July 19, 2013

Air Date: July 19, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Risks of Oil Trains

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

A train laden with crude oil recently derailed and exploded in a small town in Canada, leaving 50 people dead or missing. Use of trains to transport oil has increased dramatically in the last few years as fracking technology makes oil more available in areas without pipelines, such as North Dakota. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on the relative safety of trains versus pipelines to move oil. (05:15)

Oil Train Concerns in the Pacific Northwest

View the page for this story

Plans are underway to build terminals in the Pacific Northwest to transport coal from Wyoming as well as North Dakota's oil from trains to refineries. Ashley Ahearn of the public media collaborative EarthFix tells host Steve Curwood that the more local residents learn about them, the less popular the proposed fossil fuel terminals. (07:35)

Climate Disruption and Sea Level Rise

View the page for this story

New research from Germany's climate research center, the Potsdam Institute, finds that for every degree Celsius the temperature increases, sea levels will rise about 7 feet. Anders Levermann, lead researcher on the study, tells host Steve Curwood this dramatic sea level rise will take place over the next 2,000 years. (06:30)

Hult Prize Competition

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

The Hult Prize challenges students to create a workable business solution to a global problem and win a million dollars to make it happen. Living on Earth's Helen Palmer reports on one of the regional finals, won by a Canadian team with a plan to grow, process, and sell edible insects to empower low income urban communities. (09:30)

.jpg)

Hunting For Edible Insects

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

The UN's Food and Agriculture Organization published a report advocating eating insects as a way to reduce food insecurity. Dave Gracer has been running an edible bug business called Small Stock Foods since 2009. Living on Earth's Emmett FitzGerald joined him for a bug hunt in Rhode Island. (09:00)

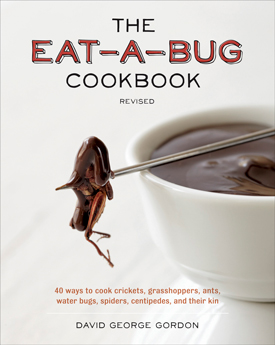

Eat-a-Bug Cookbook

View the page for this story

Not only should we consider eating insects for environmental reasons; they’re also tasty and healthy. Author David George Gordon just released an updated version of his Eat-A-Bug Cookbook, featuring recipes for crickets, grasshoppers, ants, spiders, centipedes, and their kin. He shares such recipes as Fried Green Tomato Hornworms and Three Bee Salad with host Steve Curwood. (09:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Anders Levermann, David George Gordon

Reporters: Bobby Bascomb, Ashley Ahearn, Helen Palmer, Emmett FitzGerald

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. As the world warms and the ice melts, civilization will face some dramatic changes in the level of the oceans.

LEVERMANN: On the long term, and we're really talking about millennia here, we expect a sea level rise of two meters for each degree of global warming that we cause.

CURWOOD: How to prepare for seas at least 15 feet higher. Also, comparing the relative safety of pipelines and trains to transport oil, and why some advocates say we have to get over the aversion to insects...and eat them.

GRACER: Look at the future, look at what's coming our way. It's really kind of terrifying. 9 billion plus people by 2050, which is not that far away, and none of the experts have explained where all that food is going to come from.

CURWOOD: Grasshopper snacks and Katydid crisps. We'll have those stories and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic smoothies, yogurt, and more.

The Risks of Oil Trains

Pipelines transport the vast majority of US oil. (US House of Representatives)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The recent spate of oil transportation accidents is fueling debate over how we should be moving fossil fuels. A messy tar sands oil pipeline spill in March in Arkansas was followed by the July 6th derailment of an oil train in Canada, which incinerated the center of a small town in Quebec and left 50 people dead or presumed dead. The train was bound for a refinery in New Brunswick, loaded with 72 cars full of crude oil from the fracking boom in North Dakota. These disasters raise questions about the relative safety of trains versus pipelines to transport oil, and Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb has been investigating.

BASCOMB: The use of trains to transport oil has skyrocketed in the US - up 160 percent in the first quarter of this year compared to last. A large part of that rise is due to the development of the Bakken shale formation in North Dakota. In April of this year, North Dakota exported nearly 800,000 barrels of oil a day compared to just 80,000 barrels a day a decade ago. Three quarters of the crude left North Dakota by train and as fracking technology continues to make the oil more available that amount is only expected to go up. That’s according to this statement from the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers.

ANNOUNCER: The tremendous expansion of U.S. oil production and the lack of adequate infrastructure due to a costly permitting process ensure more use of rail to ship crude oil east and west. To meet the demand, producers have made significant investments in the infrastructure necessary to transport crude oil by rail. Rail safely and capably transports thousands of people and commodities every day without incident.

BASCOMB: When it comes to the safety record of transporting oil - trains and pipelines are essentially the same, says Brigham McCown, the former head of the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.

The use of trains to transport oil is rising as more domestic oil is tapped in areas without pipelines, like Nebraska. (US Geological Survey)

MCCOWN: When you look at total volume, pipelines do have a little bit of an edge in safety but, we’re splitting hairs in thousandths of a percent at that point.

BASCOMB: Both trains and pipelines have a safety record of better than 99 percent. However, because pipelines transport 96 percent of oil in the US, they are responsible for many more spills each year. Just the day before the Canadian accident, for example, a pipeline in Montana spilled 25,000 gallons of gasoline on the Crow Indian Reservation. The Association of American Railroads says in the last decade more than 470,000 barrels of oil were spilled by pipelines versus just over 2,200 spilled by trains. And there’s another way pipelines are superior, says McCown, and that’s carbon emissions.

MCCOWN: A pipeline is like a one way street; when you get to the end there’s no return trip required. When you look at the carbon intensity of a locomotive, even though they are very efficient, you have to make that 1,200 to 1,500 mile trek, and then you have to turn the train around and bring the train back.

BASCOMB: Trains traditionally made that trek carrying coal but demand for coal is falling as natural gas becomes cheaper to extract. So the railroads are happy to have oil companies as a new customer. But McCown says it costs much more to transport oil by train than pipeline.

MCCOWN: For about a thousand mile journey a pipeline will add about $5 per barrel on to the cost and railroad would be $15 for the same amount.

BASCOMB: So pipelines are slightly safer, cheaper and produce fewer carbon emissions - all arguments cited by supporters of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline to bring Canadian tar sands oil to Gulf Coast refineries. The State Department report on Keystone calculated that the Alberta oil would be extracted even if Keystone isn’t built. The oil company TransCanada would just transport its oil by railroad. But Kate Colarulli, director of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Oil campaign says that argument doesn’t hold water.

COLARULLI: The State Department’s analysis has been roundly criticized for being out of date and not based on current market information. Just recently Goldman Sachs, they’re one of several different industry groups - financial industry and oil industry groups - that have come out and said that Keystone is actually a lynchpin for tar sands expansion. Rail is not a viable alternative for technological and economic reasons.

BASCOMB: And if rail transit is not a viable alternative to Keystone, critics argue that the pipeline project is essentially dead.

COLARULLI: Because the tar sands have been shown to have much greater climate consequences, it would be a mistake to continue to invest in expanding the tar sands.

BASCOMB: Indeed Colarulli says choosing between oil pipelines and oil trains is the wrong approach.

COLARULLI: I worry about some of the news reports I see that are suggesting we have to choose between pipeline disasters and rail car disasters when in truth we have the technology to dramatically reduce our oil use and thereby reduce the harm our reliance on this fuel causes.

BASCOMB: But following the disastrous runaway train in Canada, authorities are reevaluating the safety of moving oil by train.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration

- Association of American Railroads

- Sierra Club

[MUSIC: Meshell Ndegecello “Dead End” from Weather (Naïve Records 2011)]

Oil Train Concerns in the Pacific Northwest

A train carrying oil pulls into an oil terminal. (photo: bigstockphotos.com)

CURWOOD: Concern over the climate is also feeding the debate over fossil fuel transport. In the Pacific Northwest there's controversy over proposals to carry massive amounts of coal by rail from Wyoming to new export facilities in Oregon and Washington. And now the train tragedy in Quebec has officials rethinking plans to lease and develop a new deep water oil terminal for the west coast. Ashley Ahearn of the public media collaborative EarthFix has been following these developments and is on the line from Seattle. Hey, Ashley, tell me about these plans and what's going on now.

AHEARN: Well Steve, the same oil that was in the train that exploded in Quebec is also moving through the Northwest. This is oil from the Bakken oil fields of North Dakota. And there are now 11 places in Washington and Oregon considering building terminals that would take the oil off of the trains and put them onto ships bound for west coast refineries. So this is now small change, when we look at capacity here. When you combine all 11 places, you’re looking at 700,000 barrels of oil moving through the northwest every day. And to give you a sense of perspective, Keystone XL is 830,000 per day.

So we’re definitely within the same ballpark here. And the largest of the proposed terminals in the Northwest could be built in Vancouver, Washington, and this terminal would handle up to 360,000 barrels per day. That would mean 70 trains coming through the Columbia River Gorge every week carrying that oil to and from the Bakken oil fields. So the tragedy in Quebec has definitely given the port commissioners pause as they consider the lease to have this terminal built, that’s for sure. But that being said, my sources there say they’re still optimistic that the terminal will go forward, and they’re going to be having a vote later this month and potentially postpone the review a little bit, but there’s a very good chance that that terminal could still be built.

Trains carrying oil are increasingly making their way from North Dakota oil fields to West Coast oil terminals. (Photo: Bob Shand)

CURWOOD: Ashley, but even if oil could be carried and a terminal developed safely, the whole notion of that kind of development seems to be at odds with the pledge that President Obama gave about Keystone, regarding oil, in his climate change speech on June 25.

OBAMA: Allowing the Keystone pipeline to be built requires a finding that doing so would be in our nation’s interest. And our national interest will be served only if this project does not significantly exacerbate the problem of carbon pollution. [APPLAUSE] The net effects of the pipeline’s impact on our climate will be absolutely critical to determining whether this project is allowed to go forward. It’s relevant.

CURWOOD: But the President’s views may not be so relevant in the northwest when it comes to the coal export question. How was Obama’s climate plan received there?

AHEARN: Well, you hear a lot of applause on that recording, and there was a lot of applause in the environmental community out here as well. But I think there’s a really interesting angle of his speech that’s missing, something that people in the northwest are also watching, and that is this export of fossil fuels through the northwest. When you talk about the potential - if three proposed terminals are built out here - of doubling US coal export capacity. There’s no mention of that in Obama’s climate plan anywhere. What are CO2 impacts of exporting that coal? And potentially that oil as well, as we were just talking about.

A coastal oil terminal. (Photo: Bigstockphotos.com)

So it’s great for Obama to make a statement about what are the potential impacts to Americans of something like Keystone XL, but meanwhile, fossil fuels seem to be sneaking out the backdoor of the country, and the President is making these lofty statements, but we’re not really hearing that in terms of any sort of consideration of climate change in the review of these proposed export terminals in the Northwest. And most recently, the Army Corps testified on this issue before a House subcommittee, and the representatives said that indeed, no, climate change is not going to be factored into the review of the largest coal export terminals proposed for the United States. This is Jennifer Moyer with the Army Corps of Engineers.

MOYER: The appropriate application of our regulations have led us to the conclusion that the effects of the burning of the coal in Asia or wherever it may be is too far removed from our action to be considered as an indirect effect or a cumulative effect of our action itself.

CURWOOD: That’s Jennifer Moyer of the Army Corps of Engineers. And what she’s saying seems pretty clear, but I’m confused as to the science, because any molecule of CO2 anywhere adds to climate change. How was that response from the Corps received in the northwest?

AHEARN: Well, first of all, you’re right, Steve, any molecule does contribute to global warming. And Rep. Waxman of California fired right back at Jennifer Moyer and said, what about the fact that the Army Corps is responsible for the waterways of the United States, and if you’re dealing with sea level rise, that’s arguably already making your job harder around the country when you look at places like New Orleans, for example. And here in the northwest, the Army Corps statement was a real blow to environmental groups who have been watching the coal export debate. However, as you might imagine, it was received very well by the proponents of coal exports in the Northwest.

One interesting thing though that’s emerged from my sources, is that the Army Corps is overseeing these coal export projects as a co-lead agency with the State Department of Ecology. And the State Department of Ecology was not consulted before the Army Corps made this announcement before Congress, that they were not going to consider climate change in their review of the coal export proposals. And so far in the review process, the public has submitted thousands of comments in the pre-scoping process to say, yes, we want climate change considered in the proposed export terminals. And so, for the Army Corps to make this announcement without talking to their co-lead agency is a little bit of a shot across the bow, and it will be interesting to see how these two agencies work together to oversee these proposed coal export terminals. And, Steve, I’ve been taking a close look at the climate change implications of these coal export terminals. And one of my sources is Dan Jaffe, he’s an atmosphere scientist with the University of Washington. And he says, make no mistake, the climate change implications need to be taken into consideration here.

JAFFE: If we don’t consider the climate impacts from burning coal, whether it’s here or somewhere far away, pretty much the climate game is over and we lost.

CURWOOD: That’s Dan Jaffe of the University of Washington. Ashley, tell me, what’s the mood of the public about these projects, especially the coal terminal projects?

AHEARN: This has been a hugely divisive issue. It’s really interesting traveling through towns along the railways, especially along the I-5 corridor that runs up Puget Sound. This is the route of many of the coal trains that will be heading to the largest proposed coal export terminal, and you see signs in people’s yards, both pro and against. And EarthFix has commissioned independent surveys, public surveys, to try and get a sense of what the general public is thinking about these coal export terminals. And back in 2012, 55 percent of people actually supported the coal exports. But in a most recent survey we did in June, 41 percent support them. So we’re seeing a dip in the public support for coal exports in the Northwest. And interestingly enough, when people were surveyed back in 2012, people said the more they knew about the coal export terminals, the less likely they were to support the proposals. So that shift may be already showing up in our numbers if you look at the results from 2013, and then look back at the results for 2012. It’s a really interesting debate that’s only going to heat up more as the review process continues here in the northwest, Steve.

CURWOOD: That makes things difficult for coal, and of course, for oil. That horrific accident also must have the public concerned.

AHEARN: Yes, I think when you combine these two, and you look at potential impacts to rail infrastructure and traffic, as well as safety in the Northwest, you know the climate change story is the big picture story. But there’s some very real local impacts that people are following, and starting to get a little more concerned about in this region.

CURWOOD: Ashley Ahearn is with the public media collaborative, Earthfix in Seattle. Thank you so much, Ashley.

AHEARN: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- EarthFix

- Ashley Ahearn

[MUSIC: Russell Malone “Mandela” from Playground (MaxJazz Records 2004) Happy 95th Birthday Nelson Mandela]

CURWOOD: Coming up...15 feet and counting, the unnerving amount of sea level rise that's inevitable with just two degrees of global warming. That's next on Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Acoustic Alchemy “Jamaica Heartbeat” from GRP 30: The Digital Master Company 30th Anniversary (Verve Music 2012)]

Climate Disruption and Sea Level Rise

Meltwater drained off a glacier in Greenland reveals ice blue walls.

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - the IPCC - is near to completing its fifth assessment on the potential environmental and socio-economic effects of global climate disruption. But in the meantime, there's a new study just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, led by a team from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany. This new research quantifies exactly how much sea level will rise due to global warming over the very long term. Anders Levermann is the lead author of the report and he joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

LEVERMANN: Hello.

CURWOOD: So, how much sea level rise are we looking at as a result of climate change?

LEVERMANN: On the long term, and we’re really talking about millennia here, two thousand years is what we looked at. We expect sea level rise of two meters of each degree of global warming that we cause, for example, by the emission of carbon dioxide and methane.

CURWOOD: That’s on the order for us Americans of about 7.5 feet.

LEVERMANN: Yes.

Surface meltwater disappears in Greenland (NOAA)

CURWOOD: But if we’re looking at, say, a two degrees centigrade rise as in temperature over the next 100 years, that would mean on the order of 15 feet of sea level rise.

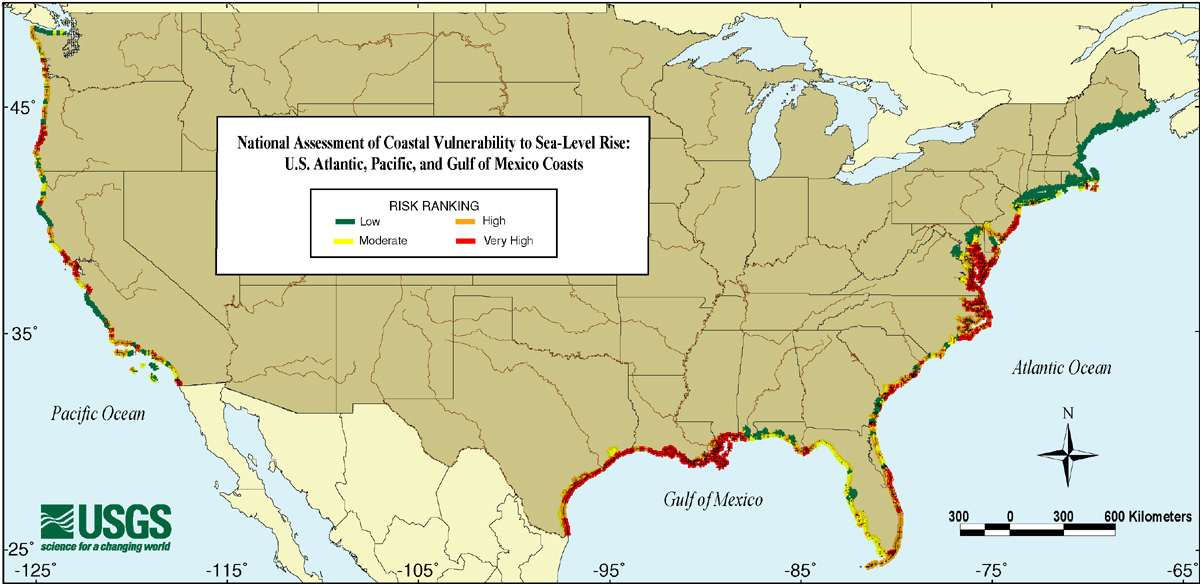

Areas at risk of sea level rise in the US (US Geological Survey)

LEVERMANN: But not within the next 100 years. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which is going to publish its next assessment report by the end of the year - and of which I’m a lead author - is generally focusing on the next 100 years. And the sea level projections that we obtain for different climate scenarios range from 20 centimeters and two meters. For a warming of two degrees, we expect on the long term, a sea level rise of about four meters and more, but this is not going to occur within the next 100 years. It’ll take a long time for this sea level rise to occur.

CURWOOD: What are exactly the factors causing the sea to rise?

LEVERMANN: There are four main contributors to sea level rise. One is obviously the thermal expansion of the oceans. Warm water simply takes more room, and that’s why the ocean is rising when it’s warming. And the others are all glacial in the sense that ice is melting or getting into the sea in from icebergs. And there’s mountain glaciers, which are shrinking at the moment but have half a meter of sea level equivalent stored in them only. And then there are the big ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica, and these have huge amounts of ice, equivalent to about 60 meters of global sea level rise.

CURWOOD: Do your projects show the rise in sea level equally distributed around the world’s oceans? Or do you expect to see more of a sea level rise in some places than others?

LEVERMANN: If you take into account the ice loss from Greenland and Antarctica, both have the effect the tropics are going to rise over proportionally; they’re going to get higher than the global mean while the higher latitudes are going to be slightly less elevated.

CURWOOD: And why is that? Temperature?

LEVERMANN: No. It’s actually because of the dragging force of the ice masses, which are vanishing. The ice is pulling the water towards itself. On Greenland, for example, but also on Antarctica. Similar as the moon is pulling the water on Earth towards itself and therefore cause the tides, right? In a similar fashion, Greenland is pulling the ocean towards the Greenland ice sheet. When you reduce the Greenland ice sheet, you reduce the drag, this pulling, and therefore, sea level is dropping in the vicinity of Greenland, but because there’s more water altogether - it has to rise somewhere else even stronger and this is generally in the tropics.

Anders Levermann is a professor at the Physics Institute of Potsdam University. (Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research)

CURWOOD: Now, another expected effect of climate change includes more large storms like hurricanes. I would think even a small rise in sea level could be significant when you’re talking about a major hurricane or a tropical cyclone.

LEVERMANN: Yes, yes. We know this actually already. This has been computed for the tropical storm Nargis that entered Myanmar, former Burma, in 2006, where people calculated that it went much further inland because of the additional 0.2 meters of sea level rise that we have seen in the last century. Now other studies show that if you elevate sea level around Manhattan by a meter, then the storm surge that you now expect every 100 years to occur would then occur every three to four years. So you can see that there’s a strong non-linear behavior here, so you get much more floodings than for even a small amount of additional sea level.

CURWOOD: 2,000 years seems like a long time, but it’s about as old as, let’s say, Christianity or even less time than other civilizations and religious traditions. Presumably, hopefully, humans are still around at that point.

LEVERMANN: Let’s hope. Yes.

CURWOOD: What’s the advice you have for us going forward as a civilization?

LEVERMANN: At the moment, I’m looking at a map of the UN cultural heritage sites on the planet, and you see a lot of them are built at the coastline. These world heritage sites are very often much older than 100 years. They are several hundred years old, and sometimes even in the thousands. So if you want to preserve the cultural heritage of society then you’ll want to mitigate climate change to a level where it doesn’t threaten our coastlines. Certain societies, like the small island states in the Pacific, but also countries like the Netherlands, will have to abandon certain regions or elevate them to higher levels. And otherwise, we’ll just have to try to build higher dikes and hope for the best.

CURWOOD: Anders Levermann is the lead author of the report issued in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. He works at the Potsdam Institute in Germany. Thank you so much, sir.

LEVERMANN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Read the Full Report

- Anders Levermann

[MUSIC: Avishai Cohen “Seven Seas” from Seven Seas (Sunnyside Records 2011)]

Hult Prize Competition

(from left) Dr. Stephen Hodges, President of Hult International Business School, Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus, one of this year's judges, and Ahmad Ashkar, founder of the Hult prize. (photo: Halt Global Case Challenge)

CURWOOD: Now, we report on quite a few awards and prizes here at Living on Earth. For instance, the Goldman prize that rewards people who work to counter an environmental challenge or the Macarthur "genius" grants, that often feature extraordinary humanitarians. But we learned of one recently that's rather outside our normal beat but still sounded interesting, so we sent Living on Earth's Helen Palmer to check out the Hult Prize.

PALMER: It all started back in 2009. Ahmad Ashkar, a 22-year-old Palestinian-American was studying at the Boston campus of the Hult international business school.

ASHKAR: And this was following the collapse of the financial markets and really the meltdown on Wall Street, so there was a common mood among business schools that they were the root cause of a lot of the problems that we saw in our financial global economy.

Hult Prize Founder, Ahmad Ashkar. (photo: Halt Global Case Challenge)

PALMER: And that realization, that it was business school graduate types like him that had broken the global economy, led Ashkar to a kind of crisis of confidence. Then in marketing class one day, he was sitting at the back, not paying much attention, and the guest lecturer was Charles Kane, the CEO of One Laptop per Child.

ASHKAR: He talked to us about the ability of turning profits by selling products as they do in looking to solve global education challenges through the delivery of affordable laptop computers, and the 'aha' moment hit me that there is an opportunity of actually doing good, bridging borders and having social initiatives that actually turn profits.

Ahmad Ashkar with the 2011 Hult Prize winners from Cambridge University. (photo: Halt Global Case Challenge)

PALMER: And that revelation led him to found the Hult Prize - a challenge to business school students from around the world to dream up a workable plan to solve a global problem - and create a viable, scalable business at the same time. Ashkar networked, he signed up fellow students, he tapped the Hult Business school alumni from all of the school's five campuses in places as diverse as Shanghai and London. He got the endorsement of President Clinton's Global Initiative, and he managed to create an endowment for an annual million-dollar prize.

ASHKAR: Fast-forward four years, we are the world's largest crowd sourcing platform for social good, and we are the world's largest student competition. There's no initiative in the world that seeks to collectively use the power and wisdom of the crowd to solve social issues.

PALMER: And the Hult competition has taken on huge social issues - education, housing, the water crisis. This year, over 10,000 students set about trying to meet the challenge President Clinton set, to devise a practical way to cut food insecurity and hunger in slums within five years. From all the entries, 268 teams were chosen to compete on the same day in regional finals at one of the cities where Hult business school has a campus - in Shanghai, Dubai, London, Boston, or San Francisco.

The regional winners in Boston from Canada's McGill University. From left - Mohammed Ashour, Zev Thompson, Shobhita Soor, Gabe Mott, and Jesse Pearlstein. (photo: Halt Global Case Challenge)

WOMAN ANNOUNCER: Signore e signori, ben venuti.

MALE ANNOUNCER: Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the fourth Hult Prize regionals.

[APPLAUSE]

PALMER: On a spring day this year, 48 teams competed at the Museum of Science in Boston. Each team presented its solution to the judges in one of five rooms, which each produced a winner. The Atlantic Room crowned the Harvard Business School’s plan to fortify and brand the cheapest rice so it could be sold inexpensively in developing world by slum entrepreneurs.

HARVARD PRESENTER: We want to supply daily rice to targeted slums. More than that, we want to provide almost all of the recommended dietary intake of key vitamins like vitamin A, niacin, iron - and we can do that by fortifying the rice. So. Quantity, quality, accessibility, and affordability.

PALMER: The ideas the winning teams came up with were ingenious and various. For instance, a novel method of food distribution.

[APPLAUSE]

GEORGIA TECH PRESENTER: Our team’s called UbuntuBox, and we’re from Georgia Tech…and we're made up of...

PALMER: The Pacific room's winner was the French business school, HEC Paris. Their plan was to train women in slums to raise fish and greens with aquaponics. Women, they said, prove more reliable.

HEC PARIS PRESENTER: They will be working for us, they will be trained, and they will be paid, and at the end, they receive the training not only on how to operate aquaponics but also on food safety, what is important, what to look for, how they should eat. So it's an entire package, and at the end, they’ll also be able to take home 10 percent of what they produce, of what we produce.

PALMER: The final winning team in the Milan room came from Canada's McGill University with an idea based on breeding and raising crickets in slums. Crickets can eat table scraps, they can be eaten whole, or animal protein from the insects could be used to enrich flour. They call it Power Flour. And they'd harvest the chitin in the crunchy insect exo-skeletons for agricultural and industrial processes. Their scheme provoked plenty of audience response for their two minutes of question time, and questions like, “have you eaten them?”

MCGILL TEAM MEMBER 1: Would you believe we always get that question? So far, none of us have tried them, but our research partners have and say they taste like almonds.

PALMER: And asked someone else, “are they halal?”

ASHOUR: Oh yes, of course. Get Mohammed to answer this question.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHS]

ASHOUR: The answer is yes; if you’re interested I can quote scripture or different schools of thought on the matter. But we’ve actually considered halal, we’ve considered kosher, we’ve considered vegetarians, of course, who simply don’t eat insects of any form, but we still given all of that, I mean we found that there are in fact...

ANNOUNCER: Time!

ASHOUR: Yes.

[PAUSE THEN AUDIENCE LAUGHS, CHEERS, AND APPLAUDS]

PALMER: At that point, the judges went off to weigh up the finalists and decide which team would get to face off with the other regional Hult Prize winners from Shanghai, Dubai, London and San Francisco. And a local a capella group entertained the audience.

[LIVE MUSIC]

PALMER: Finally the judges came back - and Charles Kane, whose lecture as CEO of One Laptop Per Child inspired Ashkar to dream up the Hult prize in the first place - got to announce Boston's winner.

KANE: And without further ado, McGill, you’re going to New York.

[CHEERS AND WHISTLES]

PALMER: That was the sign for everybody to head to the reception - where there were no crickets to eat - but I did find one of the judges. Sheryl Chamberlain works for the EMC corporation, and she said it had been hard to choose a winner.

CHAMBERLAIN: That was the hardest part. It was listening to these amazing young people that have creative ideas and new ways of solving this problem that we’re looking at, making sure we can feed the world. It’s so hard to decide who should come first and make a decision.

PALMER: In the end, Chamberlain said, all the judges agreed on the McGill team and their small cricket farms in the slums.

CHAMBERLAIN: So the idea of taking crickets and using them for a food source going forward, farming those crickets, eating them whole, looking at different ways to use them, because they give protein in a different way that we have not considered before. So it’s really innovative and watch out - there’ll be crickets flying around your town, and we’ll be grabbing them and using them for sustainable food.

PALMER: As for me, I grabbed some members of the winning team.

MOV: I’m Gabriel Mov from McGill MBA.

ASHOUR: I’m Mohammed Ashour, also from McGill’s MBA program.

THOMPSON: I’m Zev Thompson, McGill MBA.

PALMER: And we’re missing a couple…

THOMPSON: Jesse Pearlstein and Shevita Suer.

PALMER: Each of them had taken on a different task to get their plans and presentation together, depending on their expertise, they said. For instance, Mohammed, the team leader, studies medicine as well as business. Shevita is a joint legal and business student. And Zev Thompson had a unique role.

THOMPSON: My role was to disagree with almost anything that anyone said. And just try to provide skepticism to everything, and also I did a lot of scientific research in the background. I mean, really, I think we all did everything. It’s tough to split along the lines like that, but that was my main role.

PALMER: Mohammed was pretty sure he knew what his team had that made it stand out and win.

ASHOUR: I think it’s because we bring together a very complementary set of skills, that we challenge each other within the boundaries of a high level of respect, and that our hearts were really into this, especially as we approached this competition.

PALMER: Now the Canadian team, and the teams from Barcelona, Manila, Cape Town, San Francisco and London that won regional finals in the other Hult school cities, are spending their summer refining and polishing and honing their plans, to make them as air-tight and practiced and perfect and actionable as possible. McGill's Zev Thompson.

THOMPSON: And then at the end of the summer, we pitch in New York to the Bill Clinton Foundation - the Bill Clinton Initiative - sorry. And then the winner of the five teams gets a million dollars to trigger their initiative. But honestly, after having the entire summer to focus on refining our project, whether we win or not, we all are committed to moving forward with this project.

PALMER: And that's part of the aim of the Hult Prize - to spark initiatives that can help solve global problems, even for those teams that don't win a million dollars to make it happen. It's certainly worked for these MBA students and their venture, the Aspire Food Group. So watch out; tiny cricket farms will be coming to slums worldwide soon, providing Power Flour and roasted pepper and lime cricket chips.

For Living on Earth, I'm Helen Palmer in Boston, Massachusetts.

CURWOOD: There’s more on the Hult Prize on our website at LOE.org.

Related links:

- Hult Prize website

- The Hult Prize Finals will take place on the first day of President Clinton's annual CGI meeting on September 23

- The winner’s blog

[MUSIC: The Abbysinians “Satta Dub. The Mandela Version” from Satta Dub (MIDYEA Records 1998)]

CURWOOD; And coming up, putting theory into practice. We get to chow down on crickets and some other creepy crawlies -- and we even have some recipes. So stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Robert Walter: “The Worm” from The Lagniappe Sessions (Royal Potato Family 2013)]

Hunting For Edible Insects

.jpg)

Dave Gracer, armed with a butterfly net, in the parking lot of Snake Den State Park in Johnston, Rhode Island (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. The UN's Food and Agriculture Organization recently published a report that recommended insects as a viable solution to food insecurity, even in relatively wealthy countries. Now, the whole idea may turn the stomach of many, but the report was welcome news to the small US community of insect eating advocates, or entomophagists. One of them is Dave Gracer, who's been running an edible bug business called Small Stock Foods since 2009. Living on Earth's intrepid reporter Emmett FitzGerald joined him on a bug hunt in Rhode Island.

FITZGERALD: Dave Gracer has eaten all kinds of bugs.

GRACER: I’ve had about 60 or so species of arthropods, mostly insects, but I’ve had scorpions, a giant centipede, and isopods, which are those rolypolies which are quite good.

Dave going for a stinkbug in an autumn olive (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: He’s not a gross-out fanatic, or a former Fear Factor winner, just a guy who thinks that eating insects makes a lot of sense.

GRACER: I do not believe that there is a food production paradigm that can produce nearly as much food so efficiently as insects.

FITZGERALD: Gracer is an edible insect advocate, and the owner of a business called Small Stock Foods in Providence, Rhode Island. He collects edible bugs and sells them to brave eaters around the country. Much of Dave’s stock comes from Asian, African, and Central American markets in Providence and Boston. But today, he’s going hunting in the park.

.jpg)

A jar full of stinkbugs and flowers (photo: Emmett FitzGearld)

[PARKING LOT ATMOSPHERE]

GRACER: So we are in Johnston, Rhode Island, this is Snake Den State Park. What I get from here are several species of grasshopper, a couple of katydids, dragonflies.

FITZGERALD: Which he catches with a butterfly net and a couple of Mason jars. Dave and I set out into the meadow. As we walk, he tells me he eats insects because he believes that our current food system is unsustainable.

[HELICOPTER IN SKY]

GRACER: From my point of view, the way that humans feed themselves now, basically, represents a big middle finger to the natural world.

.jpg)

Dave stalking a dragonfly (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: As the global population continues to rise, he says, food security will only become more of a problem.

GRACER: Look at the future, look at what’s coming our way, it’s really kind of terrifying, 9 billion plus people by 2050, which is really not that far away, and none of the experts have explained where all that food is going to come from.

FITZGERALD: Dave thinks that at least some of that food should come from large-scale insect farming. Many cultures have long traditions of eating insects, which are high in protein, vitamins, and amino acids. Several countries, including the Netherlands and Thailand, already grow insects on a commercial scale.

GRACER: There’s something like 20,000 cricket farms for human consumption in Thailand.

FITZGERALD: Dave says that if he had the money, he would invest in insect farming here in the States. But for now he’s content to volunteer his time.

.jpg)

Success! (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

GRACER: I mean, I’m an adjunct at a community college, how wealthy am I? If I could plug 20 million dollars into this I would, but instead all I can do is 20 million hours.

FITZGERALD: We follow a mowed path, skirting the edge of the field. Redwinged blackbirds balance on the tops of milkweed, and bumblebees flit among the blossoms of an autumn olive.

[BEES BUZZING]

FITZGERALD: We poke our heads into the branches and Dave spots a snack.

GRACER: Ah ha. There's one.

FITZGERALD: I don’t see it. Oh yup, now I do.

FITZGERALD: It’s a stinkbug, Dave says, but don’t be fooled by the name. They smell like soap and taste like cilantro.

.jpg)

Dave’s freezer is packed with bizarre insects, like these waterbugs from Thailand (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

.jpg)

Dave prepares some bugs for Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald to eat (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

GRACER: Stinkbugs are eaten in many parts of the world, they’re called humiles in Mexico and in fact there’s a particular city in which they have a stinkbug festival and there’s a day of the stinkbug.

FITZGERALD: Dave pulls out his jar and leans in.

GRACER: What I’m going to do is do the jar below and the lid above.

[LID SCREWS ONTO JAR]

FITZGERALD: He caps the jar and we walk on. Dave will put the bugs we catch into his freezer where they’ll die within about an hour. They may be small and alien looking, but Dave says he sometimes feels bad about killing insects.

GRACER: They’re animals you know, they would prefer to avoid dismemberment or death just like you and me.

FITZGERALD: But in the end he thinks that killing a few bugs is a more natural way to get food then slaughterhouses or industrial farms.

GRACER: I am reacting to these insects the way any other predator would. It’s an honest exchange of energies like you know what, if I can get you, I will.

FITZGERALD: Dave catches a few more stinkbugs and nabs a grasshopper with his bare hands. As we reach the end of the field, he spots a bright purple dragonfly, perched on a rock.

GRACER: Alright. I’ll go for that.

FITZGERALD: He pulls out his net and begins to stalk his prey.

[RUSTLING]

FITZGERALD: You got him?

GRACER: I got him.

FITZGERALD: So you kind of swiped above it

GRACER: I anticipated where he was going to be.

FITZGERALD: Dave slips the dragonfly into a plastic baggie with the rest of our haul. As we walk back to the car, he reflects on a good day of hunting.

GRACER: So this was some good stuff.

FITZGERALD: Yeah, not bad.

GRACER: We have three types of insects that offer us three types of taste experiences, and in terms of overall numbers we have...

FITZGERALD: Eight stink bugs...

GRACER: ...plus two grasshoppers plus one dragonfly.

[CRICKETS CHIRPING]

FITZGERALD: We drive back to Providence and the headquarters of Small Stock Foods, Dave’s house. He takes me down to the basement where he keeps his stores.

[DOOR CLOSES AND STEPS DOWN TO BASEMENT]

FITZGERALD: Dave opens the door to his freezer. It’s filled with plastic bags and milk jugs, each bursting with legs and wings and antennae.

GRACER: Here these are giant waterbugs from Thailand, they’re called mingda. Here I have part of a large order of grasshoppers from Texas. Oh, here’s the scorpions right here.

FITZGERALD: Small Stock Foods is no big business. Dave only fills about ten orders a year. Most of his bugs go to avant-garde restaurants, novelty party planners, and other clients looking for a little shock value.

GRACER: Dos Equis had a sales campaign, a promo; “the most interesting tacos in the world” to go with the most interesting man, and so they had gourmet taco trucks in a couple of different cities that wanted to do the most interesting tacos and they wanted the most scorpion tacos.

FITZGERALD: But, Dave says, recently, some people in the United States have begun to think of insects as a serious food for the future.

GRACER: There are companies now working to produce industrial commercial supplies of insects for human consumption in the U.S. and that is as of the last 18 months.

FITZGERALD: Farmed bugs could be eaten as proteinous snacks or ground into flour for baking. Dave thinks that someday insects will be space food.

GRACER: Recently Steven Hawking said we need to explore space because the Earth cannot support our species. We’re not going to have cows on Mars. We’re not going to have cows on the space station.

FITZGERALD: But the future of insect consumption depends on our willingness to eat them. Most people crinkle their nose at the sight of a cockroach, but Dave says the hardest bug to eat is your first. He takes me up to the kitchen and lays out a handful of crickets and katydids on a sheet of tin foil.

[TIN FOIL RIPS]

FITZGERALD: I squirm a bit in anticipation as he puts them into the toaster oven

[TIMER DING GOES OFF]

FITZGERALD: So this is a house cricket. Alright, here I go.

[CHEWING SOUNDS]

FITZGERALD: It’s kind of like shrimp!

But the legs get stuck between my teeth and I need some water. A Katydid from Uganda is coming up next.

Oh yeah. Really good. That one’s delicious, its fatty, really greasy really fatty.

GRACER: It’s like a cross between a crouton and bacon.

FITZGERALD: Dave says he likes to snack on Katydids with an afternoon beer, but for me, I’m not sure they could ever replace tortilla chips or popcorn. Dave says that’s not the point.

GRACER: I’ve never claimed that insects taste better than other foods. I prefer sushi, and duck, and pastrami, and lasagna, and ice cream and cheese, and so many other things.

FITZGERALD: But in time, he says, people can learn to incorporate insects into their diet. After all, they’re really just land shrimp. In his presentations, Dave asks people: if you’re willing to eat arthropods like shrimp, why not a grasshopper?

GRACER: And I go into the amusing revelations about what crab and shrimp and lobster eat which is trash and feces and dead animals, as opposed to what grasshoppers and caterpillars eat which is salad.

FITZGERALD: Before I go, Dave gives me a small bag of bugs to bring home. On the stoop outside my house, I recruit a few reluctant tasters. They think the Katydids are all right.

MAN: Hmm not bad, tastes like it's cooked in butter or something.

WOMAN: Hmm tastes fine, like shrimp fries, like seafood.

FITZGERALD: But they aren’t so sure about the crickets.

MAN: Ugh, that one’s pretty gross. You can feel the organs and ... ugh!

FITZGERALD: Insects may well be the food of the future, but for most of us, they’ll take some getting used to.

For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett FitzGerald.

Related links:

- Visit the SmallStock website to order some bugs

- Watch Dave Gracer’s appearance on the Colbert Report

- Read more about entomophagy

[MUSIC: Don Byron “Charley’s Prelude” from Bug Music (Nonesuch Records 1996)]

Eat-a-Bug Cookbook

The Pear Salad with Chiangbai Ants is a prime an example of how Gordon chooses to feature bugs in his food, rather than hide them (Photo: Chugrad McAndrews).

CURWOOD: And when it comes to edible insects, there is one big challenge: how on earth should one prepare six-legged food to appeal to two-legged diners? Well, that's where David George Gordon comes in. He's the award-winning author of many books about animals, including The Eat-a-Bug Cookbook, which is exactly what it sounds like. He joins us now from Seattle to explain the joys and benefits of entomophagy. Welcome to Living on Earth, Mr. Bug chef.

GORDON: Great to be here, thank you.

CURWOOD: So tell me, when did you first start eating bugs? What’s the story of when you ate your first one?

GORDON: You know, I got interested in the subject probably about the mid or towards the end of the 1990s. I had actually been collecting information for another book I was working on called The Complete Cockroach. And that book had a little bit of everything you could possibly know about cockroaches, including people who eat them. So while I was gathering information on that, I wound up with a really fat file folder called bug food. I actually went to an insect fair in Seattle, and they were serving Chex mix with crickets in it, and was pleasantly surprised; they were quite tasty. So that was my first bug that I actually ate on that long...what’s now turned into a 15-year journey.

Gordon likes to use tempura batter and a deep fryer to make the arthropods in his cookbook more appealing, like the Deep Fried Tarantula Spider (Photo: Chugrad McAndrews).

CURWOOD: But give me the case now for why people should be eating insects? I actually should say we should be talking about arthropods because there are spiders in your cookbook as well.

GORDON: That’s right, and scorpions and centipedes, so I say insects and their kin. You know that there are a number of compelling reasons to eat bugs. First of all, there’s health benefits. They’re very rich in protein. They have lots of vitamins and minerals. They're low in fat. And they have amino acids that you might not get elsewhere from your normal diet.

CURWOOD; Talk to me about why bugs are more efficient converters of protein than say fish, poultry and meat.

GORDON: There's a measure of the value of food that’s called an ECI rating. That stands for the efficiency of conversion of ingested food. So the ECI rating is very poor on things like cattle. You give a cow 16 pounds of grain, you'll get 1 pound of steak eventually. And you also need to give that cow thousands of gallons of water over its life. Insects, on the other hand, have much higher ECI ratings. If you give certain insects, oh I don’t know, two pounds of grain, you'll get a pound of insect protein back. So that's way less wasteful than trying to raise cattle. Some insects don't even need water. Things like mealworms actually get their water molecules from breaking down the carbohydrates they’re eating in granaries. So the whole idea of farming insects locally has become a much more popular idea.

The Pear Salad with Chiangbai Ants is a prime an example of how Gordon chooses to feature bugs in his food, rather than hide them (Photo: Chugrad McAndrews).

CURWOOD: So David, tell me how unusual is it to eat insects?

GORDON: Well, we're kind of the oddballs because we don't eat insects. I've read reports that have said 80 percent of the world's cultures do eat some form of land arthropod. We're talking about places like Mexico, South America, Australia, Africa...just about everywhere but Northern Europe and a lot of the colonies that would include the United States and Canada. In that FAO report, they say there's actually 1.9 billion people who are eating bugs right now.

CURWOOD: You’ve got to admit though, David, that some insects really are...well, they’re gross! I wouldn't want to eat a dung beetle, for example, or some bug that had been exposed to pesticides. I mean, what are some of the hazards associated with eating insects?

Gordon with his wife, Karen Luke Fildes, who illustrated the Eat-A-Bug Cookbook (Photo: David George Gordon).

GORDON: Well, pesticides are definitely a hazard. And you know, I mention in the Eat-A-Bug Cookbook that if we got into hand-picking and eating the pests instead of just spraying them with bug spray, we could actually get two cash crops from the same acre of agricultural land. I would always advise people to eat bugs that have been cooked thoroughly. There are potential parasites and germs that could be passed by eating raw bugs. And the same thing would be true about chicken; you wouldn’t want to eat raw chicken or raw pork for those very same reasons.

The other hazards, I would say, well, probably a primary concern is some people are actually allergic to bugs. Now how would they know that if they hadn't been eating bugs before? They would also be allergic to shellfish, so if you went to Red Lobster or some place like that, at the all-you-can-eat shrimp feed and you felt itchy afterwards, well, you probably would have had the same reaction by eating grasshoppers or mealworms or what have you.

Gordon, who is sometimes known as “The Bug Chef”, performs an insect cooking demonstration (Photo: David George Gordon).

CURWOOD: How did you start presenting the concept of entomophagy to the public?

GORDON: Well, I do cooking demonstrations and I've been all over the place at museums and science centers and schools. I've gotten a pretty good reception for my cooking demos, but I've noticed there are, like, three different kinds of people in the audience. There are some people there who are I’d say, they’re fussy eaters. They say, “no way, I'm just here to observe what you're going to do.” There are other people who are more like the “I'll try anything once” group. Californians are a classic example of that. And then there are a third group. I get the impression that they got up hours earlier and drove a long distance, and they can't get started fast enough. They’re like, “when you gonna serve the bugs?”

Gordon carefully cuts off the venomous scorpion tail before dining, even though cooking a scorpion denatures the proteins that would provoke a reaction (Photo: David George Gordon).

CURWOOD: Now let's see. I'm looking at your cookbook. There’s some recipes here for everything from Bugs in a Rug, Really Hopping John, and Ant in Pants, and Cream of Katydid Soup. And I have to say though that most of these aren't like Cream of Katydid Soup. They’re more quite...they put the insects right in your face. There’s no hiding what's in the ingredients. You’re going to see it. I mean, you have a salad with ants all over it, for example.

GORDON: Yes, it was a conscious decision on my part. I’ve talked to people, though, you know they’re boasting to me; they say, oh, I went to a French restaurant and had escargots - snails - and I say, 'well that's great, what it taste like?' and their answer almost uniformly is 'garlic butter'.

Gordon keeps a tarantula as a pet, but makes a point not to bond with the tarantulas he cooks (Photo: David George Gordon).

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

GORDON: Because they’ve been seasoned. I kind of would like people to be able to say, 'well, they taste kind of like slugs, but a little more piquant!'

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

GORDON: I really wanted people to be aware of what they were eating and what it tasted like, so not only did I not cover up the bugs, I also didn’t want to bury them in elaborate sauces or overseason them.

CURWOOD: So, I’m looking at this photo in your book. It’s got to be one of the best photos here. It’s for Fried Green Tomato Hornworms where these giant, bright green caterpillars rest on top of breaded tomatoes.

GORDON: So, yes, I chose to make sure that the hornworms in that recipe are really prominent. They’re big and green to begin with, so it’s hard to conceal them.

CURWOOD: And they’ll show up in your garden if you have tomatoes out there.

GORDON: You know, if you can’t beat them, you should eat them! That’s my motto.

CURWOOD: Let’s see. Chirpy Chex Party Mix.

GORDON: That’s a delicious one, and that’s sort of my homage to what got me started in the first place. It’s basically a Chex mix that you can make yourself, all sized proportionately with the bugs. And then I like to use oven-baked crickets. These are crickets that I’ve purchased, they’ve been frozen, defrosted and then baked on a cookie sheet. Mix those in with that snack mix and you get quite a satisfying little crunch there.

CURWOOD: Hey, uh, Dave, before you go, what’s your favorite recipe in the book?

GORDON: I really like waxworms. These are animals that in the wild as caterpillars actually feed on the wax and the honeycomb in a beehive. When you actually roast them, they taste like pistachio nuts. It’s, like, what’s not to like? So I have a recipe in this book for White Chocolate and Waxworm Cookies. If I did prepare those and offered them to you in a blindfold test, you’d probably want another one.

CURWOOD: And if I had to look at it?

GORDON: Well, you might have qualms there because, you know, we’ve just been trained to think...be distrustful of anything that’s caterpillar or wormlike in shape.

CURWOOD: So, what, in 50 years, how do you see people getting their protein?

GORDON: I think what you’ll see in labels...I’ve already seen this not necessarily about insects, but they say animal protein. It doesn’t say what those animals are. They could be sea urchins for all I know. But in actuality, I think they’ll start doing that with insects. So I think insects will be reared commercially. I think they will be used as an ingredient in a lot of our foods, as supplements, what have you, to bolster the idea of getting a little bit more protein from your meal. But I also think they will be served as delicacies just like they are in these other countries where bug eating reigns. And people will actually, I hope, become more sophisticated, and learn to get over their fear and hatred of insects, and start enjoying them like the rest of the world does.

CURWOOD: David George Gordon is the Bug Chef and author of The Eat-a-Bug Cookbook. David, thanks so much for taking the time.

GORDON: Thanks for having me. This has been great.

CURWOOD: And if you want to try eating bugs yourself, there are recipes at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Eat-A-Bug Cookbook

- David George Gordon’s website

- Eat-A-Bug Cookbook Recipes

[MUSIC: Carlos Santana “Mandela” from Freedom (Sony Music 1997)]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth, heading out into the darkness, net in hand in search of stealthy night fliers.

MOSKOWITZ: There’s something kinda magical about being out at night with all kinds of biodiversity - everything from the size of a pinhead up to a moth the size of your hand.

CURWOOD: Celebrating National Moth Week and much more next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Poncie Rutsch, Erin Weeks, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of Red Tomato, supplier of rightious fruits and vegetables from Northeast family farms. www.redtomato.org. This is PRI Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth