June 14, 2019

Air Date: June 14, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Sobering Climate Risks

View the page for this story

If carbon emissions keep going up until 2030 it will be too late to avoid a ‘hot house’ Earth with a billion climate refugees starting in 2050, according to the Australia-based Breakthrough National Centre for Climate Restoration. These researchers warn the climate is changing faster than politicians and the public are responding, and say interventions on a scale never before seen during peacetime are needed right now. Host Steve Curwood talks with David Spratt, Research Director at the Breakthrough National Centre. (11:43)

Note on Emerging Science: Hot Potato Blues

/ Joseph WintersView the page for this story

Potatoes are a staple food for populations around the world, including the developing countries Bolivia, Rwanda, and Kyrgyzstan. But when the temperature rises over 70 degrees Fahrenheit, potatoes produce vastly fewer, and less nutritious, tubers. New research has uncovered why hot potatoes are so unhappy, and even discovered a way to grow more nutritious potatoes in hotter weather. Living on Earth’s Joseph Winters explains in this week’s note on emerging science. (02:47)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood first take a look at some controversial suggestions from the current Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo about how people can cope with mounting climate impacts. Then, the two discuss the Democratic National Committee, which has declined requests from candidates and activists alike to feature a climate change-focused debate during the Democratic Presidential primary season. Finally, the pair take a look back in history to the groundbreaking paper that linked chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, to ozone layer destruction. (03:57)

Exploring the Parks: Cactus and Snow in the Desert Sky Islands

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Coronado National Forest, north of Tucson, Arizona is the latest subject of Living on Earth’s occasional series on America’s public lands. There’s plenty of heat and cacti, of course, but also many species ordinarily found far north of the desert Southwest. With a local biologist as her guide, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on the remarkably diverse biomes of Arizona’s Sky Islands. (11:01)

BirdNote®: Ponderosa Pine Savanna

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

The unique ecology of the ponderosa pine savanna, which covers much of the desert Southwest, has been shaped in large part by fire. BirdNote’s Mary McCann has more about the birds that call this landscape home. (01:54)

Horizon by Barry Lopez

View the page for this story

The author of National Book Award-winning Arctic Dreams took around 30 years to write his latest book, Horizon. It’s a sweeping account of his lifetime of traveling the world and seeking the perspectives of diverse cultures. In his quest to understand the human race’s current predicament, Mr. Lopez asks: “Who is our navigator?” in this time of climate change and pervasive inequality. Barry Lopez speaks with Host Steve Curwood about the importance of acknowledging “the horrors” of our past and present, and striving towards a more humane and hopeful future. (15:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Barry Lopez, David Spratt

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann, Joseph Winters

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

An economic and social look ahead for the next 30 years sees some dreadful faces of climate change.

SOBEL: The one that truly terrifies me is the billion people displaced from the tropics, and it’s hard to imagine our current states, democratic or otherwise, being able to handle that, and so you can easily imagine wars starting over it, and that’s where I think the really scary stuff starts.

CURWOOD: Also, the Sky Islands of Arizona.

AVILA: When we are at 110 degrees down in Tucson, you can come up here and be at a nice 70 or 75 degrees. And so yeah, the sky islands are this amazing mix of desert and mountains and little treasures. You might go into one of these canyons and find a little creek or something and see something that you didn't expect to see.

CURWOOD: It’s part of our tour of America’s public lands. That and more this week on Living on Earth – stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Sobering Climate Risks

According to the Breakthrough National Centre for Climate Restoration’s paper, Existential Climate-Related Security Risk, scientists and politicians have focused too much on middle-of-the-road climate scenarios. If the planet warms by 3 degrees Centigrade from pre-industrial averages – which is the path that the current Paris Climate Agreement has us on – the planet could face a climate catastrophe. To avoid the worst consequences, David Spratt calls for immediate action and total decarbonization, or close to it, by 2030. (Photo: Daniel Lerps, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

So if the nations of the world stand by their present commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement, which allows global warming gases to increase until 2030, we are likely setting ourselves up for catastrophe. That’s according to researchers at the Australian Breakthrough National Centre for Climate Restoration, who warn political systems are moving much slower than the climate is changing. Their paper says the present targets would lead to 3 degrees Centigrade, or more, warming by 2050, which could create a “hothouse Earth,” making large regions of the planet uninhabitable, so there is no time left for incremental policy changes to decarbonize our economy. The researchers call for immediate, unprecedented intervention on a scale never seen before during peacetime, and warn that human civilization itself hangs in the balance.

Here to explain is David Spratt, research director for the group, on the line from Melbourne, Australia. Hi, David, welcome to Living on Earth.

SPRATT: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: In your view, how well is the planet doing, are the governments around the planet doing, in limiting emissions such that we won't hit a three degree or higher increase by the year 2050?

SPRATT: Well, the answer is not very well at all. The commitments that countries have made so far at Paris and subsequently put us on a path for at least three degrees of warming.

CURWOOD: So how soon, then, do we need to start decreasing emissions to avoid that scenario?

SPRATT: The faster we decrease emissions, the lower the amount of future rises in the system. We have leading scientists like James Hansen saying that even two degrees is a recipe for disaster. We have new papers saying that if we get to two degrees, we may have a “hothouse Earth” consequence where the system keeps on going of its own accord. We really have to do this in 10 years, we really have to mobilize to rebuild our industrial system, to rebuild our energy system in 10 years. The sooner we do it, the more terribly dangerous warming we will avoid.

CURWOOD: And when you say we have 10 years, that is to begin lowering emissions or to get to really zero emissions, effectively?

SPRATT: I think to get to zero. The hotter it gets, the worse the impacts are. There are not moments where we step off the cliff, these impacts ramp up with the emissions. We are already in dangerous climate change now. We, now at the present level of warming, about 1.1 degrees, have created the conditions for the loss of the world's coral reefs, we have scientists telling us that in West Antarctica, the system is already primed for several meters of sea level rise. And you know what one meter of sea level rise will do to Florida, for example. Climate change is already dangerous.

CURWOOD: Now, what kinds of things, in terms of the natural world, are you predicting we'll see if we get to the three degrees Celsius by the middle of the century?

SPRATT: So we've looked at three degrees and said, what would that mean based on the peer-reviewed science? And we know from that science that, while we might have a sea level rise of half a meter by 2050, there will be many meters in the system because ice melts slowly, but once it starts, it doesn't stop very easily. We know that we will have lethal heat conditions, particularly in the tropical zone, particularly in Asia and West Asia, where it would simply be too hot for months a year for people to live without air conditioning. We will have changes in weather systems, in monsoons. We've seen the destabilization of the jet stream being incredible, hot and cold. We will be looking at a loss of perhaps a third of the ice from the Himalayas, and it is the melting of that ice that drives the water flow through the seven great rivers of Asia. We are looking at the subtropical zone drying out and desert-ifying. So there's peer-reviewed science saying the Sahara will jump the Mediterranean, into southern Spain, Italy and Greece. In the end, we're talking about lands and places where life will simply become unviable because it's too hot, too dry, or there's not enough water. And in the end, this is all about whether we have the land, the food, and the water for people to survive.

CURWOOD: Talk to me in some detail about your scenario, about the effect on human civilization. What happens to poorer countries? What happens in terms of displacement? What happens to food and what happens in terms of conflict, perhaps?

Climate change has already played a part in displacing millions of Syrians, says David Spratt, and by 2050 rising global temperatures and sea levels could force as many as a billion people to flee or relocate. (Photo: Ggia, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

SPRATT: If we look, for example, at food, we can see a number of things intersecting here. As it gets hotter, some lands will desert-ify. I mean, for example, we have seen in Syria, a civil war that has internally and externally displaced 11 million people out of a population of 17 million, in part driven by the desertification of eastern Syria, a record-breaking drought. We can look across the Sahel, in Mali, in Darfur, for similar examples. So we have desertification. As it gets hotter, crop yields will decline. We already have the news recently of catastrophic declining in insect populations around the world, perhaps a loss of two and a half percent of the world's insect population each year. I mean, these are pollinators of our crops. These things cycle together into a food crisis. And when you have food and water crises, then you have social conflict. The United Nations has said that in another 30 years by 2050, we could have a billion people who will have to fight or flee because of land, water and food issues.

CURWOOD: So in your view, is this an emergency? Is this a crisis? Is this Armageddon?

SPRATT: No. This is not Armageddon, I don't think we should be doomerist. I think throwing up your hands and saying it's too late is really counterproductive. I think those tendencies are really disturbing, particularly for young people. There's been some misreporting saying we’ll all be dead in 11 years—that is not correct. The impacts ramp up with temperature. We have the climate impacts, we also have some other sustainability crises, in the sense that we are using more of the earth's resources each year than we can sustainably do. So there are multiple issues, there is the degradation of our oceans. So I think there are a number of issues all swirling together, and they will spiral up. I think we now have to say that this is the greatest threat to human civilization, and the greatest threat that human civilization has ever faced. The problem is that the status quo is a suicide.

CURWOOD: So how long do we have to act? The things you're projecting sound pretty dire to me.

SPRATT: How long did the United States have to act after Pearl Harbor? There are circumstances in which you have to act as fast as you possibly can. This threat may become overwhelming, we have to make this the number one priority of the society and throw everything at it. And that's where we are with climate change. This is not just another issue. This is the issue. If we don't solve this issue, then all the other things we care about will simply become irrelevant because we will be in such a state of international social crisis. Australia's leading climate scientist who was an advisor to our government for a number of years, Professor Will Steffen, he said we need something like a wartime mobilization to roll out renewable energy dramatically. So I think that's the idea we have to catch on to. This has got to be the primary target of economics and politics and government.

CURWOOD: So you're not talking about just small changes or incremental things, but you're saying that—

SPRATT: I'm talking about the day after Pearl Harbor. I’m saying, okay, we now realize we have a really big problem. How quickly can we act? I mean, can we call in, as happened at that time, the car companies and say, we have news for you, you have produced the last civilian car till the war is over. Now you're going to produce the things we need for this effort. And that period of the war was a period of incredible economic expansion in the United States. All available resources were thrown at the effort, and it was a period of high employment. It was not unprofitable for those companies, either. And it set up the base of the post-war boom. So these rapid mobilizations, these rapid transitions, we saw it in Japan, I mean, what used to be called the Japanese miracle, we see it in China, where the Chinese economy was transformed in 20 years, can be done if there is leadership.

CURWOOD: So how does one solve this problem? We do not have world government. Every nation is its own sovereign state. And there's a wide variety of opinions, and sometimes sovereign states produce Hitlers. And yet for the civilization to survive on this globe, virtually every nation—certainly the preponderance of nations that emit significant amounts of greenhouse gases—they've got to get aboard this.

SPRATT: Yes, I think we have an international policy-making system which has really produced some lowest common denominator outcomes in that, at the international conferences, everybody has to sign off on a deal, including Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi and Russia and so on. So, it's very easy to get the lowest common denominator actions. I think leadership may come from those countries who are more willing to act actually banding together and leading by example. Am I hopeful? Look, I hope so. But it requires leaders to lead and in the political class, we do not see a lot of that at the moment. Everybody is sitting and waiting. There aren't the Churchills, there aren’t the Roosevelts saying... This is the issue, if political leaders lead, the populations will follow. That's what's missing: genuine leadership.

David Spratt calls for massive, rapid climate intervention, comparing the effort needed to the United States’ mobilization after the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor. (Photo: U.S. Navy, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: David Spratt, the scenarios that you outline are so dire. To what extent do you think that the production of fossil fuel should be a matter of criminal justice?

SPRATT: I think there has been predatory delay by the fossil fuel lobby. There is now evidence, documents in the public domain, that the major fossil fuel producers have known the consequences of climate change since at least the mid-1980s. Are there criminal sanctions against that? That depends on the jurisdiction. But certainly the morality of continuing to produce products that you know will lead to the breakdown of human civilization seems a crime of the highest order to me.

CURWOOD: David Spratt is Research Director for the Breakthrough National Centre for Climate Restoration in Melbourne, Australia and co-author of Climate Code Red: The Case for Emergency Action. Thanks so much for your time today.

SPRATT: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- CNN | “Climate Change Could Pose 'Existential Threat' by 2050: Report”

- USA Today | “End Of Civilization: Climate Change Apocalypse Could Start by 2050 if We Don't Act, Report Warns”

- Breakthrough Center Policy Paper: Existential clmate-related security risk: A scenario approach

[MUSIC: Hubert Laws, “It’s So Crazy” on My Time Will Come, by William Jeffrey & Hubert Laws, MusicMasters Jazz]

CURWOOD: Coming up – a technological solution to help feed people on our warming planet. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Pinetop Perkins with Ann Rabson, “Careless Love” on Ladies Man, by Ledbetter, M. C. Records]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Just ahead, the remarkable Sky Islands of the desert Southwest, but first, this note on emerging science from Joseph Winters.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Note on Emerging Science: Hot Potato Blues

Researchers at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg have found a way to make potatoes produce tubers in abnormally-hot lab conditions. Their next project is to see if they can repeat their results in the field. (Photo: Øyvind Holmstad, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

WINTERS: Global warming is like a double-whammy for agriculture. First, there’s the extra carbon dioxide. Although plants need to take in CO2 for photosynthesis, too much carbon dioxide can actually make plants less nutritious. They grow bigger, tougher leaves, but the vitamins, minerals, and proteins are diluted.

Then there’s the warming itself: not all plants thrive when you turn up the thermostat, even just a few degrees. One such example is the humble potato, whose growth declines when temperatures climb over 70 degrees Fahrenheit. This could be a big problem for a warming world. In many developing countries—places like Rwanda, Kyrgyzstan, and Bolivia—tubers like the potato underpin food security.

The problem with hot potato plants is that high temperatures somehow stop potatoes from forming underground tubers—a process called tuberization. In hot weather, potato plants sprout more green shoots and leaves, but barely produce any spuds. And the few tubers that do sprout have less starch, fewer nutrients, and are quick to rot.

This May, researchers at Friedrich-Alexander-Universitat Erlangen-Nurnberg, a German research university, finally found out why. They had already known about a protein called SELF-PRUNING 6A, which tells potato plants to make tubers when the temperature is cool enough. But what they discovered was that a small bit of genetic code—a specific RNA chain—could turn off SELF-PRUNING 6A when the weather got too warm. Under milder weather, the RNA chain simply lay dormant in the potato plant.

Potatoes produce bigger leaves, but fewer tubers, at temperatures above 70 degrees Fahrenheit. This could be a problem for a warming world, since the potato is a staple crop for many populations, especially in developing countries including Bolivia and Kyrgyzstan. (Photo: Maksym Kozlenko, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The researchers' experiment, which was led by the university’s biochemistry chair Dr. Uwe Sonnewald, went on to try growing potato plants in which they deactivated the tuber-blocking RNA. They placed potted potatoes in a super-hot greenhouse and, sure enough, the potatoes produced healthy tubers.

It remains to be seen whether deactivating the small RNA will still produce healthy spuds in the field; this is Dr. Sonnewald’s next research objective. It’s another issue entirely whether consumers will be willing to accept the genetically-modified hot potato, citing unknown side effects on health and ecology. For the time being, the researchers are hopeful that even in a warming world, there will still be an option for growing our favorite starchy vegetable. We may have to say goodbye to a cooler, pre-industrial climate, but we may not have to part with home fries and tater tots. At least, not just yet.

That’s it for this week’s note on emerging science, I’m Joseph Winters.

Related links:

- EurekAlert | “How potatoes could become sun worshippers”

- Read the study here

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Beyond the Headlines

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has recently made some controversial statements about the warming planet – such as how melting sea ice could open up new trade passages, or how those threatened by climate disasters in their homes could move to new places to escape. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time now to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He's an editor at Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what's going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. We're going to start with a few pearls of wisdom from Washington, DC. Specifically Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who recently said climate change, as a longstanding threat, can be dealt with, because modern societies can simply adapt to a changing environment by moving people out of harm's way. If you live in a place that's inundated by sea level rise, you move. If you can't grow your crops anymore, you move. If you're out of drinking water because your glaciers have melted, you move.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, we just heard, earlier in the show, scientists really concerned of how volatile it will be to have literally a billion people around the world moving to avoid climate change. Hm.

DYKSTRA: And not only is that one part of the cataclysm we may face, Pompeo also recently admitted that climate change was happening. He did so by saying the melting Arctic was just a nifty way to open up new trade routes between Asia and the West. It's a little like saying that burning your house down was a nifty way to take the chill out of a cold winter night

Tom Perez, current chairman of the Democratic National Committee, has denied calls for a climate-focused presidential primary debate from candidates and activists alike. (Photo: Lonnie Tague, United States Department of Justice, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Indeed. Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, you might think with all this public concern rising over climate change - we hear about things just in the past few weeks, like 100 degrees in San Francisco in early June, 122 Fahrenheit in parts of India - that the Democrats, with their school bus full of 2020 challengers, and up to a dozen primary debates, that they might peel off one of those dozen debates and have a focus discussion on climate change. But no.

CURWOOD: Well, that's interesting, because back in 2008, the League of Conservation Voters sponsored a debate on environment and climate that actually I moderated. And we talked plenty about climate then.

DYKSTRA: Oh, yeah. The Democratic National Committee Chairman Tom Perez - we tried to contact the DNC, I haven't heard back from them - but in separate statements, Perez said that if he made a separate debate about climate change, he'd have to do that for all the separate issues too. And for candidates like Jay Inslee, who qualifies for the debates, he's been told that he would be blacklisted if he or any of the other candidates participated in any non-DNC debates, like the one that you moderated back in 2008.

CURWOOD: Peter, by the way, when was the last time that climate came into the presidential debates anyway?

DYKSTRA: The only time in a presidential debate between the Republican nominee and the Democratic nominee, were asked a question on climate change was 11 years ago. In 2008, Bob Schieffer of CBS was the moderator. He asked Senator Barack Obama and Senator John McCain about climate change, and they mostly danced around the issue in their answers.

Rowland Hall at the University of California, Irvine was named after Sherwood Rowland, who won the Nobel Prize in 1995 for his work with Mario Molina in linking chlorofluorocarbons to the destruction of the ozone layer. (Photo: David Eppstein, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Hey, Peter, what do you have from the annals of history for us today?

DYKSTRA: We'll go back 45 years to June 1974. Two professors at the University of California Irvine, Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina, authored a paper linking chlorofluorocarbons to ozone layer destruction. They shouldered years of flack from industry, particularly DuPont, from the big CFC makers, but their work was vindicated. We came to not only find out that we had a huge problem with the ozone layer, but we took steps in a bipartisan way, in a global way, to begin to solve the problem. Sherwood Roland, Mario Molina, and a Dutch scientist named Paul Crutzen ended up winning the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work.

CURWOOD: Indeed, truth in science is the long-term truth, isn't it, Peter?

DYKSTRA: It is.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- CNN | “Pompeo Downplays Climate Change, Suggests ‘People Move to Different Places’”

- Mashable | “DNC Swiftly Kills the Idea of a Climate Change Debate”

- The Hill | “DNC Chair Says 2020 Climate Change Debate Is ‘Not Practical’ After Being Confronted by Activists”

- Los Angeles Times | “Ozone Warning: He Sounded Alarm, Paid Heavy Price”

- The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995

[MUSIC: Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, "This Land is Your Land" on Naturally, Daptone Recording Co]

Exploring the Parks: Cactus and Snow in the Desert Sky Islands

Coronado National Forest has an area of nearly 2 million acres spread throughout southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, including the Sky Islands. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: More than 50 percent of Arizona is actually public land, a tapestry of state and federal land, including national parks and forests. That makes it an excellent destination for summer travels. I know what you may be thinking…. Arizona in summer time? No, thanks! Well, for this installment in our occasional series on public lands, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb visited the Coronado National Forest, north of Tucson and found the forest there is literally full of cool surprises. She went on a hike and drove up Mount Lemmon, roughly 80 miles north of the US border with Mexico. It’s a popular destination for locals and tourists alike.

[SFX CAR PASSES]

BASCOMB: I’m standing on the side of the road at the base of Mount Lemmon. It’s sunny and a pleasant 75 degrees. Sharp grasses and spiny succulents with bright yellow and pink flowers blanket the parched desert ground. I’m here with wildlife biologist Sergio Avila.

AVILA: We can see Sonoran desert plants and animals. We can hear right now some Cardinals, we can hear some Curve-billed thrashers, we can hear some mockingbirds.

BASCOMB: Sergio is outdoors coordinator for Sierra Club in the Southwest Region. Originally from Mexico, Sergio has thick black hair pulled back in a low ponytail.

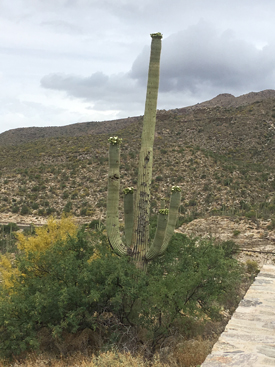

AVILA: We are looking at the saguaros, which is the iconic, kind of descriptive plant of the Sonoran Desert.

BASCOMB: These saguaro cactuses stand sentry some 60 feet tall with large white flowers on each of their massive arms reaching upwards. I think the inventors of those cactus-shaped margarita glasses must have had the saguaro in mind.

The Saguaro cactus is an icon of the Sonoran Desert. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: So, for a plant like this, to have some arms, at least 250 to 300 years have passed for them to have their arms. So a lot of these saguaros that we see here are easily three, 400 years old, so they're ancient saguaros.

BASCOMB: Some of these cactuses may have been here when the Spaniards were establishing settlements. But Sergio says the native people of the area, the Tohono O’odham, have always had a close cultural connection with the saguaro.

AVILA: The new year, or the year for the Tohono O’odham starts on July 1st, and that is connected to when the fruit of the saguaro drops from the plant and around when the rainy season starts.

BASCOMB: And he tells me the fruits of the saguaro are an important food for everything from mice and skunks to foxes and coyotes. Their flowers provide pollen for a variety of bats and birds. The shallow roots are crucial for holding soil intact during the monsoon rains. And the body of the cactus itself provides housing for a number of residents.

AVILA: Saguaros are like apartment buildings with cavities, and so little owls, kestrels, woodpeckers, many other birds depend on saguaros to live inside of these cavities.

Sergio Avila is a wildlife biologist, as well as an outdoor activities coordinator with Sierra Club. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Unlike the Sahara, the monsoon rains pour on the desert here each summer, and scientists say that makes it this the wettest desert in the world. So even in the dry season, the Sonoran landscape is teeming with life. But as captivating as it is, there is so much more to see. So, Sergio and I pile into our car and head up the mountain.

[SFX CAR DOOR SLAMS, DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We drive around a bend in the road and suddenly the saguaro are gone. Within 1000 or so feet of elevation gain, it’s too cold for them.

[DRIVING SOUND 1-2 SECONDS]

We pass a scenic overlook, Tucson lies below us, and from here it’s clear to see why these are called sky islands.

AVILA: The sky islands, here in Arizona and New Mexico and the adjacent parts in Mexico, are mountain ranges surrounded by grassland sort of deserts that make them look like islands.

BASCOMB: Back 15 to 20 thousand years ago, the climate of the southwest was much cooler and wetter. With the end of the last ice age, temperatures rose and desert came to dominate the landscape. But at higher elevations, temperate plants and animals were able to survive. Today those remnant biomes are marooned as mountain islands, surrounded by the sea of the desert.

Mount Lemmon. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: In this region of the sky islands, is the only place, or is the place where jaguars and black bears meet. It’s the place where you have northern birds like sandhill cranes, and birds from the tropics, like military macaws.

BASCOMB: The Sky Islands sit at the confluence of 4 different ecosystems, the Rocky Mountains to the North, the Sierra Madre in the South, and Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts. With so much diversity in one area, Sergio says, the sky islands are a biodiversity hotspot.

AVILA: So this biological region brings together a species from the north and the south that they don't meet in anywhere else.

[SFX CAR DOOR SHUTS]

BASCOMB: We get out of the car and walk along a small trail. The path we are on is actually part of the Arizona trail that goes from Mexico to Utah. We are driving up Mount Lemmon today but you can also hike the mountain in about 5 hours.

AVILA: I think right here we're at about 4500 feet of elevation. We've been going up on the mountain, and you can see a little bit of the change. Now we start seeing some oak trees. And I have to say, I'm pretty cold.

BASCOMB: I'm chilly.

AVILA: Yeah, yeah, let's go see what we see over here in the trees.

BASCOMB: We’re walking in an oak woodland, but dotted in the understory of a forest you might see in Pennsylvania are huge cactuses, waist high covered in orange and yellow flowers.

AVILA: This is a prickly pear. Eventually those flowers will turn into prickly pear fruit, which is a super juicy fruit that is a tremendous food source and water source for a lot of animals.

BASCOMB: It makes a good cocktail too.

AVILA: Oh, well I'm glad you mentioned that because part of the trip includes prickly pear fruit margaritas and that is a sky island staple. (laughs)

The Sky Islands are in the midst of four different ecosystems – the Rocky Mountains in the North, the Sierra Madre in the South, the Sonoran Desert to the West, and the Chihuahuan Desert to the East. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Oh perfect.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

AVILA: One thing I wanted to share, for example, this region has four different species of skunks.

BASCOMB: Really?

AVILA: Yeah, so it’s not, you know, just skunks, but we have striped skunks. We have spotted skunks, we have hog nose skunks, and hooded skunks.

BASCOMB: And are they all just as stinky?

AVILA: No! Those who are specialists in skunks actually say that different skunks smell different. Those who have experience with skunks can even tell one skunk species from the other from their smell. Which, you know, I think it's a level of skill that I don't know if I'm ever going to get to but…

BASCOMB: Do you really want to practice? [LAUGHS]

AVILA: Ah, exactly right. Like, what does what does it take to learn that? But it also speaks about … skunks, eat insects, skunks dig around for rodents, skunks might eat some reptiles. So the fact that we have four different species of skunks, in my mind says that we have a tremendous diversity of insects and rodents, and everything that is food for skunks, you know what I mean? We also have two different species of deer, white tail and mule deer, or black-tailed deer, that are adapted to a different elevation. We have four different species of cats in this region. The better-known bobcat, which is the short one with a short tail, and the mountain lion, or the cougar. And then the tree tropical ones, which are the ocelot, and the jaguar, the two spotted cats that come from the tropics. Having four species of cats, it's also an indication that we have a lot of different animals that can be food. And so the sky island region is a really good example of a whole ecosystem working together.

BASCOMB: So, these sky islands are a chain of mountains that start near San Javier, Mexico, 300 miles south of the border, and run into Aravaipa, Arizona, some 200 miles north of the international boundary. These mountains are a crucial corridor for migrating animals, like jaguar, that can migrate several hundred miles in search of territory and a mate. So, I ask Sergio how a high-security border wall could affect migrating wildlife.

Sky islands are mountains whose ecosystems are drastically different compared to their surrounding lowland environment. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: You might be separating populations of carnivores, you might be separating populations of herbivores that are making use of some areas. And so this rich diversity in our region is very important. And it's one of the things that is under threat, short term by the border wall and other infrastructure there, and long term by climate change.

[CAR SOUNDS, DRIVING]

BASCOMB: Back in the car, we head up the mountain again. At about 7,000 feet of elevation, the oaks and cactus give way to pine trees. It looks exactly like a typical forest in New England. Around the corner we need to stop the car.

SERGIO: So we're looking at two white-tailed deer on the side of the road. They look like really young fawns. I would say these are young, from this last summer. I wonder where mom is.

BASCOMB: We peer into the thick vegetation, but don’t see mom, so once the deer are safely across we continue on to the top of the mountain to the Mount Lemmon Ski Valley. That’s right, alpine skiing in Arizona.

SERGIO: We are at 9000 feet of elevation in the ski area, the top of Mount Lemmon. We are surrounded by a meadow of aspen. If you've ever been in Colorado, you will recognize these trees very quickly. And we are in front of this ski lift and it is snowing. And here we are prepared for a field trip in the summer in Arizona and we are super cold.

Mount Lemmon reaches heights of over 9,000 feet and its summit area receives around 200 inches of snow every year. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: I'm wearing shorts and a sweatshirt and I'm uncomfortable. The thermometer in the car says it's 35 degrees up here. There’s snow sticking in your hair.

AVILA: Yeah. I also wanted to say we are seeing different birds, we saw a robin. Seeing different colored birds, but it is very gray and clouds are very dense. And so even the sound is kind of like hard… It’s not very noisy right here and so we only hear the wind blowing in the aspen trees. It is pretty, but it is cold.

BASCOMB: When we were driving up here we saw signs that say snow plow ahead and beware of ice, and that sort of thing.

SERGIO: And we were laughing at those signs on the road. Yeah, what did we know?

BASCOMB: We're not laughing anymore!

SERGIO: We’re not laughing anymore, no!

The trail map for Coronado National Forest, outlining the Sky Island Scenic Byway. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: In terms of the climate and habitats, we’ve gone from Mexico to Canada in less than an hour. We warm up with some hot chocolate at the top of the mountain and then head back down the way we came. My ears pop with the sudden elevation change and I’m struck by the remarkable diversity one small mountain has to offer. And in the monsoon season, it’s different still, when a flush of life emerges to greet the rain and complete an entire life cycle in a matter of weeks. Far from the barren desert one might imagine, the Sky Islands of Arizona are full of surprises and well worth a visit nearly any time of year.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in the Sky Islands of Arizona.

Related links:

- Coronado National Forest

- Listen to Living on Earth’s most recent segment on the National Parks

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Ponderosa Pine Savanna

The Cassin’s Finch is right at home in a Ponderosa pine savanna. (Photo: © Tom Munson)

CURWOOD: Birders love the Sky Islands, where it’s one-stop shopping for both tropical and temperate birds, and BirdNote’s Mary McCann has more about the birds that call this landscape home, where fire can be a friend.

BirdNote®

Ponderosa Pine Savanna

[Western Meadowlark song]

We’re in a Ponderosa pine savanna.

A mountainside in Arizona’s Sky Islands shows a Ponderosa pine savanna, the result of a fire from several years prior. (Photo: Katja Schulz, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

[Western Meadowlark song]

Tall pines with bark the reddish-brown of terra cotta dot an open, grassy landscape flecked with blue and yellow wildflowers. The warm air is fragrant with the spicy scent of resin. Dry pine needles crunch beneath your feet.

[W. Bluebird calls]

A Western Bluebird flits from a gnarly branch, as a Cassin’s Finch belts out a rapid song.

[Cassin’s Finch song]

The trees here grow singly or in small stands, making it easy to walk through and admire this Western landscape. Upslope, the pines become denser, mixing with firs. Downhill, the trees give way to an open grassland, where a Western Meadowlark sings.

[Western Meadowlark song]

The Western Meadowlark favors the open grassland of a Ponderosa pine savanna. (Photo: © Gregg Thompson)

The open structure of this savanna, found on mountain slopes from the Rockies to the Cascades, results from recurring natural fires. Fast-moving blazes sweep through, burning the low vegetation but sparing the larger trees, which are protected by very thick bark.

After a fire, grass and wildflowers re-grow quickly, helping ensure that the meadowlark’s song will continue to ring across the hillside.

[Western Meadowlark song]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Sounds of the birds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Western Meadowlark: 23045 recorded by W.R. Fish; 106608 by R.S. Little and 137513 by G. Vyn; Western Bluebird 44896 by G.A. Keller; Cassin’s Finch 50197 and Pygmy Nuthatch 119403 by G.A.Keller.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2005-2017 Tune In to Nature.org May 2017/2019 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# savanna-01-2012-05-11 savanna-01

https://www.birdnote.org/show/ponderosa-pine-savanna

CURWOOD: For pictures, head on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related link:

Learn more on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Walking In Two Worlds” on Southwest, Cheshire Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – award-winning author Barry Lopez has a new book, Horizon. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Walking In Two Worlds” on Southwest, Cheshire Records]

Horizon by Barry Lopez

Horizon is a work more than 30 years in the making. (Image: courtesy of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Back in 1986, writer Barry Lopez won the National Book Award for his volume Arctic Dreams. He is a prolific nature and environmental writer, with critical acclaim for his other works including Of Wolves and Men. But, as time went on, he kept ruminating about a follow up to Arctic Dreams and now, after more than thirty years he’s published Horizon. It’s an expansive book full of reflections on his travels all over the world, with a focus on the current need for humanity to navigate through these treacherous times. Barry Lopez joins me from Seattle. Welcome to Living on Earth!

LOPEZ: Thanks, Steve, glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So this is a simple and yet huge question: why did you write this book, Horizon?

LOPEZ: I have made a life out of going away from my home. And sojourning in other places, Antarctica or Afghanistan, and on and on. And while I was doing that, and writing articles about those places, I was asking myself the question, why are you doing this? Are you just running away? Or have you actually accomplished something in all these years of travel? So I think that was the trigger for the book. What had I done as a writer? That incubated inside of me; when I signed the contract in 1989, everybody at Knopf basically gave me their blessing, and they said, "when you are ready, bring this book to us. Nobody's going to ask you about, 'what'd you do with that advance?'." [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

LOPEZ: So between signing the contract about 30 years ago, and writing the book, I wrote five or six other books and wrote a lot for magazines. But I had to get myself educated, I had to mature as a human being. And once I felt, roughly in my late 60s, that I could understand what the book was supposed to be about, then I started writing it. But it incubated, Steve, for a very long time.

CURWOOD: Of course, your book is an elegant song of praise to the interactions between people and place —

LOPEZ: Yes.

CURWOOD: — and you dwell on your own relationship with a recently clear-cut patch of forest in Cape Foulweather, Oregon –

LOPEZ: Right.

CURWOOD: So, so tell me why you started your practice of visiting this clearcut, and why it became meaningful to you.

Barry Lopez opens Horizon with a scene at Cape Foulweather, Oregon, where he muses on the legacy of Captain James Cook and another heroic, but unheard of, navigator named Ranald MacDonald. (Photo: Kirt Edblom, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

LOPEZ: I had for most of my adult life been intrigued with James Cook, and what he was up to, what he was about. And so I would read biographies and make notes and was going in no particular direction with that impulse. But I did know that, on his third voyage, he sighted North America and his landfall was at Cape Foulweather; they got there in a horrendous storm, and so he named the cape for the weather. And I thought, well I'll, I'll learn something, if I go over there and just sit quietly. So I went on these back roads, logging roads, and got some elevation, and camped in a clearcut where I could see, straight out in front of me, the Pacific. And I guess I went there 10 or 12 times and would camp there for a while. I didn't have an agenda. But I had tremendous curiosity about what this anonymous, and anomalous, place was. You know, I made a catalog of the plants and the birds, and was there in all kinds of weather. And to open the book, to open Horizon, I chose to go when a really big storm was moving in. I knew this storm was coming out of the Gulf of Alaska, and I thought, I'm going to go out to Cape Foulweather and, and weather the storm out there, just to get a little bit of a feeling of those few days when he was inside of Cape Foulweather. It was also a way for me to present a man named Ranald McDonald, who was born at the mouth of the Columbia River, he had a Chinook mother and a Scots father. And he didn't get the breaks in life that James Cook did, because he was mixed race. He was told in a very direct way that a person of mixed race like him had no business trying to approach or date a white woman. And he became the character for me that stood for modern times. We live in a mixed race culture, there's a mix of ideas, and the character of James Cook, although laudable, wasn't the full story. The world is full of characters like Ranald McDonald, who are heroic, but unheralded.

CURWOOD: You know, I view this part of your book as a fascinating take on, excuse the phrase, the 'great white hunter' phenomenon.

LOPEZ: Yes.

CURWOOD: And a commentary about, so who gets to make all these decisions about exploration? Who tells the story when you get there? And how do you, how do you get credit and support for doing something unusual like this, if, if, in fact, you are the guy that actually finds the game for the 'great white hunter'.

LOPEZ: I wanted, in this book, to set in motion the questions that you have just phrased. And throughout the book, I'm posing, I think, two questions that arise with Cook. And that is, all of us know hell is coming. You can call it global climate change, you can call it the disintegration of democratic forms of government, you can go anywhere and say, "this doesn't look good, this looks really bad". So the need to attack this issue, to me, is like one of the great voyages that we now have to choose to make: move into unknown territory, uncharted lands. So our model for that is this fellow Cook, and his ship. And my hope in the book is that people will say, we're in trouble. What is going to be the vessel on which we sail? And, maybe more importantly, who is going to be the navigator? Are the qualifications for a navigator today different than they were in the late 18th century? Oh my, yes. We have atomic weaponry, we have constant warfare, we have failing supplies of fresh water. We need a navigator the like of which we've never seen. So I think if you are doing your job as a writer, first of all has nothing to do with you; as the writer, you're the conduit, through which is coming something that maybe the writer doesn't understand. But it's an effort to put in front of people a vision of the world that allows them who have different expertises to say, "here's what we should do. This is how we take care of ourselves."

CURWOOD: You know, that book title, simply Horizon, there's no subtitle. 30 years ago, you picked it when you signed the contract.

The Captain James Cook statue in Christchurch, New Zealand. (Photo: Roger Wong, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

LOPEZ: Right, I did.

CURWOOD: Why? Why did you choose that title?

LOPEZ: The question that you've asked is one I ask myself, why did I choose that word for the title of the book? I had to write the book before I understood why the book is called Horizon. The book early on also had a subtitle, which I decided to get rid of because it was pretentious, and was not earning its place on the cover. I think especially with a big book like this, the process of editing is, in large part, is getting rid of the scaffolding. You set up the scaffolding to create the edifice, and if you want it to be seen in a clean way, you've got to get rid of all of that scaffolding. So the subtitle was a bit of scaffolding. And I looked at it one day and thought, "oh, give me a break."

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

LOPEZ: So the, the title and the subtitle were once Horizon: The Autobiography of a Journey. And it is an autobiographical book, and it is about the narrator's trying to grow up, trying to be a real person. And early on in the book, you know, I did something that was completely foolish and humiliating for me to discover in myself, which is a failure to understand that the other people are different from you, and you don't know; they do. And when I did that, I felt, I have to write about this, and I have to expose my vulnerability. And I have to make common cause with every reader who, all of us have done things we regret doing. And then, then you grow up. And so the whole book is about arriving at a position of impassioned embrace of all human beings. People often say to me, "well, you go to these exotic places, what's the key?" As though there was, you know. But the answer to that is, when you are in a place that is not your own, among people who are not like you, the first impulse always has to be respect. Even if you don't understand, you have to show respect for what is technically called another epistemology, another way of knowing the world.

CURWOOD: So to what extent would you say that Horizon tells the story of you discovering the Other?

LOPEZ: You're so good at this, Steve; it is that, I hadn't thought of that. But if you'd let me what I would say – yes, it is a story of the discovery of the Other. But I think it's a plea as well, to everyone to take the same journey, to realize the stakes are so high now that you must make common cause with all people. You could say, we need to rid ourselves of racism, and ethnic warfare, etc, etc. We aren't doing that, we're still living with that horror. But we have to discover a politics, for example, that takes place as though all those things have been accomplished. So you're saying to yourself all the time, "what would it be like, if we didn't have this racist horror drifting through American culture?" And then you have to make a politics that's founded on the fact that we were able to do that. Time is so short; you can sit down with people who make the models for global climate change, and what they all agree on since they started in the late 70s, is, we got some things right. Each time we do this, we get many things right. But the one thing we get wrong consistently, is how fast this is happening. So we have not too much time, and we need calm voices, common cause, compassion, empathy for all people who are in bad straits. And when we fall down, somebody helps us up, we have to be there when somebody else falls, and you help them up. If we can't make that giant leap, everything we pray for in our lives, in our different religions, is going to come to nothing.

CURWOOD: Your book is both searing in its indictment of the way we're conducting things, and our plight, and hopeful, so hopeful –

LOPEZ: Yes.

CURWOOD: — that somehow we are going to deal with these huge challenges that humanity is facing. Why?

Barry Lopez is the author of Horizon and sixteen other books. (Photo: John Clark)

LOPEZ: Whenever people say something nice about my work, or, or what I've done, I always point out that I had really good teachers. And I mean, I had great teachers in university, and then I went into cultural worlds different from my own, and there too, I had great teachers. They were not of my race, they were not of my religion. They weren't, they didn't speak my language. But these men and women helped me to understand what it means to be a grownup. And, you know, a grownup is somebody who no longer needs to be supervised, they can be left alone, to act on behalf of their people, without the fear that they're going to favor one group, or one age, or one gender over another. One of those people said to me one time, when I expressed doubt about myself and about the direction of the book, he said, "the only thing you can do wrong, is to destroy someone's sense of hope. For you, the sense of hope that they are carrying might be poorly thought out or untenable. But you cannot say that to somebody, you have to support them on their journey to arrive at a hopeful end." So I knew that I had to state in the book some of the terrible episodes that we all have experience with, or at least know about, like the slave trade. And we have to reckon with that. But I knew the book had to end with an elevation of the reader's spirit that was believable. Many of us have become cynical, because of the atmosphere around, if you will, the current occupant of the White House, we've become very cynical about what can be done. And we can't go into that place, we have to maintain a vision that, you know, is on the horizon, of a different way of doing things that is less harmful, less cruel. It's a request, I suppose, for a larger view of things than the horrible moment of the present. And I count on readers to come alive with this book and say, I now understand better what it is I really want for myself or my family or my children.

CURWOOD: And you're an optimist about that.

LOPEZ: There's no good thing that can be said about despair and pessimism. The whole thing is on the line right now, the entire meaning of the evolution of Homo sapiens. We either show that our power of invention is tremendous, or we show that the development of imagination in the hominin line was maladaptive.

CURWOOD: Barry Lopez is the author of the National Book Award-winning Arctic Dreams and his 2019 book is called Horizon. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

LOPEZ: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Horizon by Barry Lopez

- Barry Lopez’s website

[MUSIC: Time For Three (Featuring Jake Shimabukuro), “Happy Day” on Time For Three, by N. Kendall/arr. Rob Moose, Universal Music Classics (a division of UMG Recordings, Inc.)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joseph Winters, and Jolanda Omari. And we welcome Diego Arenas this week. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth