May 6, 2016

Air Date: May 6, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

US-EU Trade Deal Controversy

View the page for this story

The EU division of nonprofit Greenpeace released the negotiation text of a partnership between the US and the EU that’s meant to loosen trade barriers. Host Steve Curwood sat down with Jorgo Riss, Greenpeace EU director, for his views on the possible risks for key environmental, labor and consumer protection policies. (08:05)

Huge $$ Advantage from Renewable Energy

View the page for this story

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) reports that doubling the world's renewable energy capacity by 2030 could save the global economy trillions of dollars every year. IRENA's Dolf Gielen tells host Steve Curwood why renewables are already so competitive, and how the world might cash in these savings. (06:40)

Suing to Save the Monarch

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

Two environmental groups have sued the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in an attempt to compel it to formalize Monarch butterfly protection. But expert opinions differ on whether a ‘threatened’ status under the Endangered Species Act will help, or harm, the fragile creatures. The Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant investigates. (04:00)

The Monarch Needs More Than Milkweed

View the page for this story

The past decade has seen steep declines of the Monarch butterfly populations. To save this iconic insect, many people have focused on protecting milkweed, the primary source of food for Monarch caterpillars across North America. Cornell biologist Anurag Agrawal recently studied the various drivers of the species’ decline, and tells host Steve Curwood that to save the Monarch, it will need more than just planting milkweed. (09:45)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra discuss new science teaching standards, adopted by some states and the sticking points that perhaps delay adoption for others, right wing attacks on high profile climate campaigners and perhaps the first ever Pulitzer prize-winning work of environmental journalism. (03:50)

Port Damages Miami Reef

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

The Army Corps of Engineers recently dredged the port of Miami to accommodate larger container ships that will soon pass through a widened Panama Canal. The Corps said the project would have minimal impact on the reef, but new data from NOAA suggests sediment from dredging could have killed many of the corals that provide the city with natural protection from storm surges. Living on Earth's Emmett Fitzgerald has the story. (04:40)

Coral Bleaching in Kiribati

View the page for this story

Abnormally warm waters in the equatorial Pacific are devastating the coral reefs in the Pacific, including Kiribati, triggering a mass coral bleaching event and die-off on these remote islands. UMass Boston coral scientist, Jessica Carilli, and her PhD student, Sean McNally, just back from a recent research expedition in Kiribati, discuss the coral bleaching with host Steve Curwood and suggest how we can prepare coral reefs for the changing climate. (09:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jorgo Riss, Dolf Gielen, Anurag Agrawal, Sean McNally, Jessica Carilli

REPORTERS: Julie Grant, Peter Dykstra, Emmett FitzGerald

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Documents leaked from secret negotiations for the Transatlantic Trade And Investment Partnership, the TTIP, show plans that critics say would hurt labor, consumers and the environment.

RISS: There has been such heavy secrecy that many people have never even heard of the TTIP. A leak will hopefully for the first time make them ask 'what is this, and what does it mean for me?' There's probably a lot more in there that's bad -- probably a lot more ticking bombs that we need to take care of.

CURWOOD: And a warmer, more acidic ocean is helping destroy one of nature’s most vital ecosystems.

CARILLI: Corals are basically trees. They provide habitat, they create islands, they also buffer islands from storms, they're also a potential source of medicines, and they take care of water quality.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies. innovating to make the world a better more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

US-EU Trade Deal Controversy

In 2013, demonstrators wore paper masks of President Barack Obama and Chancellor Angela Merkel in protest of the pending Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, or TTIP, trade deal. (Photo: Jakob Huber/Campact, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Trade deals have been fodder on the US campaign trail this year, with Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders being the most outspoken. And with the recent leak of negotiation documents related to a proposed US-Europe trade deal, there may be even more in future. The environmental organization Greenpeace has released a trove of leaked documents related to what’s called the Transatlantic Trade And Investment Partnership, or TTIP that would loosen trade barriers between the United States and the European Union. Proponents say it could bring in more than $100 billion in revenue for both sides, but Greenpeace EU says the 284-page draft text they released shows it would put global business interests ahead of people and environmental protections. Greenpeace EU director Jorgo Riss joins us from Brussels to explain. Welcome to Living On Earth, Jorgo.

RISS: Hello Steve, I'm happy to be on your show.

CURWOOD: So why did you decide to release all these documents associated with the negotiations for TTIP?

RISS: Well, the TTIP negotiations between the United States and the European Union have now been going on for almost three years in utmost secrecy. In Europe, we had a little bit more information because early on in 2013, civil society and a number of countries here in Europe were saying, “we want to know what's going on, we want to know what you're negotiating,” and the European Commission eventually had to agree to release their demands in the negotiations, some opportunity to discuss them. On the US side, absolute secrecy as far as I know, nothing released to civil society at all.

Greenpeace erected a glass reading room intended for public review of the documents by Brandenburg gate in Berlin following the TTIP leak. (Photo: Gordon Welters/Greenpeace)

CURWOOD: So, tell us, don't reveal your source, of course, but how do you know these documents are legitimate what you have, and what exactly are they?

RISS: Greenpeace was approached by an individual who had access to the documents, who had obtained a full set of documents of what is currently on the table in the negotiations between the USA and the European Union. We first spent a significant among of time retyping all these documents because we had reason to believe that the originals had certain markers that would allow to trace them back to the source. Then, we worked with a network of investigative journalists and after they confirmed our retyped version corresponded to the originals and the originals were indeed authentic negotiating documents, we destroyed the originals so that no one could ever force us to release them and we hope in that way to have protected the source as well as possible.

CURWOOD: What do you think is the most disturbing thing from your perspective that you discovered in these documents?

RISS: It is clear from the documents that the negotiators do have direct contact with some big industry interests, chemical industry and others. We see that the negotiators are moving towards an agreement that would open the door to big industry to have much more their hands on regulation, leave their fingerprints on new laws, on anything from standards on children's toys, levels for residues from pesticides on food, etcetera etcetera. So it really sets up a framework in which future regulation that is meant to protect public health and the environment, could be early on be heavily influenced by industries that have a direct financial interest in these areas.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the precautionary principle and why it's an important factor for you in these negotiations.

Demonstrators protest the TTIP talks that took place in Brussels in February (Photo: Eric De Mildt/Greenpeace)

RISS: Today, in Europe, if you want to produce a chemical and sell it in the EU, you have to provide some basic data to show that it's safe. The European Union, based on the precautionary principal, changed its chemicals regulation system from one where the burden of proof was on public regulators to one where the burden of proof was shifted to the chemicals industry. Before the turn-of-the-century, the European Union had the same type of approach to regulating hazardous chemicals as the United States still has today, and it was up to the public authorities to prove that a chemical was hazardous before they could restrict its use, and that system really didn't work in an environment where the industry was already producing thousands of chemicals, over a hundred thousand different substances were in production the European Union at the time the system changed. For Europeans, getting the precautionary principal into the EU treaty was a big achievement in the 1990s and since then, we've seen the development of some of the most advanced legislation on chemicals in the European Union. And so, in the TTIP leaks, we see that the US negotiators are pushing very heavily that the EU backtracks on this fundamental change of shifting the burden of proof from the public to the private sector.

CURWOOD: Jorgo, how do you respond to claims made by government leaders on both sides of the Atlantic that this deal will spur very much needed economic growth?

RISS: Yeah, that is what they always say. I mean, each time a new trade treaty, a new trade deal is being promoted, we're promised that this will bring growth, that this will bring jobs. I can only say that looking back whether it’s NAFTA in North America or the common market in the European Union, it has always turned out that in reality the benefits where significantly lower, and even now the proponents say that the TTIP in the best possible scenario might lead up to 0.5% of GDP growth. That's not huge, and there are as many economic forecast studies around that go exactly in the opposite direction and they talk about job losses in significant sectors so you have studies going both ways to predict the future but I can say that the promoters of trade always promise a lot.

CURWOOD: What would it take to make a responsible trade deal in your view?

Jorgo Riss is the Director of Greenpeace EU and based in Brussels. (Photo: courtesy of Luisa Colasimone)

RISS: On one hand, you could say we actually don't need such a treaty because trade is going fine between the two biggest economies on the planet. But if you do want, Greenpeace would say the following: we would say first of all, it has to be compatible with the fight against climate change. You can't have a trade deal today where you don't even consider whether increased trade or continuing current levels of trade, whether that is compatible with the achievements of the EU and United States now and the Paris agreement of last year, and secondly, the trade deal should increase standards of living, increase standards of well-being, you know go for something that really improves the lives of people in United States and in Europe rather than go for a deal where you listen closely to what the chemicals industry and some other big businesses are telling you.

CURWOOD: What's your prediction on the effects of this leak will have on further negotiation. Do you have any idea?

RISS: It's very clear that leaks promote public debate, and especially in a case like this where there has been such heavy secrecy that many people have never heard of the TTIP, a leak will hopefully make them for the first time ask, “what is this, and what does it mean for me?.” And I'm sure there's probably a lot more in the back, which goes outside the expertise of Greenpeace. It's not an easy read, but I think for people who work for a better environment, for better society, for labor rights, they should check it and they should see that there are probably a lot more ticking bombs in there that we need to take care of.

CURWOOD: Jorgo Riss is the director of Greenpeace EU. Thanks so much, Jorgo.

RISS: Steve, thank you very much.

CURWOOD: By the way, Cecilia Malmström, EU trade commissioner, says “alarmist headlines” in response to the Greenpeace leaks are a "storm in a teacup." And a spokesperson for the US Trade Representative told Living on Earth, “while the United States does not comment on the validity of alleged leaks, the interpretations being given to these texts appear to be misleading at best and flat out wrong at worst.” There are links to the full comments on our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read the leaked Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership documents

- European Commissioner For Trade Cecilia Malmström responds to the leak

- Official TTIP EU website

- More TTIP info from the Office of the United States Trade Representative

- About the most recent round of TTIP negotiations in New York

[MUSIC: L.A. Guitar Quartet, “4 Variations on Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” Winter Solstice On Ice, Mozart/arr.]

Huge $$ Advantage from Renewable Energy

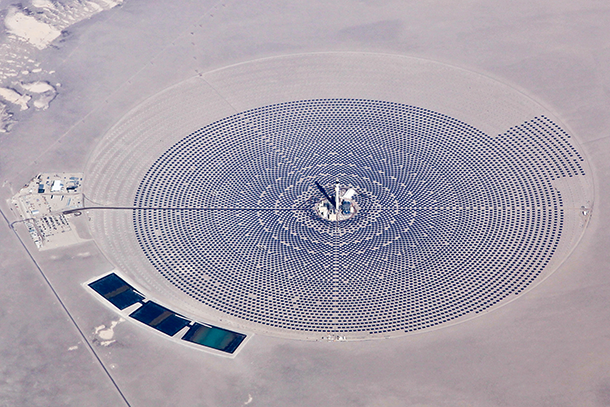

Doubling the world’s renewable energy capacity by 2030 could save $1.2 to $4.2 trillion dollars a year. (Photo: Matt Hintsa, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: When it comes to cost, renewable energy is showing remarkable advantages, compared with fossil fuels. And according to the International Renewable Energy Agency, or IRENA, the cost savings of doubling renewable energy by 2030 could save the world between 1.2 and 4.2 trillion US dollars per year, and that’s on the scale of the entire US federal budget. To find out how renewables could save that much money, we called up Dolf Gielen, he’s Director of IRENA’s Innovation and Technology Center in Bonn, Germany. Dolf, welcome to Living on Earth.

GIELEN: Hi Steve. Pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: $4.2 trillion a year is an enormous number. How did you develop that?

GIELEN: Yeah, we looked at two components. First of all, we looked at the cost of such accelerated renewables deployment and second we looked at the savings. In terms of costs, we looked at the investment needs for renewables and we concluded that these would have to quadruple from around $300 billion US dollars a year today to around $1.3 trillion US dollars a year. But at the same time you would need less investments in the fossil fuels and in nuclear and therefore the additional cost for this accelerated growth would be in the order of $200 billion US dollars a year in 2030, but at the same time there would be significant savings in the sense of reduced local air pollution and therefore reduced health impacts and reduced damages, and second, there would be a significant reduction of global greenhouse gas emissions. And so if you quantify the benefits of these reduced emissions, you find the range of between $1 trillion and more than $4 trillion US dollars per year. So in fact the benefits exceed the costs by a factor of five to 20.

The cost savings from doubling renewable energy production come partly from a reduction in health costs caused by pollution from burning fossil fuels. (Photo: Julia Kilpatrick / Pembina Institute, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: OK, well this is such a huge savings but why is there such a huge range in the possible amount saved. I mean, you're talking on the one hand $1.2 trillion - that's not exactly a small number - but $4.2 trillion dollars is even bigger.

GIELEN: To calculate the savings, you have to look at what are the saved emissions, so there's a certain uncertainty there. You have to look at where will these emissions from these chimneys and these cars really affect people, so there is uncertainty. And then the question is, for example, how do you value health impact. So you have three uncertainties on top of each other, and as a consequence you end up with that range of $1 to $4 trillion but the key point is that the savings are at least a factor of five larger than the cost. So this makes sense.

CURWOOD: What you're talking about is a tall order, Dolf. To double renewable energy by 2030, how do we actually achieve this?

GIELEN: Well, one of the problems is perception. If you talk to a lot of people, they still have the feeling, oh, renewables are expensive. While, in fact, if you look at what has happened with the cost of solar PV in the last five years, we've seen an 80 percent, eight zero, cost reduction that is enormous, and it's not only PV, we see the same in wind, and we see the same in other renewables technologies.

CURWOOD: Now, what sectors do you find the most savings in?

IRENA included biomass energy in its analysis of how much money renewable energy could save the global economy. (Photo: Oregon Department of Forestry, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GIELEN: The power sector is clearly the most dynamic sector. Today, around 23 percent of global power generation is renewable, and we think that by 2030 that can increase to 45 percent, perhaps even more than 50 percent. The challenge is in the energy sector, so renewables in buildings for building heating, in the transport sector as a substitute for gasoline and in the industry sector, and their shares today are still relatively low and also there is need for much more action to come to much higher shares in these sectors.

CURWOOD: So which forms of renewable energy will we see the greatest increases, according to your study?

GIELEN: If you see at what's on the books today, you see very rapid growth in wind and in solar PV. So you see an increase of five maybe even tenfold between now and 2030, but they are starting from a relatively low share. On the other side, you have biomass, which accounts for three quarters of renewable energy use today. There we see less growth in percentage terms, but we still think that biomass can account for half of total renewable energy use in 2030 and also for a significant share of the absolute growth between now and 2030.

CURWOOD: Biomass is a big category. Can you just break that down for us a little bit?

GIELEN: On the supply side, residues are very important, so agricultural residues, forestry residues, and also post consumer waste. To some extent, you'll also see an increase in energy crops, dedicated energy crops. On the deployment side, it's a very versatile resource. You can use it for power generation, for heat, for liquid transportation fuels, and for aviation. There's an example of a sector where there is no other option available to take.

CURWOOD: Now, the fossil fuel industry is pretty well subsidized. How does that affect the ability for us to convert to the kind of energy systems that you say would give us these huge savings?

Dolf Gielen is the director of the IRENA Innovation and Technology Centre in Bonn, Germany. (Photo: IRENA)

GIELEN: Yes, you are absolutely right. In fact, the subsidies for fossil fuels are roughly four times as high as the subsidies for renewables worldwide, and that is in many countries a major impediment for accelerated deployment of renewables. At the same time, the falling costs for renewables mean that in more and more cases renewables are the most economic solution even without subsidies.

If you look at what has happened in the last year 2015, renewables accounted for significantly more than half of total global power generation capacity additions. For example, in solar PV, the addition was more than 50 gigawatts, it was more than total power generation capacity of Italy. If you look at wind, we added 64 gigawatts last year and we see growth rates of more than 20 percent a year in the application of these technologies and we think that this growth will continue.

CURWOOD: Dolf Gielen is director of IRENA’s Innovation and Technology Center in Bonn, Germany. Dolf, thanks so much for taking time with us today.

GIELEN: Thank you very much, Steve.

Related links:

- Download the IRENA report on doubling renewable energy capacity by 2030

- About IRENA’s Dolf Gielen

[MUSIC: L.A. Guitar Quartet, “4 Variations on Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” Winter Solstice On Ice, Mozart/arr.]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...more answers to the mystery of the Monarch butterfly’s decline. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from Wunder Capital, an online investment platform that allows individuals to invest in solar projects across the U.S. More information and account creation at Wunder Capital.com That's Wunder with a 'U'. Wunder Capital, Do well and do good.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: “Woodland Dance,” Woodland Dance, Joshua Messick and Acoustic Storm, CD Baby Alpha Music]

Suing to Save the Monarch

A monarch butterfly (Photo: bark, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. The steep decline in the North American Monarch butterfly population has won this spectacular creature its day in court. In March, two environmental groups filed suit against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for failing to protect Monarchs under the Endangered Species Act, and to compel the agency to set a date to address the matter. But not all the supporters of the creature think listing the Monarch as endangered is the way to go, as the Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports.

GRANT: Tierra Curry grew up in Appalachia, and remembers the mountains teeming with big orange and black Monarch butterflies. Today, she’s senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, and says the number of Monarchs has declined more than 80-percent from the twenty-year average.

CURRY: Back in the mid 1990s there were nearly a billion Monarchs, and the last two years, the population have been the lowest population sizes ever recorded.

GRANT: And Curry says they could easily be wiped out. In 2002, one winter storm killed more Monarchs than currently exist.

Tierra Curry, senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, says listing monarch butterflies as threatened under the Endangered Species Act would help protect the fragile insects. (Photo: courtesy of Tierra Curry)

CURRY: Because they all go to the mountains of Mexico for the winter and they cluster on these trees in this small area, they’re incredibly vulnerable to bad weather. And this year in particular with El Niño, they’re threatened by severe storms and by drought.

GRANT: Curry’s group, along with the Center for Food Safety, petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2014 to list Monarchs as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The agency launched a review. It’s supposed to take 12 months to decide. But 2015 came and went without a decision. And the environmental groups are suing.

CURRY: We want to get a legally binding date from the Fish and Wildlife Service, when they’ll make a decision whether or not to protect the Monarch under the Endangered Species Act.

GRANT: Georgia Parham is a spokesperson for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. She says Monarchs are one of many important species being reviewed for Endangered Species Act listing.

PARHAM: The Monarch petition is one of about 500 petitions that we are looking at.

GRANT: When someone petitions the agency to list a species, Parham says they look at how the species is doing, the threats to it, and how those fit with the listing criteria. And that can take a while. But she says it doesn’t mean nothing is being done.

PARHAM: A species doesn’t have to be listed for other federal agencies to start looking at it and planning for conservation. But with species like the Monarch, we’re out ahead of that.

Monarchs lay their eggs on the underside of the milkweed plant’s leaves in early spring (Photo: USFWSmidwest, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GRANT: She says Monarchs already get a lot of attention, in part because people miss seeing this once-common beauty in the backyard. And because President Obama prioritized Monarchs in his federal pollinator strategy. The government is working with Mexico and Canada, with states, and private landowners to rebuild habitat and plant milkweed - the only food Monarch caterpillars eat.

They need to restore tens of millions of acres of habitat, according to Chip Taylor. He’s an insect ecologist at the University of Kansas, and director Monarch Watch, a non-profit group working to help Monarch recovery.

TAYLOR: The federal government does not have enough federal land in the Midwest, even in the upper Midwest, to provide enough habitat on that federal land that would improve monarch butterfly numbers.

GRANT: Taylor says they need private landowners to get on board - to work with the federal government.

TAYLOR: We’re talking about very conservative areas of the country. Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, which are really important pivotal states for this monarch production.

GRANT: He thinks listing Monarchs under the Endangered Species Act - at top down approach - would be counter productive.

TAYLOR: I think what we would see here is that milkweed would disappear overnight. Nobody would want to have it on his landscape, simply because this would mean regulation. People don’t want regulation.

GRANT: But Tierra Curry at the Center for Biological Diversity wants a legally binding agreement on protecting monarchs, before a new president takes over in Washington.

CURRY: It’s possible that the next administration might not prioritize endangered species at all. And at that point it’s really important to have a legally binding date for this decision, or the decision could get put off forever.

GRANT: Curry expects to settle on a decision date with the Fish and Wildlife service on when a decision will be made about listing monarchs out of court. I’m Julie Grant.

CURWOOD: Julie Grant reports for the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- More about the monarch butterfly from the Center for Biological Diversity

- Monarch Watch

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: “Save the Monarch”

- Listen to the story on the Allegheny Front website

- About President Obama’s federal pollinator strategy

The Monarch Needs More Than Milkweed

Monarchs on a tree in Mexico (Photo: Anurag Agrawal, Cornell University)

CURWOOD: Hot on the heels of that legal push to protect this iconic insect comes a study that throws new light on the many threats that face the butterflies on their multi-generational migration from Mexico to the US and Canada and back. And this new study questions a key conventional wisdom about the role of pesticides and milkweed in the decline in Monarch numbers. It comes from a team led by Anurag Agrawal, a professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Cornell University.

AGRAWAL: Milkweed has been declining, certainly in the Midwestern USA where agriculture is most prominent, and with the increased use of herbicides and genetically modified crops that are tolerant of those herbicides, the amount of milkweed in those agricultural fields has declined. It certainly seemed quite logical that milkweed limitation could be playing a role in the population trends and the downward spiral of the monarch butterfly. Nonetheless, we were compelled to try to take a rigorous look at the data that are out there to ask the question, is that what's really going on.

CURWOOD: So what did you do?

Over winter, monarchs usually coat the sky in the valleys of Michoacán, Mexico. But their numbers have been declining. (Photo: Luna Sin Estrellas, Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

AGRAWAL: What we did was we really tried to put the pieces together, and what I mean by that is the monarch butterfly has a very complex annual migratory cycle. So in the fall they fly all the way down to Mexico, rest there for four months, fly back to the USA and then lay eggs in Texas and Oklahoma. From there, their offspring, or the next generation, flies up to the Midwest and the northeastern USA and Canada where they breed for two to three more generations.

We're very very fortunate to have many different datasets where citizen scientists and conservation organizations have been tracking the monarch populations, and it's one of the wonderful resources where people had the foresight 25 years ago to start these monitoring programs. By putting those different datasets together we were able to ask, “where is the weak point in the annual migratory cycle. Where is it that they are doing the worst?” and can we then take that information and infer what the problem might be.

CURWOOD: So, of course, we want you to give us the answer.

AGRAWAL: Yeah. What's very clear is that in Mexico, the highland overwintering grounds, the Monarchs cluster on these fir trees at about 10,000 feet elevation, their numbers have been declining over the past 20 some years. When they fly to the southern USA, we looked at the data, their numbers there have also been declining. But when we look at the next several generations of each cycle in the Midwestern USA, in the northeast, and as they fly south in the fall, none of those four independent datasets show any population decline over the past 22 years, and so that suggests to us that the monarch populations are building up each summer and the only time when they really rely on milkweed is the summer months when they are breeding, laying eggs, and the caterpillars only eat this food, and yet at the end of that time when they are done eating milkweed, their populations seem to be somewhat stable over the past 25 years. They then begin their southern flight. By the time they get to Mexico, the numbers are down again. So on the one hand that presents a very important finding. The decline seems to happen after they're done feeding on milkweed. It also presents the conundrum: why is it that their numbers are down when they get to Mexico given that they weren't down to begin with in the beginning of the fall?

CURWOOD: So, let me see if I understand this correctly. The problem area then is in some place between the southern United States and Mexico and the overwintering?

Monarch caterpillar on milkweed leaf (Photo: Ellen Woods)

AGRAWAL: The problem area - we don't exactly know and it spans several thousand miles which make this a bit of a gnarly problem, but it would appear that the problem has to do with being able to complete that flight successfully and establish in Mexico. From my perspective, that suggests I guess one of three potential problems.

They need flower nectar, the nectar produced by flowers, to power their flight to Mexico and it's entirely possible, there's been some work in the literature suggesting that the amount of flowers that are available for them to sugar up on, on that several thousand mile journey, have been reducing. If that's the case, they don't have enough energy and may not make it.

Secondly, they're traversing these tremendous distances and landscapes and they need those landscapes to be free of obstruction of insecticides, of poisons, etcetera, and it very well may be the case that they're not finding clean and healthy landscapes to do the migration.

Lastly, this is the concern for for several decades since the overwintering grounds in Mexico discovered in 1975 and we know they are highly highly restricted, 10 to 12 mountaintops, summing to the size of about New York City, that all of the Monarchs, the hundreds of millions of Monarch butterflies overwinter on these very special restricted dozen mountaintops. And there has been a consistent pressure on those forests in terms of logging and other human activities that have degraded those sites. It's been very difficult to pinpoint the impact of that forest degradation on the Monarchs, but it's quite clear that is substantial and despite best efforts to reduce logging and reduce those activities, some of it continues. And so I think it's the flower resources available, the uninterrupted and clean landscapes and the overwintering forests that may be contributing to their decline.

Monarch butterfly (Photo: Ellen Woods)

CURWOOD: And milkweed loss doesn't appear to be the culprit you're saying?

AGRAWAL: Our analysis of the data suggests that if milkweed loss is contributing, it's contributing in some complex way. What I mean by that is let's say with the impact of insecticides on Monarchs that are perhaps sublethal or just kind of making them slightly sick, and they're not finding enough host plants, together with, say, being slammed by a particular weather event, that could be causing their declines. But if we were to look across the 22 years that we have, is there a signal that reduced host plant alone is important for these butterflies, that signal does not exist, and I'd say its remarkably consistent across several different datasets.

CURWOOD: Hmmmm. Now, what about Mexico itself? You say of course the habitat, the dozen or so mountains there, that habitat has been degrading. How much habitat has been lost over these last 22 years?

AGRAWAL: Well over half of the Monarch...potential Monarch overwintering habitat I believe has been lost since the 1950s and 1960s and basically using aerial photographs. This is a very important study conducted about a decade ago, it was shown that a lot those habitats had been lost. There are certain ranges where Monarchs no longer go to overwintering, partly because they have been developed or the forest has been cut down. There were protections put into place by the Mexican government beginning in 1986, and since that time there have been various improvements or attempts to further protect the area. It's called the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve and its now a world heritage site has other important distinctions for its conservation value. But there's been a high-level habitat destruction and it continues, it continues at a relatively slower rate than in the past, but it continues.

The stages of a monarch butterfly’s emergence from is pupa (Photo: Ellen Woods)

CURWOOD: What role does mining play in this?

AGRAWAL: Mining plays some role and recently in the news, there was a New York Times article about this. There are deals being made and prospects of mining very close by to the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, and so that's something that has historically played a role and I think there hasn't been a lot of mining recently but it's again on the horizon and it's something we really need to look out for to make sure the government's making the right decisions in terms of allowing particular activities.

CURWOOD: So how do you think your research changes what we ought to be doing to protect this iconic species?

AGRAWAL: I think there's maybe two or three recommendations. The first thing I say is for those citizen scientists that are out there that are planting milkweed to improve habitat for the monarch, I would say please continue especially if you're planting native milkweeds. There's been some issues with non-native milkweeds actually causing some trouble, but if you can identify native milkweeds and plant them, not only will there be no harm, there probably could be some benefit of that.

Professor Anurag Agrawal and a friend! (Photo: JASON KOSKI/Cornell University Photography)

But to really address the problem of the long-term decline, I think we need to zoom out a little bit and ask is this decline specific to the monarch or are we seeing other species that are following a similar pattern and what does that tell us about the health and well-being of our continent. And the unfortunate truth is that many migratory species, and we have migratory birds, for example, that make the same or very similar trek, and many of their numbers are also declining in a similar way. That suggests a larger problem with the way we're managing our landscapes and those could be involving chemicals and pollution or it could be the fragmentation of the landscapes at a larger scale.

The reality for conservation of any species is that it's a very complicated endeavor and for the monarch butterfly we don't have a simple answer. I don't think that planting milkweed is going to solve the problem. Having said that, it raises the issue that it's a complicated problem in that climate, habitat, destruction, pesticides, host plant limitation etcetera all probably play some role. Perhaps one important message here is that there aren't quick fixes or simple fixes. Of course we should do more, we should plant milkweed, reduce the impact of pesticides on the environment etcetera, but it will not be a simple fix.

CURWOOD: Anurag Agrawal is a professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Cornell University. Thanks so much, Professor.

AGRAWAL: Thank you.

Related links:

- Anurag Agrawal’s lab at Cornell

- Read the article here

[MUSIC: “Woodland Dance,” Woodland Dance, Joshua Messick and Acoustic Storm, CD Baby Alpha Music]

CURWOOD: Coming up...science takes on the triple threats against coral reefs. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Tony Glover, “Don’t Let Your Right Hand Know What Your Left Hand Do,” The Return Of Koerner, Ray & Glover, Red House Records]

Beyond the Headlines

The Next Generation Science Standards have attracted opposition from some states because of reluctance to formally include climate change in curricula. (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture via Ford Elementary School, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Time to focus on the stories beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s with DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and is on the line from Conyers, Georgia. How’s it going, Peter?

DYKSTRA: It’s going all right, Steve. You know, the Next Generation Science Standards have been adopted in 18 states. They’re the new, unified approach to teaching science in schools. But the NGSS has endured a volley of lawsuits and legislative challenges, which is why it hasn’t been adopted yet in the other 32 states.

CURWOOD: Well, I would imagine that teaching climate science these days is a pretty big sticking point for some folks.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, but it’s not the only sticking point. The opposition is just as big to the teaching of another cornerstone of modern science, evolution. And there are a couple of coal-dependent states that actually have adopted the Next Generation Science Standards, even though the standards treat climate change as scientific fact, and those states are Kentucky and West Virginia.

CURWOOD: Well, perhaps it’s a bit counterintuitive, but in fact, Kentucky did educate John Scopes of that famous monkey trial and by a narrow vote, even refused to outlaw the teaching of evolution. So, tell me, Peter: where do the other states line up in terms of science education today?

DYKSTRA: I’ll give you a couple of examples. Wyoming is the biggest US coal producer, its legislature initially banned the new standards completely, then they revoked the ban, but that state hasn’t yet signed off on them yet. And another state with a brainy reputation that’s the home of both MIT and LOE hasn’t finalized things yet, either.

CURWOOD: Well, you gotta ‘love that dirty water’ here in Massachusetts! Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, a billionaire, a college professor, and a movie actor go into a bar, and get attacked…..

CURWOOD: Uh-oh, who are we talking about here?

DYKSTRA: Well, there’s no bar, of course, that’s just a cheap transitional device, but Billionaire Tom Steyer, Bill McKibben, and Leonardo DiCaprio are among the targets of a new campaign attacking high profile climate change activists.

The group America Rising Squared is attempting to cloud public opinion of prominent environmentalists, including actor Leonardo Dicaprio (shown above), activist Bill McKibben and billionaire Tom Steyer. (Photo: ABC/Rick Rowell, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hmmmmm. Now, who’s doing the attacking?

DYKSTRA: It’s the work of a nonprofit group with Republican National Committee roots called America Rising Squared. They’re gearing up social media, planning to follow the celebrities with cameras to post anything they might be able to make political hay out of, they’re running web ads and more. These are standard tactics on all political sides these days, and they’ve helped make this year’s campaign the bipartisan train wreck that it is.

CURWOOD: Yeah. Well at least something is bipartisan these days. But, seriously Peter, typically these tactics are used against candidates, not supporters.

DYKSTRA: Well, that’s not been forgotten here - Hillary Clinton takes her share of grief on the website, too. But from the looks of the early posts on the website, people like Steyer and DiCaprio will get attacked as fossil fuel hypocrites every time they board something with a bigger carbon footprint than a stagecoach.

CURWOOD: Ah, such is political life these days. Hey, what do you have from the history vault for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, what we call environmental journalism is about 40 years old. But possibly the first Pulitzer Prize for environmental journalism was awarded 75 years ago this week, long before environmental journalism was a thing. And the St. Louis Post-Dispatch won the Pulitzer.

Trains, homes and factories in St. Louis burned a particularly dirty kind of coal 75 years ago, until the city cleaned up its act after a local newspaper shed light on the problem. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: Ah, yes. Well, that was Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper, though he’d been dead for some thirty years by the time they got this prize.

DYKSTRA: Right, but this was classic public service reporting. They did a series on what was then called “The Smoke Nuisance”. Trains, homes, factories all burned coal – not just any coal, but a particularly dirty coal mined mostly in Southern Illinois. And the newspaper used editorials, editorial cartoons, news stories, and they even published an Anti-Smoke Roll of Honor for companies that had cleaned up their acts. All of which led to tighter, better-enforced municipal ordinances in St Louis and a more breathable city and a Pulitzer Prize.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and, of course, in that way they smoked the journalistic opposition, huh?

DYKSTRA: Ooh.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News - that’s EHN.org - and DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter, talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- E&E: “Inside W.Va.'s battle over teaching climate change”

- List of states that have signed off on the Next Generation Science Standards

- Politico: “America Rising targets Steyer”

- Digital archive: The St. Louis Post-Dispatch Wins a Pulitzer

- More about the Post-Dispatch’s Pulitzer-winning reporting

[MUSIC: Huun-Huur-Tu, “Interlude,” Where Young Grass Grows, improvisational xomuz, Shanachie]

Port Damages Miami Reef

Port of Miami (Photo: Lonny Paul, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Coral reefs are in the crosshairs of triple threats these days. The rise of CO2 associated with global warming is making the oceans more acidic, which can erode the calcium carbonate in coral skeletons. Global warming is also turbocharging the warming of the Pacific Ocean during the El Niño weather systems leading this year to massive die-off and bleaching of corals in the Great Barrier Reef off Australia, and in other parts of the Pacific. And commerce also threatens coral, and caused serious damage to the reef off Miami, Florida during a recent port expansion. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald has the story.

FITZGERALD: As the head of the Miami Waterkeeper, a big part of Rachel Silverstein’s job is to fight for the protection of the coral reef off the coast of South Florida.

SILVERSTEIN: It’s the only coral reef in the continental United States and it has declined by over 80% since the 1970s.

Corals buried by sediment (Photo: Miami Waterkeeper)

FITZGERALD: A lot of factors have contributed to that decline, from climate change and ocean acidification to agricultural runoff and disease. But coastal development is also playing a role. As the Panama Canal expands to accommodate larger container ships, Silverstein says that ports all along the eastern seaboard of the United States are following suit.

SILVERSTEIN: Port Miami was the first port in Florida to undergo a deepening and widening project in order to get ready to be able to accept these ships fully laden.

FITZGERALD: In 2013 the Army Corps of Engineers dredged sediment out of the channel and transported it out to sea. The corps said the process would have minimal impacts on the reef around the port, but new evidence suggests the dredging could have done serious damage to the corals by covering them with sediment. Andy Strelcheck is the Deputy Regional Administrator for the southeast fisheries division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. He says that in December of 2015 NOAA scuba divers assessed the impact of the dredging on a particular area of reef.

A Moray Eel on the Florida reef (Photo: Greg Grimes, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

STRELCHECK: We just surveyed nine sites north of the channel that were expected to be the greatest impacts and we were looking at sedimentation as well as any sort of signs of impacts to corals, coral reefs or other species on the reef. 1:40

FITZGERALD: Corals are animals, and can suffocate when covered up by sand, rock, and silt. The NOAA scuba divers found that hundreds of acres of reef had been buried in dredging sediment. At one of the 6 sites as much as 80% of the reef was impacted.

STRELCHECK: Sediment depths were greatest nearest the channel where the dredging was occurring and there was mortality of corals associated with sedimentation that occurred over a fairly broad area.

FITZGERALD: A December report commissioned by the Army Corps, stated that a bleaching event had been the primary cause of death for corals in Miami. Rachel says it was an attempt to downplay the role of the port expansion project.

SILVERSTEIN: There was bleaching and disease going on the region, but it didn’t explain how corals became buried in half a foot of sediment.

The Panama Canal is expanding to accommodate larger container ships, and ports in the US are following suit (Photo: Karen Sheets de Gracia, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

FITZGERALD: NOAA’S Andy Strelcheck says that he wants to finish surveying other areas around the port and work with the Army Corps of Engineers to begin reef restoration. But Rachel Silverstein also wants to make sure the Corps doesn’t repeat its mistakes. A similar port expansion project is scheduled to begin in Fort Lauderdale next year.

SILVERSTEIN: And so far the Army Corps has made promises that they won’t let the same thing happen again in Fort Lauderdale, but the documents that they’ve sent for Congress to support the authorization of this project were not one bit updated to account for what we know happened at Port Miami.

FITZGERALD: Miami and Fort Lauderdale are two of the cities in the US most vulnerable to sea level rise from climate change, and reefs provide natural protection that could help them cope with increased flooding.

Rachel Silverstein is Executive Director & Waterkeeper of Miami Waterkeeper. (Photo: Miami Waterkeeper)

SILVERSTEIN: These reefs that were destroyed are directly offshore of the city of Miami Beach, and they were protecting the coastline of the city of Miami Beach at the same time the city is spending hundreds of millions of dollars trying to pump the Atlantic Ocean off of its streets.

FITZGERALD: And Rachel Silverstein sees a value in South Florida's reefs that goes beyond the protection that they offer.

SILVERSTEIN: You know this is the only coral reef in the continental United States and you know I think it’s as rare and unique as the geysers of Wyoming or the sequoias or the redwoods in California, and I think it deserves the same level of attention and the same level of protection from our government and the public.

FITZGERALD: And with new research from the University of Miami showing that the Florida reef is already dissolving due to ocean acidification, there’s really no time to waste. For Living on Earth, this is Emmett FitzGerald.

Related links:

- Miami Waterkeeper

- NOAA Fisheries

Coral Bleaching in Kiribati

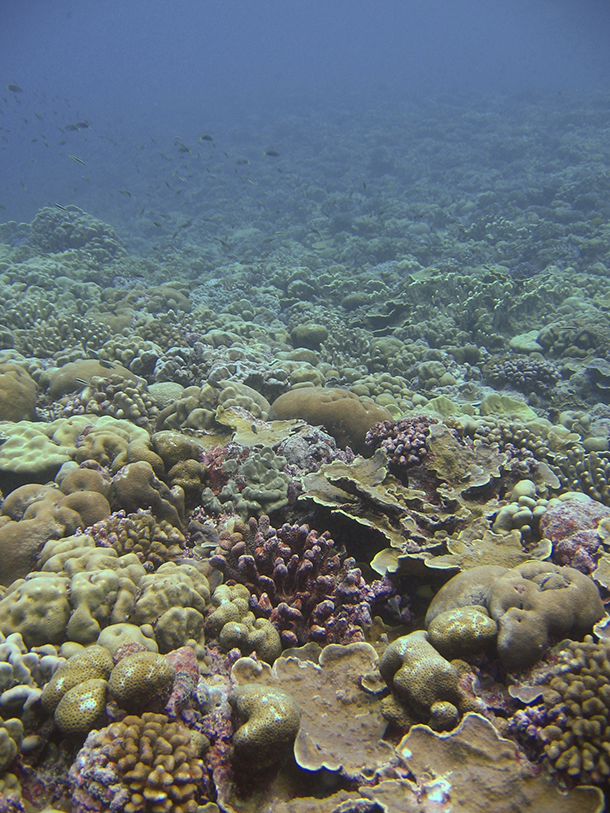

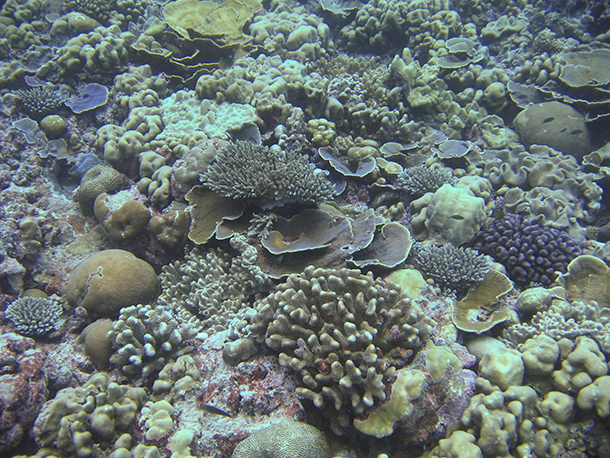

A healthy coral reef on Kiritimati, an island within the republic of Kiribati, hosts vibrant colors and active reef fish populations. (Photo: courtesy of Dr. Jessica Carilli)

CURWOOD: Scientists say as much as 92 percent of recent coral bleaching occurred in parts of the Pacific, thanks in part to El Niño. That led Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democratic Senator from the Ocean State, Rhode Island, to comment.

WHITEHOUSE: We’re seeing these incredibly frightening dramatic things happening things, like the die-off of the bulk of the Great Barrier Reef; these are not nothing, these are huge screams from Nature of warning.

CURWOOD: We’ll have more from Senator Whitehouse on our show next week, but now we have a first hand account of those bleached reefs are like. UMass Boston coastal geochemist Jessica Carilli studies how corals cope with climate change and pollution. She’s been diving for many years at Christmas Island, the largest coral atoll in the world, just 100 miles north of the equator and part of the Republic of Kiribati. This year, Professor Carilli sent her graduate student, Sean McNally, to check the reefs there and they’re both with us now to talk about corals and the future of our oceans.

Sean, you just came back from diving on Christmas Island. What do the coral reefs there look like?

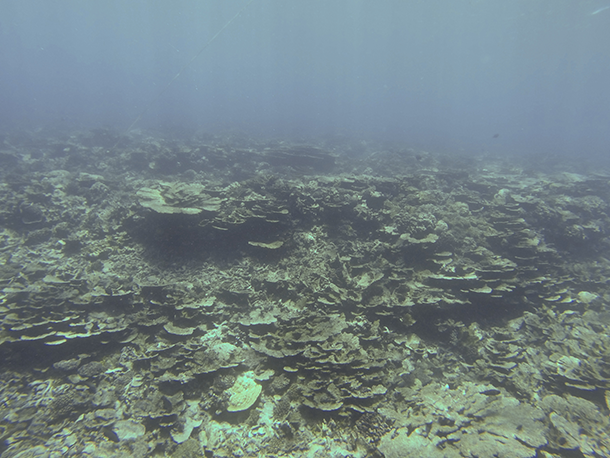

Sand and algae now cover a once-thriving coral reef community in Kiritimati, also known as Christmas Island. (Photo: courtesy of Sean McNally)

MCNALLY: It was pretty bad. Because of the recent El Niño event, we're seeing a lot of bleaching, meaning they're eventually maybe coming back or they might die. And it's pretty bleak when you go down there. You just see blues. You miss a lot of colors that corals can have underwater.

CURWOOD: What do these corals look like? I've been diving a bit and sometimes you get these brain like things and others are like fingers. These?

MCNALLY: Yeah, you explained it perfectly. So you have brain corals or mounding corals, which look like giant rocks. They're not rocks though, and then you also have fingerlike coral that branch out and they create almost like forest structures. Depending on the age of the coral, they can get pretty massive. It could be feet. We're talking a bus, the size of a bus, but they're colonial organisms so it's not just one organism. Through time they grow larger in a colony.

CURWOOD: It's a party.

MCNALLY: It's a giant party down there, literally.

CURWOOD: And it's rather colorful.

The view from an aircraft approaching Kirimati (Photo: courtesy of Sean McNally)

MCNALLY: Correct. So a healthy reef is extremely colorful, but what we're seeing on Christmas Island was that color disappeared because of the coral bleaching.

CURWOOD: What's really happening when we say that the corals are bleaching?

MCNALLY: So the corals live in an environment where they have a symbiotic relationship with Zooxanthellae which are brown algae that live in their tissues. A symbiotic relationship meaning that they get something in return from the Zooxanthellae, so they get sugars and essential nutrients to live off of, and the coral provides protection for them to live. Coral itself is an animal. It's not a plant and it just has plants that live inside of it, so when the waters get too hot the coral will expel its Zooxanthellae and it will eventually lose all of its color, and from there it'll lose its sugar source and will eventually die if they don't come back. So right now we're tracking coral resilience through this natural bleaching event in Kirabati, and we're looking at if corals that have larger lipid stores, or fat stores, will be more resilient to coral bleaching through this extreme climatic event.

CURWOOD: How do you feel when you see a bleached coral?

MCNALLY: I feel pretty bad, but I when I started coral studies about four or five years ago and I have not been lucky enough to see an extremely healthy reef in my studies.

CURWOOD: Sean, stick around. I want to talk to your professor, Jessica Carilli, for a few minutes.

MCNALLY: Sounds good.

CURWOOD: Professor, this bleaching sounds really alarming. How does the state of corals that Sean described compare to what you've seen in your visits to Kirabati in the past?

Almost 80% of the reef sites surrounding Kiritimati have died because they were not able to recover after bleaching under extreme temperatures brought about by the 2015-2016 El Nino event.(Photo: courtesy of Sean McNally)

CARILLI: Well, the last time I was on Christmas Island was in 2010, and I went to a lot of sites around the island, and they were some of the most beautiful reefs that I've seen with extremely high coral cover, very, very high diversity. The pictures that I saw from Sean's recent trip were extremely sad because most of the coral is now dead. Up to 90 percent has already died and become covered in algae, which is just devastating.

CURWOOD: Why are corals so essential?

CARILLI: Corals are basically trees. They provide habitat for thousands, millions of other creatures. They are some of the most diverse ecosystems anywhere on the planet, they provide seafood, they also buffer islands from storms. They create islands. Coral atolls are made of broken up pieces of dead corals. They're also a potential source of medicines because of their high diversity, and they take care of water quality. Places with healthy coral reefs have better water quality, less microbes in the water and this is good for human health.

CURWOOD: The coral cleans the water or the coral needs clean water?

CARILLI: A little bit of both. Corals are also are really impacted by runoff from land. That's another thing that we study in my lab. Land based runoff is not a huge problem in places like Kirabati in the middle Pacific, but in other parts of the world runoff can be a significant problem and we think that runoff, for instance from farm or from industry, can exacerbate coral bleaching.

CURWOOD: So how likely is it that these corals can recover from this bleaching?

CARILLI: Well, the corals that have completely died, they can't recover, but the reef as a whole can hopefully recover if it's repopulated by baby corals and that depends on a few things: the availability of baby corals to come to this island from elsewhere where the corals didn't die or possibly from deeper down - corals are surviving deeper - and also depends on the availability of suitable places for the baby corals to settle back on the reef. So the fact that everything has been covered in algae is a bit of a problem for that. Baby corals don't like to settle on fleshy algae, so I'm not sure. The prospects don't seem great, but I'm always trying to maintain hope.

CURWOOD: What about the corals in the Persian Gulf that seem to be able to tolerate a lot more heat than your typical coral. What's different about them and how might this be of help in the future of Kirabati?

CARILLI: So corals in different parts of the world are adapted to their local conditions. So in the Persian Gulf, waters are normally very, very warm, and so the corals there have adapted to those temperatures partly because of the coral animal itself having a different physiology and partly because they host more heat resistant algae. So, this gives us a little bit of hope. We have seen some evidence that corals after bleaching can acquire heat resistant algae, similar to the algae that the corals in the Persian Gulf host, and so this might allow corals to survive future bleaching events. There's also work going on where people are actually trying to genetically engineer more resistant corals that we could plant onto reefs to survive future warming, for example.

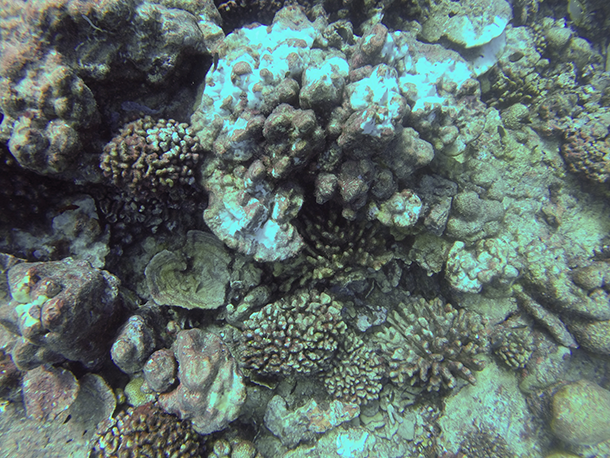

Designating marine protected areas; reducing runoff; feeding corals; and even deploying shade structures could help corals make it through bleaching events. (Photo: courtesy of Sean McNally)

CURWOOD: What if anything can be done to make corals more resilient to climate disruption?

CARILLI: There's a number of ways that people are trying to address this problem and try to help corals survive climate change. One of them is by just protecting different areas so creating something called a Marine Protected Area where, for example, people aren't allowed to fish, and they hope that that will reduce some sort of stress on a coral so that it can survive climate change. Other more local impacts that we can do is reducing run off. There's good evidence that reducing runoff will allow corals to have the upper hand to survive stressful events like bleaching.

But then there's also a lot more directed things that humans are doing. We're starting to think about actually going out and deploying shade structures during bleaching events to try to reduce the sun stress that combines with the heat stress to exacerbate bleaching, and with the work that Sean and I are doing, we're trying to answer the question that are fed corals better able to survive a bleaching event, can we just go out there and give them another food source while they are missing their symbiotic algae, if they can feed on zooplankton, can they survive?

CURWOOD: Professor, what originally drew you to corals?

CARILLI: Well, I started out studying ice cores. I've always been really interested in using natural archives to reconstruct change through time, and I've also been really interested in how humans are changing the world, and corals sort of lend themselves to these kinds of studies because we can reconstruct physical change from, for example, the chemistry of the coral skeleton and then we can also look at how those physical changes have affected the coral, for example, by looking at how their skeletal growth rates have changed through time. So corals are sort of a beautiful organism to study because they live a long time and they record change through time and allow us to look back at how things have changed in places that we didn't think to study.

Sean McNally, PhD student (left), and Dr. Jessica Carilli, coastal geochemist (right), in our studio at the University of Massachusetts Boston. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: How long do corals live?

CARILLI: They can live for hundreds of years. Individual corals and coral reefs themselves can have records that extend back many thousands of years if you look back into the fossil records.

CURWOOD: Sean, what's cool about corals?

MCNALLY: Everything. The ocean is pretty amazing. So if we were to go down in a glass bottom boat, we would see crystal clear blue water, you would see hundreds of species of fish and you'll see tons of different coral species that are branching, that are boulders, it's just forest underwater essentially and there's so many questions that you can ask and it's just endless.

CURWOOD: Sean McNally is a PhD student in marine science at UMass Boston. Jessica Carilli is an Assistant Professor of coastal geochemistry in the School for the Environmental at University of Massachusetts, Boston. Sean, Jessica, thank you both for being here.

MCNALLY: Thank you very much.

CARILLI: Thank you as well.

Related links:

- More on coral survival

- The Carilli Lab at UMass Boston: Human Impacts on Coastal Ecosystems

- About the Cobb Lab

- New York Times: Corals around the world are threatened by bleaching

- The Guardian: Bleaching in the barrier reef made likelier by Climate Change

[MUSIC: Madredeus, “Os Moinhos (Windmills),” O Espirito Da Paz, Metro Blue Records]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, another call to probe Exxon’s alleged climate fraud.

WHITEHOUSE: The CEO of Exxon may say nice things at a Davos cocktail party, about climate change being real and Exxon being interested in a carbon price, but down at the American Petroleum Institute, where they lobby, they're telling people "don't believe that. You cross us and you're toast."

CURWOOD: That’s Rhode Island Senator Sheldon Whitehouse next time, on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Madredeus, “Concertino-Allegro,” O Espirito Da Paz, Metro Blue Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Peter Boucher, Adelaide Chen, Jaime Kaiser, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth.

And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes fom the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth