February 25, 2005

Air Date: February 25, 2005

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Amazon Deforestation

View the page for this story

Shortly after environmental activist Dorothy Stang was murdered in Brazil, the country's president Lula da Silva pledged to step up law enforcement to stop the violence. He has also agreed to create two large reserves in the area where the 74-year-old nun lived and worked. Host Steve Curwood talks to Outside Magazine contributing editor Patrick Symmes about Stang and the future of the Brazilian Amazon. (10:00)

Listener Letters

View the page for this story

We dip into the Living on Earth mailbag to hear what listeners have to say. (02:30)

Cleaner Truckin'

/ Ingrid LobetView the page for this story

More than a million truck drivers in the United States spend most of their time living in their cabs. To keep warm or to keep cool, most have to idle their engines, which spew particles and harmful gases. But, as Living on Earth's Ingrid Lobet reports, a Tennessee inventor has come up with a solution that's proving very popular in truck stops across the nation. (09:30)

Exploring the Ocean's Geology

View the page for this story

Living on Earth host Steve Curwood talks with scientists at sea in the eastern Pacific Ocean. With the help of a submarine named Alvin and a robotic craft called Jason II, they're exploring an underwater canyon called Pito Deep and hope to uncover some of the mysteries of the ocean floor. (08:30)

Emerging Science Note/Can You Hear Me Now?

View the page for this story

Living on Earth's Jennifer Chu reports that hearing loss could be all in the brain. (01:30)

Polar Bear Politics

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

An environmental group says polar bears belong on the endangered species list because global warming is melting their habitat. Conservatives in Congress say the enviros are turning the polar bear into a political poster child. Jeff Young reports from Washington. (04:40)

Big, Bad Wolf?

View the page for this story

Ever since America's colonization, wolves have gotten a bad rap as vicious, relentless predators. Host Steve Curwood talks with author Jon Coleman about the psychology behind the big bad wolf, and about his new book, "Vicious: Wolves and Men in America." (09:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Patrick Symmes, Emily Klein, Jeff Karson, Jon Coleman

REPORTERS: Ingrid Lobet, Jeff Young

NOTE: Jennifer Chu

(THEME MUSIC UP AND UNDER)

CURWOOD: From NPR - this is Living on Earth.

(THEME)

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. There are millions of trucks on the nation's highways these days-delivering goods to communities big and small. But the diesel fuel most of them burn leaves the air heavy with pollution that is hazardous to public health.

CACKETTE: There are about 2900 premature deaths from the emissions of diesels....and 600,000 lost workdays every year in California alone.

The good news: one man has found a way to clean the air by making it easier for diesel truckers to shut off their engines more often.

Also, why the wolf has been reviled for so much of history.

COLEMAN: Bad times for humans are often good times for wolves, so if you have extended periods of war or disease or plagues, you would actually have wolves out eating humans.

CURWOOD: The dark side of humans and wolves, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Amazon Deforestation

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

When Amazon rainforest activist Chico Mendez was murdered outside of his home sixteen years ago, many thought his death would lead to reforms that would slow the destruction of the Amazon and end the corruption aiding its decline.

But even Chico Mendez, himself, was skeptical that his own death would change anything. This is actor Raul Julia playing the leader of the Brazilian rubber tappers union in the 1994 movie "The Burning Season."

FILM: If a messenger came down from heaven and guaranteed that my death would strengthen our cause, it might be worth it, yes. But it's not with big funerals that we're going to save the Amazon. I want to live.

CURWOOD: Recently, the funeral of another leading activist put hope into the minds of Brazilians and others around the world that the Amazon would benefit at last from the death of a martyr. This time the victim was seventy-four-year-old American nun Dorothy Stang who was shot six times at close range. Immediately after her slaying, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula Da Silva said he would establish more than 20 million acres of protected reserves in the forest regions where Sister Dorothy had lived and worked. He's also vowed to stop the violence against rural workers. Since Lula took office in 2003 Amazon deforestation has not only continued but it's been on the rise.

Joining us now is Patrick Symmes who is a contributing editor for Outside Magazine. Welcome, Patrick.

SYMMES: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Now, Patrick, several years ago you wrote a feature story called "Bloodwood" for Outside Magazine. It's about the illegal logging trade in Brazil. First, set the scene for me here. Now the government has pledged to set up a nine million acre reserve. What area are they talking about?

SYMMES: I've been in both of the reserves that make up that more than nine million acres. It's one of the main tributaries to the Amazon to the south, deeply wild region, full of meandering rivers, very subject to changes in the rainy season and the dry. The upperlands, the larger part of the reserve is home to a lot of Kaipo Indians and other groups, and logging has been encroaching in it bit by bit and people have been settling around the edges of it and logging companies are starting to...have been coming in for years now and stealing mahogany and other valuable trees off land that really doesn't belong to anybody. It's public land or Indian land. Some landowners claim it. So you have a lot of land conflicts over who gets the profits from abusing the Amazon and it's never the poor farmers who are the first ones who come in driven by a sense of hunger.

CURWOOD: Hmmm. How much is a mahogany tree worth?

SYMMES: By the side of the water in the upper Jingo watershed it's probably worth five to 20 dollars depending on how big it is, which would usually be paid for in sugar and gasoline to whichever farmer or poor person cut it down. By the time it gets to a sawmill, it's worth a couple thousand dollars. When it's cut into boards and shipped down to one of the great port cities like Manaos or Belém, it's worth probably a hundred thousand dollars. By the time it gets to a furniture showroom on Madison Avenue in New York, I've seen mahogany sideboards priced at 25 thousand dollars apiece. So that tree, in the end, could be worth a million dollars.

CURWOOD: And the guy who cuts it down gets maybe 20 bucks.

SYMMES: Sugar and gasoline.

CURWOOD: Now, how meaningful is this declaration by the Brazilian government to set these areas aside as a reserve?

SYMMES: It's very important as a watershed event in Brazil's relationship with the Amazon. The national project has always been to develop the Amazon, and Brazil has had a rise in its own environmental movement getting stronger; but the Amazon has always been out of bounds, a place that was lawless where politicians and businessmen set the agenda and there was impunity. Now that impunity, at least in theory, has been put on the table and is gonna be ended.

CURWOOD: To what extent is the government gonna back up this declaration with real enforcement? Boots on the ground with rifles?

SYMMES: Well, they sent a lot of soldiers into the Amazon immediately to try to make a show of force and a symbolic step, but that doesn't change things over the long run, just as these two reserves, as large as they are, in fact, they're just a tiny, tiny piece of the Amazon. The question is, there would need to be more reserves and more planned and are also being logged by companies coming in from overseas that looking for a quick return on some investment funds.

CURWOOD: This is nothing new, I mean, the Chico Mendez story from what? 1988 is, perhaps, the most famous of these.

SYMMES: That's right and look how little has really changed. What's quite frightening to me is, you hear headlines from time to time about the Amazon disappearing at a greater or lesser rate and what does this mean? The real story is that over time the rate has stayed just the same. Year after year, decade after decade. We have failed to stop or even really decrease deforestation. It just carries on forward. Nothing has changed since the days of Chico Mendez.

In theory, now, with a more democratic Brazil, a larger, popular environmental movement in the country, there is room for real change now in asserting that the Amazon must be governed. That logging must take place under a system with permits that are actually enforced and mean something.

CURWOOD: So, the Amazon has this history of activists trying to protect the forest being killed. Most recently Dorothy Stang, a nun. Tell me, what happened in her case? Where did this happen and what exactly did happen?

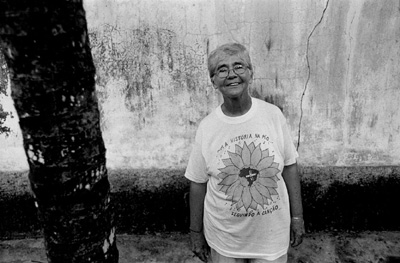

Dorothy Stang, an American nun, helped organize peasant farmers against illegal logging in the Brazilian Amazon. She was murdered on February 12, 2005. (Photo © Seamus Murphy)

CURWOOD: What was she like, you spent a fair amount of time with her?

SYMMES: She was a small very powerful woman. One of these people, she was sort of round, and not that imposing a figure. A genial, great smile, and sort of flashing eyes. Gray hair and just a great sense of humor and singing and you know, went around, she didn't wear a habit. She was wearing a t-shirt with an environmental sort of social struggle slogan on it. And she clearly had a sense that there was a tragedy taking place for Brazilians and for the people like her who were defending them and she was keenly aware that it was dangerous work. She made light of it, but you could see the pain in her eyes. She said oh, you know, she had gotten all these death threats and she said, "well, a dog that barks a lot, doesn't bite." But, eventually, they found a dog that would bite.

CURWOOD: The killing of a 73-year-old American nun who, by the way, I would take it could have been killed just about any time, clearly sends a message to the government that the killers don't believe that anyone is in charge, but them. Why do you think that they took this time, now, to do this?

SYMMES: The impunity had been spreading and growing. Previous promises to put an end to assassinations and the murder of land activists had been made and broken. And time after time, those who ordered assassinations, or insisted that a certain person be gotten rid of were left, you know, in their social clubs uninterrupted.

CURWOOD: Why do you think that now after the death of the nun, Sister Dorothy, that things will change?

SYMMES: I think Brazil has changed. Over the last, sort of, 25 or 30 years the big environmental movement in the first world has clamored over the Amazon without having any success at reducing deforestation. The difference now is that Brazil has a big environmental movement. The Brazilians are the ones marching and demanding protection of forests, the honoring of reserves, the rights of the indigenous. That's the only hope for change . I think.

CURWOOD: This does not sound like the easiest place in the world to live. And what is it like for the ordinary people who are there? I've heard stories that people working small areas of land will sometimes get a knock on the door and be told to clear out in a couple of hours because some large land-barren interest wants them out.

SYMMES: That's exactly right. Dorothy Stang was actually killed while walking to a meeting of peasant farmers who had been given an eviction threat by armed gunmen and been told "you have to be out of here in a couple of days." And they were organizing to defend themselves when she was killed. It's important to look away from the one crime of what happened to Dorothy Stang and remember that there are five hundred Brazilians who are living under death threats right now because they are activists in the Amazon.

CURWOOD: Patrick Symmes is a contributing editor at Outside Magazine. Thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

SYMMES: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Since we spoke to Patrick Symmes, yet another prominent Brazilian forest activist has been murdered. Dionisio Ribeiro, who was working to stop poaching and the illegal harvesting of palm trees, was gunned down at the Tingua nature reserve near Rio de Janeiro on February 22nd.

Related link:

"Blood Wood"

Listener Letters

CURWOOD: Time now for your comments.

[LETTERS THEME UP AND UNDER]

CURWOOD: Our round table discussion on the future of environmentalism drew a number of responses. In their essay, Michael Schellenberger and Ted Nordhaus argue the environmental movement is on the decline. Carl Pope, executive director of the Sierra Club, defended the viability of environmentalism.

David Lillie, who listens to Living on Earth on New Hampshire Public Radio, took Mr. Pope to task. "Carl Pope, like so many liberals, and like so many so-called environmentalists, wants to blame all of the shortcomings of the movement on the "right." Each time you do this you insult a large group of allies and potential allies."

WMRA listener Ken Betts in North Garden, Virginia added, "Concern for the environment is not a liberal or conservative issue. It is the mark of good citizenship and stewardship for future generations, irrespective of one's politics."

WAMC listener Peter Riva writes, "Over the years, as an active environmentalist, I have listened and been dismayed at the professional fund-raisers' use of hyperbole and scare tactics to further what are, admittedly, respectable goals. The only environmental campaigns that have proven successful over the years with the public are those that sought a positive goal, a goal that could be seen, felt and enjoyed."

Some of you also wrote about our story on the continuing battle over drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. In our report, Alaska Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski asserted that the environmental record of Alaskan oil has been stellar.

But Janet MacLean, who listens to KUOW in Seattle, writes, "It is well known that during that thirty years, Alaska experienced the Exxon Valdez oil spill...no one can honestly call the record ‘stellar.' You should have called the Senator on her claim."

Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line any time at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-99-88. Or write us at 20 Holland Street, Somerville, Massachusetts 02144.

[LETTERS THEME SNEAKS UNDER]

CURWOOD: Our email address is comments at loe dot org. Once again, comments at loe dot org. And you can hear our program any time on our web site, Living on Earth dot org. That's Living on Earth dot org.

[MUSIC UP AND OUT]

CURWOOD: Coming up, fresh air for truckers and their neighbors during rest stops. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Tony Furtado & Dirk Powell "Angeline the Baker" Tony Furtado & Dirk Powell (Rounder) 1999]

Cleaner Truckin'

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Clean air advocates are calling on the federal government to do more about older trucks on the road in response to yet another report that shows the harmful health effects of diesel exhaust. The news couldn't come at a better time for one inventor from Knoxville, Tennessee. He's come up with a novel way to cut down on diesel pollution and, as Living on Earth's Ingrid Lobet reports, it all started with a parking ticket in New Jersey.

LOBET: About five years ago in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, A.C. Wilson and his wife Doris had just set up their camper for the evening. They waited for A.C.'s brother-in-law Carl, a long haul trucker, to show up but it was getting late and they were getting hungry.

A.C. WILSON: So, we all went on to dinner without him and came back and he was mad as a hornet. He had been up in the Northeast, Jersey, and had gotten a ticket for parking on the on-ramp and idling his engine.

LOBET: Carl left his truck running because that's the usual way truck drivers keep their cabs warm or cool through nature's extremes. That night, Wilson, a longtime tinkerer, pondered the predicament.

WILSON: I bedded down in my motor home. And I was layin' there and I thought--why can I not do this for a trucker? Because I've got all the--cablevision, I've got heat and air on my rig but I've got to come up with a way to put heat and air conditioning into a parked truck.

LOBET: That night, Wilson got his idea. Picture a car vacuum hose. But instead of sucking air, the hose ends in a touch screen panel and vents that deliver warm or cool air, and also telephone, satellite TV, and fast internet. The next morning, he showed his brother- in-law the sketch and soon found himself talking to truck stop companies.

WILSON: They were very receptive to it, and wanted to know where we'd been the past 20 years, but that was how it was actually founded.

LOBET: Today, Wilson's company Idleaire makes a device that fits snugly into most truck windows. Drivers can find the connections at truck stops in ten states. The company has received clean air awards from the Environmental Protection Agency and the state of California. And some major trucking companies, like National Freight and Continental Express, have signed on. They pay Idleaire $1.40 an hour, but save two dollars every hour on diesel fuel.

[TRUCK WARMING UP, RADIO NOISES]

PORTER: Hello My name is Jerome Porter. I drive for Continental Express.

LOBET: Jerome Porter says he likes life on the road. He better. For most of the month, his truck is his home.

PORTER: Livin' in my truck, I don't have a problem with it. You know, I make pretty decent money. I got a comfortable bed back there, matter of fact I have two beds. I have a TV. I have a DVD player, a VHS player, along with my laptop computer, so I can always find something to do, to occupy my time.

LOBET: But to keep his cab warm or cool, he needed to idle.

PORTER: But you get up on the East Coast and New York they don't like big trucks to idle their trucks, you know. You mainly have to have a heated blanket or idle your truck for, you know, 15 minutes to an hour. But if the police come by, you have to shut your truck off otherwise they will ticket you.

LOBET: Then, one day, Porter pulled in to a truck stop with Idleaire hookups.

PORTER: I said to myself, "well, lemme see what it does. I'm not going to pass judgment yet." And once I felt how cold the air could get without me idling my truck, I'm like -- "oh, I'm sold (laughs)." I wasn't caring about the TV, the Internet service, uh-uh....just the air, heh-heh.

LOBET: Idleaire was initially aimed at alleviating the sweats and chills of life on the road. But it turns out the inventor stumbled on a partial solution for one of the nation's biggest air problems -- diesel exhaust. The situation is so serious 21 states make truckers limit their idling. California is the most recent. Tom Cackette is deputy executive officer at the California Air Resources Board.

CACKETTE: Here, in California, we have over a million diesels operating and they cause a lot of smog. They are responsible for about half of the summertime ozone smog-forming emissions.

LOBET: Half of all nitrogen oxide emissions in summer. But that includes diesel equipment and driving. What about just idling?

CACKETTE: Well, the idling is about 50 tons per day of NOX and about one ton per day of particulate. That's about the same smog forming emissions as 1.75 million cars would put out.

LOBET: Truck engine makers are retooling and they'll soon sell rigs that burn 97 per cent cleaner. And the Bush administration is cracking down on tractors and construction equipment diesels. That still leaves the trucks already on the road. Recent studies in California show even commuters who spend short periods in heavy traffic are getting significant exposures to diesel exhaust.

CACKETTE: We have characterized what the impact of these diesel emissions are and it is quite stunning. There's about 2900 premature deaths every year from the emissions of diesels. There's about a quarter of a million asthma attacks that occur as a result of diesel emissions and over 600,000 lost workdays every year in California alone.

LOBET: So when Idleaire came along and allowed trucks to turn off, regulators took notice. They started paying Idleaire to install facilities, in some cases defraying the company's capital costs.

[TRUCK SOUNDS ]

LOBET: At a truck stop in Fresno, California, Idleaire employee Courtney Bowman shifts her weight from foot to foot to keep warm as she waits for her chance to persuade a weary trucker to give Idleaire a try.

[AIR BRAKES]

BOWMAN: We are a company that provides air conditiong, heat, plug-ins, phone, satellite TV and internet.

MAN: Yes, ma'am.

BOWMAN: This is a window adapter here that you will buy which is ten dollars. That's yours to keep. We give you a membership card with ten dollars already on it. That'll hold you for, like, seven hours. After that, it's a dollar 40 an hour.

MAN: Okay.

BOWMAN: Here you can get on the internet and browse. I'm not going to hold you up too long. I know you have got to go. Nice to meet you. Happy holidays.

MAN: Thank you, ma'am. Appreciate it.

LOBET: Bowman gets about 30 seconds to make her pitch . It's too early in the day for much business. But a few who have hooked up are happy to say why. Daniel Johnson drives out of Rolla, Missouri.

JOHNSON: I wish there was more Idleaire. I'd pull into it every time I can, you know. If we turn off our truck in the summertime we get too hot because of the heat coming off of the engine and the transmission and, you know, heat coming through the cab from the sun. And in the wintertime, it's just unbearably cold really, really fast. And, you know, you really do need to keep more of a constant temperature so you don't get yourself sick.

BIRD: I hate pulling into a truck stop, trying to get some sleep and somebody next to me decides he's gonna run his rig all night.

LOBET: Jeff Bird drives out of Sacramento.

BIRD: It's annoying and it's expensive and it's polluting the air and these are already extremely gross polluters . But everybody in America wants their product, so they're...it's kind of a give and take. You're gonna give up some clean environment so that everybody can have their Gucci handbags. We, Americans, are consumers of everything. From popcorn to Gucci.

LOBET: But, as much as Jeff Bird loves this service, he scratches his head about Idleaire's business model.

BIRD: Like, I pull in and I used it for three hours. That's only five bucks, I don't know, maybe the numbers crunch right, but to me it didn't seem like it would.

LOBET: He has a point, says Linda Gaines, a physicist and diesel idling guru at Argonne National Laboratories Center for Transportation Research. Gaines says selling devices that let truckers shut of their engines and still have power should be a profitable game, and several companies are making a go of it. But she doesn't think Idleaire wins in an even race.

GAINES: The installations are very expensive. They require a very large staff to run them. And the revenues from just the basic services are rather low. And so, what we see is that a lot of the initial installations have been funded by government grants but we don't know how they're going to make it as a long-term viable business without government subsidies.

LOBET: Potential competition includes small diesel engines, and a fuel cell power unit developed by Freightliner and UC Davis. Also some newer trucks are being built so they plug in where power is available. A.C. Wilson, Idleaire's low-key founder, says his model is competitive.

WILSON: We're not out here promoting anti-idling or anything but we are here to promote a solution and we think the communities and the drivers themselves would really like.

LOBET: And for now, that's one way of making a dent in the nearly one billion gallons of diesel fuel burned each year by idling trucks. For Living on Earth, I'm Ingrid Lobet.

[MUSIC: Ry Cooder & V.M. Bhatt "Longing" A Meeting by the River (Water Lily Acoustics) 1993]

Exploring the Ocean's Geology

CURWOOD: Our next guests are a couple of scientists who have hit bottom. The bottom of the sea, that is. In their research vessel the Atlantis, anchored just west of Easter Island in the Pacific Ocean, they are exploring Pito Deep, an underwater chasm, to get a glimpse into the geology beneath the ocean floor. The research submarine Alvin and a robotic called Jason II, allow a small crew to travel about two and a half miles beneath the ocean surface to go into Pito Deep and take pictures and collect samples of rocks and lava from the earth's crust.

Emily Klein is co-chief scientist of the expedition and a geology professor at Duke University. She joins us now from aboard the Atlantis.

Professor Klein, welcome to Living on Earth.

KLEIN: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Now, what's a group of geologists doing out in the middle of the ocean?

|

Alvin is launched from the Atlantis. (Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.) |

KLEIN: Well, 70 percent of the earth's crust is covered by water and so a great deal of geologic interest on the earth takes place on the ocean bottom.

CURWOOD: You're out at this deep underwater chasm, described as an underwater Grand Canyon, called Pito Deep. What actually is Pito Deep? KLEIN: Pito Deep is an unusual place in the ocean where, if you can imagine that, imagine the ocean crust being something like a layer cake. Normally, you can only see the top of the cake, that is to say, the icing, but we're particularly interested in looking deeper into that cake into the known layers of the igneous crust below the surface and normally you can't see that. But there are certain places in the ocean where due to some unusual tectonic forces, in this case, a large fault, a rift, has opened up a deep, wide chasm that allows us to look at the deeper layers of this cake or this ocean crust. And the Pito Deep is one such place. CURWOOD: So, these places are found only in the ocean? There's no place on land that you can see this kind of formation? KLEIN: There are rifting places on land, certainly. East African Rift is one of those places, but the ocean crust is unique. It's different from the continental crust, entirely different in chemical composition and in structure. And so, if we want to look and study the ocean crust we have to go to the oceans. CURWOOD: Professor Klein, your research ship, the Atlantis, is using two types of vehicles to explore the ocean floor and in a few minutes we're gonna talk with a scientist in Alvin the submersible, but there's also Jason, a robotic. Tell me about the differences between the two, what they're used for, what they look like.

|