August 30, 2024

Air Date: August 30, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Virtual Power Plants

View the page for this story

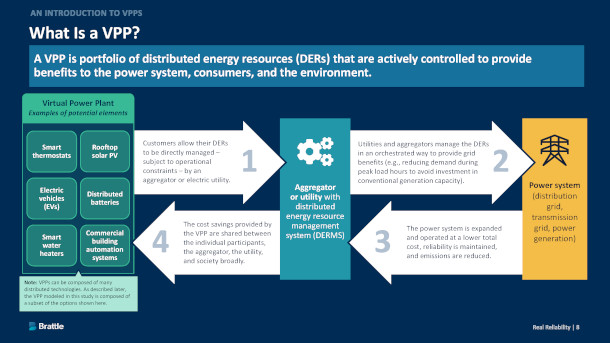

The aging grid is struggling to accommodate the surge in renewables like wind and solar. And since they don’t produce electricity around the clock, there’s often a mismatch between when the power is being generated and when it’s being used. Ryan Hledik of the consulting firm The Brattle Group explains to Host Steve Curwood how “virtual power plants” can tap home and electric vehicle batteries and shift the timing of HVAC and appliance demand to help close this gap. (11:18)

Hydrogen Fueled Future

/ Bruce GellermanView the page for this story

If you combine hydrogen from carbon-free sources and oxygen in a fuel cell, you get water and electricity. Bruce Gellerman reports on how this chemical reaction is fueling visions of future, carbon free flights and changing voyages of fantasy into reality. (12:54)

Baby Oysters Listen for Safety

/ Sophia PandelidisView the page for this story

Coral reefs play a crucial role in managing tidal surges, creating habitat for other species, and improving water quality. But many oyster species including the Australian flat oyster are under threat. So, some scientists in Australia are looking into how baby oysters find an appropriate place to set up shop. Living on Earth’s Sophia Pandelidis has more on how sound may be key. (04:39)

Science Note: Can Plants Hear?

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Flowers don’t have ears like ours, but recent research finds that some flowers, like evening primrose, can “hear” the buzzing of bees’ wings. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports on how these flowers sometimes quickly respond to nearby pollinators by sweetening their nectar. (02:11)

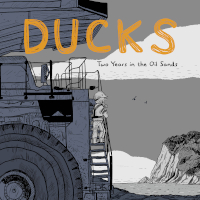

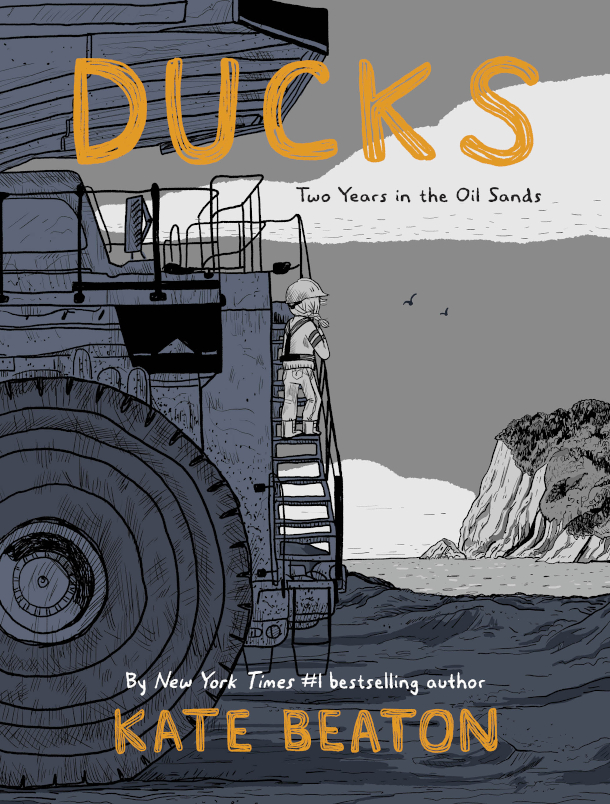

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands

View the page for this story

The Athabasca oil sands in Alberta; Canada ranks as one of the world’s most destructive crude oil operations. People laboring in the Athabasca oil sands often live in austere work camps, with long 12-hour shifts and female workers imperiled by sexual harassment and violence. Kate Beaton captured that painful reality in her 2022 graphic memoir Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands and joined Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to talk about her experience. (16:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240830 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Ryan Hledik, Kate Beaton

REPORTERS: Bruce Gellerman, Don Lyman, Sophia Pandelidis

DOERING: From PRX this is Living on Earth

(THEME)

I’m Jenni Doering.

Fixing the antiquated grid with virtual power plants using software and smart batteries.

HLEDIK: It's this idea where customers have a lot of flexibility in their demand for electricity, customers who are buying electric vehicles have the ability to change when they're charging that car to a degree. Customers with smart thermostats can manage the thermostat in a way that changes when they're cooling their home. (0:18)

DOERING Also, big hopes for powering the world with the tiniest element.

BELT: Because of advances in renewable energy, because of the advances in electrolysis technologies, it’s absolutely feasible to see that within 10 years that we could have a massive piece of the energy infrastructure based on green hydrogen. (16)

DOERING: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Virtual Power Plants

VPPs are networks of small energy-producing and storage devices, such as solar panels and batteries, that are pooled together to serve the electricity grid. (Photo: Hiro Yamagata, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering. Electric vehicles aren’t just useful for getting you and me from Point A to Point B.

With smart policies they could also help decarbonize the grid. That’s because renewables like wind and solar don’t produce electricity around the clock.

So there’s often a mismatch between when the power is being generated and when it’s being used.

And until it’s needed the big batteries in electric cars and trucks can help store some of that precious power. That’s part of the strategy called “virtual power plants.” A 2023 report by the consulting firm The Brattle Group estimates that virtual power plants could save utilities and their customers as much as $35 billion over the next decade. Ryan Hledik is a Principal at The Brattle Group and joined Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: So what exactly is a virtual power plant? Please explain how they would operate.

HLEDIK: So a virtual power plant is basically a collection of customers, it could be residential households, it could be commercial buildings who have been recruited into a program and are participating in that program and being provided incentives to participate in order to provide some of these services to the grid. It's basically this idea where customers have a lot of flexibility in their demand for electricity. Customers who are buying electric vehicles have the ability to change when they're charging that car to a degree, customers with smart thermostats can manage the thermostat in a way that changes when they're cooling their home. So one example of this could be if you're a customer who had made an investment in a battery at your home, because you wanted to use that battery as a form of backup power during an outage, you could be paid by your local utility or another company to actually allow them to control that battery on a limited number of days per year, limited number of hours per day, to provide services to the grid from the battery. By doing this, the really interesting opportunity that we're seeing here is, first of all, it's a way to directly pay customers to participate in the decarbonisation transition. And then in addition to that, instead of going out and building a gas peaker plant that might only be used 100 hours per year, we're able to tap into an investment that's already been made for other reasons that customers battery, and get more use out of that to provide more of a benefit to the power grid and to society more broadly.

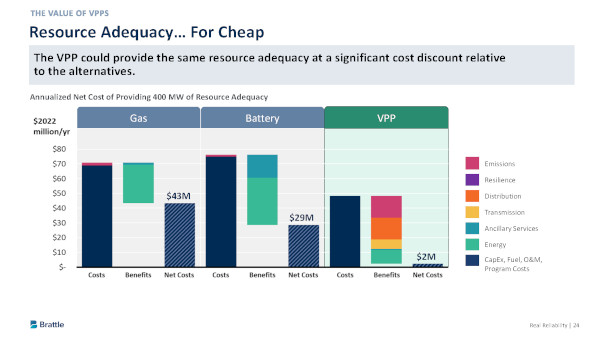

Graph from Brattle Group pointing to costs and savings from virtual power plants. (Photo: Courtesy of The Brattle Group)

CURWOOD: What role do electric cars play in the world of virtual power plants? They have pretty sizable batteries in them.

HLEDIK: Electric cars have sizable batteries, and they're a pretty large discretionary source of flexible electricity demand. So there's a lot of excitement about the potential for electric vehicles to participate in virtual power plant programs, projections that I've seen forecasted that, based on what we're likely to see in terms of electric vehicle adoption, over the course of the next decade, we could have dramatically more energy storage connected to the power grid in the form of electric vehicles and batteries on wheels, then we will see in terms of large utility scale batteries being deployed onto the power grid. So the idea with incorporating electric vehicles into a virtual power plant is that by encouraging customers to shift their charging to those off-peak hours in the middle of the night, when demand is low, or even in the middle of the day, when maybe there's solar power that's being curtailed, because you have more than you need, you can shift the charging load of the EVS into those hours to provide benefits that you otherwise wouldn't have if the customers were to just simply drive home from work and plug their electric vehicle into the wall when they got home.

CURWOOD: But what if somebody wants to get in that car right now and then wants to drive the 200 miles to Aunt Thelmas because she called saying she has an issue?

Graph from the Brattle Group explaining the virtual power plants. (Photo: Courtesy of The Brattle Group)

HLEDIK: That's right and one of the important characteristics of virtual power plant programs is they are designed with constraints on how they'll be used to make sure that customer comfort and convenience is maintained. So in the case of an electric vehicle, virtual power plant, you could have a program designed such that customers are always ensured that even if their utility is going to manage how that vehicle is charging overnight, that they will be starting the next day at 6am with a full state of charge in their EV. So those parameters, those rules are built into the program to make sure that they align with customer needs and customer convenience.

CURWOOD: What kind of money could we save in this country if we use virtual power plants rather than trying to just expand the traditional grid infrastructure?

HLEDIK: We looked into the answer to that question in our study and what we found was if we reached a pretty significant but achievable level of virtual power plant deployment by 2030, we could save 15 to $35 billion over the ensuing decade, relative to if we were to make investments and those more conventional gas peakers and utility scale batteries.

CURWOOD: So right now, the burning of fossil fuels in this country is linked to some 300,000 excess deaths a year. What are some of the co-benefits of dealing with the greenhouse gas problem using virtual power plants?

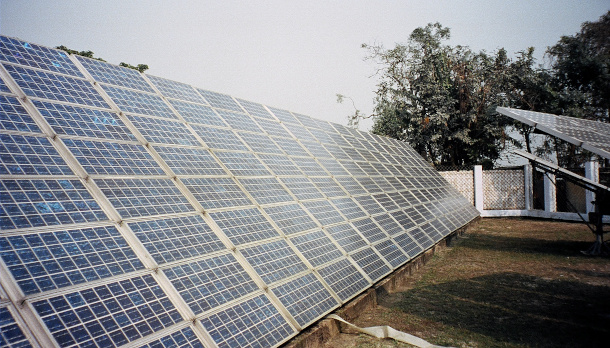

A virtual battery is like a piggy bank that allows you to store the surplus from your solar panels and convert it into a financial discount on your electricity bills. (Photo: Stephan Ridgway, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

HLEDIK: In our study, we did look at the societal benefits associated with reduced greenhouse gas emissions that would come from the virtual power plant that we modeled. And we estimated that over that same 10 year period, at the level of deployment that I described, there can be an additional $20 billion of benefits associated with improved health and avoiding other detrimental effects that are associated with carbon emissions.

CURWOOD: Let's go back to electric cars for a moment. One of the strange things about electricity is that when you make it, it vanishes unless you figure out some way to store it. But the big old base power plants like nuclear plants, which is I think it's what 20% of the electricity in this country right now or the coal fired power plants, the middle of the night, they're cranking out electricity that's not being used that's just going away, just being wasted. It just disappears, it dissipates unless it's stored somehow. How can the virtual power plant notion take advantage of that? If this could be used to soak up some of that energy that otherwise would go to waste? I mean, charging cars, the middle the night is an obvious one but what are some of the other ways that we could take advantage of that baseload that right now goes to waste?

HLEDIK: It's interesting, and California has, and parts of the Southwest have seen this issue pretty acutely. And those are areas of the US where there's been a lot of solar generation that has been built over the course of the last several years. And so on a mild day, when there's not a lot of demand for electricity in the middle of the day, what we're seeing is there can be times when the sun is shining, when there's a lot of generation, actually, you have baseload generation, and then you have a lot of generation coming from the solar panels that can't be consumed for the reasons that you just described, supply exceeds demand. So providing customers with an incentive to shift their electric vehicle charging load into those hours is one opportunity. But another example would be if customers were to pre cool their homes during that midday period, so that they didn't need to run their air conditioners as much during the evening period. That's one way to shift some of their electricity consumption to the middle of the day. Another option that we've seen, that has been very effective, has been for customers with electric water heaters to use the electric water heater, essentially as a thermal battery, and to use the storage tank of that water heater to heat the water when it makes sense when the sun is shining, when there's more electricity than you need on the system. And then as long as the tank has hot water in it when the customer needs to take their shower, then the customer can take their shower without even noticing any difference in this service that they've received what are called smart water heaters or grid-interactive electric water heaters are a really useful resource for tapping into that type of potential.

Ryan Hledik is a Principal of the Brattle Group. Mr. Hledik specializes in regulatory and planning matters related to the emergence of distributed energy technologies. (Photo: Courtesy of Ryan Hledik)

CURWOOD: You know, it's interesting, this notion of say pre-cooling a home, it goes against conventional wisdom, people would think well, I don't want to leave the air conditioning on all day when I'm not there. When I come home is when I want to be cool. But virtual power plant thinking inverts that, huh?

HLEDIK: It inverts that and again provides customers with the financial incentive to do something that's good for the power grid and ultimately helps us achieve our decarbonisation goals. One state that you might not immediately think of that has a really interesting program is Vermont and the utility Green Mountain Power in Vermont, where the utility is providing customers with subsidized batteries that the customers get to install in their homes, the customers benefit from having that battery available as a form of backup power. But in return for receiving that heavily discounted battery from the utility, the utility gets to manage that battery during certain days of the year to provide benefits to the power grid. And it's a really interesting kind of win, win situation because the customer gets that resilience benefit, the utility is able to reduce costs on the power grid and keep the power grid reliable. And then on top of that Green Mountain Power is focusing on deploying these batteries in locations of their grid that have lower than average reliability, and where there are customers with lower than average incomes. So it's a great way to provide a lot of benefits in a lot of different ways through a single virtual power plant program.

CURWOOD: All right, well, let's cut to the chase here. This seems like a almost a no brainer idea to move into the area of virtual power plants. What's standing in the way? What are some of the barriers we're seeing when it comes to expanding virtual power plants?

HLEDIK: Well, right now, utilities don't have a strong incentive to adopt virtual power plants. The way utilities make money is by earning a return on capital investment in conventional power grid infrastructure. Poles and wires and power plants. Utilities don't have that same profit opportunity if instead they're using that money to pay customers to reduce their electricity demand. So where I'm hoping we're going to see innovation is around changing the utility regulatory model in a way that provides utilities with an incentive financially to go out and pursue virtual power plants. The other thing that I think is interesting to note here is electrification of transportation and heating is a real opportunity for electric utilities. Not only to be part of the decarbonisation transition and a central player in that, but also it's an opportunity for them to go out and build out power systems and earn a return on those investments to make sure that electrification is happening. And so in that sense, virtual power plants are going to become an enabler for utilities to go out and deploy more capital because it will be part of the agreement with the regulators to do that.

DOERING: That’s Ryan Hledik, a Principal at the Brattle Group speaking with Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Brattle Group study on virtual power plants.

- Learn more about Ryan Hledik

[MUSIC: Offthewally, “Tremellow” on Surfari, Jake Haris]

DOERING: Just ahead – the tiniest element in the universe is generating energy and new technologies.

Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, “UFO Tofu” on UFO Tofu, by Bela Fleck, Warner Records/Sony Music Entertainment]

Hydrogen Fueled Future

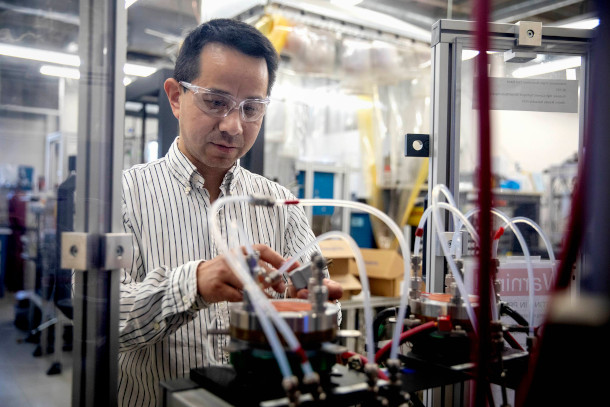

These electrolysers from Giner, Inc split the bonds of water to produce hydrogen and oxygen. (Photo: Robin Lubbock, WBUR)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

Hydrogen is Atomic Number 1 on the periodic table because it’s the smallest, lightest element in the universe. It’s also by far the most abundant, making up about three-quarters of all matter.

And if you take hydrogen derived with carbon-free energy and combine it with oxygen in a fuel cell, you get water and clean, green electricity.

This chemical reaction is fueling visions of zero-carbon flights and voyages that could one day become reality. Our friend Bruce Gellerman first produced this story for WBUR-Boston.

GELLERMAN: 150 years ago, Jules Verne captured the world's imagination with his science fiction novel, “Mysterious Island”, continuing the journey of the Nautilus submarine.

CAPTAIN NEMO: I'm Captain Nemo. Welcome to my island.

[“MYSTERIOUS ISLAND” MUSIC]

GELLERMAN: Verne wrote that "water will one day be employed as fuel," that the separated elements, hydrogen and oxygen, quote, "will furnish an inexhaustible source of heat and light, of an intensity of which coal is not capable.” Pure hydrogen is a powerful energy source and it is the most abundant element in the universe. And over the decades, the dream of harnessing hydrogen to transform the world's economy has persisted in the hearts and minds of scientists and politicians.

SOVACOOL: And the term in the communications studies literature and psychology is, "they came to a symbolic convergence.”

GELLERMAN: Benjamin Sovacool, Director of Boston University's Institute for Sustainable Energy, is author of the book: "Visions of Energy Futures.”

SOVACOOL: Symbols, ideology, values and language all coalesced around this miraculous vision of what a hydrogen economy would do, and the fantasy itself was very very real, and it was very effective at shaping funding patterns, and at shaping even scientific discourse.

GELLERMAN: Sovacool recalls President George W Bush's 2003 State of the Union Address.

BUSH: Tonight I am proposing 1.2 billion in research funding, so that America can lead the world in developing clean hydrogen-powered automobiles.

[APPLAUSE SFX]

SOVACOOL: Whenever anyone talks about a hydrogen economy, they’ll usually say things like, "well, and its only output is water."

[APPLAUSE SFX]

BUSH: A simple chemical reaction between hydrogen and oxygen generates energy, which can be used to power a car, producing only water, not exhaust fumes.

While most of the hydrogen produced today uses fossil fuels, green hydrogen uses renewable energy sources. (Photo: Robin Lubbock, WBUR)

GELLERMAN: Chances are you're not driving a hydrogen-powered car, at least not yet.

There are several good reasons. On earth, most hydrogen is chemically bonded to oxygen to form water or to carbon to make fossil fuels. And the procedure most often used emits a lot of climate disrupting gases. Sovacool says scientists have color-coded hydrogen according to the kinds of energy used in the separation process.

SOVACOOL: So there’s gray and black, which is fossil fuel, there’s blue which comes from natural gas, there’s green which comes from renewables, and there’s pink which comes from nuclear power.

GELLERMAN: Today, most of the hydrogen we separate today is black. Green is the kind you want, using electricity generated by renewable solar and wind power. But until recently, it wasn't practical or profitable to make large amounts of green hydrogen.

Scientists at the Massachusetts-based R&D company, Giner Inc, have been working at it for 50 years.

BELT: We operate at the frontiers of electrochemical technologies, pushing the envelope. We're actually the best in the world at that.

GELLERMAN: Andy Belt is Giner's CEO. He says the company has been perfecting the technology to split water efficiently. It's a process known as electrolysis. It's done in a device called an electrolyser.

BELT: In the guts of the electrolyser, where the magic happens, you combine water with electricity, and you break the bonds of water and out comes hydrogen and oxygen. And that's the magic that goes on in the center of an electrolyser.

GELLERMAN: Inside the devices are thin membranes, coated with precious metals. They enable the electrochemistry magic to work. Low cost wind and solar electricity make the process green.

BELT: Because of advances in renewable energy, because of the advances in electrolysis technologies, it’s absolutely feasible to see that within 10 years that we could have a massive piece of the energy infrastructure based on green hydrogen.

Andy Belt, CEO of Giner, Inc, says that the cost of producing green hydrogen is declining. (Photo: Robin Lubbock, WBUR)

GELLERMAN: Belt says producing green hydrogen is becoming more cost effective as the price of generating electricity from solar and wind declines. Today, in many places the renewable energies are cheaper than burning natural gas and coal.

BELT: So if I can buy electricity at 2 cents per kilowatt hour and make hydrogen with my electrolyzer, the cost of electricity to make a kilogram of hydrogen is now a buck or less.

GELLERMAN: And that's one of the Department of Energy's goals. Cut the cost of separating hydrogen by 80 percent in a decade. It would make the price of energy from hydrogen equal to gas selling at about a dollar a gallon. Boston University's Benjamin Sovacool says that price doesn’t even consider the hidden costs of burning fossil fuels on the climate and human health.

SOVACOOL: You start pricing coal accurately, hydrogen’s much more competitive. You start pricing things like oil more competitively, hydrogen and renewables are more competitive. Energy’s cost does not match its price.

GELLERMAN: Sovacool still has doubts about the future of a green hydrogen economy, but he's cautiously hopeful the proposed federal hydrogen hub program could work.

SOVACOOL: I'm slightly skeptical, but I think there's a lot more rationality for hydrogen here. If the government were to continue to create the right policy architecture, hydrogen transitions could very much occur in the next 10 or 15 years. They won't happen by themselves in the market, but if they had the right sort of incentives and policy, I could see it happening.

Bill Spellane is Chief Operating Officer of Alakai Technologies, a company hoping to make hydrogen-powered air travel a reality. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman, WBUR)

GELLERMAN: It’s already happening in Massachusetts, where engineers with Alakai Technology are unlocking hydrogen’s power.

[HANGER SFX]

GELLERMAN: In a large hanger at Minute Man Air Field in Stow, Mass workers are assembling prototypes of clean green, flying machines unlike any that have flown before.

SPELLANE: So we’re building a hexacopter that will fly up to 400 miles, a thousand pounds of people or cargo, we’re hydrogen powered, not battery powered. We do hydrogen.

GELLERMAN: Bill Spellane is Chief Operating Officer of Alakai Technologies. He's standing under one of the six rotor blades of the company's Skai aircraft, spelled S-K-A-I. The hydrogen-electric hexicopter looks like a futuristic minivan that can take off and land vertically.

Aboard SKAI will be cyclinders filled with liquid hydrogen that's warmed to a gas and pumped into fuel cells, where the hydrogen will combine with oxygen from the atmosphere, producing H2O and electricity.

There are no fossil fuels, no climate disrupting emissions.

SPELLANE: Hydrogen plus oxygen equals water and energy. We use the energy, expel the water. That’s our emissions, water.

GELLERMAN: That’s it?

SPELLANE: That’s it, water.

GELLERMAN: Hydrogen packs a powerful energy punch, pound for pound, gallon for gallon. Three times more energy than jet fuel. And refueling takes just a few minutes.

SPELLANE: For an aviation application, hydrogen is compelling. You need to store a lot of fuel in order to fly a vehicle. Hydrogen provides that to you. We have fewer moving parts, the vehicle is simple to operate, simple to maintain. You don’t have to pay as much in maintenance.

GELLERMAN: Spellane says the hexacopter is stable in high winds, has room for a pilot and 4 passengers, can be used for air taxi and cargo services, medical flights, and disaster relief. Top speed? 115 miles per hour. Rotors mounted on the 6 arms, stretch skyward, each powered by an electric engine.

SPELLANE: If you want to tilt forward, the rotors in the back speed up, the ones in the front speed down, your attitude changes, and now you can fly forward. If you want to go right, you speed up the left side, turn down the right side, you roll right.

[RADIATOR FAN SFX]

GELLERMAN: Technicians test a radiator fan aboard one of three SKAI prototypes. Today 50 engineers, many ex-military aviators and engineers, work at Alakai.

Bill Spellane, speaking with an understated passion, says he’s worked 7 days a week for the last 5 years.

Alakai Technologies’ hexacopter is powered by hydrogen fuel cells, which emit only water. (Photo: Tamara Willsie)

SPELLANE: This is the second vehicle ever built, R&D vehicle. Pure iron bird test vehicle.

GELLERMAN: Do you have a name for it?

SPELLANE: We call it Prototype 0.5.

GELLERMAN: No endearing term, no like Bluebird 7, or something like that, or Hydro 3?

SPELLANE: We are engineers, sir. Prototype 2.

GELLERMAN: Spellane hopes a public demonstration of the hydrogen-powered hexicopter takes place soon. Then, he predicts, things are going to take off. But actually, hydrogen fuel cells have been around for 60 years, when a breakthrough launched the technology into orbit, literally.

BELT: And that was a technology developed by GE in Lynn, Massachusetts, for the Gemini space program..

GELLERMAN: Andy Belt, head of the hydrogen research company Giner, says back then, General Electric engineered fuel cells that were reliable, powerful and safe for space, and beyond.

BELT: That was extraordinarily exciting. Fuel cells, hydrogen, were going to be the future of not just of space travel, but transportation in general.

GELLERMAN: But so far hydrogen hasn't fueled our general transportation needs. It may be the most abundant element in the universe, but isolating hydrogen has been expensive and climate disruptive. Clean renewable sources of electricity could change the equation. Large solar and wind projects may make it possible to power electrolysis to split water and produce green hydrogen on an industrial scale. Judith Lattimer, a senior project scientist at Giner, looks to the horizon for a way to make hydrogen low cost and climate friendly.

LATTIMER: What we’re working on is to couple offshore wind turbines directly with electrolyzers, in order to produce hydrogen offshore for fueling ships, or you can use a pipeline to get it on shore.

GELLERMAN: Either way would be a sea change. In fact, “Sea Change “ is the name of a green hydrogen powered ship.

RATTI: We are turning hydrogen into electrons, into electricity, through a fuel cell, without the carbon, which is kind of incredible.

GELLERMAN: Pace Ratti is founder and CEO of Switch Maritime, developer of Sea Change. The 70 foot vessel, powered by hydrogen fuel cells, is ferrying passengers across San Francisco Bay. Ratti has spoken with other seafaring companies. He won’t discuss specific deals, but suggests they're in the works here.

RATTI: There’s going to be a lot of exciting projects on the east coast.

GELLERMAN: The green hydrogen economy, powered by solar and wind energy, is picking up speed as a replacement for fossil fuels. And Pace Ratti says the developments haven’t gone unnoticed.

RATTI: Traditional oil and gas companies are trying getting into this game as well, you know, seeing hydrogen as the next commodity they want to be selling in addition to or in place of oil and gas.

[CHEVRON ADVERTISEMENT MUSIC]

CHEVRON:What lies on the horizon, the answers lie beyond the roads we know.

GELLERMAN:Chevron oil advertised its hydrogen hopes on air.

CHEVRON: We recognize that energy demand is growing and the world needs lower carbon solutions to keep up.

The hexacopter can fly at up to 115 miles per hour while carrying a pilot and four passengers. (Photo: Robin Lubbock, WBUR)

GELLERMAN: Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Shell Oil have joined forces with other energy interests to develop a large-scale hydrogen hub along the US Gulf Coast.

They are competing for a chunk of the 9.5 billion dollars in hydrogen funding set aside in the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. But while big oil has big plans, building a green hydrogen economy will require tens upon thousands of small companies developing innovative products like the ship Sea Change and Alakai’s SKAI hexacopter.

[HEXICOPTER SFX]

GELLERMAN: The unique flying machine is now going through the F-A-A certification process. Watching is company COO Bill Spellane, who stands in a field as a test pilot puts the hydrogen powered vehicle through its paces.

SPELLANE: It’s quieter than a helicopter, it’s quieter than a turbine aircraft. It’s quieter than the piston aircraft that also take off at this airport. Is it something you can sleep under? No, but you be the judge of how loud it is.

[HEXICOPTER SFX]

GELLERMAN: And slowly, surely, the hydrogen powered hexacopter lifts off the ground.

For a century and a half, the green hydrogen economy has been predicted by novelists, researched by scientists, and hyped by politicians. But as the global climate crisis worsens, the technology advances. China, Saudi Arabia and Brazil are among the countries investing billions to produce green hydrogen, their ambitions generating real hope for a future imagined long ago by science fiction writer Jules Verne.

[MUSIC]

GELLERMAN: For Living on Earth, I’m Bruce Gellerman.

Related links:

- WBUR | “Moving Hydrogen from Hype to Hope”

- WBUR | “Freeing—and Capturing—Hydrogen in Mass.”

- WBUR | “Going with Hydrogen, by Land Sea or Air”

- Giner, Inc.

- Alakai Technologies website

- The Switch Maritime website

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions “Tall Journey”]

Baby Oysters Listen for Safety

It appears that oyster larvae are attracted to the sounds of a healthy reef. (Photo: Petras Gagilas, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Hydrogen powered vehicles, like EVs, can be much quieter than those that run on gas or diesel.

So a transition away from fossil fuels in cars, planes, and ships could bring relief to human ears as well as other species that are sensitive to sound.

Including some that don’t have any ears at all.

Living on Earth’s Sophia Pandelidis reports on how young oysters may use sound to find a safe place to live.

[OCEAN SOUNDS]

PANDELIDIS: For a baby Australian flat oyster, the world beneath the waves can be a scary place.

When it first leaves the safety of its parent’s shell, an oyster larva is only around 170 microns long—that’s about as thick as two sheets of paper.

And if it hopes to be one of the lucky survivors out of millions of siblings, it better find a place to settle–fast.

Scientists are uncertain about how exactly these little larvae choose which way to go.

The “sizzling bacon” sound of snapping shrimp dominates the underwater soundscape of a thriving reef. (Photo: budak, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

But it’s possible that oysters use sound to navigate.

Oysters don’t have ears, but they can still interpret and react to sound by sensing with their bodies the way that sound waves rattle particles as they move through water.

[sounds of shipping motors (Source: Freesound, Mrthenoronha)]

PANDELIDIS: It is well-known that anthropogenic noise pollution can be disruptive to marine life. The sounds of shipping motors, offshore construction,

[offshore construction (Source: Freesound, Mrthenoronha)]

PANDELIDIS: And military SONAR.

[Sonar (Source: FreeSound, Breviceps)]

PANDELIDIS: Can be disorienting and sometimes lethal for underwater organisms.

Fish also make a wide variety of sounds, ranging from “purring” to “grunting.” (Photo: Stefan David, CamperCo.de, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In fact, oysters have been shown to slow their feeding and growth rates–and even clamp their valves shut– when bombarded with these noises.

But oyster larvae have also been known to swim impressive distances towards a pleasing sound.

So, researchers at the University of Adelaide in Australia tried to find out if sound might even be a key to oyster restoration.

[snapping shrimp sound (Source: Dr. Dominic McAfee, University of Adelaide)]

PANDELIDIS: They set up a soundscape imitating a healthy reef– an ideal spot for an oyster to settle down– and played it on carefully positioned underwater speakers.

Sea urchins scrape algae off rocks with their teeth, adding yet another sound to the reef environment. (Photo: Diane Graham, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

[crackling continues]

PANDELIDIS: Snapping shrimp, which hide in the nooks and crannies of reefs, dominate this underwater orchestra.

[snapping shrimp in the clear]

PANDELIDIS: They create air bubbles that pop by snapping their claws together at roughly 60 miles per hour, making them one of the fastest moving creatures in the animal kingdom.

And while researchers say the shrimp take first chair in the underwater orchestra, other creatures add richness to the symphony.

[Fish sounds (Source: Research Paper: The sound of recovery: coral reef restoration success is detectable in the soundscape, from the Journal of Ecology, also given explicit permission and additional audio files from Dr. Timothy Lamont from the University of Exeter, lead researcher on the paper)]

PANDELIDIS: Fish that purr, grunt, whoop, and even honk make up the brass section.

Dominic McAfee, the lead researcher in the restoration project, holds one of the underwater speakers his team developed. (Photo: Dominic McAfee)

And grazing urchins, which scrape algae off rocks with their teeth, bring in the percussion.

[grazing urchins sound (Source: “Sea Urchin Grazing” on Vimeo, credit to Craig A Radford, University of Auckland, from whom I also got explicit permission)]

PANDELIDIS: Dr. Dominic McAfee, the lead researcher in the project, says his team even added non-animal elements

[Thunder sound (Source: Freesound, Simon Spiers)]

PANDELIDIS: Like lightning strikes and crashing waves to flesh out the acoustics here. And it’s worked.

McAfee and his team found that oyster recruitment increased significantly at sites near the reef-imitating speakers.

They saw 17,000 more larvae settled per square meter on boulders they placed near the speakers, as compared to settlement areas without the presence of added sound.

Many oyster species worldwide have been decimated by human activity.

And the Australian flat oysters were harvested to the point of near extinction over the last few centuries.

That’s bad news for water quality—oysters are crucial for filtering water in aquatic ecosystems.

Oysters can also form reefs that can act as natural barriers, protecting shorelines from severe storms.

So people have a vested interest in restoring a healthy oyster population.

Dr. McAfee’s students build the speaker designed to attract oyster larvae to restoration sites. (Photo: Dominic McAfee)

In Australia national restoration efforts began in 2015, and the Adelaide researchers hope to include soundscapes in future restoration work.

[continue snapping shrimp, fish sounds]

PANDELIDIS: They are optimistic that an underwater symphony will be able to attract other species as well to improve their populations and create healthy reefs.

For Living on Earth, I’m Sophia Pandelidis.

Related links:

- Journal of Applied Ecology | “Soundscape Enrichment Enhances Recruitment and Habitat Building on New Oyster Reef Restorations”

- Journal of Applied Ecology | “The Sound of Recovery: Coral Reef Restoration Success Is Detectable in the Soundscape”

[MUSIC: Joey Alexander “Draw Me Nearer” on Eclipse, Motema Music LLC]

Science Note: Can Plants Hear?

Researchers observed that when evening primrose was exposed to the sound of a flying bee, or similar (but synthetic) sound-signals, the flowers began to excrete sweeter nectar within three minutes. (Photo: TJ Gehling, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: You might be surprised to learn that some plants can also hear – well, sort of. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman has this note on emerging science.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

[SFX BUZZING OF A BEE]

LYMAN: Humans can hear the gentle buzzing of a honey bee with our ears of course, but it turns out that some flowers can also hear the sound of their favorite pollinators. Well, kind of…researchers at Tel Aviv University recently found that the concentration of sugar in the nectar of evening primrose temporarily increased within minutes of sensing vibrations from pollinators’ wings. The researchers suspect the flowers act like ears, and can pick up the specific frequencies of bees’ wings, but are able to tune out background noise, like wind.

To test their hypothesis, scientists exposed plants in the lab to five sound treatments: silence, recordings of a honeybee from four inches away, and computer generated sounds in low, intermediate and high frequencies.

Plants under sound proof glass jars – the silence group – as well as plants in the intermediate and high frequency groups,

[SFX HIGH FREQUENCY SOUND FOR 1-2 SECONDS HERE]

had no significant increase in sugar concentration in their nectar.

But plants exposed to recordings of bee sounds

[BUZZING FOR 1-2 SECONDS]

and similar low-frequency sounds

[LOW FREQUENCY SOUND 1-2 SECONDS]

produced as much as 65 percent more sugar in their nectar within three minutes of exposure to the recordings.

The researchers believe that sweeter nectar may attract more pollinators and increase the chance that bee detecting evening primrose will cross-pollinate with other plants and pass on their bee hearing genes.

Evening primrose and other plants “hear” due to how their petals vibrate when sound waves pass them by. (Photo: U.S. Forest Service, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The researchers also conducted experiments that showed that the bowl-shaped flowers of the primrose picked up and amplified sound vibrations.

This single study has opened up a new field of scientific research, which the researchers call phytoacoustics.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related links:

- Smithsonian Magazine | “Flowers Sweeten Up When They Sense Bees Buzzing”

- Read the original article published in bioRxiv here

DOERING: Just ahead, a firsthand account of the perils of working in the Canadian oil sands.

Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands

The cover of Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands. (Image: copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

The Athabasca oil sands in Alberta, Canada have been called the world’s most destructive oil operation because it involves razing the boreal forest and then strip mining the oil-rich sands underneath. And a 2023 study from the government of Canada found that the greenhouse gas emissions from tar sands may be at least 65 percent higher than those reported by industry. In addition to these environmental and climate harms, the extraction of these fossil fuels has also taken an emotional toll on some of the people who work in the industry. They typically live in austere work camps and rotate through 12-hour shifts both day and night, in temperatures frequently below zero degrees Fahrenheit. And for the women who have sought employment in the male-dominated oil sands, the job can bring unwanted comments and sexual violence. That’s a painful reality captured in the 2022 graphic memoir “Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands” by cartoonist Kate Beaton. Please be advised that we will discuss sexual assault in this segment. Kate Beaton joins me now from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Welcome to Living on Earth, Kate!

BEATON: Thank you.

DOERING: So can you tell our listeners the story behind the title and explain why you chose it?

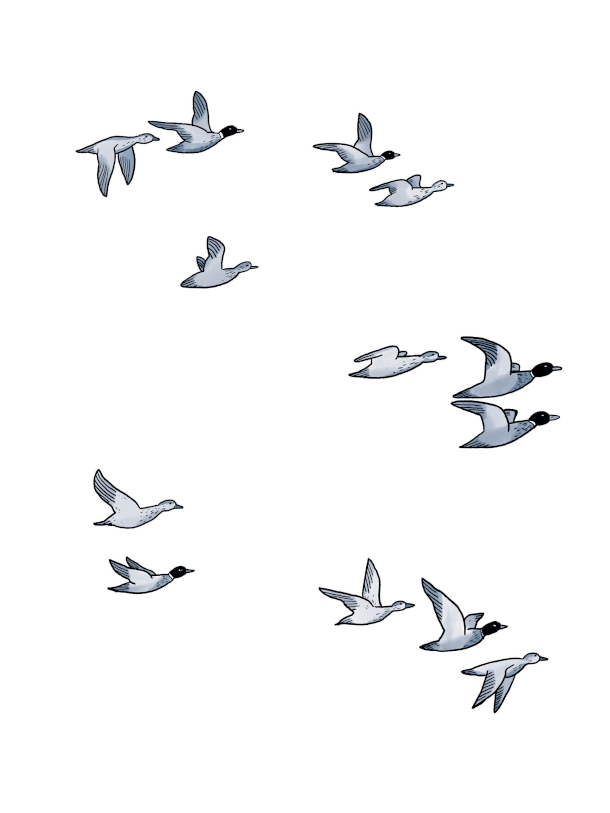

Ducks in flight. In 2008, around 1,600 ducks died after landing on a Syncrude tailings pond in Alberta. (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

BEATON: Sure. The book is called Ducks. And there are a number of different things that you can take from that title. The main thing is that there was an incident in 2008, when I worked in the oil sands, when hundreds of ducks flew into a tailings pond at Syncrude, which is one of the sites that I worked at, and they died. And this became international news. And it was one of the first times where people really took a hard look at what was going on in the oil sands and decided that they didn't like it. When we were working there it seemed to be farcical because it was not as though those were the first animals that you saw that were endangered or dead because of the oil sands operations. And when you're reading the book, it's not the first animals that you encounter who have been impacted by these things. Around that same time, local Indigenous people were catching fish, and saying that they were finding cancerous lesions on them. And people were scrambling to find ways to discount that, to disprove it, to say, "No, I don't think so. I don't think this is what you think it is." And people didn't seem to care about the fish in the same way that they did about the ducks. Because it was easy to see that the ducks were all dead. But it was harder to admit that an entire watershed was poisoned. And these Indigenous communities were also reporting themselves to have high rates of cancer, rare cancers, things like bile duct cancer in their communities, in Fort Chipewyan and Fort Mackay, much higher incidences of those in their communities than you find in other places. And they're saying amongst themselves and to other people, you know, it's clearly linked to the oil communities. And people are bending over backwards to say "No, probably not." [LAUGHS] When it, when clearly the link is there. And how would you feel if people around you were contracting these rare cancers, and the government was trying to deny it, and the corporations were not claiming responsibility, and then they went out and made a gigantic fuss about these ducks? And everybody cared so much about the ducks? You know, you would, you'd be like, disgusted.

DOERING: Why did you decide to go work in the oil sands?

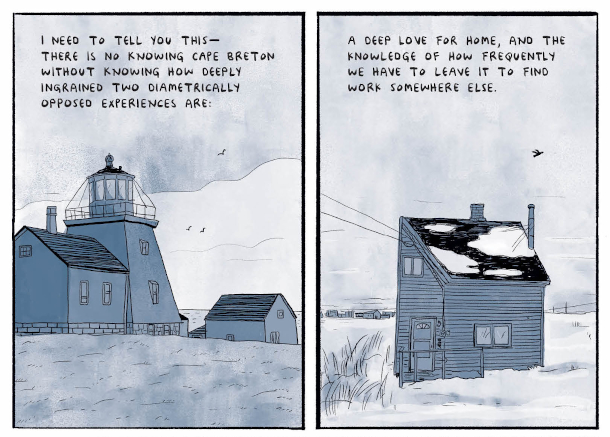

With $40,000 in student loans and no job prospects in her home of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Kate Beaton traveled West to work in the Alberta tar sands. (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

BEATON: At that time, in 2005, that was the place where everybody was going to work. I had graduated from university, and I had this debt. It was only $40,000. But the truth is that I maxed out both the federal and provincial loans to get it. And it was more money than I could possibly fathom owing to anybody. And if I paid back only the minimum, I would end up paying it back so many times over in interest by the time I ended up paying it back. In Cape Breton, we had a pulp mill, we had Sydney steel, we had coal mining; all three of those were shut down by the end of the '90s. Those were major employers. And when you'd go to the guidance counselors in school, and you were like, "What do I do?" And they were like "Leave. There's nothing here." It felt like you had no options.

DOERING: There is this trauma of environmental health. And you describe some of the health issues that you had working at camp, and some of the perceived health risks. Can you tell our listeners about those and whether any of those have persisted?

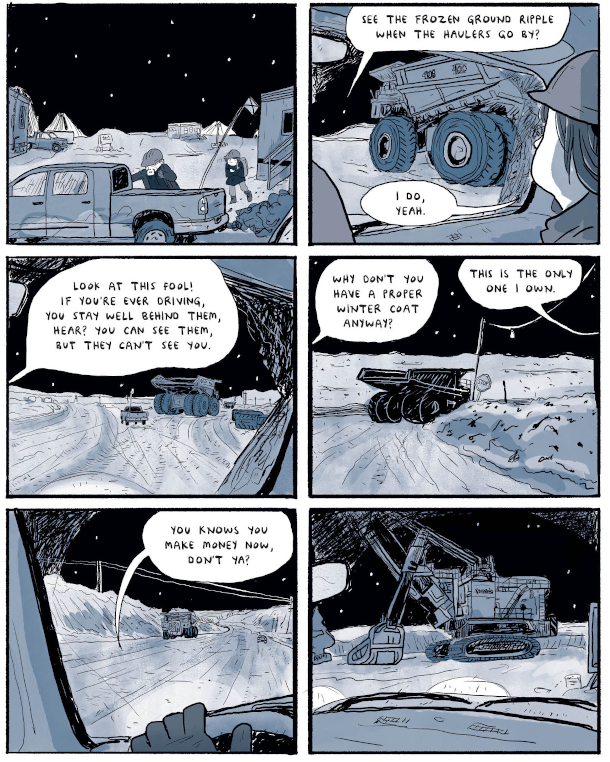

Traveling to the Syncrude oil sands mine (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

BEATON: Oh, yeah, there were lots. I mean, I think the first thing I drew in the book was when you would come home and you, I would always, like, cough up this weird gobs of things. I didn't know what they were; you'd just cough up this phlegm. And you'd be like, "Well, that was whatever I was breathing in all day. Don't know what that is." And I would get these rashes, especially on my back. They were from, like, what I assume is whatever was in the air rubbing between your skin and your clothes. Because we would come to work in the morning, when I worked in the office, like you'd be gone just like overnight, or maybe a couple of days. And you'd have to, like you could take your finger and wipe the film of dirt off the computer screen. So you knew that there was just stuff flying around in the air. Like that doesn't happen in your house. But it's flying around enough in the air there that it's settling on your desk in a short amount of time. So, you must be breathing it in all day. And everywhere you went, the signs were like, "Non potable," like, the water is non potable. So you had to drink from jugs of water that they had. It was like, it was an active mine.

Kate Beaton’s comic self-portrait. (Image by permission: © Kate Beaton)

The dangers were everywhere. We would have meetings every morning, safety meetings about how to not slip and fall and how that kind of thing so that if we hurt ourselves on site, the company couldn't get sued. But we never talked about things that would happen in the long run. Because anecdotally, you hear about people getting cancer who worked for a long time at Syncrude or Suncor, but no one's going to trace that back to the company. And no one is going to do a study on people who were working in the camps. If they worked there for a decade, and they got cancer two years later, no one's going to link that back. And no one's going to do that study, because who's going to fund it? The Alberta government? Yeah, right. My sister got cancer. Several years after working on site, and she, she worked there for longer than I did, several years longer than I did. And she had cervical cancer. And that's not related to breathing in things, and. But it spread so fast through her body that you will always wonder.

DOERING: I'm so sorry about your sister -- Becky, I think?

BEATON: That's right.

DOERING: Yeah, she's a pretty important character in the book.

BEATON: Yeah. And we joked about getting cancer in the book. I wrote that line in there before we even knew she had it.

DOERING: During your two years working in the oil sands, you experienced sexual harassment and assault, which you depict in your book Ducks with the lead up, and then just jet black pages completely filled with ink. How did the experience affect you emotionally?

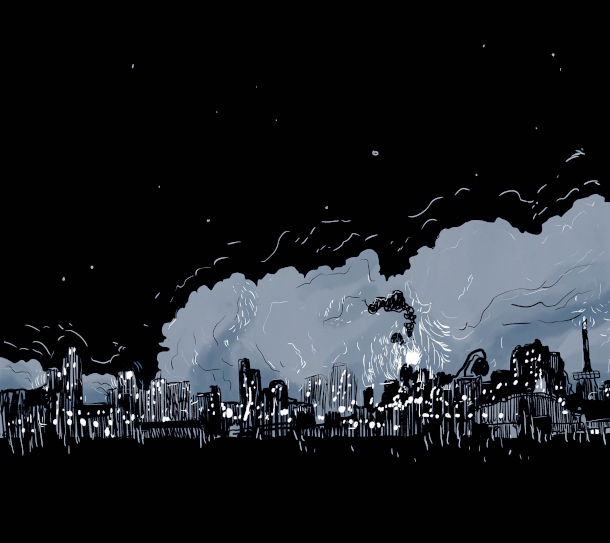

The Syncrude oil sands mining complex at night. (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

BEATON: Well, there was the harassment on the job, in the heavily masculine environment. It was nothing like I had ever experienced before, and I was completely unprepared for it. And even if you think that, it's going to be bad, it's nothing like what it is in person, the relentlessness of it. Because you don't just work there, you live there. You live in the work camp; you get up in the morning, and you go to work, and then you go home at night, and you sleep next to everybody. You shower with them in the morning, you eat your meals next to them, and there is no escape from it. There are people who don't know that they make you feel unsafe. There are people who don't care that they're bothering you. There are people who think that they have a connection with you because they are lonely. And they don't know that you are desperate to get away from them. It's not like regular society at all. And it becomes so much your new reality that you become inured to how much danger you're in, you stop pushing back. And when I did complain to my boss, when I was in a situation that was unsafe, he told me that he had no room for people looking for special treatment, and I felt ashamed. It was a signal to never complain again. And you don't want to be anything but a good worker, you want to be seen as a good worker, you are there to do the same job as everyone else. And you want them to respect you. When an episode of, of actual sexual violence happens, in retrospect, it wasn't surprising, although I never saw it coming. And in fact, it happened twice in a row very quickly. I had stopped seeing the danger around me because it was everywhere. And I was like a shell of myself. So of course, this was traumatic. And I carry that with me to this day. But I do not think that the men who raped me consider their acts to be rape. We came out of that place with different memories of what happened.

DOERING: What kind of support did you feel that you had, or didn't have, you know, from official channels and also in your personal life when this happened?

A panel from Ducks expressing the dangers of the heavy hauler trucks in the Athabasca oil sands. (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

BEATON: [LAUGHS] There was no support from official channels. It was a place that prided itself on being a happy place for women to work. If you went to the website, you saw smiling women in hard hats and smiling people of color. It paid a lot of lip service to the idea that there was a zero-tolerance policy for things like harassment, which was just complete nonsense. But I did have support from my friends who were there. My sister was there, and my friend from university who joined me. And there were other female workers there, who you knew were going through the same things as you, and you could talk to them. I was lucky to have people who were close to me that I could talk to eventually. But it's not like it happens immediately, when something traumatic happens to you. You don't start processing it immediately. And that happens, I show it in the book -- it takes a while to talk about it and to understand my own feelings about it.

DOERING: Can you help me understand the way that you intersperse this image of bare feet on a shoreline throughout the book repeatedly? I think it returns again and again amid traumatic events. And it feels like it's kind of an escape or a balm for you, but I wanted to hear you talk about it yourself.

BEATON: Sure. That's the West Mabou beach in Nova Scotia. That's the beach in my home village. It's a very beautiful place. It's always peaceful. It's funny, growing up here, you can be like, "I need to get out of here. This place sucks!" In almost any kind of like beautiful, like bucolic rural space, the kids can be like, "I wish I went to, I wish I could go to a mall." Then you grow up and you leave and you come back and you're like, it's beautiful here. I see why tourists like to come here. [LAUGHS] You like took something for granted your whole life. And then you miss it so much. So these reoccurring images in the book of the feet in the water on the shoreline. It's kind of like, knowing where you're from, and where you're safe, and where you belong.

Steam-assisted gravity drainage is an “in-situ” oil recovery method in the oil sands. It requires heating steam, usually by burning natural gas, to force oil out from underground. (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

DOERING: You managed to portray glimpses of beauty and wildness amid this grim landscape of the oil sands. Can you share what the Northern Lights and the pictures by your coworker represented for you there?

BEATON: The Northern Lights were beautiful. I had never seen them before. It was a night that was freezing. And they, they put me in a, in a shutdown shift, which is one where people are working overtime to fix this broken machine thing. And so I was alone in a tool crib. And it only had this tiny heater to heat it and it was minus 50 Celsius. And I don't know what that is Fahrenheit, but it's very cold. And a bunch of the workers had left a bunch of dirty tools outside and the bitumen had frozen on and I had to use degreaser to clean them all, but it was, they were all frozen. So I had to clean them really hard to get it off because it was so cold, but they were all metal as well, so they were all frozen solid. And my hands were just like popsicles. And all I had was that tiny space heater. So, I was laying on the floor next to it a lot of night as well. And I remember crying on the floor too, because I-- I never felt so alone. And then I walked outside to get another bucket of those tools. And I, I looked up, and the Northern Lights were above. And they were beautiful. And I took my helmet off. And I just I stood there staring at them for as long as the cold let me, because it was so beautiful. Before I left, there was a man, I called him Norman in the book. His name was Conrad Tabak. He had taken up photography as a hobby. He was like, "Everybody's got to have something to do here that makes them happy." He was a lovely man, an older, older man. And he went out when the Northern Lights were out, and he would go and take photos. And he was making blown up copies for people. He gave me one before I left, I still have it. It's downstairs. He was always looking for these beautiful things to take pictures of. But he died of cancer this year, just before the book came out. And I was so sad to hear that, because he was such a nice person. There were lots of nice people there. There were lots of nice people who looked for the beauty in things. It wasn't all terrible people. There were nice ones.

Cartoonist Kate Beaton (Photo: Morgan Murray)

DOERING: You now live back in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. And I'm wondering what are things like there now, economically, socially, what does it feel like to be back?

BEATON: Well, it's different than when I left. It's not as bleak. Coal mining is gone; well, actually, they keep trying to bring coal mining back, but it's gone. Steel is gone. The pulp mill is back. But it's not the same as it was. The Internet has changed a lot, you know. We didn't have the internet when I left, really. But now, you know, people can work from home and they can start new businesses here. It really changes how a rural economy can operate when you have online options. And so someone like me can, I can work from here, whereas before I would have to live in a city or something like that, but I can, I can live here. There are more and more young people moving back, and people are hopeful about it. It's nice. And I'm glad to be part of that.

DOERING: Kate Beaton is the cartoonist author of "Ducks: Two years in the Oil Sands" and creator of the comic strip "Hark! A Vagrant." Thank you so much, Kate.

BEATON: Thank you, thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Find the book Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands here (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Kate Beaton’s Hark! A Vagrant comic archive.

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Over My Head” on Blessed Quietness: A Collection of Hymns, Spirituals, and Carols, anonymous 19th century African-American spiritual, Atlantic Records]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show.

Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth