December 6, 2013

Air Date: December 6, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Worrisome Arctic Ocean Methane Leaks

View the page for this story

New research based in the East Siberian continental shelf of the Arctic Ocean finds the powerful greenhouse gas methane is escaping from the seabed into the atmosphere twice as fast as scientists previously thought, threatening runaway global warming. University of Alaska professor Natalia Shakhova talks with host Steve Curwood about the research. (06:20)

GMO Study Retracted - Censorship or Caution?

View the page for this story

A French study in 2012 led by Gilles-Eric Séralini found animals fed Monsanto’s Roundup Ready corn had increased mortality and more tumors than a control group. Amid heavy industry criticism, the journal that published the research has retracted the study from its archives. Host Steve Curwood talks to Michael Hansen, a senior scientist at Consumer’s Union, who views the retraction as a form of censorship. (07:05)

Sacred Grounds Versus Coal Transport

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

Plans to export coal from the Pacific coast at Cherry Point in Washington State face a new, yet ancient, obstacle. As Ashley Ahearn of the public radio collaborative Earth Fix reports, the proposed terminal would be on Native American sacred grounds. (07:20)

Messed Up Migrations

View the page for this story

From the wildebeest to the monarch butterfly, this year many of the world’s great animal migrations are out of whack. Migration expert and Princeton Ecology professor David Wilcove joins host Steve Curwood to discuss what’s going on. (11:10)

Peak Bagging

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

The Highpointers Club is a group of dedicated and somewhat eccentric outdoor enthusiasts who try to reach the highest point in all 50 states. To achieve their goal, members need to summit giant peaks like Mt. Denali in Alaska. But as Living on Earth's Emmett FitzGerald learned in Rhode Island, even the lowest highpoints can be a challenge. (10:30)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood digs beyond the news headlines with Peter Dykstra publisher of Environmental Health News and the Daily Climate. (05:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Natalia Shakhova, Michael Hansen, David Wilcove

Reporters: Ashley Ahearn, Emmett FitzGerald, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. A provocative animal study that links genetically modified corn to tumors and early death is retracted by the publisher.

HANSEN: It's almost like an act of scientific censorship because when a paper is retracted it disappears; it's as though it's never been published, and it makes me wonder, are we in the Soviet era and people are trying to rewrite history?

CURWOOD: Who brought the pressure and why. Also, coal versus the rights of Native Americans; there are tribal artifacts at the exact site targeted for a huge export terminal.

CAMPBELL: There's a fancy kind of handle. This is an awl made out of an ulna, a deer ulna. They would probably be used in basketry. Human remains have been recovered at the site and it’s highly highly highly unlikely that there are not human remains in unexcavated areas of the site.

CURWOOD: We'll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm. Makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

Worrisome Arctic Ocean Methane Leaks

The continental shelf of the eastern Arctic Ocean runs along the coast of Siberia in the Laptev Sea, East Siberian Sea, and Chukchi Sea, west of Alaska. (Wikipedia Commons)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. We begin this week with some startling news from the far north. There are millions of tons of the powerful greenhouse gas methane trapped underwater in the continental shelf of the Arctic Ocean. This methane had been held in place for thousands of years by a cap of frozen soil on the seabed. But now research at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks has found this methane is escaping into the atmosphere at faster and faster rates, adding to global warming in a feedback loop that accelerates the warming. Joining us by Skype to explain is Natalia Shakhova, lead author on the study. Welcome to Living on Earth.

SHAKHOVA: I'm glad to be with you.

CURWOOD: Now your research area was the East Siberian Arctic Shelf. Can you tell me about that? Why is that an important area for this type of research?

SHAKHOVA: The East Siberian Arctic Shelf is important area because it composes a significant fraction of the Arctic Shelf. It is about 25 percent of the Arctic Continental Shelf, and why it is important is because the seabed of this shelf is very thick - it’s a few kilometers of thickness. And this includes in itself the so-called “super carbon pool.” It is covered with subsea permafrost. Permafrost is a frozen ground which is on top of the sediments and they serve as a cap preventing or capturing the methane escaping from the seabed. And because the permafrost was thought to be stable, and reliably preventing this methane escaping from the seabed deposits, this area has never been considered a source of methane to the atmosphere, never until very recently when started investigating this area ten years ago.

CURWOOD: So what were the previous estimates about methane being released from this area of the Arctic, and how does that compare to what you have found in your research now?

The sea surface above the East Siberian continental shelf of the Arctic Ocean is made up of broken ice and methane bubbling to the surface. (Igor Semiletove, University of Alaska Fairbanks)

SHAKHOVA: During those five years of investigation we accumulated enough knowledge to report about eight million tons of methane escaping annually to the atmosphere of our planet. Now we’re budgeting about 17 teragrams, 17 million tons of methane escaping into the atmosphere of our planet, and this is on par with what Arctic tundra is currently emitting into our atmosphere, and Arctic tundra is thought to be the major source of methane, natural source of methane, in northern hemisphere, so it’s kind of comparable to terrestrial sources and it is even more important I think.

CURWOOD: And why is that?

SHAKHOVA: Important because in other ecosystems, methane, to be released, needs to be produced first, because methanogenesis is the process responsible for the origin of methane. In the sea bed, as I said, this methane has been producing for hundreds of thousands of years, but been prevented from escaping to the atmosphere because the permafrost on top of the sediment has been serving as a cap, as a seal, preventing the escape.

CURWOOD: So if there’s 17 million tons of methane coming from this East Siberian Arctic Shelf, the equivalency for carbon dioxide emissions is what, 20 times as much?

SHAKHOVA: It is at least 20 times as much, from 20 times to 80 times, so if we’re talking the 17 teragrams of methane, and you can do your math, so you’re coming up with much greater numbers in terms of the carbon dioxide equivalent for these emissions.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean really, if it’s like 30 times...we’re talking about a half a billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent.

SHAKHOVA: Right, something about that. The concentration of methane in the atmosphere is increasing much faster than that of carbon dioxide. It means the last 200 years, the concentration of methane in the atmosphere increased about three times. This is much faster that what is carbon dioxide is increasing. This is the major concern of our scientific community.

CURWOOD: So we have triple the amount of methane in the atmosphere today...

SHAKHOVA: Almost that. Umm-hmm.

CURWOOD: And methane doesn’t last very long in the atmosphere. It’s only there for 10, 20 years before it degrades into carbon dioxide.

SHAKHOVA: After 10 years, right.

CURWOOD: I gather one of the biggest concerns with this increase in methane release is that the Arctic has the potential to become a feedback loop. Can you explain that for us?

SHAKHOVA: Absolutely. Absolutely correct, because warming of permafrost leads to its failure to prevent the carbon pool from releasing, and the carbon pool, and in particular the methane, which is ready to go, which has been accumulated for a long time, is what is releasing. And this methane serves as the greenhouse gas, which warms the planet again, which warms the Arctic. So this is the loop, when the Arctic is warming and releases more methane. This methane source to warm the Arctic, and this is how it’s this chain closes.

CURWOOD: So you’re saying the more methane that comes off the Arctic, the warmer things will get, which will lead to more methane coming off the Arctic...

SHAKHOVA: This is exactly how it works.

CURWOOD: This all sounds very scary. I mean, methane’s a very powerful greenhouse gas, and if it’s coming out at this rapid rate, we could be in a lot of trouble.

Prof. Natalia Shakhova leads the Russia-US methane study at the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. (Todd Paris, University of Alaska, Fairbanks.)

SHAKHOVA: Yes, we could be, but we better believe in science and in ourselves because I’m sure that we will be able to come up with ideas how to solve this problem, how to fix it, how to mitigate, how to maybe recover this methane. Because this, the methane, could be used as a fuel. It has some use for humanity, so we better utilize this methane as use for something important for us, rather than just being afraid of things, and there is no use in just being afraid. We need to learn more about this planet. We need to learn more about this planet, we need to learn how to live in agreement in peace with this planet.

CURWOOD: Natalia Shakhova is Professor at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. Thanks so much for taking this time with us today.

SHAKHOVA: Thank you so very much for having me. That’s been my pleasure, and my duty to inform you about the things we are investigating.

Related link:

International Arctic Research Center

[MUSIC STING]

GMO Study Retracted - Censorship or Caution?

Roughly 80% of the corn grown in the US is genetically modified. (Photo: Victor Bayon)

CURWOOD: Roughly 60 percent of corn grown in the US is genetically modified to resist Monsanto's herbicide Roundup. Last year, Gilles-Eric Seralini, a French scientist, found that rats fed a steady diet of Roundup-ready corn had more tumors and died earlier than rats in a control group. Monsanto objected, saying the study did not meet minimum accepted standards for this type of scientific research. Now the Journal Food and Chemical Toxicology, that published the Seralini study, has decided to retract it. For some clarification, we turn now to Michael Hansen, Senior Scientist at Consumer’s Union. Welcome to Living on Earth, Michael.

HANSEN: Glad to be with you.

CURWOOD: So first off, why was this study so controversial? What were the criticisms of the research here?

Séralini’s paper includes these photos of tumors found in rats that ate genetically modified corn and Roundup. (Séralini et al)

HANSEN: The main criticism was that the number of rats that they tested per group, ten rats, was too small for a cancer study, that you should at least be using 50 rats and they said that the strain of rat that was used, Sprague-Dawley rats, are prone to tumors. So those were the two main criticisms, and neither of them are really valid.

CURWOOD: Why do you say neither of those criticisms are valid?

HANSEN: Well, basically what Dr. Séralini did was he did the same feeding study that Monsanto did and published in the same journal eight years prior, and in that study, they used the same number of rats, and the same strain of rats, and came to a conclusion there was no problem. So all of a sudden, eight years later, when somebody does that same experiment, only runs it for two years rather than just 90 days, and their data suggests there are problems, that all of a sudden the number of rats is too small? Well, if it’s too small to show that there’s a problem, wouldn’t it be too small to show there’s no problem? They already said there should be a larger study, and it turns out the European Commission is spending 3 million Euros to actually do that Séralini study again, run it for two years, use 50 or more rats and look at the carcinogenicity. So they’re actually going to do the full-blown cancer study, which suggests that Séralini’s work was important, because you wouldn’t follow it up with a 3 million Euro study if it was a completely worthless study.

(Photo: Kay Ledbetter)

CURWOOD: So now the Journal Food and Chemical Toxicology has put out a statement saying, “no definitive conclusions can be reached with this small sample size.” That’s at least part of the reason for removing the study. How do you respond to that?

HANSEN: Well, if that’s their criteria, many articles that are in the scientific literature find somewhat equivocal results. You wouldn’t say that the paper should be retracted because some data was inconclusive.

CURWOOD: So, Mike, what would be the appropriate circumstances for retracting a scientific study from a journal like this?

HANSEN: The appropriate reasons for retracting a journal article, those have been agreed upon by...there’s this committee on publication ethics, and it should be pointed out that Food and Chemical Toxicology is a member of that organization. When you look at their guidelines, they say there’s only three reasons to retract a paper. One, clear evidence that the findings are unreliable due to misconduct, that is, data fabrication or honest error. Two, plagiarism or redundant publication. Three, unethical research. In the letter that the editor of Food and Chemical Toxicology, Dr. Wallace Hayes sent to Dr. Séralini, they admitted that they found no problem with plagiarism, unethical research or data fabrication. There was no problem there. They just said they were going to withdraw it because there was some data that was “inconclusive,” particularly the number of animals used and the strain of rat used.

CURWOOD: So, you’ve been in the science business for a good while. Why do you think they retracted this article?

HANSEN: Well, there has been a campaign to try to get them to retract this article ever since it came out. Folks in the industry, and very pro-biotech scientists...they’ve attacked this paper, there’s been a campaign of vilification, this almost appears as some kind of retaliation against papers that try to find problems with genetically-engineered foods. It should be pointed out that since this controversy started last year with the publication of this paper, the Journal Food and Chemical Toxicology brought on an assistant editor to deal with the biotechnology, and it’s a scientist, Dr. Goodman, who used to work in regulatory sciences for Monsanto and they’ve actually retracted another paper by Brazilian researchers that looked at the potential adverse health impact of engineered bacteria, and so this is now the second paper that has to do with genetic engineering that this journal is retracting, and it raises issues of why they would do this. And it appears what they’re trying to do, it’s almost like an act of scientific censorship because when a paper is retracted, it disappears, it’s as though it’s never been published. And it makes me wonder, are we in the Soviet era, and people are trying to rewrite history?

CURWOOD: Now as I understand it, the Séralini work is one of among only very few studies that have been conducted by independent scientists as opposed to industry scientists when it comes to the question of Roundup. How correct is that?

HANSEN: Well, that is actually fairly correct. There was an article published in 2011 in the Journal of Food Policy that was actually very interesting because it looked at this issue of conflict of interest, both financial conflict and professional conflict of interest. And for articles in which there was a professional conflict of interest, there were 41 studies, and that means one or more of the authors in each of the studies worked in the industry. Of those 41 studies, every single one of them found no problem. For studies where there was not a professional conflict, that is where none of the authors came from industry, there were 51 studies, 12 of them found problems. That was a highly statistically significant difference, the probability of that happening by chance was less than one in 1000, was less than .001. So what that suggests is that if a study on GMOs involves an industry scientist, if they’re an author on it, it will invariably find no problem at all with the GMO.

CURWOOD: So at the end of the day, Mike, what is the scientific consensus about the safety of people who eat food treated with roundup?

HANSEN: There is no scientific consensus on the health impacts of eating foods treated with Roundup. However, there is data that does link Roundup levels to non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, and there’s evidence that there might be birth defects. Those are the two issues that have been related to Roundup and that need to be looked at further.

CURWOOD: Mike Hansen, Senior Scientist at Consumer’s Union. Thanks so much, Mike, for taking the time.

HANSEN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Monsanto comments on the Séralini study

- Original Séralini study published in 2012

- Listen to the original LOE story on the Séralini story

- Read the Journal Food and Chemical Toxicology statement about the retraction

[MUSIC: Chico Hamilton “Strut (Joey Davis Redux)” from Believe (Joyous Shout Records 2006)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...trouble for some of the iconic great migrations. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Frank Zappa: Peaches En Regalia” from Hot Rats (Zappa Records 2012 Reissue) Frank Zappa (12/21/1940 – 12/4/1993) The Tenth Anniversary of Frank’s passing]

Sacred Grounds Versus Coal Transport

(Kate Campbell)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. The largest coal export terminal in North America could well be built in Northwest Washington State at Cherry Point. Native Americans, including the Lummi Nation, have lived around Cherry Point for millennia. Now the Lummi are speaking out about what they stand to lose if the site is developed. Ashley Ahearn of the public radio collaborative EarthFix has the story.

AHEARN: Jay Julius pulls up his hoodie and guns the engine of his fishing boat. We're leaving the Lummi reservation north of Bellingham, Washington. Julius is a councilmember of the Lummi Tribe.

JULIUS: So now we're moving out to the deep.

AHEARN: Cherry Point stretches out before us - a long strip of green coast - boxed in on one side by an oil refinery and on the other by an aluminum smelter.

JULIUS: The current tankers come through here, through this little channel to get to the refineries up there and that's where the coal tankers would come through.

AHEARN: We approach Cherry Point and Julius cuts the engine. His voice grows soft as he looks towards the shore.

JULIUS: I see this as my people’s home. I can envision it. I know what’s there now. Our people used to use this as a harbor.

AHEARN: The Lummi and their ancestors have inhabited Cherry Point for more than 3,000 years. They signed away this land in a treaty with the federal government in 1855, but they still have strong cultural and spiritual ties to this place. In the 1950s white people began excavating Lummi cultural artifacts at Cherry Point from a site known as 45WH1.

[DOOR OPENING]

Its exact location is not publicly shared, but it's the most heavily studied archaeological site in Whatcom County.

CAMPBELL: The Cherry Point collection's big. We have at least 150 boxes.

AHEARN: Sarah Campbell has been analyzing artifacts from Cherry Point and site 45WH1 since the late ‘80s. She's a professor in the anthropology department of Western Washington University in Bellingham. Campbell takes me into a small room lined with metal shelves. She squats and points at several rocks on a bottom shelf.

CAMPBELL: I'm not really sure I'm up to pulling it out but if you look back. Can you see this one?

AHEARN on tape: Oh wow.

CAMPBELL: There's the hole right there. That’s a really big one.

AHEARN: Thousands of years ago, someone bored a hole through the top of the rock so it could be used to weight down fishing nets. Campbell pulls out other boxes and sifts through dozens of tiny plastic bags, each one containing artifacts from site 45WH1. Harpoon points, beads, jewelry…

CAMPBELL: There's a fancy kind of handle. This is an awl made out of an ulna, a deer ulna. They would probably be used in basketry.

AHEARN on tape: Are there human remains at this site?

CAMPBELL: Yes there are human remains. Human remains have been recovered at the site and it’s highly highly highly unlikely that there are not human remains in unexcavated areas of the site.

AHEARN: The Gateway Pacific Terminal could be built on top of this site, despite the risk of disturbing ancient Native American remains.

BROOKS: The state law says they must be protected, but it doesn't say they can't be moved.

Jay Julius is a Lummi tribal council member and fisherman. (Ashley Ahearn)

AHEARN: Allyson Brooks is the head of the Department of Archaeological and Historical Preservation. The state agency reviews potential impacts to historic sites when developments, like the Gateway Pacific Terminal - are proposed. Brooks says that under the National Historical Preservation Act, certain measures have to be put in place before construction can begin at a place like 45WH1, or WH1 as she calls it.

BROOKS: So in this case if WH1 is going to be impacted in any way, if there's any ground disturbance, or even if roads are going to be put over the top with fill, the process is avoid, minimize and mitigate.

AHEARN: That means the companies that want to build the terminal need to have a plan in place before construction can begin, and they need to consult with the Lummi about the potential impacts to the archaeological site. But what few people know is that SSA Marine and Pacific International Terminals, the companies that want to build at Cherry Point, have already disturbed the site.

In 2011, Pacific International Terminals bulldozed more than nine miles of roads at Cherry Point and cleared more than nine acres, including some wetlands. The company was sued for violations of the Clean Water Act and ended up settling with ReSources, a Bellingham-based environmental group. Very few details of the settlement were made public, until now.

[PAPERS RUSTLING, LOWNEY TALKING]

AHEARN: At his law offices in Seattle, Knoll Lowney rustles through files from the case his firm won. He pulls out a map that he got from Pacific International Terminals through the lawsuit. It's dotted with little green squares. These mark 37 boreholes the company drilled at Cherry Point. One of those boreholes was right in the middle of archaeological site 45WH1.

LOWNEY: This is the one that's in the middle, that's right in the middle of it.

AHEARN: Companies drill boreholes to test the soil composition and geology of a site‚ basically to see if a site like Cherry Point will stand up to 48 million tons of coal moving over it each year. No one knew about the disturbance at Cherry Point until a local was out walking in the area, saw the activity, and reported it.

The company said it was an accident. Lowney disagrees. He pulls out another document from Pacific International Terminals. It was submitted to the Army Corps of Engineers four months before they began non-permitted drilling at Cherry Point. It shows that the company knew the exact location of site 45WH1. It also knew that it would need permits and consultation before it could do any work near the site. But it drilled there anyway.

LOWNEY: By going ahead and doing it illegally and then saying, “oh sorry” but actually having the data now, it allows them to start planning now so that if they get their permits someday, they're ready to build.

AHEARN: Pacific International Terminals settled with Lowney's clients for $1.6 million dollars. The Lummi chose not to take part in the lawsuit. The tribe was offered $94,500 as mitigation for the damage done. They refused the money. Pacific International Terminals and their parent corporation, SSA Marine, declined repeated requests to be interviewed for this story. But Bob Watters, the Senior Vice President of SSA Marine, emailed a statement.

It reads:

"We sincerely respect the Lummi way of life and their cultural values. Claims that our project will disturb sacred burial sites are absolutely incorrect and fabricated by project opponents. We continue to believe we can come to an understanding with the Lummi Nation regarding the Gateway Pacific Terminal.”

At his offices at Lummi Tribal headquarters, council member Jay Julius shakes his head.

JULIUS: No is no. If they don't understand that we are at a no then…

AHEARN: His shoulders tense with quiet rage when I ask him about what Pacific International Terminals did at Cherry Point.

JULIUS: Every time I go up there it's all that's on my mind is what took place here at Cherry Point when these guys bulldozed over it and called it an accident. It's obvious. It doesn't take a genius to figure it out.

AHEARN: The Army Corps of Engineers will ultimately decide how to weigh the cultural and spiritual impacts the Gateway Pacific Terminal will have on the Lummi people. If the tribes aren't happy with the Corps' decision, they could sue.

I'm Ashley Ahearn in Bellingham.

CURWOOD: Ashley Ahearn reports for the public radio collaborative, EarthFix. There's more at our website LOE.org.

Related link:

Earth Fix

[MUSIC: “Bill Frisell A Beautiful View” from Big Sur (Emarcy jazz 2013)]

Messed Up Migrations

Monarch butterflies in Mexico (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Some of the most awe-inspiring spectacles of the natural world are the migrations of creatures great and small - from turtles and terns, to butterflies and beasts. But this year some of the world’s most famous migrations seem to be out of sorts. To find out what’s going on, we called up David Wilcove, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Princeton. Welcome to Living on Earth.

WILCOVE: It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: First, let’s talk about the butterflies. As I understand it, usually by November there are millions of Monarch butterflies that have arrived in Central Mexico. Could you describe that migration for us?

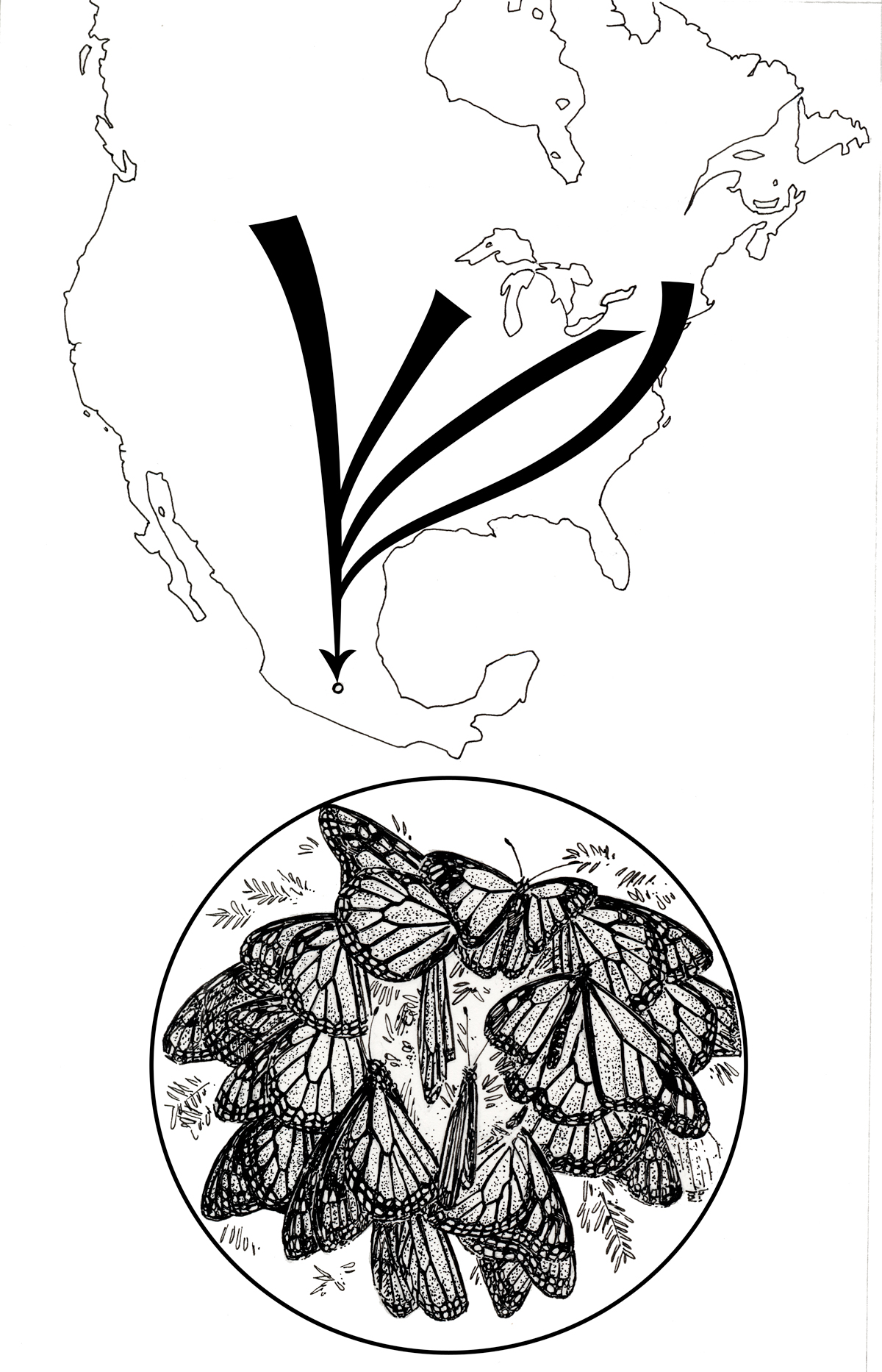

Monarch butterflies migrate for the northern United States down to Mexico where they roost in bunches in pine forests in the state of Michoacán (Illustration: Louise Zemaitis)

WILCOVE: It’s really an extraordinary migration. The butterflies begin moving south from the northeastern United States around August or September, and they funnel into this tiny area in Mexico where they will roost for the winter, and then in the spring, the survivors will head north, and they will hit the Gulf States, lay eggs and die. Those eggs will develop into the next generation of Monarchs, which will continue migrating north, they’ll lay eggs and die. And it takes about three or four generations until Monarchs have repopulated the eastern United States and Canada. And that last generation born in the summer is the one that will somehow know to go back to that small area in Mexico where their great-grandparents left the previous spring.

CURWOOD: When exactly are the monarchs supposed to arrive and what’s the cultural significance to folks in Mexico?

WILCOVE: Well, the monarchs arrive as we get into the late autumn beginning of the winter, and for some people in Mexico, it’s really part of the Day of the Dead celebrations, the idea being that the monarchs represent the souls of their departed loved ones returning to Mexico, returning to that set of forests in the mountains. The Monarch migration is also an important tourist draw. It’s such a beautiful phenomenon to see these millions of butterflies covering the trees that people from around the world come to Michoacan, Mexico, to see it. And so it’s become an important economic force in those communities, and of course, in a broader sense, it’s part of the world’s natural heritage because it is such a remarkable phenomenon.

CURWOOD: But this year, things were different. What happened?

WILCOVE: It appears as through the Monarchs are either very late in arriving at the site, or very few of them have survived making it down to Mexico. So we hope that it’s merely a case of them being very late, and that eventually we’ll get a healthy population, but there is the alarming possibility that the population has really crashed.

CURWOOD: What could put them at risk?

WILCOVE: The Monarchs face a number of problems. The one that’s gotten the most attention over the years has been illegal logging of the forests on that mountain in Mexico where they winter. So if you imagine the trees as providing a kind of thermal blanket for the butterflies, the illegal logging essentially means that we’re cutting holes in the blanket, and so when the cold weather hits, many of the Monarchs freeze to death. But there’s another issue that is starting to attract attention, and that’s the loss of the milkweed flowers that the butterflies lay their eggs on and rely on for their development. And it turns out that more and more farmers are planting crops that have been genetically modified so that they can withstand herbicides, and the farmers then apply herbicides to eliminate plants like the milkweed, which they view as a competitor with the crops. So unfortunately, as we’ve gotten cleaner, more industrialized, agricultural fields, we’re losing habitat for Monarchs and all sorts of other insects.

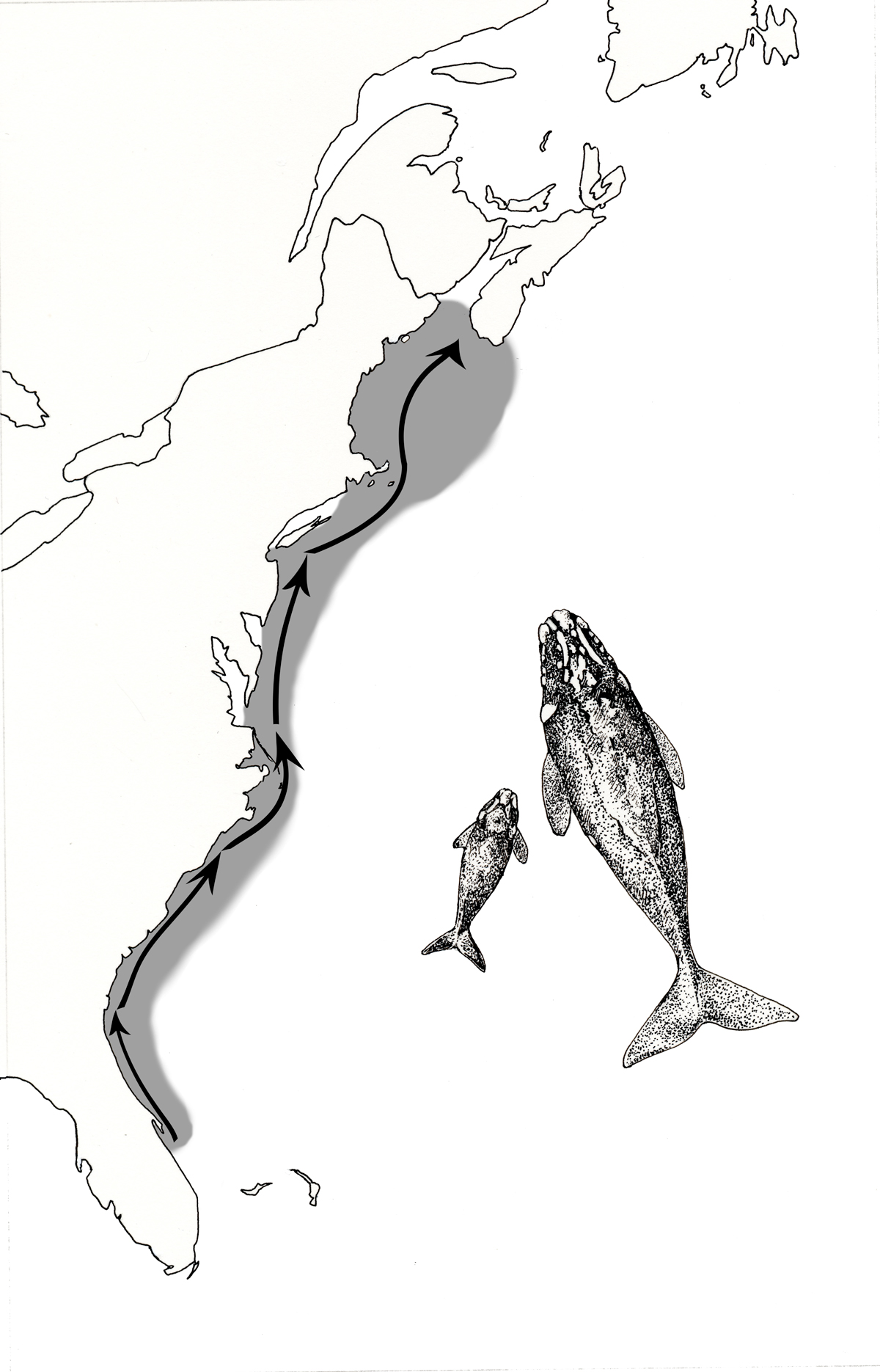

CURWOOD: Now, similarly Right whales off the New England coast aren’t showing up at their usual breeding grounds.

Northern Right whales are some of the most endangered mammals in North America (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

WILCOVE: That’s right. The Northern Right Whale’s a really interesting animal. It’s probably the rarest mammal in the United States. They’re only a few hundred of them left, and historically, a large percentage of the population has spent the summer in and near the Bay of Fundy where they feed on the abundant zooplankton there. However, this summer relatively few showed up. Now the folks who study the Right whales don’t believe that those animals that are missing have died. They think they’ve moved to another place for the summer, and they don’t know where they are. So it’s a concern because if you don’t know where they are, it’s much harder to protect them.

CURWOOD: What do scientists think is going on?

WILCOVE: They’re not certain. They know that these zooplankton, these little copepods that the whales depend on have shifted in abundance, and they think that that may be causing the whales to find new foraging areas for the summer. Why that is all happening is still a subject of research, but there’s a strong possibility that we’re seeing climate change here, changing the ecology of the Bay of Fundy, changing the food resources that the whales depend on, and causing the whales to move elsewhere.

Northern Right Whales migrate from Florida to the Bay of Fundy, but this year the Right Whales haven’t showed up in Canada (illustration: Louise Zemaitis)

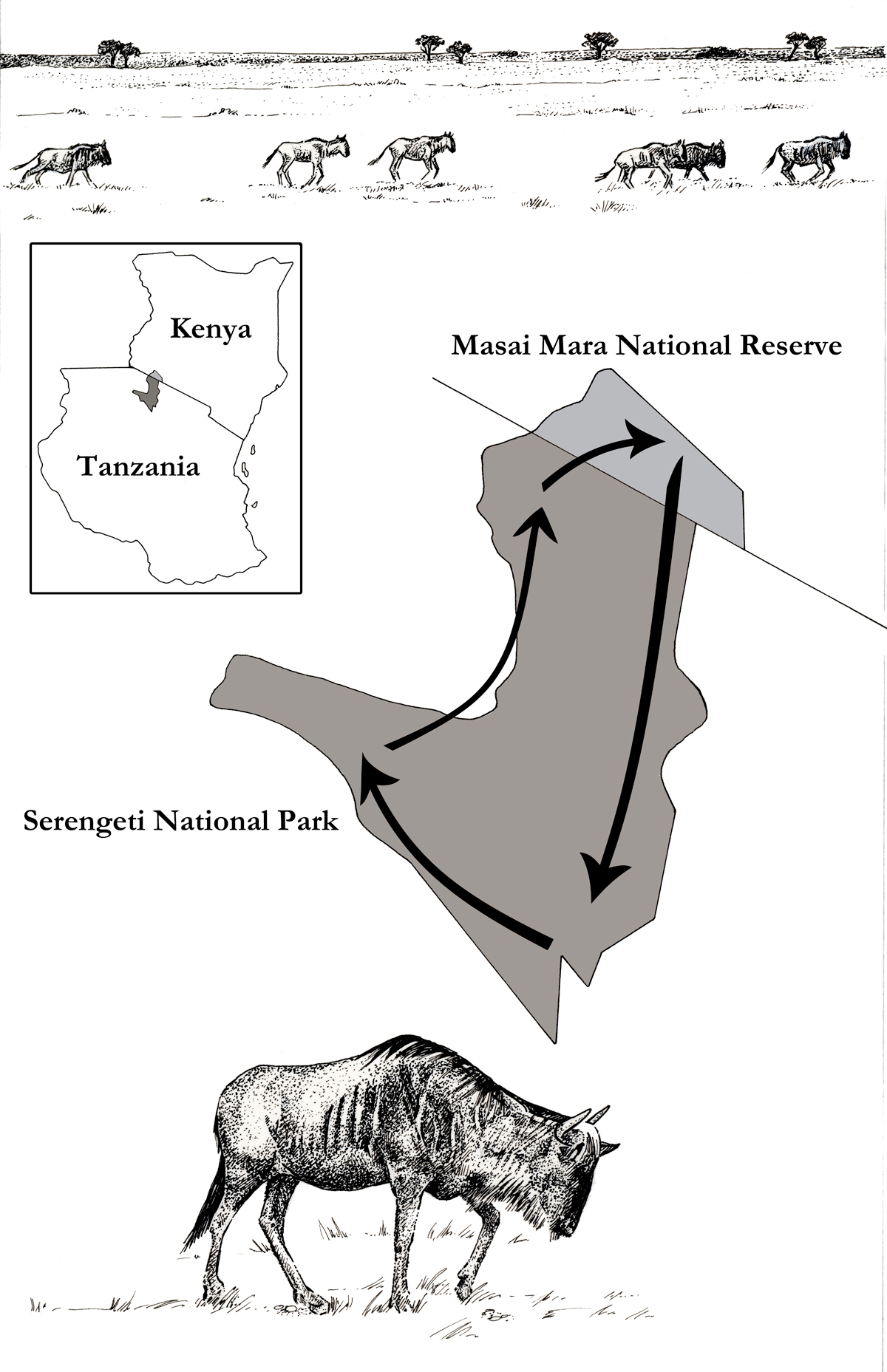

CURWOOD: Now of course one of the largest migrations in the world, and certainly spectacular is that of the Wildebeest in east Africa. Could you describe that for us?

WILCOVE: It really is a remarkable sight. I’ve had the great pleasure of watching animals in many parts of the world, and I think the Wildebeest migration in the Serengeti is just about the most spectacular thing I’ve ever seen. It’s over a million Wildebeests that move between Kenya and Tanzania in vast herds. They move to new places in response to the seasonal rains. So when the rains come to Tanzania and turn the Serengeti plains into this lush grazing area, the Wildebeests move down from Kenya to that spot, and then when they’ve depleted the grass, the rains are through so there isn’t a lot of forage to eat, they head back north. And what’s happened this year is that the Wildebeests seemed to have left Tanzania early to go back to Kenya because there wasn’t much forage for them in Tanzania due to a drought.

CURWOOD: How is this impacting tourism there in Kenya?

WILCOVE: Well, it’s probably beneficial to the Kenyans in the sense that tourists that want to see the Wildebeests at this time of year are going to go to Kenya instead of Tanzania. But it’s bad news for the Tanzanians because they won’t get the visitors that they would otherwise get. More importantly though it’s potentially bad news for the Wildebeests because this is an animal migration that is geared towards following the rains, capturing the grass that comes about as a result of those rains. If, as a result of climate change, rainfall patterns change it could pose real problems for the health of the Wildebeest population, or it could change the route of the migration and conceivably cause the animals to move out of the protected areas into places where they would not be protected.

CURWOOD: What impact would that have on the ecosystem as a whole?

.jpg) The wildebeest migration in East Africa is one of the world’s largest migrations (photo: Harvey Barrison)

The wildebeest migration in East Africa is one of the world’s largest migrations (photo: Harvey Barrison)

WILCOVE: The Wildebeests are very important to that ecosystem. They are basically recycling nutrients because they’re consuming the forage, and then through their dung they redistribute nutrients. So it could have a major disruptive effect for many of the grazing mammals, any of the birds that occur in these savannahs.

CURWOOD: Generally, why do you think we’re seeing so many disruptions in the animal migration patterns?

WILCOVE: We’re seeing disruptions in the animal migration in large part because we’re disrupting the environment. You have to remember that migratory animals really connect different parts of the world, and so they’re sensitive to changes in any of those parts. When due to things like climate change or habitat alteration we change their summering grounds, wintering grounds or even the stopover sites...they’re going to respond. In some cases, their numbers are going to decline, or crash completely; in other cases, they’re going to have to find new places to go to. Either way, there are useful early warning signs of the types of disruptions that we’re creating in the environment.

This year, the wildebeest headed back to the Masai Mara early, because of drought in the Serengeti Park in Tanzania (illustration: Louise Zemaitis)

CURWOOD: So far, climate change amounts to less than two degrees centigrade, about a degree centigrade around the world. How do you think climate change going forward would impact migration?

WILCOVE: It’s not just changes in temperature. It’s changes in precipitation, which can be very important for animals because those precipitation changes affect vegetation. It’s also changes in the extremes of heat, cold, drought, flood, all of that can be very disruptive to animal populations. We’re really basically reshuffling the deck and the consequences are going to be idiosyncratic and difficult to predict.

CURWOOD: What can we do to prepare for these changes and better protect migratory species?

WILCOVE: The best thing we can do, in my opinion, is to continue to protect natural ecosystems, to maintain connectivity between protected areas, so animals, plants, food; to restore connectivity where we’ve disrupted it, and of course take steps to reduce climate cange.

David Wilcove in a forest in Bhutan (photo: Paul Elsen)

CURWOOD: David Wilcove is a Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton University and author of the book No Way Home, about migration. Thanks, David, for taking the time with us today.

WILCOVE: It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Check out David Wilcove’s book on animal migration No Way Home: Decline of the World’s Great Animal Migrations

- David Wilcove’s website

[MUSIC: Louis Sclavis Atlas Trio “Migration” from Sources (ECM Records 2012)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...heading for the hills to hit the high points. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jim Hall: “Big Blues” from All Across The City (Concord Records 1989) Happy Birthday Jim Hall (12/04/1930)]

Peak Bagging

The little red house by the trailhead used to be occupied by Ed Bouchard and Henry Richardson. (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Collecting things is an age old hobby. From snow globes to baseball cards to sea shells, just about anything can be a collectible if you put it in a nice glass case. But there are people in America who collect something that is never going to fit in a case, the garage, or an attic - the highest points in the 50 states. Emmett Fitzgerald has the story from Foster, Rhode Island.

FITZGERALD: Ask a group of Rhode Islanders what the highest point in the their state is, and you’ll get a few different responses. I’ve heard everything from the fifteenth floor of the Science Library at Brown University to the very top of the landfill in Johnston. Truth is, it’s just an ordinary hill in the woods.

BURK: Right now we’re at the trailhead if you wanna call it that, near the summit of the Rhode Island state highpoint, it’s Jerimoth Hill.

FITZGERALD: Since 1992, Stony Burk has crisscrossed the country in dogged pursuit of an unusual goal—to stand on the highest point of every state in the country. Stony climbs each peak on foot, but getting to the trail requires a lot of driving. Today, he’s standing next to a red jeep he calls Cynthia Rose—the car that’s been with him the whole way.

BURK: She’s been to all 48 state highpoints at least twice. She’s on her third time around. And it’s got almost 395 thousand miles on it. Same motor.

The Jerimoth Hill sign next to Stony Burk’s Red Jeep “Cynthia Rose” (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Stony isn’t the only one with this vacation-consuming hobby. There’s a whole club of people delighted to drive a few thousand miles to stand on top of Clingman’s Dome, the highest point in Tennessee, or Mount Magazine, Arkansas’ apex.

WALLEN: My name is Roy Wallen and I’ve been in the Highpointers Club for…a long time. 15, 20 years probably.

FITZGERALD: The club itself goes back longer then that. Stony Burke says it began 30 years ago, with a guy named Jack Longacre.

LONGACRE: Back in 1987, 1988 he posted an ad in Outside Magazine to see if anybody else who was as crazy as he was to go to the 50 state highpoints and he got a lot of responses and the club was formed from then.

FITZGERALD: Since then, the Highpointers Club has taken off.

LONGACRE: We have over 2500 dues paying members.

FITZGERALD: Only a handful of those have reached all 50 state highpoints. A few of the peaks on the list require serious mountaineering experience and a bit of luck. Stony tried to climb Denali in Alaska twice, only to get blown off the mountain both times. Roy Wallen says you have to prepare for each highpoint differently.

WALLEN: Today ’cause it’s raining I brought a rainjacket and that’s it…if you’re going to a big peak you could have full winter gear and crampons and ice ax.

FITZGERALD: You didn’t bring your crampons for Jerimoth Hill?

WALLEN: [LAUGHS] Not today.

FITZGERALD: Although its only 812 feet tall, Jerimoth Hill isn’t the lowest highpoint out there. That title belongs to Florida’s Britton Hill, which clocks in at a mere 345 feet. Still, Stony Burk says the trip to Rhode Island’s highest point isn’t exactly a demanding trek.

A sign along the trail to Jerimoth Hill (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

BURK: The elevation change from the trailhead to the summit is negligible, its probably maybe 8 feet.

FITZGERALD: Although it’s little more than a leisurely walk, Jerimoth Hill wasn’t always so easy to get to. Back in the 1990s, Henry Richardson and Ed Bouchard ran a piano business out of their home by the trailhead. Henry and Ed liked their privacy, and didn’t want hikers wandering around their property looking for the highpoint.

BURK: They would show up in the evening or they would have headlamps on, trying to find it, and they’d wander around in the woods because it wasn’t really clear where the actual summit was. And Henry Richardson could hear these people in his woods and he’d get upset about it and he’d chase these people out, sometimes with a bed post or maybe even waving a pistol or something like that. I’ve heard several stories and I’ve had several friends that had those kinds of encounters.

FITZGERALD: Henry Richardson closed access to Rhode Island’s highpoint altogether, but the highpointers kept coming. Once, a hiker from Iowa tried to take a picture of the no trespassing sign outside Henry and Ed’s little red house.

BURK: Henry ran out of the house and asked him what he was doing and the fella tried to explain it to him but Henry grabbed the camera and ripped the camera strap off his neck and threw it to the ground and broke it. He kind of ran away in fear at that point, and he called the police to see if they could do anything about it, and they pretty much explained that he lived in Iowa and Henry was here and he had the right to keep people off his property.

FITZGERALD: Then two men from Alaska tried to find an alternate route to the highpoint at night. They crossed through another private property a few doors down from Henry and Ed’s house.

BURK: And the fellas that lived there ended up holding the Alaskans at gunpoint until the police came and arrested them.

FITZGERALD: Little Jerimoth Hill soon became notorious in the highpointing community. Rhode Island’s biggest bump stymied climbers with Rocky Mountain credentials. At the height of the Jerimoth Hill drama, the club website declared it ’America’s most inaccessible highpoint.’ Some people even suggested the state circumvent the problem by adding 8 feet to Durfee Hill, Rhode Island’s second highest point.

But the club continued to negotiate for access, and in 1999 they struck a deal with Henry and Ed to allow hikers access to the summit on a few days each summer. Highpointers from all over the country flocked to Rhode Island for a chance to bag Jerimoth.

BURK: On average we’d have between 70 and 180 people on those particular days show up.

FITZGERALD: The open-access days continued without serious incident until 2001, when Henry Richardson died, and a couple named Jeff and Debbie Mosley bought the little red house by the trailhead.

BURK: We made fast friends with the Mosleys over the years. They opened access seven days a week.

FITZGERALD: When the Mosleys moved out, the state bought the land, and now Jerimoth Hill is open to the public all day every day.

[FALLING RAIN]

FITZGERALD: As the rain picks up, we make final preparations for our ascent. Stony suggests we time the trip, and Roy says he’ll count our steps. We huddle under my umbrella, and strike out down the trail.

BURK: 3, 2, 1, here we go…

[MUSIC: Django Reinhardt’s “Django’s Tiger”]

FITZGERALD: OK. We’re 48 seconds in and there’s another Jerimoth Hill sign.

BURK: There’s a little bit of a cross trail here, we’ll take a right.

[FOOTSTEPS]

FITZGERALD: Alright. Getting close.

BURK: Just about 4 minutes in … past another trail sign.

FITZGERALD: Have we arrived?

BURK: We’re here. This is the summit.

FITZGERALD: As we catch our breath, Stony and Roy tally the stats.

BURK: It was right at 300 steps, and our final time, 4:30 minutes. Quite a journey, it was a rugged haul! I’m glad I prepared for it.

FITZGERALD (on tape) How are you guys feeling after that?

BURK: A little out of breath, probably just sit here for a little while and recuperate and see if I can get used to the altitude.

FITZGERALD: Roy says that as highpoints go, Jerimoth Hill isn’t much to look at, just a few rocks in a cluster of trees.

BURK: No there’s no view, but it’s a nice spot in the woods.

FITZGERALD: On top of every highpoint there’s a registry book. Jerimoth Hill’s registry is in green ammo box nestled in the rocks.

[box opening]

The registry book for Jerimoth Hill is inside an old ammunition box (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: The damp pages are filled with names of highpointers from all over the country.

BURK: Pennsylvania, West Virginia, the Woodlands Texas, Gainsville Florida, Dover Massachusetts, Binghamton NY, Silverton Colorado, here’s a note. Can’t believe I put my hiking boots on for this one.

FITZGERALD: Stony scrawls our names into the logbook, then pulls out a pamphlet about the Highpointers Club. It lists some of the records that the club keeps track of - most highpoints in a single day, most highpoints after age 75, that sort of thing.

BURK: Oldest person to reach a highpoint…

Stony Burk and Roy Wallen taking in the view at the summit (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Frampton Ellis. How old?

WALLEN: 91 years 17 days. We’ve had the youngest person to reach a highpoint, Natalie Smith is 11 days old and that was the state of Pennsylvania. Dave Johnson has done all 50 state highpoints in the winter. That is quite an accomplishment. Dogs on highpoints; that one always kind of cracked me up. The Pelligrinis for example, they’ve taken Ozzie up to 36 state highpoints. That’s a cool thing if you can do that. I think dogs have every right to go to highpoints just like people do.

FITZGERALD: Roy Wallen has a record of his own. Once he climbed the six New England state highpoints, Roy started going to the highest point in every county as well.

Emmett FitzGerald and Stony Burk at the top of Jerimoth Hill (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

WALLEN: I’ve done all the New England highpoints, so if I’m going to do any new ones I’m going to have to venture further west.

FITZGERALD: When you start collecting counties as well as states, highpointing can get a bit out of control.

WALLEN: When we go on vacation we go so that I can go do a highpoint, either a state or a county high point.

FITZGERALD: What does your wife think?

WALLEN: She thinks I’m crazy. It’s a disease.

FITZGERALD: It may be a little crazy, but Roy says highpointing provides an organizing principle for adventure.

WALLEN: To me the best part is it takes you places in the country where you’d never have gone otherwise. I probably wouldn’t have gone to Mt. Rushmore if I hadn’t had this driven obsession to go to Harney Peak, which was more important to me.

FITZGERALD: And while not every highpoint would make it into Lonely Planet, each one has something to offer.

WALLEN: They’re all kind of cool, they’re unique. Each one’s got its own flavor and special attraction.

FITZGERALD: Stony Burke closes up the ammo box and tucks it back among the rocks. Wet, cold, but not the least bit tired, we walk back to the car. Stony’s still got two serious peaks left on his list, Mt. Denali in Alaska and Granite Peak in Montana, and he tells me he’s not stopping any time soon.

WALLEN: Anytime I can get out on the road, and go to a highpoint, I’m going for it. I’m standing here in the rain today, I have no problem doing that.

FITZGERALD: As we say goodbye, Stony hands me a yellow Highpointers wristband and tells me I’m eligible to join the club. I’ve already climbed Vermont’s Mt. Mansfield, so only 48 states to go. But I don’t think I’ll be catching Stony any time soon.

For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett FitzGerald at Jerimoth Hill in Rhode Island.

Related link:

Read more about the Highpointers Club on their website

[MUSIC: Daft Punk “Giorgio Moroder” from Random Access Memories (Columbia Records 2013)]

Beyond The Headlines

Lugworm (Wikipedia Creative Commons)

CURWOOD: Time now to check in with Peter Dykstra, publisher of the DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, for a few items from beyond the headlines. He joins us on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve.

CURWOOD: And this week you’re taking us into the land of peer-reviewed journals to find some news, huh.

DYKSTRA: You know, you look at peer-reviewed journals, and sometimes people think they’re wonky and a little remote, but you can find some amazing things in them. One that we found this past week is a story about a rare deadly organism that’s sometimes in powdered infant formula and can be a really serious problem in rare cases for infants and babies. It’s called Cronobacter sakazakii, and scientists at the University of British Columbia found that chemical compounds in garlic can kill the bacteria, and eliminate the risk of infections for infants, possible lethal infections causing meningitis.

CURWOOD: Uh. OK. And what’s that name again, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Cronobacter sakazakii. It’s named after an eminent Japanese microbiologist, Riichi Sakazaki. And if you’re an eminent microbiologist, sometimes there’s no higher honor than to have a potentially deadly pathogen named after you.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

DYKSTRA: The garlic compounds can kill the bacteria and replace chorine and some of the other things that have been used to clean in the manufacturing process for infant formula and it’s hopefully going to save a few lives. And you probably thought garlic was only good for keeping vampires away.

CURWOOD: Peter, I’m not so sure that vampire thing is peer-reviewed though, huh?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, OK. I’m totally busted on that last part about the vampires.

CURWOOD: OK. So tell me what’s up now with the earthworms of the sea.

DYKSTRA: Lugworms. They’re not pretty. They’re not sexy, but they’re one of the most important animals at the base of the ocean food chain. They’ve been ingesting sand - that’s how they stay alive - and from the sand they get nutrients. But lately they’ve also been ingesting microplastics. Those microplastics are increasingly clogging the oceans. They come from our soaps and hand sanitizers. They wash off our manmade fabrics and lots of other places.

CURWOOD: And why are scientists so worried about this?

DYKSTRA: Well, they’ve known about the microplastic problem for a while. They know that microplastics are now one of the biggest waste streams into our waterways. But this is the first time that a peer-reviewed study has seen evidence that microplastics are directly impacting sea life. The lugworms that they studied that ingested microplastics move slower and they eat less, and if it impacts smaller animals at the base of the food chain like lugworms there’s a very good chance it could eventually impact those bigger, prettier, sexier than lugworms, animals that we know from the ocean. And that could be a big problem.

CURWOOD: So what is there to be done?

DYKSTRA: Well, microplastics are too small to be filtered out by our sewage treatment systems, there’s really nothing to stop them from going from our kitchens and laundries and bathrooms to our waterways and then to the sea floor. So maybe that means we have to rethink what we buy, and what we use, and what we consume.

CURWOOD: Peter, this is not good news, but I guess that’s why it’s good to pay attention to those wonky, peer-reviewed journals. I guess the geeks will inherit the Earth someday?

DYKSTRA: And if they do, they’ll know what they’re getting because they’re smart and they’re geeks

CURWOOD: And finally, let’s go back into the history book for a moment, and look at an environmental headline from two decades ago, and what’s happened since.

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s happy 20th birthday for NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement that was signed into law 20 years ago this week by President Clinton. There was a lot of debate back then over whether it was good for the environment, whether it was good for the economy, and you know what? 20 years later we’re still debating whether it’s good for the environment and the economy. U.S. Chamber of Commerce says it been a business bonanza, on the other hand, the AFL-CIO says it’s cost 700,000 lost jobs for Americans.

CURWOOD: And of course there were a lot of environmental concerns about NAFTA when it was launched.

DYKSTRA: Last month NPR reported a story from the Rio Grande Valley, where a lot of those factories are. The water quality along the Rio Grande is still dreadful; it’s always been dreadful, but it’s improved a little bit. There’s an issue with farm exports. NAFTA was a real boon for Mexican farmers, but that’s all come at the expense of using more pesticides and using up more water on Mexican farms. Some of our biggest concerns aren’t in Mexico, they’re with the other treaty partner in NAFTA, that’s Canada, and the province of Quebec last year - this is one example - banned fracking, and as soon as they banned fracking they were immediately hauled into court by an American energy company who claimed that the fracking ban violated the North American Free Trade treaty. So it’s been 20 years, things are still working out, stay tuned.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is the publisher of the DailyClimate.org and EHN.org. Thanks so much, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thanks, Steve.

Related links:

- Check out Daily Climate.org

- Check out Environmental Health News

[MUSIC: Carla Bley “Ida Lupino” from Dinner Music (Watt Works/ECM Records 1977)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Kathryn Rodway, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of Red Tomato, supplier of righteous fruits and vegetables from northeast family farms. www.redtomato.org. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth