September 9, 2016

Air Date: September 9, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

U.S. And China Ratify Paris Agreement

View the page for this story

The two nations with the most global warming emissions have now ratified the landmark Paris Agreement, with other countries expected to follow. Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientists and host Steve Curwood discuss how more nations representing at least 10 percent of emissions need to ratify to bring the accord into force, and how the 2016 US presidential election could impact this landmark climate pact. (07:05)

Dakota Pipeline Fight

/ Jaime KaiserView the page for this story

Native Americans have been protesting a planned oil pipeline slated to cross the Missouri River in North Dakota. The Standing Rock Sioux Nation says the construction threatens their drinking water and infringes on their historic lands, but petroleum officials say the project is a safe way to transport a valuable American asset and would bring jobs. Jaime Kaiser reports. (06:55)

Eminent Domain For Pipeline Profits

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

Fracking companies in the Pennsylvania region want to expand their network of pipelines for the export of liquid byproducts of natural gas such as ethane and butane, used to make plastics. Allegheny Front reporter Julie Grant investigates the legality of the industry’s claim to private land under eminent domain, given claims that these byproducts serve profits much more than public good. (07:00)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s Beyond the Headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about bans on certain antibacterial soap and sunblock ingredients and some hope for the Tasmanian devil, which has been largely wiped out by a contagious cancer. In the history calendar, it’s 100 years after the opening of the first supermarket. (04:25)

Avian Malaria Flies North

View the page for this story

Biologists have found the first New Hampshire common loon dead from avian malaria, a tropical disease carried by mosquitoes. Writer Derrick Jackson shares his concern about how the warming climate is putting northern bird species at risk of contracting tropical diseases. (02:40)

BirdNote: Common Mergansers

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

A large water bird known as the Common Merganser is often mistaken for a loon, as Michael Stein reports in today’s BirdNote. That’s because they share many physical traits, but the merganser has one adaptation that gives it an edge in catching fish. (01:50)

The Fever of 1721

View the page for this story

The worst smallpox epidemic in Boston history was a turning point for control of the disease in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. According to Stephen Coss, author of The Fever of 1721, it also helped set the stage for the American Revolution and freedom of the press. Coss tells host Steve Curwood how the knowledge of a slave, the epidemic and political unrest influenced the lives of Cotton Mather, Benjamin Franklin, and an influential Boston physician, Zabdiel Boylston. (16:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Alden Meyer, Stephen Coss

REPORTERS: Julie Grant, Peter Dykstra, Derrick Jackson,

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Global warming is scarcely mentioned during Presidential campaign events, but the US and China have taken a momentous step by ratifying the UN Paris Climate Agreement.

MEYER: It's a very big deal, because to take effect, Paris needs to be ratified by 55 countries representing 55 percent of global emissions. The US and China bring us up to 26 countries, but importantly they bring us up nearly to 40 percent of global emissions.

CURWOOD: What comes next. Also, Native Americans make a stand to protect their ancestral lands from a Bakken oil pipeline.

GOLDTOOTH: When the Corps of Engineers was doing their survey of the land, they never consulted the tribes on it. I mean the tribes are the ones who know where these sacred and cultural significant sites are.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

U.S. And China Ratify Paris Agreement

President Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping greet each other at the G20 Summit in Hangzhou, September 2016. (Photo: Pete Souza / Official White House Photo)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. US President Obama and Chinese President Xi have formally ratified the Paris climate Agreement. This landmark moment in international relations took place as heads of state were gathering at the recent G20 meeting in China. Climate diplomacy expert Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientists is here to put the ratification in context. Alden, welcome back to Living on Earth.

MEYER: Good to be with you again, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, how big a deal is this? How significant is it that China and the United States, the countries with the two largest economies in the world have now ratified the Paris Agreement?

MEYER: It's a very big deal because, to take effect, Paris needs to be ratified by 55 countries representing 55 percent of global emissions. US and China bring us up to 26 countries having taken an action to join Paris. Most of the rest are small islands and vulnerable countries. But importantly they bring us up nearly to 40 percent of global emissions. There's a number of them that are either taking action or signaling they will take action by the end of this year. Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Canada, Australia, Ukraine, and the latest estimate is that we'll have somewhere between 55 and 60 countries representing almost 60 percent of global missions to push us over that finish line and have Paris taking effect.

CURWOOD: And, of course, the end of the year is important to us in terms of American politics. Donald Trump has vowed to abandon the Paris Agreement if he wins the White House in November. If this has been all agreed to do before he takes office, to what extent could he derail this process?

MEYER: Well, if the agreement has entered into force before as it's likely to, it would be four years before the US could formally withdraw under the terms of agreement. That's not the big question. The big question is would Donald Trump take any action to live up to the US commitments under Paris, and the answer from his statement seems to be no, that he would not push to decarbonize the US economy, to shift away from coal and other fossil fuels and the renewables and all the other steps that President Obama has been taking. So, I think that is what is raising real concern among other leaders and organizations around the world. It's not whether he would formally withdraw the US from the agreement, it's whether he would lift a finger to live up to our commitments under it.

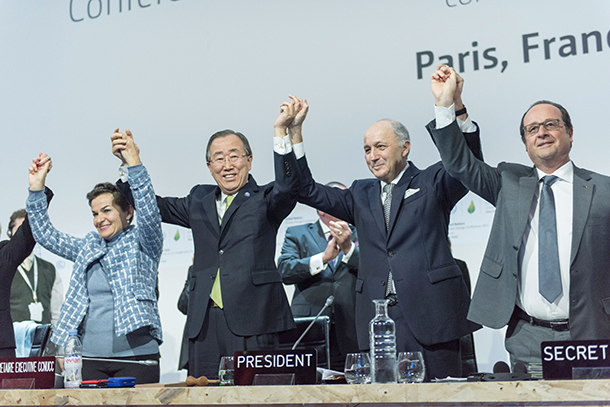

The leaders of the Paris Agreement celebrate its adoption at COP21 in December 2015. From left: Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Christiana Figueres; Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon; President of COP21 Laurent Fabius; and French President François Hollande. (Photo: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Of course, right now, the President of the United States is Barack Obama. Why did President Obama and the Chinese President Xi choose this moment to ratify?

MEYER: Well, I think they wanted to continue the leadership that their two countries have been showing over the last several years. It was really in the fall of 2014 that the first US-China agreement brokered a real breakthrough here and I think laid the groundwork for the Paris Agreement itself because, of course, you remember back in Copenhagen the two countries were at loggerheads and really pointing fingers at each other and the rhetoric was getting quite intense. So the fact that the US and China have in working together on implementation of Paris and choosing this moment right before the G20 summit of world leaders in Hangzhou, China, I think was very significant. And of course both of them are encouraging other leaders in other countries to join them in implementing Paris.

CURWOOD: Some folks ask how President Obama's been able to single-handedly ratify the Paris Agreement without having to go to the US Senate.

MEYER: Well, under our US law and tradition all the way back to George Washington, there are a number of actions that the president has taken on international agreements over the years, and it's clear that with the Senate having ratified the underlying treaty, the Rio treaty back from 1992, under George H. W. Bush, that the president has authority to adopt this agreement in Paris which is basically implementing that treaty that was ratified by the Senate. And of course he is acting under existing authority, the Clean Air Act and other laws that the Congress has passed, and the Supreme Court has upheld, to move forward on implementation, domestic actions needed to meet the commitments that he made in Paris, the 26 to 28 percent emissions reduction below 2005 levels by 2025. So, on both the international side and the domestic side, the administration is claiming it has the authority under previous congressional action to join the Paris Agreement.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry signed the Paris Agreement at the United Nations headquarters in New York on April 22nd, 2016, his granddaughter in tow. (Photo: Amanda Voisard / United Nations, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Some Republicans are saying “No.” What's their best argument?

MEYER: Well, I mean I think on one hand they say the President doesn't have authority to do this and on the other hand they say, “Well other countries aren't joining us and it's not going to be significant anyway,” and I think one of the political impacts of US China agreement is to undercut that argument that we're on our own here and others won't join us.

CURWOOD: So, the United States in Paris said, look we have the Clean Power Plan that we’re going to move forward with. That now seems to be in jeopardy. So where are we now then in terms of meeting our obligations under the Paris agreement, do you think?

MEYER: Well, I mean, the Clean Power Plant, of course, there was a stay put on it by the Supreme Court in a 5-4 decision that was not a ruling on the merits. The Clean Power Plan will be up before the appeals court here in DC, the Circuit Court later this month. It's expected to survive that challenge and likely will go to the Supreme Court next year, and of course there it partly depends on the outcome of the election and who takes the seat vacated by the death of Antonin Scalia. Most states seem to be going forward with preparing to implement their obligations under the Clean Power Plan, so that shows you I think where their betting is. It's a pretty good news story if you look back over the last eight years domestically on what the President's been able to achieve.

CURWOOD: Alden, before you go, give me the big picture here how on track are the world's nations in terms of tackling climate disruption at this point?

Alden Meyer is director of strategy and policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists and the director of its Washington, D.C. office. (Photo: Union of Concerned Scientists)

MEYER: Well, I mean there's good news and bad news. The good news is that there is unprecedented investment in clean energy and renewable energy and energy efficiency, and the costs of those technologies are coming down, and it looks like we may have reached a global peak in emissions and starting to bend the curve downward. The bad news of course is that there's still a fair amount of investment in conventional fossil fuels, coal plants and other technologies and of course, the real question is, will we decarbonize the global economy quickly enough to stay out ahead of the physical impacts of climate change, and of course there the jury is out. We really are in a race with the physical climate system, and of course we're seeing mounting impacts of climate change by the week.

CURWOOD: Alden Meyer is Director of Strategy and Policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much for taking the time with me, Alden.

MEYER: Good to be with you, Steve.

Related links:

- Paris Agreement -- Status of Ratification

- Reuters: “U.S., China ratify Paris climate agreement”

- Hindustan Times: “India could get more time to ratify Paris climate agreement”

- Listen to LOE’s previous coverage of the Clean Power Plan stay

- About Alden Meyer

Dakota Pipeline Fight

A section of the Dakota Access Pipeline in Salem, North Dakota. If completed, it will be 1,172 miles long and could carry half of the light sweet crude oil produced by the Bakken Shale. (Photo: Tony Webster, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: As US oil output has increased, companies are faced with a problem. Getting crude from the fracking fields to market. Trains are overloaded and vulnerable to fiery accidents, so some want to build more pipelines, and those bids can spark passionate opposition. The latest flashpoint is the Dakota Access Pipeline, a $4 billion project to carry over half a million barrels of crude oil per day out of the Bakken Shale. Hundreds of Native American protestors have mounted fierce demonstrations, fueled in part by outrage at the proposed 1200 mile route that would cross the Missouri River and ancestral lands. Opponents say the route was approved by the Army Corps of Engineers in violation of federal laws meant to protect clean drinking water and preserve ancestral tribal lands. Living on Earth’s Jaime Kaiser has our report.

[CHANTING, YELLING]

PROTESTOR: This is a new warrior, a true warrior who stands up for our rights. Rights that Native Americans have paid for in blood. They made the constitution out of a lie. A lie to the world. We have the right to assemble.

[CHANTING]

KAISER: The standoff against the Dakota Access Pipeline between local authorities and protestors led by the Standing Rock Sioux Nation have been going on for weeks. The flash point is the construction site by the Missouri river where The Army Corps Of Engineers approved permits in July to build sections of pipeline that will pump barrels of crude oil from the Bakken shale in North Dakota across South Dakota, Iowa, and Illinois to East Coast markets. The Sioux filed a lawsuit against the Army Corps of Engineers alleging that the permits violate federal law. On September the 6th, Judge James Boasberg put a temporary halt to the construction on some portions of the line, but not the section west of Lake Oahe that contains the sacred Sioux places.

The Sioux and Lakota peoples have received an outpouring of support for their campaign to halt construction on their ancestral lands. (Photo: Peg Hunt, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

GOLDTOOTH: One of the issues that the tribe has raised time and time again is that when the Corps of Engineers was doing their surveys of the land, they never consulted the tribes on it. I mean the tribes are the ones that know where these sacred or cultural significant sites are.

KAISER: That’s Dallas Goldtooth of the Indigenous Environmental Network, an active participant in the Dakota Access protests. He explained that the location of the line under dispute is a choke point for the project.

GOLDTOOTH: Construction has not started across the Missouri. For those of us who have been fighting this pipeline for the past couple of years see the strategic value of stopping it at the river.

KAISER: Some opponents call this pipeline the “black snake” and say it’s proposed to slither about a mile from Sioux territory, but right within traditional lands. Conflict reached a boiling point over Labor Day weekend when builders attempted to kick-start construction, allegedly desecrating tribal artifacts in the process. After heated physical confrontations, the trucks left.

PROTESTER: They are bulldozing. They are bulldozing and preparing to install a pipeline they’re going deep under the river.

[SHOUTS, SCREAMS]

PROTESTOR: This land belongs to the Earth. We are only caretakers. We’re caretakers of the Earth.

The planned pipeline route crosses the Missouri River about a mile from the Standing Rock Reservation. (Photo: Jimmy Emerson, DVM Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

KAISER: But the pipeline fight is a two-sided coin, because it will bring jobs and access to a valuable US resource. Here’s Tessa Sandstrom of the North Dakota Petroleum Council, a trade association that includes pipeline builder Energy Transfers.

SANDSTROM: There will be 8,000 to 12,000 jobs created during the construction, the majority of which will be made up of locals from the North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota area. They are working with the laborers unions here to help provide some of those jobs and so it’s really going to be a significant boon, especially during this current downtime.

KAISER: Another argument Tessa Sandstrom offered was that the strong safety record of moving oil via pipeline compares well with other modes of transportation like rail. That can lead to flaring disasters like the Lac Megantic explosion in Quebec that left 47 dead. Here in the U.S., oil rail incidents increased nearly sixteen-fold between 2010 and 2014.

SANDSTROM: And pipelines of course do remain the safest way to transport materials whether it’s crude oil, water, gasoline refined product. They have a very high safety record and Dakota Access particularly is going above and beyond what the Federal government requires to assure that it remains safe to operate and to get our resources out to market.

KAISER: But for activists like Goldtooth, the question of whether to transport oil by train or truck or pipeline is irrelevant.

GOLDTOOTH: It’s a set-up. It’s a set-up question because its foundation is based on the belief that we have to keep on drilling, that we have to keep on extracting, that we have to continue to be dependent upon this extractive economy.

The Sioux demonstrators and their allies have established “Sacred Stone Camp” to collectively protest the Pipeline project. (Photo: Joe Brusky Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

KAISER: The Army Corps and the pipeline company refused comment. In addition to the many federal regulations that the Corps of Engineers is accused of ignoring, approving the project without Native American consent could very well violate international law, including the 2007 U.N. Declaration of Indigenous Rights.

DOROUGH: My name is Dalee Sambo Dorough, and I’m an assistant professor at University of Alaska Anchorage but I’m also an expert member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

KAISER: Dalee herself is a member of the Inupiaq, or Inuit Alaska Native people, and she believes that the Standing Rock Sioux Nation was not adequately consulted under international law.

DOROUGH: There are a number of different relevant international human rights instruments. In my view, The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as well as the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights are directly relevant.

KAISER: Dorough says she has not noticed improvement in respect fot the rights of indigenous peoples since the adoption of the UN Declaration in 2007.

DOROUGH: What we’re seeing is an increased number of violations being perpetrated against indigenous peoples not only in North America but throughout Latin America, especially in the area of extractive industries. Unfortunately it’s been a consistent march forward to exploit indigenous peoples land, territories, and resources.

KAISER: That’s what the Standing Rock Sioux Nation and their allies allege is happening in this case, but Dallas Goldtooth says that they will keep fighting.

GOLDTOOTH: We have a lot of faith and a lot of prayer that’s happening in this camp and so I have to trust in that prayer and trust in the collective energy that we all are giving.

KAISER: As they point out, their heritage and sacred places, once destroyed, are gone forever. For Living On Earth, I’m Jaime Kaiser.

CURWOOD: On September 9 the Obama Administration ordered pipeline construction halted in the federal region in question while the Justice Department, Interior Department and Army Corps of Engineers conduct additional reviews.

Related links:

- Standing Rock Lawsuit against the Army Corp of Engineers

- Company Information on the Dakota Access Pipeline

- Army Corp of Engineers Permit Review Process

- The North Dakota Petroleum Council

- Protest audio courtesy of Mike Bluehair

- Labor Day Weekend audio courtesy of Democracy Now Newshour

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Dallas Goldtooth’s Keystone XL fight

[MUSIC: R. Carlos Nakai Quartet, “Go ‘Round Mary,” Big Medicine, Canyon Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, how infectious disease is blurring the lines between tropical and temperate forests. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[MUSIC: R. Carlos Nakai Quartet, “Go ‘Round Mary,” Big Medicine, Canyon Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, how infectious disease is blurring the lines between tropical and temperate forests. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Childsplay, “Queen Maeve’s Slumber,” Waiting For the Dawn, Sheila Falls-Keohane/arr.John McGann, Childsplay Records]

Eminent Domain For Pipeline Profits

Mick Luber, an Eastern Ohio farmer, has had to contend with multiple natural gas companies such as Marathon and Kinder Morgan that want to route their pipelines through his farm. (Photo: courtesy of Julie Grant)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Fossil fuel pipeline projects continue to attract controversy, especially when companies persuade governments to invoke the power of eminent domain to take people’s land. Companies argue that natural gas access is a public good, but when the proposed pipes would carry by products of fracking such as propane, butane, or ethane - some landowners are fighting back, saying these products are not in the public interest. Julie Grant of the Allegheny Front has the story.

[CICADAS]

GRANT: The quiet hills of Eastern Ohio, in Harrison County, have become a popular spot. And not just for the cicadas you hear - but also for oil and gas development. Mick Luber grows his tomatoes, greens, even fava beans here, at his organic farm, and sells them at markets in Pittsburgh and Wheeling. He says recent years have brought a compressor station and multiple well sites so close, they wake him up at night.

Natural gas storage facilities like these are becoming more prevalent with a burgeoning demand for natural gas liquids. (Photo: Bilfinger SE, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

LUBER: For the first year that they were fracking, it was hard for me to go outside. I felt so bad hearing the roar of all this stuff. It’s nice to have the cicadas that drown them out.

GRANT: Now pipelines companies, like Kinder Morgan, are showing up. They came knocking on Luber’s door…

LUBER: They wanted to come right down through this main field, and go up over the top of that hill. There’s a spring right up there. That’s the most fertile part of this farm.

GRANT: Marathon is already building a pipeline on the southern border of his farm. Luber points up to the valley, where pipes are lined up, waiting to be connected. The ground has been stripped bare.

LUBER: This is what you end up with. This was all woods.

GRANT: Shell is also planning a line here. So when Kinder Morgan showed up, Luber said no. No pipeline, not even a survey.

LUBER: I told them I didn’t want it.

GRANT: Kinder Morgan sued. One of the main arguments in Luber’s defense: the contents of Kinder Morgan’s pipeline. Not natural gas for home heating, but to send ethane to Canada for NOVA Chemicals to make plastics. Ethane, along with propane, and butane, are known as natural gas liquids. They’re by-products of natural gas that’s being fracked in the region. Increasingly, landowners are arguing that they shouldn’t have to give up their property rights for companies to transport these liquids to make plastics, especially if they’re being sent to foreign countries.

Kinder Morgan spokesperson Allen Fore says, “Yes, they should. Plastics are in the public interest.”

FORE: But you tell me anybody in this country that doesn’t use plastics in some way, and that plastics aren’t critical to their everyday lives, from cups to medical devices, to automobiles.

GRANT: You might think the federal government would have a say in whether transporting these natural gas liquids to make plastics is important enough to usurp individual property rights. If this were a natural gas pipeline, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, FERC, would also have authority over siting its route. But what about these liquids, like ethane?

RAIDERS: FERC has no authority to regulate natural gas liquids in the United States. At all.

GRANT: Attorney Rich Raiders represents about a dozen landowners in Pennsylvania against eminent domain action from a different pipeline company, Sunoco Logistics. He says when FERC has authority, as it does for siting natural gas pipelines, landowners are part of the routing discussions.

RAIDERS: That’s an all public, eyes-open discussion. Whereas for a natural gas liquids line that’s between the individual landowner and the pipeline operator, and no government entity is involved at all.

GRANT: Well, the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration does require permits for large earth disturbances and around bodies of water for pipeline routes. But when it comes to eminent domain, that’s being decided in state courts.

The Kentucky Supreme Court recently let a lower court ruling stand. It found that the pipeline company in that case is not a public utility, which means it doesn’t have the power of eminent domain to site a natural gas liquids pipeline. In Pennsylvania, pipeline companies that want eminent domain power also have get certified as a “public utility,” by the state Public Utility Commission, the PUC. To do that, they have to show that their project will benefit the people of the Commonwealth. And what that means, is under debate.

Natural gas companies often invoke eminent domain to build pipelines through private holdings. (Photo: Public Herald, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

One of the biggest headline grabbers on this issue has been Sunoco’s Mariner East project. It includes two pipelines - an older one that’s been repurposed and newer one, both carrying natural gas liquids. The new line begins in Ohio, near Mick Luber’s farm in Harrison County, runs through Pennsylvania to the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex, on the Delaware border near Philadelphia. From there, Raiders says the propane is being shipped to Europe.

RAIDERS: That’s not a need of the Commonwealth.

GRANT: And so he argues Sunoco should not have the power of eminent domain. The company would not record an interview for this story. In an email, Sunoco says the project will provide propane for heating fuel to markets in Pennsylvania. Sunoco says the Mariner East 2 pipeline it’s a utility, based on certification granted by the PUC to their older pipeline back in the 1930s. Some are fighting that stance in court. And a state appeals court recently sided with Sunoco. Pennsylvania’s Commonwealth Court ruled in July that the company is a public utility, and that that power extends to all 17 counties along the contested pipeline’s path. Sunoco’s email says, still, they’ve come to agreement with the majority of landowners.

Attorney Nicholas Anderson represents a landowner in Harrison County, in Ohio. The Teter family is fighting Sonoco’s eminent domain action.

ANDERSON: The bottom line is when they’re approaching landowners in Ohio, they have this big stick called eminent domain. And so they say, “Look, we’ll give you X number of dollars per linear foot. But if you don’t accept that, we’re just going to take your property. And that is where we have a problem.”

The compound known as ethane serves as the building blocks for many different materials, including commercial plastics. (Photo: zeevveez, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GRANT: Anderson’s Ohio clients lost their court case against Sunoco, but they’re appealing.

Anderson says along that Kinder Morgan ethane pipeline from Ohio to Canada, the one farmer Mick Luber was fighting, the company recently filed 130 eminent domain cases in at least eight Ohio counties. Kinder Morgan spokesperson Allen Fore says they only take eminent domain action as a last resort.

FORE: If you look at our route, you can see a lot of zigs and zags and turns, certainly not a straight line. Those are all based upon big issues like avoiding environmentally sensitive areas, or individual landowner concerns.

GRANT: Like Mick Luber. Kinder Morgan recently announced they would re-route around his farm. Still, Luber doesn’t see it as a victory.

LUBER: Well, as long as these guys are still doing this stuff, what is the victory? You know, you can’t stop the vigilance. People have got to keep standing in their way.

GRANT: Kinder Morgan says, Luber got what he wanted. But the company wants to make it clear, they can’t re-route for every landowner who has a problem with their pipeline. I'm Julie Grant.

CURWOOD: Julie reports for the Pennsylvania public radio program, The Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Natural Gas liquid information

- The Kinder Morgan pipeline that Mick Luber fought

- Sunoco Mariner East project summary

- Utopia Pipeline lawsuit

- Reporter Julie Grant’s Allegheny Front bio

[MUSIC: Glen Velez, “Origins (First Chakra),” The Rhythms Of the Chakras, Sounds True Records]

Beyond The Headlines

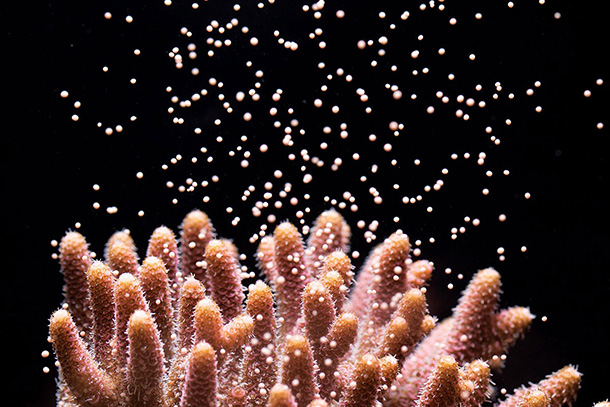

In an effort to protect sensitive coral larvae, Hawaiian state legislators are considering a ban of sunscreens that use the chemical oxybenzone. (Photo: Penn State, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let’s head beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter is with DailyClimate dot org and Environmental Health News, that’s e-h-n dot org and joins us from on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Let’s start with three common consumer goods that may see big regulatory changes soon. First, the US Food and Drug Administration has banned antibacterial soaps containing triclosan, saying the chemical is no more effective than ordinary hand soap and may actually hold some risk as a potential endocrine disruptor.

CURWOOD: Hmmmm, well that’s been a very long battle.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, FDA first proposed a review of Triclosan back in 1978, but their decision last week isn’t the end, since it still allowed for use in some hand sanitizers, cosmetics, and even some toothpastes.

CURWOOD: Huh, toothpastes, so you won’t be able to put Triclosan on your hands, but you’ll still be able to put it in your mouth? What’s next?

DYKSTRA: Another long-running environmental battle – the UK government says it plans to ban plastic microbeads in consumer products by next year. The tiny plastic particles are turning up in the ocean and in fresh water, like the Great Lakes. They're ingested by marine creatures, creating a huge hazard.

CURWOOD: But haven’t a lot of companies voluntarily promised to stop using microbeads?

Tasmanian devil populations have been reduced by as much as 80% by a contagious cancer, but the discovery of populations with genetic resistance to the disease brings new hope for the species. (Photo: KeresH, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

DYKSTRA: Yeah, including Johnson & Johnson, who makes facial scrubs and body washes, and Procter & Gamble, who among other things makes Crest toothpaste, which for now still has microbeads in some brands but not Triclosan.

CURWOOD: Well that makes for some strong arguments for reading the ingredients before you buy. So you said you had three Peter, what’s the third one?

DYKSTRA: Oxybenzone is a common ingredient in some sunscreens. University of Hawaii researchers say it also stresses coral larvae – one more factor in the alarming decline in coral reefs. They say that on the island of Maui alone, enough oxybenzone washes off swimmers to fill a 55 gallon drum every day. So, state legislators are considering a ban of sunscreens that use oxybenzone.

CURWOOD: So no sunscreens at all on the sunny beaches of Hawaii?

DYKSTRA: No, there are alternatives that don't contain oxybenzone, said to be just as effective, that use zinc oxide or titanium oxide as the active ingredient.

CURWOOD: So what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: There's some hope for an iconic, exotic animal threatened with extinction. Tasmanian devils have been blitzed by an epidemic of infectious cancer that they catch from each other by biting and that’s claimed as much as eighty percent of their population in recent years.

CURWOOD: Now over here, most people know the Tasmanian devil as Taz, the cartoon character.

DYKSTRA: Right, and Taz in the Warner Brothers cartoon is faithful to the real Tasmanian devils, but only to a point. The real ones have outsized heads and a ferocious growl and bite when feeding, but unlike the cartoons they usually walk on all fours and don’t whirl around like a tornado. They are also said to stink to high heaven.

CURWOOD: So what’s the good news for this animal that I'm not sure I want to really meet in person?

DYKSTRA: Researchers have found three separate devil populations whose genomes show an extra resistance to cancer, which shows up in the form of smothering facial tumors. It’s hoped that these populations can survive the cancer epidemic and keep the Tasmanian devil alive in the wild and not just in cartoons.

The original Piggly Wiggly store in Memphis, Tennessee, photographed in 1918 (Photo: Clarence Saunders, public domain due to copyright expiration)

CURWOOD: That's an interesting development. Hey, what's the anniversary you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well when we think about ideas that have shaped modern life, there are the obvious ones like electricity, automobiles, the internet and a lot more. But 100 years ago this month, a grocer named Clarence Saunders had an idea that changed the way the vast majority of us get our food. Up until then, the standard in food shopping was that you’d write down a list, hand it to a clerk and the clerk would pick out your food for you. But in September 1916, Saunders opened his store, with the dignified name of “Piggly Wiggly,” in Memphis Tennessee.

CURWOOD: And thus the modern supermarket was born, huh?

DYKSTRA: Right, and this idea let Saunders run his store with fewer clerks.

CURWOOD: So today, some would call him a job-killer.

DYKSTRA: Perhaps, but it also spawned two more ideas – the shopping cart and also the bane of all weight-conscious consumers, impulse buying. Not to mention the first step toward today’s megamarkets, including hundreds of Piggly Wigglys all over the south, where you can get food from nearby farms or all over the world.

CURWOOD: Unless, of course, you live in a food desert with no quality food stores.

DYKSTRA: Right, and you can find those in just about any American city, too.

CURWOOD: Indeed, you can. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter and talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: Thanks, Steve

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website, loe.org.

DYKSTRA: That's all, folks!

Related links:

- ABC: “Oxybenzone in sunscreen is damaging coral reefs”

- STAT News: “FDA bans antibacterial soaps containing triclosan”

- BBC: “Plastic microbeads to be banned by 2017, UK government pledges”

- New York Times: “New Hope for Tasmanian Devils in Fight Against Contagious Cancer”

- About Piggly Wiggly

- See pictures of the original Piggly Wiggly

[MUSIC: Warner Bros. Studio Orchestra, “Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies Opening Theme,” Looney Tunes: Golden Collection Volume 4, Carl Stalling, Warner Bros]

Avian Malaria Flies North

The oldest known loon in the Northeastern U.S. is referred to as the Sweat’s Meadow 1993 female, for the year she was banded. She’s probably about 30 years old and has hatched 20 chicks and fledged 11. (Photo: Derrick Jackson)

CURWOOD: With global warming, mosquitoes and other insects and pests that can carry diseases are making their way into places that used to be too cold for them. And while we think of mosquitoes carrying human diseases including Zika, West Nile and Dengue Fever further North, as commentator Derrick Jackson notes, birds are also at risk.

JACKSON: Combine the most iconic bird of the North Woods with one of the oldest tropical diseases and what do you have? A New Hampshire common loon, dead from avian malaria.

The Sweat’s Meadow female brings food to her chicks (Photo: Derrick Jackson)

It was the first such loon death in the world, confirmed by wildlife biologists at several institutions. Here’s how it happened. Campers on a remote site in the Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge, thirty miles from the Canadian border, spotted a floating loon carcass and waved down a patrol boat. A refuge biologist and intern collected the carcass, chilled it and drove it to the Loon Preservation Committee, which then took it to the University of New Hampshire for analysis -- all by the next day.

Malaria is difficult to confirm as a cause of death in a decomposed bird. But this carcass was fresh and the researchers found the disease in its brain, liver, heart and lungs. Malaria kills birds with no evolved resistance quickly, so the researchers were sure the loon was infected by a carrier mosquito at Umbagog. There’s other evidence that avian malaria is flying northward with global warming. It has been confirmed among Arctic birds by researchers at San Francisco State University.

Loons are among the world’s most ancient birds, pictured on Canadian coins, and they’ve rebounded with conservation efforts, though they remain far below historic levels in New England. They’ve weathered many human assaults, from mercury in acid rain to lead fishermen’s sinkers. This very same Umbagog is home to the Northeast’s oldest-known loon, called Sweat Meadows 1993, for the year and place she was banded. Over the years, she has hatched at least 20 chicks, with 11 surviving predation by eagles, gulls and snapping turtles. Her current mate is 22 years old.

Both avian malaria and the type of malaria that affects humans are mosquito-borne, but are carried by different mosquito species. (Photo: CDC Global, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

These old birds represent a triumph of environmental recovery, yet the loon dead from malaria is as haunting as its eerie wails in the middle of the night. It might just have been an unlucky, solitary bird. But it also may be a sentinel warning us that climate change is eroding the distinction between tropical jungle and boreal forest.

CURWOOD: That’s commentator and bird lover, Derrick Jackson.

Related links:

- Read Derrick Jackson’s Boston Globe article on the loon’s death from malaria

- About the Common Loon, from Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge

- Journal article: “First Evidence and Predictions of Plasmodium Transmission in Alaskan Bird Populations”

- Burlington Free Press: “Malaria sleuth at UVM tracks parasite to deer”

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE® THEME]

BirdNote: Common Mergansers

A male Common Merganser. (Photo: Gregg Thompson)

BirdNote®

Common Mergansers Parallel Loons

CURWOOD: We’re up in the northlands with water and the birds that live on it for BirdNote® today. And as Michael Stein explains, sometimes birds are not what they seem.

[Common Merganser calling - file from Lang Elliott, musicofnature.com]

STEIN: On a northern lake surrounded by dense evergreens, a large water bird rests on the surface. Its long, slim body – more than two feet of it – appears mostly white, the back black, the head a deep green. And all of it glistens. The bird dives under, a graceful sliding motion. Then returns to the surface with a fish grasped firmly in its beak.The bird’s shape and behavior spell “loon.”

[Common Loon brief vocalization, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/43039, 0.35-.38]

But this is a male Common Merganser, a very large duck that hunts fish for a living.

[Common Merganser calling, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/61558, 0.14-.17]

The Common Merganser is one of our biggest ducks, about the size of some loons, or even a small goose. Although it’s not closely related to loons, it has evolved a similar overall structure and predatory behavior. But a merganser has a unique feature that a loon lacks: tooth-like serrations along the edge of the bill that help the bird grasp slippery fish.

A female Merganser. (Photo: Gregg Thompson)

Common Mergansers nest in the northern states and Canada. So do loons. But loons nest on the ground, while mergansers nest mostly in tree cavities and rock crevices. Cavities big enough to house a hefty 3½-pound female, plus about a dozen jumbo eggs. I’m Michael Stein.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Common Merganser calls recorded by Lang Elliot, musicofnature.com. Common Loon brief vocalization, 43039 and 61558 recorded by William W. H. Gunn, provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org September 2016 Narrator: Michael Stein

http://birdnote.org/show/common-merganser

CURWOOD: And for photos, paddle on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Listen to this note on the BirdNote website

- More on the Common Merganser

- More BirdNotes about the Common Merganser

[MUSIC: Wendy Rolfe/Deborah DeWolf Emery, “Rachel’s Song,” Images Of Eve, Beth Denisch]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how a smallpox epidemic helped to foment a political and medical revolution in colonial Boston. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Fishtank Ensemble, “Mehum Mato,” Samurai Over Serbia, traditional Serbian/arr.F.Martinez, HoneyBeatzRecords]

The Fever of 1721

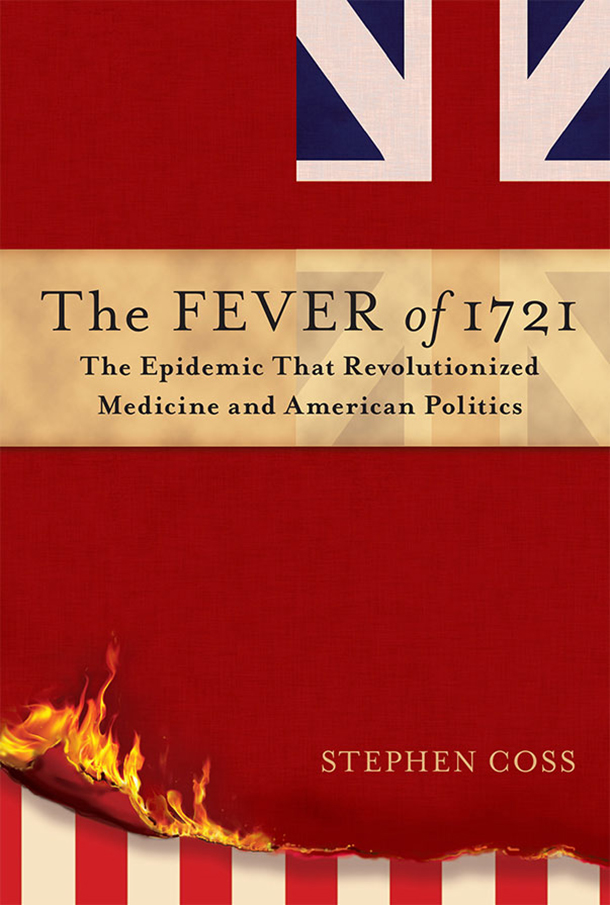

The Fever of 1721 is Stephen Coss’s first book. (Photo: courtesy of Stephen Coss)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Western medicine can be woefully behind the wisdom of ancient civilizations and tribes, as author Stephen Coss reveals in his book about the smallpox epidemic in Boston back in 1721. He tells how the fight in Boston to tap Asian and African understanding of smallpox inoculation also played a major part in fomenting the American Revolution, launched a combative free press along with the career of Ben Franklin, and also advanced science.

Today, with our understanding of infection and hygiene, the idea of squirting pus into an open wound sounds repellant – to say nothing of dangerous. Yet it was this very procedure that saved lives during the severe smallpox outbreak chronicled in “The Fever of 1721”. This swashbuckling tale of how Bostonians finally accepted inoculation also highlights a pirate chasing ship, and the wisdom of Onesimus, a slave owned by Cotton Mather of Salem witch trials infamy. Stephen Coss joins us to now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

COSS: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, where did the idea for this book come from?

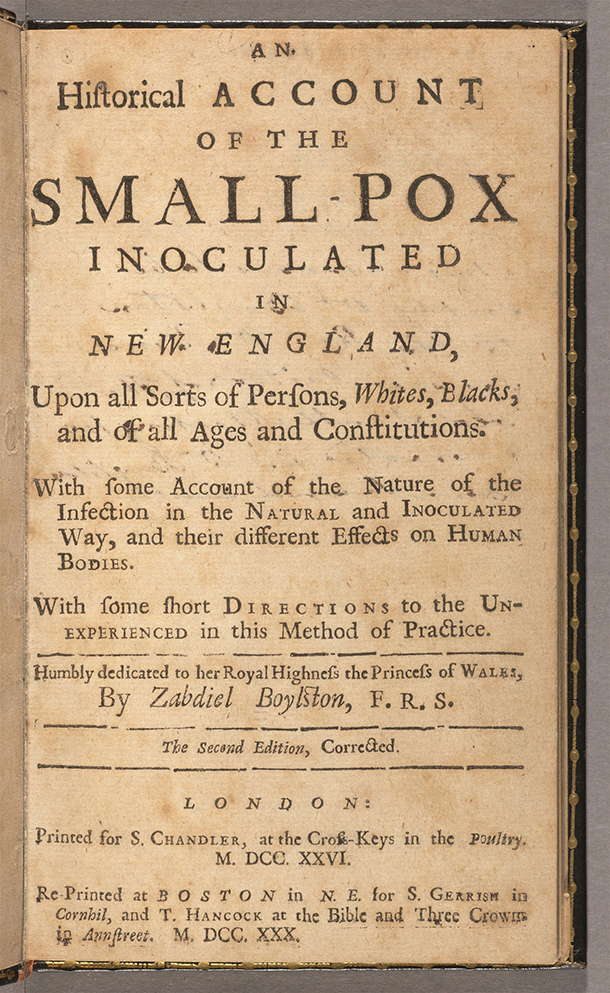

COSS: Well, the original idea came from a desk calendar that was essentially a fact a day calendar from my wife and kids. And as I thumbed through this calendar which I noticed the event I ended up writing about, the June 1721 inoculation experiment in Boston where a doctor named Boylston conducted what turned out to be the first inoculation experiment in western medicine. And I saw from that one little calendar page that it had been suggested by Cotton Mather, whom I had always thought of as the bad guy from Salem, and I had no idea there was any other dimension to him so that got me going.

CURWOOD: So, we've got a number of things are coming together here in your story of 1721. Let's talk about smallpox and the medical history here. And first question actually, what is inoculation?

COSS: That is a very good first question because a lot of people think inoculation and vaccination are the same thing when they're really not. Inoculation preceded vaccination, and inoculation involved taking smallpox pus from someone who was broken out in the disease and implanting it in an incision made in the arm, usually the arm of someone who had never had the disease, and the whole idea was to give the person who was inoculated a mild survivable case of the disease which would then, after they recovered, render them immune to any further infection.

Day 5 of a 30-day watercolor series depicting the progression of a sore from smallpox inoculation, painted by George Kirtland in 1802. (Photo: George Kirtland, Wellcome Images)

CURWOOD: And remind us today of how deadly smallpox was and why this is such an important turning point.

COSS: Yeah, absolutely. Smallpox was until it was finally eradicated, the deadliest disease in the world. When smallpox came to a town like Boston, generally speaking, everyone who hadn't had it and was exposed to it would get it. In terms of those who got it, depending upon the population, it could go anywhere from 30 percent fatalities to ... There are cases with some Native American populations that had never experienced it at all where the fatality rate was approaching 90 percent.

CURWOOD: And I gather it's not a fun way to go.

COSS: No, it was an agonizing way to go. It was, in addition to all the things we associate with being sick in terms of fever, in terms of headache, stomachache, vomiting you had of course these horrendous sores, and the sores could become so thick that they were what would be called confluence smallpox where they all touched each other and created really a mat of sores on the skin.

CURWOOD: One of the things you write in your book is this inoculation process was actually well-known to humans over history, that it had been practiced in Asia and in Africa going way back. Why do you suppose that folks in Asia, parts of Africa knew about this, but it hadn't been introduced to Europe?

COSS: I think a lot of it had to do with the age of the culture, the edge of the civilization. A lot of things originated in the Far East and Europe only got them sort of later on. I think the reason it didn't get communicated or didn't become commonplace in Europe and in America after that, until it did, was simple Western arrogance.

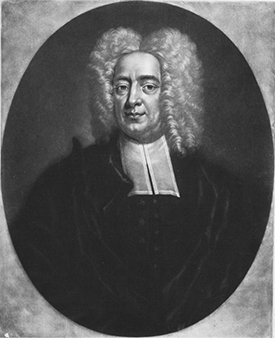

CURWOOD: So Cotton Mather learns this from Onesimus. What exactly happened there? Tell me the story.

COSS: Mather in about 1716 came across what would then be considered a scientific journal article about inoculation being practiced in Constantinople. Not long after that, the way he tells it he was having a conversation with Onesimus who worked in his house as a slave and in the course of that conversation, Mather asked Onesimus about a sort of unusual scar on his arm and Onesimus proceeded to explain that that was really not a big deal where he came from. When smallpox came to the town, inoculations would be done, and he had been inoculated as a very young boy.

Smallpox produced a painful, unsightly rash on the face, arms, and legs of its victims. (Photo: Wellcome Library, London)

CURWOOD: Interesting. So, 1721, Boston has this horrible encounter with smallpox. What set off this particular epidemic?

COSS: Well, Boston ... it's funny Boston got smallpox almost like clockwork, about every 12 years they’d get a new epidemic. In this case, though, it had been almost 20 years since they had gotten smallpox. When smallpox did return in 1721, there were many many more people who were vulnerable to it and it became the worst outbreak that they’d ever had. The way it came into Boston was on board a British warship called HMS Seahorse. Now, Boston did have provisions for quarantine and there's an island in Boston Harbor - still there, a beautiful park now called Spectacle Island. Spectacle Island in 1721 was what was called the pest house and that was the quarantine station. But the British Navy was not obliged to follow the rules, basically, and so a somewhat arrogant captain came in the Boston Harbor realizing that he had picked up smallpox in Barbados where a very bad epidemic was raging. He came in and hid the fact that his ship was infected and slowly but surely it began to spread in the town.

CURWOOD: At the same time, of course, there's a lot of tension in Boston with the British occupiers so the crown is really being challenged for control of this particular colony. So how does this fever come together with the American Revolution as you postulate in your book?

A British ship carried smallpox into Boston (seen in the distance) in 1721. (Photo: Joseph F. W. Des Barres, Boston, as seen between Castle Williams and Governor’s Is- land, distant 4 miles . . . (Detail). Map image courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal

Map Center at the Boston Public Library).

COSS: Well, there are several ways. I mean, the most direct connection I think is that the smallpox epidemic ended up becoming a leverage point or a point of contention between the royal Governor, who represented Britain obviously, and the elected House of Representatives which had been really flexing its muscle. This had been going on for several years and their relationship was quite contentious and it was quite dysfunctional, and in fact, one of the reasons smallpox got out of control is that there was so much dysfunction at the political level that they were unable to work together to nip it in the bud, so to speak.

CURWOOD: And then this guy Cotton Mather, who has this horrible reputation from the Salem witch trials, starts talking about dealing with the smallpox epidemic with, well, it doesn't sound exactly like the nicest thing to do: to slice your skin and drop in pus from somebody who’s got smallpox.

COSS: Well, no one thought it was a really good idea at first except that Zabdiel Boylston, the one doctor who matter convinced to try the experiment, and the reason Boylston tried it, by the way, was because he had grown up outside of Boston. His father was a doctor who had traveled a lot to the countryside and had a lot of interaction with Native Americans, so he was predisposed towards listening to ideas that came away from the mainstream. It was so counterintuitive to give somebody a disease to save them from a disease. The outrage was just enormous. Both Boylston and Mather, their lives were threatened. In fact, at one point, someone did throw a bomb through Cotton Mather's bedroom window. So it was very volatile.

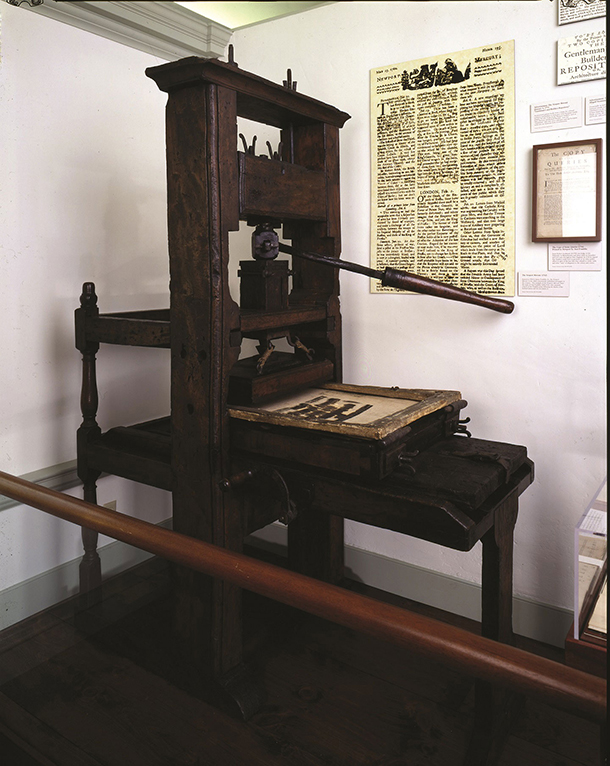

Benjamin Franklin helped his brother James print The New-England Courant using this printing press. (Photo: Newport Historical Society)

CURWOOD: And you also write in your book, Steven, that in this horrific scene emerges the first really free American press. How does this connect to the outbreak of smallpox and the unpopularity of the colonial governor?

COSS: Well, what happened was there was a young man named James Franklin and that last name will be familiar to you and to everybody else who is listening because he was the older brother of Benjamin Franklin. Well, in 1721, James Franklin started a newspaper called the New England Courant and that would become the first independent newspaper in America which meant that he published it without asking permission or trying to please the royal authority with what he printed. When smallpox came along he decided, “Aha I've got this wedge issue, I got this controversial thing. I can jump on this by being anti-inoculation actually.” He jumped on the popular side of of the debate and then once having done that he did turn it to things that he was really interested in, which was politics and social issues and humor, and that's what he did.

CURWOOD: So what you're telling me is the birth of the free press in America is tied to an entrepreneur who went into business to prey on the fears of the public.

COSS: In essence I am. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: This newspaper that got started by James Franklin. What was the flavor and tenor of that, and what analogies to today might you make about this publication?

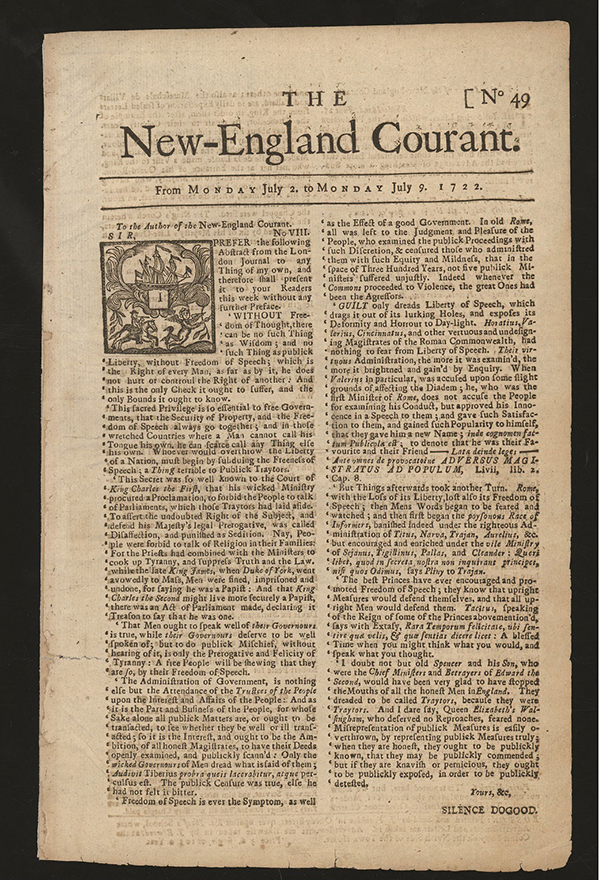

A page from the New-England Courant (Photo: Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society)

COSS: It was interesting because as I said it covered a lot of serious ground. Before the New England Current, nobody would ever dare report an election result, believe it or not. The government was the only one who could decide whether people should know who won the election for representative to the House, the Massachusetts House. It was also very racy and it was also funny. In fact, I think you can draw a straight line from things like The Daily Show or the Colbert Report or The Onion. Benjamin Franklin made his debut as a writer in this newspaper as Silence Dogood, a name which many people might know. And Silence Dogood wrote kind of humorous articles that poked fun at Harvard, that poked fun at prostitution, that poked fun at drinking, and, mind you this is in puritan Boston in 1721. These are not people who are generally known to have had a great sense of humor about anything.

CURWOOD: At the same time in the same town you have a Ben Franklin working on this newspaper with his older brother. How did that work out?

In 1724 Zabdiel Boylston published his account of smallpox inoculation in New England. (Photo: EC7.B6988.B730e, Houghton Library, Harvard University)

COSS: Yeah, I say, only half kidding, that in 1721 everything Ben Franklin ever really needed to know he learned, that year, because the experience of working with his brother in that town at that period with those challenges really changed the way he thought about politics, about the press and freedom of the press. Obviously he saw what his brother was doing. He saw Boylston conduct this experiment which was important for Franklin in two ways. One was it was the first real experiment that Benjamin Franklin the great experimenter had ever witnessed firsthand and it also made Boylston a hero, and Boylston like Franklin was a man of humble origins. He didn't have a Harvard College education like most of the other doctors in town. He didn't come from a prominent family or a wealthy family, and I think Ben Franklin walked away from this experience realizing the potential of his own life in a lot of different ways.

CURWOOD: So, now that we've told this part of the story, let's bring this together. How does smallpox and the media come to, as you put forward in your book, really in some respects start the American Revolution, start that ball rolling?

COSS: Well, there are really two strains there. I think there's the role that smallpox had in exacerbating what was already a really interesting political rebellion by a man named Elisha Cooke who I consider sort of our founding grandfather. He was the guy behind all of the political opposition to Great Britain. When smallpox came along and became sort of a wedge issue for the politicians, what it did was really amp up that fever, that political fever. So that's one way for sure, and Elisha Cooke's party which would become known as the Boston Caucus actually came to fruition around 1721 and started a few years earlier, and from 1721 on to 1776, it was the mechanism and the infrastructure for the American revolution. Meanwhile, you’ve got James Franklin and the whole freedom of the press thing and you've got someone for the first time in American history actually saying that the press ought to have a right to criticize the government.

Cotton Mather was a leading Boston minister in the early 1700s and learned of the practice of inoculation from his slave, Onesimus. (Photo: Peter Pelham, Cotton Mather. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society)

CURWOOD: Let's digress for a moment from 1721 to 1776 and smallpox again and the role that Ben Franklin played at that time.

COSS: Yes sure, sure. Well, Ben Franklin, largely because of this went, as we all know, to Philadelphia, and in Philadelphia he became a huge proponent of inoculation, arguably the number one proponent of inoculation in all of the colonies, and because of that Philadelphia became the center of inoculation. Jefferson went there to be inoculated. Many people were inoculated there. Benjamin Franklin, because he believed in inoculation, also kind of nurtured a new generation of physicians who were pro-inoculation and in fact both of the men who advised George Washington, once he became Commander in Chief of the Army, strongly pro-inoculation, and in 1777 George Washington made the really daring decision to have his entire army inoculated. A lot of historians believe that maybe the greatest thing Washington ever did as General in the revolution was inoculate his army.

CURWOOD: One of the interesting reflections that I came away from your book with, Steven, is a sense of déjà vu in the current climate discussion, the inability of the policymakers to really deal with it. There are many things about this and in fact really climate change could be seen as a public health issue. How crazy am I to look as that as an analogy?

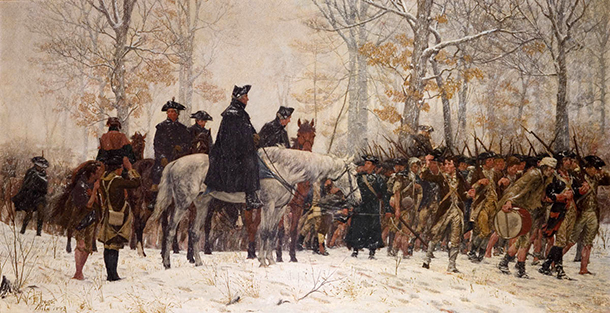

President George Washington’s decision to inoculate the Continental Army very likely helped the American colonies win the Revolutionary War. (Photo: painting by William B. T. Trego, “The March to Valley Forge,” public domain)

COSS: I don't think that's crazy at all. I hadn't thought of that but I see a lot of similarities. You know, I think what we saw in Boston that ties to, not only today but all through history since and probably before, is a sense of the pull between public health and money to be honest with you. I mean, it's interesting. In 1721 Boston with the third busiest seaport in the entire British Empire, so the idea of a smallpox epidemic was fearsome, not only because of the health implications, but also the financial implications. Smallpox comes to Boston, Boston gets embargoed by its trading partners and the economy goes down the drain, and I think the officials in Boston had an opportunity to act early on in a way that might've minimized the spread of the smallpox and ultimately prevented an embargo which did happen eventually. So the worst expectation of the leaders in Boston relative to an embargo ended up happening, and sometimes I think that in a lot of cases including climate change, including some other contagious diseases for that matter, you see that it's not so much that we don't have the knowledge or the technology to stop something. We seem to lack the political will because of issues that have to do with profit.

Stephen Coss.(Photo: courtesy of Stephen Coss)

CURWOOD: Steven Coss's book is called "The Fever of 1721: The Epidemic That Revolutionized Medicine and American Politics". Thanks so much for setting the time today, Steven.

COSS: You're welcome Steve, thank you.

[MUSIC: Dudu Maia, “Didi E Gonzaga,” Dudu Maia, Pixinguinha/Bonodito Lacerda, Dudu Maia Records]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, how farming helps veterans deal with Post Traumatic Stress disorder.

JACKSON: Animals don’t care about your bad day. They’re going to come up and they’re like, ‘I want you to pet me.’ You’re like, ‘OK, but I’m feeling really mad right now, but man, they don’t know the amazing stuff they do for our vets who come through.

CURWOOD: The power of goat and pig therapy for vets. That’s next time, on Living on Earth.

Related links:

- Harvard University Science in the News: “The Fight Over Inoculation During the 1721 Boston Smallpox Epidemic”

- Stephen Coss’s author website

- The New-England Courant and the Smallpox Inoculation Controversy

- Boston Globe: “How an African slave helped Boston fight smallpox”

- George Washington and the First Mass Military Inoculation

- About the Smallpox Eradication Program

[MUSIC: Dudu Maia, “”1x0,” Dudu Maia, Pixinguinha/Bonodito Lacerda, Dudu Maia Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Special thanks this week to Democracy Now. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe, Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on Facebook - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth