October 4, 2002

Air Date: October 4, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Colorado Senate Race

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood talks with Susan Greene of the Denver Post about the tight Senate race in Colorado and how environmental issues might affect the outcome. (06:40)

G-E Labelling

/ Henry SessionsView the page for this story

Voters in Oregon will decide next month whether food that is genetically modified should carry a label. Henry Sessions reports the food industry is waging a concerted campaign against the measure in the first real U.S. battle over GM labeling. (04:30)

Health Note/Hepatitis B Research

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on research that suggests a combination of western and Chinese medicines could benefit patients with hepatitis B. (01:15)

Almanac/Behold the Perm

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about the permanent wave. Ninety-six years ago, the world's first perm was an all-day affair, hot and smelly, but the end product was lasting curls. (01:30)

Park Neglect

/ Sandy HausmanView the page for this story

Many of the famous features that draw people to America's national parks are in a sorry state of disrepair. They're remote--expensive and even dangerous to fix. Sandy Hausman reports from the sweeping heights of Glacier National Park in Montana. (07:00)

Ode to Dirt

/ Rebecca McClanahanView the page for this story

Rebecca McClanahan reads "Something Calling My Name", her poem about a woman from Alabama who gave up her passion for tasting a bit of clay now and again to please her husband. (03:00)

Letters

View the page for this story

This week, we dip into the Living on Earth mailbag to hear what listeners have to say. (02:20)

Zen Garden

View the page for this story

Scientists in Kyoto have discovered what may be behind the extraordinarily calming effects of Japanese Zen gardens. Host Steve Curwood discusses these findings with researcher Gert Van Tonder. (03:00)

Animal Note/Insect Tune-Out

/ Maggie VilligerView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Maggie Villiger reports on how crickets are able to make an earsplitting racket without deafening themselves. (01:20)

4-H Youth

/ Bill GeorgeView the page for this story

The drought has had a devastating effect on Colorado’s agricultural community. But that didn’t stop the town of Rocky Ford from holding its annual Arkansas Valley Fair. Producer Bill George follows the Schweizer family as they enter their livestock in this year’s 4-H competition. (05:15)

Family Ties

/ Robin WhiteView the page for this story

We hear a lot about the loss of family farms, but less about those that are making it. Some of their struggles are not financial, but familial. Robin White provides a view from inside. (09:00)

EarthEar

View the page for this story

A symphony of nocturnal creatures at a mountainside in Papua New Guinea. Steven Feld Rainforest Soundwalks: Ambiences of Bosavi, Papua New Guinea ()

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodREPORTERS: Henry Sessions, Sandy Hausman, Bill George, Robin WhiteGUESTS: Susan Greene, Gert Van TonderNOTES: Diane Toomey, Maggie VilligerCOMMENTARY: Rebecca McClanahan

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR News, it’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

As the election season heats up, food and biotechnology companies are spending millions of dollars to try to defeat a ballot initiative in Oregon. The first-in-the-nation measure would require labels for genetically engineered foods. The federal government says biotech food is safe and the companies say labeling would hurt business. But supporters of the measure say consumers should have a right to choose

HARRIS: I have a lot of friends who are vegetarians. They want to know that they are getting lettuce and not lettuce with rat DNA in it, or broccoli with rat DNA, or tomatoes with flounder DNA.

CURWOOD: Also, the downside of up close and personal livestock farming.

ANDY: I’m going to miss my steer because I worked with him all summer long. And you just get attached to him and it’s hard to let him go. I’m going to cry.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWS]

Colorado Senate Race

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. With the balance of power between Democrats and Republicans in the Senate hanging on just one seat, every Senate race this November counts. And in Colorado, the contest between Republican incumbent Wayne Allard and Democratic challenger Tom Strickland is particularly strident. Polls have the two candidates in a virtual dead heat, and the environment may be the key to how voters decide.

Susan Greene covers politics for the Denver Post. Susan, why has the environment emerged as an issue in this election?

GREENE: Well, the environment is always pretty big in Colorado. We’ve got a huge segment of the population that moved here for the mountains, for the national parks, the open space, and hundreds of thousands of Coloradans who make their living off the state’s natural resources by ranching, mining, farming, skiing, rafting, etc.

In this race, I think that, by all accounts, it may come down to the state’s Independents who make up a third of the registered voters in Colorado, and new residents, who are said to be, largely, moderate Republicans who likely moved here for environmental reasons and may, sort of, embrace environmental causes.

CURWOOD: Republican Wayne Allard is campaigning by claiming to have a strong environmental record. What do people say about his environmental record?

GREENE: First of all, what he says about his environmental record is that it’s great, and that he’s the most green senator ever to represent Colorado. He makes a lot out of his work passing legislation to designate Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant near Denver as a wildlife refuge. It’s been decommissioned for years. And he makes a lot out of his work helping to designate the great Sand Dunes National Park and the Spanish Peaks Wilderness Area, which are both in Southern Colorado.

He’s also done work on helping to clean up a place called Shattuck. It’s a hazardous waste dump in Denver. So, all of those things have won support among some environmentalists, although they point out some downsides, as well. On Rocky Flats, some say the wildlife designation is a ploy by the government to avoid totally cleaning up the plutonium and the uranium there. On the Sand Dunes, many people note that it won’t officially become a national park until it acquires more land from a program which Allard has not supported.

On Shattuck, I think that’s one of his more solid claims on the environment. And he was really on Shattuck, many say, far before any of our local Democratic congresspeople were actually on the issue.

CURWOOD: Looking at his broad voting record, where does Senator Allard stand on the environment?

GREENE: First of all, Allard is chairman of the Senate Renewable Energy Caucus. And Colorado is home to the National Renewable Energy Lab in Golden. And while Allard recently voted to secure, I think, a 15 percent budget increase for the lab, he’s voted against things like improving fuel economy standards for cars and trucks, and helped block a requirement that 20 percent of utilities energy comes from renewable sources. He also opposed a plan to triple the content of ethanol in fuel and that was very controversial in Colorado, not only among environmentalists, but also the farming community because ethanol comes from corn and that’s one of our biggest crops.

CURWOOD: I know Senator Allard has gotten into a bit of a scuffle this fall with the environmental advocacy group, the Sierra Club. What’s going on?

GREENE: Well, in touting himself as the most environmental senator in Colorado’s history, Allard has made a big deal about having received in the mail a membership card from the Sierra Club. And he’s carried it around with him and said if his record’s so bad, why would they want him as a member. This was a solicitation that went to millions of Americans nationwide, and you’re supposed to send in your $25 dollars for an actual membership.

Carl Pope, the Executive Director of the Sierra Club was in town recently and whipped out a membership card of his own. It was a platinum membership with the Republican National Committee, congratulated him for upholding the party’s ideals. Pope’s a Democrat, and said he’s no more an exemplary supporter of Republican values than Allard is an environmentalist.

CURWOOD: So, environmental groups are endorsing the Democratic challenger Tom Strickland in Colorado, but he doesn’t have an extensive public record on the environment. What was he able to do as United States Attorney when he was in office?

GREENE: Well, he was the United States Attorney for the last two years of the Clinton Administration and he prosecuted a few cases against polluters. But, really, his focus as U.S. Attorney was mostly on guns, not on environment. What he did before that when he was working as a private attorney, he was heavily involved in a 1992 ballot initiative to create something called Great Outdoors Colorado. It’s an agency that takes lottery money in the state and buys parks and open space. One thing that sticks in the craw of environmentalists is his record as a private lawyer and lobbyist. He represented a company that’s had to build a medical waste incinerator in one of the poorest neighborhoods in Denver, even though neighbors objected. And he also represented Louisiana Pacific which was fined for environmental violations at a lumber mill in western Colorado.

CURWOOD: So, Susan, what do you think are the biggest environmental topics that will be at issue as this campaign heads into the final weeks?

GREENE: One huge one is fire. As you know, we had a horrible fire season in Colorado this year. Both candidates support plans to thin forest and reduce the kindling in the national forests, but they disagree on how to do it. Allard supports a plan that would cut down far more trees and far more acreage than Strickland supports.

Also related to the fire season is the drought. This was the driest summer in more than 150 years in Colorado. Huge reservoirs were nearly depleted as early as July. Crops suffered long throughout the state went brown. And all this called attention to a lack of a statewide water policy in Colorado, which is not something that a senator has authority over, but both have called for a statewide water policy even though Strickland has done so much more loudly.

CURWOOD: Why is this race so close, Susan? I mean, typically an incumbent has a lot of advantages going into an election. Why are things so tight? And how much does the environment have to do with it?

GREENE: Some people say if the Democrats have any challenge in this election, it’s to appear strong on the economy which people are obviously concerned about. And if Republicans have a challenge, it’s to appear environmental. And, basically, you’ve seen the Sierra Club, you’ve seen the League of Conservation Voters, the Democratic Party, and Strickland’s campaign blasting Allard on his environmental record, and, to some degree, that may have been successful.

CURWOOD: Susan Greene is a staff writer with the Denver Post. Thanks for taking this time with us today, Susan.

GREENE: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Tom Strickland’s website

- Senator Wayne Allard’s website

- Rocky Mountain News.com Candidate Profiles

- DenverPost.com Profile of the candidates

G-E Labelling

CURWOOD: Oregon could become the first state in the United States to require labels on genetically engineered food. Ballot Measure 27 will put the matter to voters in November. The campaign has been intense, with biotechnology and food companies spending millions of dollars on advertising. Henry Sessions has our report.

SESSIONS: Donna Harris is a busy mom. At a Portland café on a brief break from the campaign, she says she got the idea for Measure 27 when she had her second child two years ago. She wanted to avoid foods with genetically engineered materials.

[SOUND OF BUSY CAFÉ]

HARRIS: We called formula companies. We called cereal companies. Nobody could give us an answer. They gave us a scripted message that was, may or may not contain genetically engineered food. If it does, it’s an insignificant amount, and it falls under FDA guidelines.

SESSIONS: Harris says Measure 27 is designed to address that lack of information. It would require growers, processors and distributors to label not only genetically engineered potatoes or fish, but any food contained GE ingredients, such as corn syrup or cake mix.

HARRIS: The one thing that was really important to me was, for example, if a tomato contained flounder DNA, that that be on there. And I think that’s important. I have a lot of friends who are vegetarians. They want to know that they are getting lettuce, and not lettuce with rat DNA in it, or broccoli with rat DNA, or tomatoes with flounder DNA.

SESSIONS: GE food labeling isn’t a new idea. The European Union requires it, as does Japan and several other countries. And despite a starving population, the southern African nation of Zambia is refusing to accept shipments of genetically modified corn. But in Oregon, the idea of labeling GE foods is leaving a bad taste in the mouths of some food processors, farmers and others.

MCCORMICK: The way it’s written, it goes well beyond what seems like any kind of a reasonable proposal. It means that virtually all the foods that we see in stores is going to have labels on it.

SESSIONS: Pat McCormick is a Portland lobbyist representing a food industry group calling itself the Coalition Against the Costly Food Labeling Initiative. They’ve recently gotten an infusion of money from outside the state.

MCCORMICK: The Food and Drug Administration has made it absolutely clear that these foods are no different and just as safe as their conventionally bred counterparts, and there’s no reason to separately label them. In fact, putting labels on them would be misinterpreted by consumers as a warning when there is no reason in the Food and Drug Administration’s mind to provide any warning since they believe these foods to be safe.

SESSIONS: McCormack points out that new national organic standards, which take effect later this month, already ban GE ingredients. So, consumers can avoid GE foods by buying organic. Sitting on the sidelines of this campaign are Oregon’s big natural foods retailers. Wild Oats Markets, with more than 100 stores in two dozen states, owns 10 stores in Oregon. On bulletin boards and in publications, Wild Oats has been at the forefront in informing customers in the debate over GE foods.

[SOUND OF CRINKLING PASTA PACKAGE]

SESSIONS: Mark Cockroft, regional marketing manager, pulls a bag of Wild Oats pasta off the shelf and points out that for their house brand, Wild Oats has switched to suppliers who don’t use genetically engineered ingredients. But Cockroft says Oregon’s labeling initiative poses a problem for a national company like his.

COCKROFT: It’s a controversial issue, and there’s not a lot of concrete scientific evidence out there. And really, in the end, our position comes down to the right of the customer to make an informed choice. However, on this matter, we really support a national label law, not a state’s label law.

SESSIONS: No polling numbers have yet been released on the measure, but independent political analyst Jim Moore says the initiative might well strike a chord with Oregon’s notoriously independent voters.

MOORE: If we see the big food companies, if we see, for instance, ads by ConAgra, or Archer Daniels Midland, or things like that coming in, there’s a real chance Oregonians can say, "You know, we aren’t quite sure about this GMO thing, but we’re not going to have those big people from Nebraska or Colorado telling us what to do."

SESSIONS: If Measure 27 passes, it wouldn’t be the first time Oregon has gone its own way. Among many other firsts, voters here passed the nation’s first bottle deposit and land use planning laws in the 1970s.

For Living on Earth, I’m Henry Sessions in Portland, Oregon.

Health Note/Hepatitis B Research

CURWOOD: Coming up, the fiscal crunch faced by national parks. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey.

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: Three hundred fifty million people worldwide are chronically infected with hepatitis B, a virus that can lead to liver damage and even cancer. A full three-quarters of those live in Asia. And many of them are treated with Chinese herbal medicine. Studies that gauge the effectiveness of this treatment for hepatitis rarely get published in English-language journals. So scientists at the University of California-Berkeley analyzed research that appeared in Chinese language journals. They reviewed more than two dozen studies in which one group of patients used herbal medicine alone or in combination with interferon, a standard hepatitis treatment.

That group was compared to patients who just received interferon. All the studies evaluated patients after three months of treatment by measuring their level of viral activity. Researchers found the most effective treatment appeared to be a combination of Western and herbal medicine. In three standard blood tests, the patients who received both those treatments were up to twice as likely to have reached an undetectable level of virus compared to patients who received interferon alone.

While the Berkeley researchers found these results promising, they did have some major criticisms of the Asian scientists’ methodology. So they say they plan to help train a group of Chinese clinicians on how to conduct more rigorous experiments in the future.

That’s this week’s Health Note. I’m Diane Toomey.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living On Earth.

[MUSIC: Miles Davis, "Right Off," A TRIBUTE TO JACK JOHNSON (Columbia, 1992)]

Related link:

UC/Berkley Media Release on Hepatitis B

Almanac/Behold the Perm

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Beck, "Devil’s Haircut" Remix, ODELAY (DGC, 1996)]

CURWOOD: Ninety-six years ago this week, Karl Ludwig Nessler placed an ad in London’s Hairdressers’ Journal. He invited leading hairdressers to "inspect and judge a lady’s hair waved permanently by his newly invented and greatly improved process that would withstand water, shampoo, and all atmospheric influences."

It was the world’s first perm. And Mr. Nessler accomplished the effect by winding hair tightly around brass rods that weighed as much as two pounds apiece, and connecting the curlers to an electric power source. The old shebang looked like a huge milking machine hung from the ceiling. And it worked by using heat and a highly alkaline solution to break the chemical bonds that give the hair its shape. Then, an acidic solution reformed the hairs bonds so it stayed curly permanently.

The perm’s popularity peaked in the 1960s. But last year, Americans still spent almost nine billion dollars on salon curls and hair straightening treatments. Studies say the chemicals used in today’s perms are relatively safe. The most typical adverse health effects are skin irritation and allergies. The search is on for a chemical-free perm recipe. But, so far, natural ingredients haven’t been able to hold their own against Mr. Nessler’s formula. And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC: Beck, "Devil’s Haircut" Remix, ODELAY (DGC, 1996)]

Park Neglect

CURWOOD: While he was running for president, George W. Bush pledged nearly five billion dollars to repair the nation’s parks. And this year, Congress is debating a big increase for long needed maintenance. To assess the need, we sent reporter Sandy Hausman to Glacier National Park in Montana, a million acres of snowcapped mountains, deep green valleys, and clear, cold streams. You might call it calendar country. But, observers say it’s also a poster child for the Park Service--proof of serious, even dangerous, neglect.

[SOUND OF VISITOR ENTERING GLACIER]

RANGER: How are you?

MAN: Hello, I’m fine.

RANGER: Need any current information?

MAN: Yes, that’d be great, if we could get a brochure.

RANGER: Here’s a newspaper. Our visitor’s center is in Apgar, two miles ahead.

MAN: Okay, thank you very much.

RANGER: Sure, thank you.

HAUSMAN: Every year, nearly one and a half million Americans drive through Glacier National Park on a remarkable 50 mile road built in the 1920s and ’30s. The Going-to-the-Sun Highway is considered an engineering marvel. It clings to the side of the mountain, rising from 3000 to 6600 feet above sea level to cross the Continental Divide.

Going-to-the-Sun Road, Glacier National Park (Photo: NPS)

Building this road was such dangerous and delicate work; it probably wouldn’t be done today. But, 21st century visitors are glad it’s here. Greg Myers stopped to admire the view after driving in from Madison, Wisconsin on his Harley.

MYERS: Definitely worth the 2,000 mile trip just to go up and down that hill once, put it that way. This is the second time we’ve taken it. And, it’s gets better every time. You got to remember to watch where you’re going, as well as watch the mountains. Otherwise, you end up in trouble.

HAUSMAN: Right off the edge.

MYERS: Right off the edge.

HAUSMAN: Visitors here sometimes see big horn sheep, mountain goats and grizzlies. Park literature warns tourists of the potential risk posed by bears. But there is no warning about what may be a more serious threat to public safety.

[SOUND OF SPLASHING WATERFALL]

HAUSMAN: Water is everywhere, eroding the ground under this road and setting rocks free above it. Several years ago, a Japanese tourist was killed when a boulder fell on his car. And Fred Babb, chief of project management at Glacier, says the risk is constant.

BABB: Everyday the Park Service has one gentleman that goes the entire length of the road just sweeping stone off the road. If he didn’t do that, in a matter of a week, the sections of the road would be completely covered by stone, and not passable.

HAUSMAN: Snow is also a problem during Montana’s long, cold winters. Steve Thompson, local program manager for the National Parks Conservation Association, leans over a cliff and stares at a pile of rocks below.

THOMPSON: Looks like there was probably an avalanche that came through there not too long ago, and just took that retaining wall right over the edge.

HAUSMAN: So, in the summer and fall, crews are busy restoring the road.

[SOUND OF CONSTRUCTION GENERATOR]

HAUSMAN: About a mile below the highway summit, two men are standing on a platform hanging over the edge of a cliff, suspended from a crane. Construction worker Bruce Wann says they are replacing the mortar in the guard wall. And this is the only way to reach it.

WANN: And then we got guys on the ropes to keep them from swinging around if the wind comes up, which it does up here. And the other hazards we have to deal with are lightning. The crane is a giant lightning rod. And if we get a lightning strike in the area, then we have to shut down.

HAUSMAN: All total, six men will need about a month to fix 150 feet of wall. One stretch of wall in one national park, one reason why park repairs can be costly.

[SOUND OF LOBBY IN MANY GLACIER LODGE]

HAUSMAN: Near the end of the Going-to-the-Sun Road, on the east side of Glacier, stands a historic lodge named for the surrounding ice and snow. The Many Glacier Hotel, with its large friendly lobby, is one of the three chalets built by the Great Northern Railway to attract park visitors.

In 1915, when the hotel opened, it was a bastion of elegance for the adventurous traveler willing to make the trek by train and horseback. Today, the lodge draws as many as 700 guests a night from around the world. But manager Don West says some are disappointed by conditions here.

WEST: Last year, at this time, if you were to walk down the hallway, you would get vertigo because it was so much slanted in--it was falling into this lake.

HAUSMAN: Money for repairs finally arrived after members of Congress held a hearing in the lodge and saw the slanted hallway’s peeling paint and frayed carpets. But Congress has not yet funded road repair. That’s a tougher sell, says Steve Thompson.

THOMPSON: You know, when people come to visit the park, they’re focused in on the beauty of the park. And they want to see a bear. And, they’re not thinking about, you know, sort of what makes it all run. The backlog of basic maintenance projects, such as the Going-to-the-Sun Road is about $5 billion dollars.

HAUSMAN: That’s why his group has joined with local Chambers of Commerce, national environmental groups, service organizations, even the Girl Scouts, to form a parks advocacy group--Americans for National Parks.

But some people don’t share their view that Congress should pay to keep the parks in good repair. Instead, economist Randal O’Toole thinks the Park Service should raise admission fees, charging per person, per day. Right now, visitors pay just $10 per car per week at Glacier.

O’TOOLE: How much do you pay to go see a two-hour movie? How much do you pay to rent a video? Paying three to five dollars per person per day to visit a national park is still pretty cheap.

HAUSMAN: He also thinks the Park Service should be more selective about acquiring new buildings and property. For example, when the giant Presidio Military Base in San Francisco was given to the Park Service, it came with about 500 historic buildings and manicured grounds that are extremely expensive to maintain.

O’TOOLE: It’s nice to have that 1,480 acres. If you live in San Francisco, it’s essentially a city park, enhances the property values of people in San Francisco. But it doesn’t really benefit people anywhere else in the country.

HAUSMAN: O’Toole calls this "park barrel" and refers to the National Pork Service when he suggests that no tax dollars be used to fund places like Glacier and the Presidio. As the debate continues, Congress is set to approve about $130 million dollars more than the Clinton administration did to reduce the maintenance backlog. That does not include major roadwork. Congress will look at that next year when it considers funding for the nation’s highways.

But with some Montana clout on the Senate Appropriations Committee, Glacier is hopeful that money to rebuild the Going-to-the-Sun Highway will come through in 2004.

For Living on Earth, I’m Sandy Hausman in Whitefish, Montana.

Ode to Dirt

CURWOOD: A research letter in a recent issue of the journal The Lancet corroborates the notion that children who grow up on farms have fewer allergies because they are exposed to a lot of microbes in the soil.

Country kids play in dirt, dig in dirt, and sometimes love to eat dirt. Not all of them outgrow the urge. And that brings us to a poem by Rebecca McClanahan. She writes about one southern woman who gave up eating dirt for her husband. It’s called "Something Calling My Name."

MCCLANAHAN: I tried to tell him. But he won’t hear.Earl, I say, it’s safe. It’s cleanif you dig below where man has been,deep to the first blackness.I tell him. But he won’t hear.Says my mouth used to taste like mud,made him want to spit.

I tried to tell him how fine it was.When I was big, with Earl, Junior and Shad,I laid on my back, my belly all swelledlike the high dirt hillssloping down to the bankabove the gravel road by Mama’s.And I’d dream it. Rich and black after rain.Like something calling my name.

I’d say, Earl, remember? That spring in Chicago,I thought I’d die, my mouth all tasteless,waiting for Wednesdays, shoeboxesfull of the smell of home.The postman, he’d scratch his head,but he kept on bringing. Bless Mama.She baked it right, the way I like.Vinegar-sprinkled. And salt.I’d carry it in the little red pouchor loose in my apron pocketand when the day got too long and dryand Earl home too late for loving,I’d have me a taste. It saved me, it did.

And when we finally made it back,the smell of Alabama soilpoured itself right through me.I sang again, and things were finetill the night he leaned back and said"No More," his man-smells, all richand mixed up with evening. Right there,laying by me, he made me choosebetween his kisses and my clay.

Now, afternoons when it gets too much,I reach for the stuff he gave me.Baking soda. Starch. I’ve tried it all.But I don’t hold with it.It crunches good, but it’s all bleached outand pasty. It just don’t take the place.

Earl, I say, I’ve given it up.And right then, I have.But sometimes, on summer nights like thiswhen the clouds hang heavyand I hear that first rumble and the earthpeels itself back and the crust darkensand the underneath soil bubbles updamp and flavored, it all comes backand I believe I’d do anythingto kneel at that bankabove the gravel road by Mama’sand dig in deep till my arms are smearedand scoop it wet to my mouth.

CURWOOD: Rebecca McClanahan is a writer who lives in New York City. Her latest collection of essays is called "The Riddle Song and Other Rememberings."

Related link:

Rebecca McClanahan’s website

Letters

[LETTERS THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Time for comments from you, our listeners. Our coverage of the World Summit on Sustainable Development included a story about South Africa’s proposed pebble bed nuclear generators. Reuven AnafShalom heard the program on WUNC from Chapel Hill, North Carolina. He says the issue of how the spent fuel would be dealt with was given short shrift in the story. "The biggest problem with nuclear energy," Mr. AnafShalom writes, "is the waste it produces, and how to dispose of it."

Jennie Oppenheimer heard the story on KQED in San Francisco, and emailed us to say that we should have included more voices of nuclear critics. "Of all the exciting sustainable clean technologies on the forefront of development," she wrote, "I was disappointed by your choice of what to highlight."

Our report on the military’s request to be exempted from some environmental protection laws drew this comment from WQCS listener Marty Bergoffen from Asheville, North Carolina. He writes, "The Department of Defense and the Armed Services have demonstrated very convincingly, over the past 30 years, that they can both comply with environmental laws, and still be the best and most ready military force. We would be well-served to remember the words of Dwight D. Eisenhower who cautioned, "The problem with defense is how far can you go without destroying from within that which you are trying to protect from without."

And Dan Hutzley, another North Carolina listener who hears us on WUNC in Chapel Hill, says our profile of mockingbird scientist Cheryl Logan prompted him to report that mockingbirds that frequent a patio at his office have a new song in their repertoire. Mr. Hutzley says he’s been outside when a mockingbird lets out a song that sounds like a cell phone ringing. "It’s interesting to see that people look around for the cell phone, only to see it coming from the trees."

You can make our phones ring anytime by calling our Listener Line at (800) 218-9988. That’s (800) 218-9988. You can also write us at letters@loe.org. Once again, letters@loe.org. And visit our web page at loe.org. That’s loe.org.

[LETTERS THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: You’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

Zen Garden

CURWOOD: Japanese zen gardens are landscaped with raked gravel and carefully placed rocks and moss. And although they look sparse and bare, these can have a strong calming effect, as I found out once when I visited the Ryoanji Zen Garden in Kyoto a few years ago.

Now, a team of scientists is saying that the rocks and moss there conceal an image of a tree that exists only our minds. Gert Van Tonder, a visual cognitive researcher at Kyoto University, explains what happened when his team started doing mathematical computations with the patterns in the garden.

VAN TONDER: I first thought I would just get a scattered pattern of lines going off into various directions. But it turns out that the medial access lines in the simulation form a converging pattern. And it converges onto the main viewing area of the veranda in the temple.

And this converging structure resembles a tree. We did a number of analyses on these branches. And, for example, we found that, if anybody would just randomly throw their rocks onto that piece of gravel, they wouldn’t nearly come close to finding such a nice converging tree structure.

CURWOOD: How would you explain this to our listeners? How do you explain the idea of seeing a tree in negative space?

VAN TONDER: Try to image to see a tree that’s invisible, except for its leaves. So, in a similar way, in the garden here, the rocks form the leaves of this invisible tree. And while you’re not necessarily aware of it, the branches and the trunk is right there in front of you.

CURWOOD: How much do you think the designers of this garden were aware, or knew about, the subconscious picture that they were creating?

VAN TONDER: Well, I think we would be a bit reluctant to say that they consciously thought of a tree structure, and then went ahead with the design. But they must have had a very highly developed or sophisticated intuition of their own subconscious perception so that they could adjust the rocks and, thereby, also this invisible tree until it felt just right.

CURWOOD: How important is it for the calming effect that a tree is the image that’s implied?

VAN TONDER: Well, I think I can only answer with a puzzle. The image of a tree in Buddhism is important in the story about the moment when the Buddha finds enlightenment. And he does so at the foot of a tree. So, that could be a possible clue for people who want to think about this.

CURWOOD: Thanks for speaking with us today.

VAN TONDER: It’s a pleasure.

CURWOOD: Gert van Tonder researches human visual cognition at Kyoto University. To see the results of his work at the Ryoanji Zen Garden, go to our website at loe.org. That’s loe.org.

[MUSIC: Rita Takashima, "Ito Akashi," PASSENGERS: ORIGINAL SOUNDTRACKS I (Island, 1995)]

Animal Note/Insect Tune-Out

CURWOOD: Just ahead, the pleasures and perils of the end-of-summer fair. First, this page from the Animal Notebook with Maggie Villiger.

[ANIMAL NOTE THEME MUSIC]

VILLIGER: Being loud is a good way to get your message heard. Just listen to the racket a tiny cricket can make.

[CRICKET CHIRPING]

VILLAGER: But if you listen to a sound at this level for too long, you run the risk of deafening yourself and missing important sounds in your environment.

Now, scientists have figured out how crickets stop their ears from being blown out. A particular part of the insect’s brain is responsible. When a cricket sings its rhythmic song, it’s thanks to an impulse sent out by the region of its brain called the central pattern generator.

This network of neurons sends out two copies of its message at the exact same time. One is sent to the cricket’s muscles, telling the wings to rub together and generate the noise. At the same time, another dampening signal goes to the part of the brain that processes auditory input.

So at the same moment, the muscles get the message to sing, the auditory system gets the message to shut down. In between its bursts of song, the cricket’s hearing returns to 100% so he can hear other sounds around him—hopefully, the approach of a romantic female. That’s this week’s Animal Note. I’m Maggie Villiger.

[ANIMAL NOTE THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Miles Davis, "Right Off," A TRIBUTE TO JACK JOHNSON (Columbia, 1992)

4-H Youth

CURWOOD: It’s Living On Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: If there is one rite of passage for farming kids as they head from the summer into the fall, it has to be the local fair. And this year, despite widespread drought that’s forced many farmers to sell of their herds, 4-H youth still spent months preparing their livestock for competition. Producer Bill George caught with the Schweizer family at this year’s Arkansas Valley Fair in Rocky Ford, Colorado to bring us this sound portrait.

[SOUND OF WATER IN BUCKET]

ARLENE: My name is Arlene Schweizer. I live here in Rocky Ford, Colorado. We live on a farm and ranch.

[METAL BUCKETS BEING SET DOWN]

ARLENE: It’s been a really tough year, very tough year. My husband and I never thought it would be as dry as it is.

[FEED BEING SCOOPED INTO BUCKETS]

ARLENE: At our county fair we see a lot of positive things going on. You see kids that are happy. You see kids that are excited to show their animals. And I think it will be important for us to see that, because it’s been pretty devastating. Farmers are not wanting to talk about how dry it is because that’s all we’ve heard for about the last five months, and you just get tired of hearing about it. So I think the fair will be exciting.

[SOUND OF SHEEP BEING BLOW DRIED AT FAIR]

CHRIS: My name is Chris, and this is my brother Andy, and he is older than me.

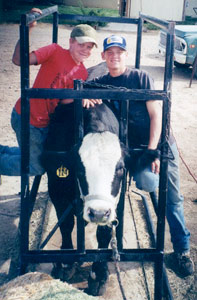

Chris (left) and Andy with one of their steers.

ANDY: Right now, in the barn it gets really loud because I have sheep and goats and steers that get really, really wild. And it gets kind of exciting because the steers get ready to run.

[SCALE CLANKING]

ANDY:I’m going to fall over and die if we raise over 1300.

JUDGE: 1428.

[MURMER OF PEOPLE IN THE BACKGROUND]

JUDGE 2: He ate his Wheaties!

ANDY: My black steer, he weighed 1428, and he started at 695. So he gained 700 and some pounds. And I got second rate of gain. What that means, what they do is they take all this stuff and they divide it, and they figure out how much they gain per day. And I think my steer gained, like, three something per day.

MICHELLE: My name is Michelle Schweizer, and I’m Andy and Chris’ sister. And I took the week off so I could help them at the fair and get things lined up for them. I showed steers down here for nine years, and I always loved the fair. It’s like the best part of my summer.

[ROOSTER CALLING AND CATTLE MOOING]

MICHELLE: It’s kind of nerve racking sometimes, but it’s still fun. It’s exciting to see your brothers do good.

[SOUND OF HOSE SPRAYING WATER]

CHRIS: We’re washing our steers to get them ready for our showmanship class. We have a drought this year, so you can’t wash your steer twice or three times. You can only wash ‘em once.

[SOUND OF BRUSHING]

CHRIS: I’m brushing my steer’s hair forward and we’re putting stuff on their hair to make it stay where it’s at.

[BRUSHING]

ANDY: It makes the hair stick out more so they look pretty.

[SPRAY PAINT CAN SHAKING]

ANDY: Now, my black steer, we’re going to paint some of his back legs black because he had some skin rubbed raw.

ANNOUNCER (over PA): Get ready. We’re getting ready to start here in about five to six minutes.

CHRIS: I’m really nervous.

MICHELLE: Brush!

[BRUSHING]

MICHELE:I had to remind him because they’re younger. They haven’t been doing it as long as I have and because they’re boys.

MAN: Good luck, Chris! Good luck, Andy!

CHRIS: Thanks!

ANNOUNCER: And that will take us down to the Junior Showmanship Contest here. Today is Andrew Schweizer, Chris Schweizer, Lacey Hood…

ARLENE (in a soft voice): Andy look at the judge, look at the judge.

ANNOUNCER: Let’s give all these young exhibitors a round of applause.

[APPLAUSE]

ANNOUNCER: Ladies and Gentleman, your grand champion junior showman this year goes to Jason Russell.

[APPLAUSE]

ANNOUNCER: Reserve Grand Champion Lacey Hood. Third was Andrew Schweizer, fourth Chris Schweizer, fifth, AJ ….

ARLENE: That’s all right. They’re here to learn. You know, win or lose, you’re here to learn. But you did a good job, Chris. I thought you did a very nice job.

ANDY: I’m going to miss my steer because I worked with him all summer long and you just get attached to him and it’s hard to let him go. I’m going to cry, probably.

AUCTIONEER: ... fine looking steer from Andrew Schweizer, Ladies and Gentleman. Five, 600, now seven….

[SOUND OF AUCTION AND PEOPLE BIDDING]

CURWOOD: Our sound portrait of the Schweizer Family at the annual Arkansas Valley Fair in Rocky Ford, Colorado, was produced by Bill George.

[SOUND OF AUCTION]

Family Ties

CURWOOD: We hear a lot about the demise of the family farm and it’s true that corporate agriculture owns most of America’s farm acreage. But if you look at the numbers of farms, 98 percent are still owned by families, according to the federal government. That means from Omak, Washington, to Swainsboro, Georgia, perhaps two million people wake up each morning and step outside to work with their sons, daughters, brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers, husbands and wives. We don’t often hear about their struggles, but for two years, Robin White has been following a farm family in California where the stress that comes from working with your relatives is pretty close to the surface.

[BIRD CALLING]

WHITE: When Ted Bucklin returned to the tight fields of vegetables and flowers at Oak Hill Farm in Sonoma County, he knew nothing about running the place. He was studying for a Master’s in Social Work when he got a call from his mother. His stepfather had died and the family was deciding how to run the farm. It sits under an oak-covered mountain in the heart of the wine country.

[MEXICAN MUSIC]

WHITE: Pretty soon, Ted found himself supervising 13 employees, some of whom had been on the farm half his life.

BUCKLIN: Well, this is Chuy Soto. Chuy’s been working at Oak Hill Farm for 20--how many years, Chuy? Twenty-two years.

[MEXICAN MUSIC]

WHITE: In the cutting room, three men are clipping the ends off flowers and tying them into bunches. Ted introduces them by full name, and then he points up.

BUCKLIN: If you look on the ceiling, you can see all the statice and corn and different flowers that we dry, going upstairs in the barn here you can see more flowers, and then there’s boxes of flowers. And so, year round we’re always sort of chasing after this rainbow of stuff that’s growing on the farm.

WHITE: If Ted Bucklin sounds a little overwhelmed, it’s probably because he’s had to learn the business quickly and he’s made some big mistakes. His mother hired him. He may not have been the best man for the job, but family farmers often put family ties first, especially when they’re short of cash. When Ted took over, the farm was losing $60,000 a year. He increased efficiency and fired some long time employees.

BUCKLIN: That’s the hardest thing I’ve had to do. We’re talking about families that lived on the farm for 15 to 20 years, children who were born on this farm who had to move. This was their home. Ugh.

WHITE: The firings led to protests among the employees. Out in the fields, Chuy Soto is in charge. Chuy says Ted tried to move too fast.

SOTO: At the beginning it was kind of hard. He wanted this place to change dramatically and he thought it would be changed [SNAPS] like that. I’d say, "Well, you know, it’s not going to happen just suddenly." Yes, we have hard times. I’ll tell you, once or twice I was ready to quit because we couldn’t communicate.

WHITE: Ted was risking one of his best employees. But it wasn’t just the workers who were upset. Some of the customers at the farm store were friends of the fired workers. In this small agricultural county, everyone is tied to everyone else and word got around. It was so unsettling that pretty soon Ted’s own job was on the block.

[PHONE DIALING]

BUCKLIN: Hello, Mother. Can I come in about 15 minutes?

Mom has been to the point of such dissatisfaction with me that she fired me and I just refused. I said, "No way, and you’re a fool for trying to." And since then, I’ve actually convinced her that she was wrong.

WHITE: Ann Teller is Ted’s mother.

TELLER: We have made a lot of mistakes. Some of the mistakes we’ve made together and some of them we’ve made in opposition to one another. And I’m sure it’s true in any family. You know, blood and money doesn’t always mix.

WHITE: If you spend any time in farming communities you start to hear stories of brothers who farm next to each other, but don’t speak anymore because of old arguments. And it’s not uncommon for older farmers to have trouble letting go of the reins. Steve Schwartz is with Farmlink, a Sacramento organization which helps farmers transfer property to the next generation.

SCHWARTZ: The best story I think was a dairy farmer. And he said, "You know, myy son, I’m really looking forward to him taking over the farm. He’s a great dairyman. He’s good with the cows. But he’s just not good with the books. So he’s really not ready to take over the farm yet." So it turns out this farmer is 87, and his son is 65.

WHITE: Schwartz says poor communication is all too familiar for families working together.

SCHWARTZ: We talk to a guy who literally had a 45 second conversation with his mother 15 years ago and she said, "I don’t think there’s room for you here." And he took that to mean, "I better go move off soon and take my family and rent somewhere and do my farming elsewhere." And that’s not exactly what she meant.

WHITE: Chuy Soto understands the differences between things said and things understood. The workers he manages at Oak Hill Farm are his own relatives, another family on this farm. He likes the confidence of hiring family, but sometimes he has to say hard things.

[SQUEAKING BRANCH OUTDOORS]

SOTO: If we take this outside of work, it can be tough. He’s my uncle, he’s my cousin, he’s my brother-in-law. And sometimes if I am hard on them, for whatever reason, I go out there and apologize--"this is work related and don’t take it personal."

WHITE: If disputes are allowed to rankle, it sometimes takes a long time to get over them.

[SOUNDS OF BARKING DOGS]

WHITE: One farming family with a lot of history is the Hansens of Selma, California. On a walk around his peach orchid, farmer and writer Victor Hansen points out an old white hay barn.

[FOOTSTEPS CRUNCHING GRAVEL]

HANSEN: Barns are kind of strange. I see them all over. There’s one over there. They have no shape that’s of any value.

WHITE: There are no draft horses needing these hay these days, and the barns are no longer much used, but people still hold onto them. It’s the same with family feuds. Back in his old farmhouse, Victor tells of grudges that went back four generations.

HANSEN: I was told that when my great, great grandmother died, this must have been about 1877, one of the brothers walked into this very house and hadn’t seen her for 30 years, and stripped all of the rugs out of the house and then demanded his land. I have no idea if that’s true, but my side of the family told me that and I was not to like that side of the family.

WHITE: A few years ago, Victor made his own brother angry by writing a book about their farm. His brother found the book too close to the bone and the men didn’t speak for two years. Only later the brothers began talking again. They still have things in common.

HANSEN: One hundred twenty years on a farm. There’s depressions, there’s war, there’s people who have been killed. There’s incidents like that, and they come and go.

[SOUNDS OF BOTTLING]

WHITE: Back at Oak Hill Farm, things have also come full circle. Ann Teller has, more or less, stepped down. And, one by one, Ted’s brother and his sisters have returned from living across the country. Together, they’ve launched a new venture. They’ve always grown grapes, but they used to sell them to Ravenswood who’d turn them into a famous zinfandel. Now, the Bucklins have decided to make their own wine

BUCKLIN: This is our first bottling and we sort of have it down. We’re having fun. I’m really enjoying this. Yesterday, we made a thousand boxes. It’s kind of fun being part of a family machine.

WHITE: Will Bucklin is the vintner. Kate and Arden and their friends are also here giving up their weekend to bottle the new wine.

ARDEN: I’m a sister. I’m the member of the family. There are four of us.

WHITE: They’re four of you. So, you’re the last…

ARDEN: Well, I’m actually the second, if you must know. Will is the last.

WHITE: And Ted is the oldest?

ARDEN: Ted is the oldest, yeah. It’s really obvious.

MAN: We do whatever Ted tells us to do.

ARDEN: That’s not true.

WHITE: The cap on the new wine bottle is inscribed with "B4", for the four Bucklin siblings. Kate Bucklin says, most families are not as close as they are.

KATE: We’ve really grown as a family. Whereas, I don’t think most families have that opportunity to really go through and, one-by-one, knock off the big problems.

Oak Hill Farm staff (Photo: Wendy Westerbeck)

WHITE: The farm ties the family together. And for all the hardships, the Bucklins and the Hansens say, they wouldn’t do anything else.

For Living on Earth, I’m Robin White in Sonoma.

[MUSIC: Miles Davis, "Yestersnow" A TRIBUTE TO JACK JOHNSON (Columbia, 1992)]

EarthEar

Related link:

Buy this CD online

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living on Earth. Next week, how a good thing went bad when the government moved in to cleanup pollution from a Montana silver mine.

MALE: God damn it, don’t misunderstand me, okay? The original EPA guys that came up here to do this cleanup are decent, honorable people. What you got now is a bunch of little Gestapo and I would not suggest that anybody not use any means available constitutionally, or otherwise, to oppose that.

CURWOOD: Overcoming the Superfund stigma, next time on Living on Earth.

And don’t forget that between now and then, you can hear us anytime and get the stories behind the news by going to loe.org. That’s loe.org. And while you’re online, send your comments to us at letters@loe.org. Once again, letters@loe.org.

Our postal address is 8 Story Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138. You can reach our listener line at 800-218-9988. That’s 800-218-9988. CDs, tapes and transcripts are $15.00

[SOUNDS OF CRICKETS AND FROGS]

CURWOOD: Before we go, a few more crickets, some frogs and other various nocturnal creatures that live near the foot of Mount Bosavi in Papua, New Guinea. Steven Feld made this recording he calls "Nulu Night."

[SOUND: Earth Earth, "Nulu Night" (Earth Ear, Fall, 2001)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation, in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Jennifer Chu and Cynthia Graber, along with Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Jessica Penney and Carly Ferguson. Special thanks to Ernie Silver.

We had help this week from Andrew Strickler and Nicole Giese. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental Sound Art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include: the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for coverage of western issues, the National Science Foundation, supporting environmental education, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living On Earth’s expanded internet service, the Educational Foundation of America for coverage of energy and climate change, the Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation for reporting on marine issues, the W. Alton Jones Foundation, supporting efforts to sustain human well-being through biological diversity, www.wajones.org, the Oak Foundation, supporting coverage of marine issues, and the Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth