I think we have learned very quickly and very deeply that global challenges are global that they don't ask for a passport, they don't stop at any border, due to immigration, nothing like that, right? But definitely something that should teach us the lesson that building walls is completely ridiculous in front of global challenges. The other piece that I have learned is that exceptionalism is such a myth. We are only as vulnerable as the most vulnerable person among us, among us being on the planet. As long as there's one person that has the virus, we're all exposed in one way or the other. To think that you're an exception to a global rule is ridiculous. And the same thing goes for climate as long as there are some populations and we all know which of the populations that are most vulnerable, always the bottom of the pyramid. But as long as they are affected, we're all affected. So it's in our self interest actually, to act out of solidarity.

CURWOOD: This is a big deal. But what's happened this is, in fact, I think will realign how we conduct our civilization going forward. I hope so. And reminds us of what was said back at times in the ecological environmental movement to think globally, and act locally. Exactly. Because you can point out, you know, the poorest paid among us in the United States, now where I'm speaking to you from don't have access to good healthcare can't get tested for the virus. And yet, these are the folks who are cooking the food that people might take out or packaging the groceries that might get delivered or with

FIGUERES: or delivering the packages. Yeah.

CURWOOD: Delivering the packages or, you know, working in healthcare settings where wages are again, very low, and in care facilities were that we have such a ridiculously high death rate.

FIGUERES: And hence exposing to each other, right. So exposing themselves.

CURWOOD: Exactly.

FIGUERES: So you know, the appreciation for all of those professions that we never really thought about before, it has also just skyrocketed, which is a good thing. But the final thing that I just wanted to add about lessons learned is there are many different kinds of risks. But there are some that are less or more probable, and there are others that have higher or lower impact. But the real ones that we have to take a look at are the ones that have both high probability and high impact. That is true of this virus. The same thing is true with climate Steve, right?

CURWOOD: Right.

FIGUERES: That is a high probability, high impact threat. And the quicker that we understand that and begin to respond, the less we're going to suffer. So you know, although coming from two very different sources, huge common lessons between climate and the virus.

Christiana Figueres grew up in Costa Rica. She is the daughter of Jose Figueres Ferrer, who served three times as President of Costa Rica. (Photo: UN Climate Change, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And by the way, in your book, you point out that as the permafrost melts, viruses might be released because, of course, viruses when they're frozen, they can sit around forever.

FIGUERES: Yeah, I mean, that's the other thing that the relationship between climate and health is a direct relationship because first, many of the vector borne diseases that are borne by mosquitoes, for example, such as malaria and dengue and chikungunya, all of those diseases currently are restricted to the equatorial belt because that is the temperature and water conditions humidity conditions, that those mosquitoes that bear the disease need. But as temperatures increase, those temperature and precipitation conditions will actually expand beyond the equatorial belt into much higher up in the north and in the south. Hence, we will have malaria, dengue and chikungunya in areas that have never known that disease. So that's one direct impact. And the other one is you point out is that the permafrost, such as in Siberia, that has been frozen for thousands of years, could very well hold viruses that haven't been affecting us but as it melts, we could be exposed to very unusual viruses and hence, you know, diseases that we have never even heard about. So yeah, I mean, the relationship between health and climate is a pretty close one.

CURWOOD: Indeed. I mean, just here in the United States, we see very high mortality associated with people living where the’re a lot of particulates from pollution. Now, let's talk about your book some more. You have three mindsets that you describe in it. So I'm going to ask you if you could walk us through them and why you consider they're so essential when when tackling this climate crisis. Let's start with stubborn optimism. Is that you? Are you that stubborn optimist?

FIGUERES: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. We do learn things in life. And I've actually learned that it's important to be stubborn, especially if it's for the common good, right? And and so that's where that stubbornness comes. And the optimism the combination of being stubborn and being optimistic for me, means that it's not a naive optimism. It's not, you know, a blind optimism. It's actually a very educated and informed optimism that knows exactly what the conditions are either on climate or on this virus in this case. So it's an informed optimism. But it is a choice that we make to have a constructive, determined attitude that in the face of any challenge, including the one that we have, that we collectively can get out of this, because if we start with an attitude of defeatism well, then we probably stand very little chance of succeeding. Right? You know, as as the saying goes, whether you think you're going to succeed or you think you're not going to succeed. You're probably right either way, because your thought very much determines the probability of success. And so you know, arming ourselves with the gritty determination to get through any challenge is important. And we have to be stubborn about it because we know that any challenge comes with barriers and with problems that we have to get through, we have to be gritty about it.

Pictured above: the closing ceremony of the twenty first Climate Change Conference in Paris (COP21). Christiana Figueres stands along UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, Laurent Fabius Minister of Foreign Affairs of France and President of the COP21 Conference, and Francois Hollande President of France at the time. (Photo: Mark Garten, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So stubborn optimism, and then you talk about endless abundance as another mindset that's critical here. I thought we got in trouble because we think that we have endless abundance and we can just use all the resources that's on the planet. What do you mean?

FIGUERES: Yeah, well, that one does a really cool mindset because it's a provocative one, right? And it really calls into question what do we mean by abundance and what do we mean by scarcity. The reason why we have gotten to scarcity is because we have been extracting using and wasting or just throwing aside whatever we have extracted and used once. And so that has led to a scarcity of everything a scarcity of clean water, certainly a scarcity of, of atmosphere space. But you know, it is quite impressive that given the technologies that we have now that we can actually create abundance. And here's what I mean by that there is a way of thinking that would have us, I'm going to take my piece and use it and then discard it. Or even worse, Steve, the paradigm that we have grown up with, which is the zero sum paradigm, right? I'm going to win and in order for me to win, I'm going to make you lose. That zero sum game is totally and competition, this unhelpful competition is totally against a mindset of abundance. And when we let go of that, then we understand that actually we can create an abundance that is good for all of us, and that we can all win. So for example, what We can do by cleaning the atmosphere by drawing from renewable energy sources that are completely abundant, right there is no end to how much sun rays we will be able to collect, there's no end to how much wind we will be able to collect. That is abundance. And we can bring all of this energy and all of this electricity to any part of the world. So we have to be able to think in a different form. It's not me against you, it's me and you creating together.

CURWOOD: So how do you get an abundance in thinking? Because right now, it seems to me we have a paucity of clear thinking about how you know the planet works. It's getting us into this whole climate crisis. We seem to be very short, on a critical mass of folks to respond to this crisis where we are right now. In your book, you point out, you know, hey, this is like, you know, few minutes before midnight. We’re right there. We don't make the moves in this time in this window, we have cast the die, at least for hundreds of years.

FIGUERES: Yes.

CURWOOD: For the people, and maybe the civilization that follows us.

FIGUERES: Yep. And you know, when we wrote the book just a few months ago, we were thinking that we actually had these 10 years this decade in order to make the difference with greenhouse gases. And what is really scary, Steve, is that this Corona virus is sort of like climate change in a time warp, right? All of a sudden, everything has speeded up. And just to bring these two things together, the recovery packages, obviously, governments have to deal first with health issues and security and jobs. But once they get to the recovery period beyond the immediate health crisis, they are already designing recovery packages. And those recovery packages will be trillions of dollars. Some of my friends say even up to $10 trillion. Well, here's the thing, if those $10 trillion around the world go into the fossil fuel industries and all of its derivatives, we then have cemented ourselves into a high carbon high emitting economy for decades to come. And we will totally close the door to the possibility that we have right now of reducing our emissions according to science, which is reducing the emissions to one half of what we have right now by 2030. Conversely, if those recovery packages are designed with all of the crisis in mind with the health crisis, with the climate crisis, with the oil crisis, and with the inequality crisis in mind, right? If we put our arms around all of these crises that are affecting each other, and increasing each other, if we put our arms around all of them as opposed to treating them separately in silos, and we say right, these have all collided now let's converge the solutions and let's be smart about how we are going to design and dedicate this fresh capital that is going to go into the economy. Then we have the most extraordinary opportunity to really make a difference on all of those issues. But if we don't, if we actually take one by one sequentially, we are in very, very bad shape.

The Future we Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis is a book co-authored by Tom Rivett-Carnac and Christiana Figueres. Tom Rivett-Carnac worked as the Senior Advisor to Christiana Figueres while she was Executive Secretary of the UN Convention on Climate Change. Rivett-Carnac is one of the architects of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. (Photo: Courtesy of Christiana Figueres)

CURWOOD: You have a list of things to do some action items, and we would take a fair amount of time, I think if we went through all the action items that you have in The Future Wo Choose. But the first action item, kind of a big one, you say we got to let go of fossil fuels. Stop blaming and pointing fingers but get off of carbon the way an alcoholic has to kick ethanol. How do we do this?

FIGUERES: That's such a good analogy. I never thought about that but yeah, it's a very good analogy because we are addicted by our economy, not we personally, but our economy is so addicted to that. And you know, it's interesting because when you look at the way many investments are made, the logic of investment follows very much the logic of the fossil fuel industry. And it's been a really, really tough ride for renewable energy investments to have the access to the capital that they need, because they have a very different economic structure. But we have to get beyond this. I don't believe in blaming the fossil fuels because honestly, look at the United States look at any industrialized country, all the economic growth that is being enjoyed today is thanks to the fossil fuels, so we shouldn't you know, now kick them in the teeth. The fact is that they were incredibly helpful to give us what we needed in the last century, but now, we don't need them anymore. Now we should be grateful to them and put them in the retirement home because that's where they belong. And any attempt to to keep those technologies alive are frankly, they're futile, because we will move beyond them. And, and they are highly irresponsible because they are being responsible for deaths, either through health crisis, or because climate change is actually causing deaths. So we have to be able to move beyond them.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you for taking all this time with us today to talk about the climate, the virus, and your book, which is titled The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis. Christiana Figueres, what's next for you? What's your next chapter now that you got this book out?

FIGUERES: Well, I don't know. Steve, because you know, honestly, now that I'm here on the Osa Peninsula with the Corcovado Park it’s pretty, pretty tempting to stay here with the howler monkeys and the scarlet macaws. And you know, it's a pretty wonderful country, what can I say? But right now, right now, I am very focused on really trying to get the best out of the virus crisis, because it is too deep a crisis to not be able to derive a silver lining out of it. And it has fast forwarded the very difficult financial choices that we would have had to make over the next 10 years anyway, but that now have to be made in the short term. So right now, that's what I'm focused on. So thank you very much for giving me an opportunity to share those thoughts. Thank you, thank you for your time. Thank you for talking about our book. And thank you just in general for being a wonderful human being.

Related links:

- Click here to learn more about Christiana Figueres and her organization Global Optimism

- Click for Christiana Figueres’ twitter

- Click here to purchase The Future We Choose

[MUSIC: Gary Burton & Julian Lage, “Out Of the Woods” on an NPR Tiny Desk Concert, by Gary Burton, NPR]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth