September 6, 2019

Air Date: September 6, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Amazon Tipping Point

View the page for this story

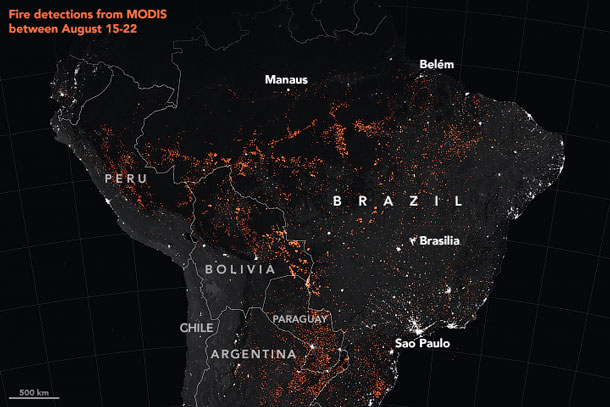

The fires in the Amazon rainforest are illuminating the alarming speed of deforestation in one of the most biodiverse places on Earth. Deforestation in the Brazilian part of the Amazon is on the rise again as Brazil’s President, Jair Bolsonaro, allows farmers and corporations bent on turning old growth forest into soy fields and cattle ranches. Now a “tipping point” could be near, putting the rainforest at risk of gradually turning into dry savannah. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb spoke with Carlos Nobre, senior researcher at the University of Sao Paulo, about what the continued loss of the Amazon rainforest could mean for nature and the global climate. (11:44)

Democratic Candidates Talk Solutions at Climate Town Hall

View the page for this story

On the evening of September 4th, CNN hosted a town hall event with seven hours of discussion surrounding the climate crisis. In back-to-back sessions, ten Democratic presidential hopefuls fielded questions from moderators and audience members alike on how they plan to address rising seas, environmental racism, and the fast-approaching deadline to curb global carbon emissions. We recount highlights from five of these ten candidates in the first part of our recap of the town hall. (06:23)

Reviewing the Climate Crisis Town Hall

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood sits down with Joe Aldy, economist and Professor of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, to take a look at carbon pricing, a just transition for fossil fuel workers, and other key topics from the climate crisis town hall. (09:34)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to take a look at the declining health of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Then, the two discuss how the United States became the world’s number one oil producer over the past year. Finally, with a look back into the history vaults, Peter tells the story of a bull shark found hundreds of miles from the ocean in the Mississippi River back in 1937. (03:38)

Underland: A Deep Time Journey

View the page for this story

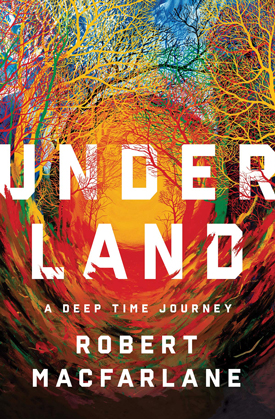

Many nature writers turn our eyes skyward, towards majestic mountains, open valleys, and wild rivers. But there’s a whole other world beneath our feet, in the dark and hidden places below the Earth’s surface—a place that the British author Robert Macfarlane calls the "Underland.” For nearly a decade, Macfarlane has been venturing into ice caves, exploring underwater rivers, and crawling through catacombs to discover this underworld, and he captures these travels in his latest book, Underland: A Deep Time Journey. Robert Macfarlane tells Living on Earth's Jenni Doering what drives him to explore the “deep time” that runs down below. (14:22)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Carlos Nobre, Joe Aldy, Robert Macfarlane

REPORTERS: Jenni Doering, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. The forest fires that continue to ravage the Amazon may push the largest rainforest in the world past a tipping point.

NOBRE: We might not have a lot of time, perhaps no more than 20 to 30 years to not only reduce deforestation to zero but also start restoring large portions of the Amazon forest.

CURWOOD: Also, ten Democratic presidential hopefuls take to the town hall stage of CNN to talk about the climate crisis.

SANDERS: People say, "Well, Bernie, you know you're spending a lot of money. Is it realistic?" And my response is, is it realistic to create a situation where the planet that our children and grandchildren will be living in will be increasingly uninhabitable and unhealthy? Is that realistic?

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Amazon Tipping Point

NASA’S Terra and Aqua satellite image shows areas of fire in orange, cities in white, and forested areas in black. (Photo:NASA, Earth Observatory, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

As the Earth continues to warm, there are more and more signs of how our climate is becoming unbalanced. More deadly and erratic hurricanes are one sign, crushing heatwaves another and wildfires are incinerating nature and communities around the world, from Alaska to Central Africa, South East Asia and especially this year, the Amazon.

Tropical zone farmers around the world often burn parts of the rainforest to clear the land and boost soil fertility. But it’s a temporary fix, as the soil is quickly exhausted, so to keep farming they have to keep burning deeper and deeper into the forest. Often called the lungs of the earth, what happens in the Amazon does not stay in the Amazon and Brazil had reduced deforestation rates over the last decade. But the new national government relaxed enforcement of conservation laws and there were three times as many wildfires this July as compared to the same time last year.

Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb spoke with Carlos Nobre, senior researcher at the University of Sao Paulo.

NOBRE: It's very rare natural fires in the Amazon. So we know when there are fires. It's mostly for expanding their agricultural frontier into the forest.

BASCOMB: And the new president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, has been nicknamed Captain Chainsaw for his attitude towards the Amazon. Can you tell me please more about his policies and rhetoric and how that's contributing in your opinion to this surge and fires there?

NOBRE: He called himself Captain Chainsaw. Just to illustrate his views on the way we should proceed with development in the Amazon. He does not believe the indigenous territory should be kept the way they are the he believes they should be transformed into big cattle ranches as well or open them up to mining. His views represent just a minority of people, which really do not have much power, except they are very close allied with the conservative agribusiness the conservative agribusiness sector wants perpetually expands the land for cattle ranches for agricultural. However, this is not necessary. And the Amazon and other parts of Brazil can produce a lot of food without further deforestation. It's simply a matter of increasing efficiency in Brazilian agriculture. And recent polls show that 90% of Brazilians are against Amazon deforestation, his views are the views of a very few people. And they are not really the views of Brazilians and Brazilians really care about the Amazon, not today but forever.

The Amazon is the world’s largest rainforest and acts as a major carbon sink. Its destruction could prevent meeting the Paris Climate Agreement goals of limiting global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius. (Photo: Matt Zimmerman, Flickr, CC By 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, let's talk a bit about why the Amazon is so very important even outside of Brazil, starting with its role as a carbon sink. What role does the Amazon play in the world carbon budget and how has that changed as a result of these fires.

NOBRE: So the Amazon as a natural sink, the forest removes something up to 2 billion tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere every year. This is about 5% of total emissions by human activity 70% combustion of fossil fuels and 24% deforestation and agriculture. So the Amazon alone removes 5% of that 40 billion tons. This is crucially important because otherwise, the planet would be warming up much, much faster than we are observing. If we lose most of this carbon stored in the vegetation, we are not going to meet the targets of the Paris accord of two degrees Celsius maximum warming or preferably 1.5 degrees Celsius.

BASCOMB: Well, let's talk a bit about water. The billions of trees in the Amazon produce an awful lot of water in the course of their lives. Can you tell me a bit about the role of the forest and the hydrology of the region and, and worldwide?

NOBRE: Tropical forests they have this very special characteristics, which is they produce photosynthesis all year round, because all this rain goes deep into the soil, they have very deep roots 10 meters up to 12 meters. So you don't see any seasonal variability photosynthesis in the production of organic material. And of course, the temperatures are very adequate for almost maximum optimal level of photosynthesis. Therefore, they keep transpiring water evaporating and transpiring we call evapotranspiration. And so that water is very important to induce the formation of clouds, clouds, droplets and rain. So tropical forests are the most efficient biome to recycle water. Many studies indicate that the without the forest, the overall rainfall in the Amazon would be something like 25% less. And if the rainfall is less, most of the forest, we will become a dry Savannah.

BASCOMB: And of course, the irony here is that this forest is being cut down for agriculture and the very crops and cows that require water will be harder to grow in the long term as rain fall pattern shift and the forest is degraded even further.

NOBRE: Absolutely, this is very true. You know, without the Amazon, we have many impacts on the possibility of agricultural one is yes, reduction of rainfall in distant remote areas. But also there is a direct effect of temperature, a tropical forest cools the atmosphere, because most of the solar energy reaching the forest is used to evaporate transpire water. And if you reduce the forest, more of the solar energy is used to heat up the air. So the air is warmer by two to three degrees centigrade. So the air is not only hotter over the forest, or what used to be a forest, but also when they travel southward, and they reach central Brazil, an area of agriculture, they will also reach that area to two degrees 1.5, 2 degrees warmer. And that's very damaging to agriculture. Because remember, this is tropics, this is already very, very hot places. Agriculture is, let's say almost at the limit in these areas in terms of temperature, so that will reduce productivity of agricultural and also cattle in in central Brazil.

BASCOMB: Now we hear a lot about the notion of the Amazon reaching a tipping point. That is where the whole system turns from rain forest to Savannah, how would that happen? And how far are we from such a tipping point?

Carlos Nobre studies the biosphere-atmosphere interactions and climate impacts leading to Amazon deforestation. He is the former Director of CEMADEN, Brazil’s national natural disaster monitoring and alert agency and is currently a Senior Researcher at the University of Sao Paulo. (Photo: Courtesy of Carlos Nobre)

NOBRE: This is one area that I've been working with colleagues and my PhD students for many, many decades. And recently we look at all human drivers deforestation, climate change due to global warming, and also vulnerability of forest to increased number of forest fires, we put all those three drivers together. And then we concluded that because all these three drivers are acting upon the forest simultaneously today we should not exceed the forest figure 20 25% of the forest. If we exceeded this range 60% of the forest will slowly over three to five decades turn into dry savannas. This is the tipping point. And we are currently something like 15 17% deforestation the whole basin. So we are not that far under the current rates of deforestation. This is something between 20 and 30 years into the future, very, very close to the present.

BASCOMB: If we do reach that tipping point, and the Amazon turns to Savannah, what does that mean for the world? What does that mean for you know, our own survival hydrology, the carbon budget, and so many other things that we maybe can't even anticipate?

NOBRE: Well, first, we have to be very concerned with the survival of 10s of thousands of species endemic to the Amazon, which will go extinct. So loss of biodiversity will be very significant by the Amazon forest is the most species diverse place on Earth, then probably we are going to lose over the course of a few decades, perhaps three decades, a very large amount of carbon, the dry savannahs store much, much less carbon maximum third, as much carbon as a tropical forest. So all that carbon ends up in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide making the possibility of reaching the Paris accord targets for 1.5 or two degrees, much harder, much, much harder. In fact, almost it makes impossible to reach it 1.5 target. So and also, of course, it changes the climate in the whole basin less rain, much hotter. And also, it will interfere remotely in, in climate in rainfall in many distant areas, perhaps even Southwest us but certainly Eastern South America.

BASCOMB: Well, this is all very depressing. What can a listener do somebody that's listening to us talking right now and feeling rather helpless about it? What can we do?

NOBRE: Well, we have really to to force the sector sectors exploring economics in the Amazon. So, it's very possible to have production of many, many products in the Amazon with zero deforestation policy. So, this is a possibility within our hands. But responsible consumption is a key element. And of course, when you go when you step higher, and you think about, let's say investment funds. Investment funds they own partly this big sigh companies meet companies, if these investment funds really have a policy of zero deforestation, their portfolios that would rapidly rapidly drive deforestation to nearly zero. I think, you know, consumers, they have the solution in their hands, it's more effective coming from that front, rather than, let's say, expecting the producers, agribusiness to be responsible or go along those lines on their own, they have to be forced to do it by the market. And also, we are going through a process in Brazil and many Amazonian countries that one should be careful expecting governments to take all these actions, they are probably not going to take those actions on the short run.

BASCOMB: Carlos Nobre is a senior researcher at the University of South Paulo. Carlos, thank you so much for taking this time with me.

NOBRE: Thank you very much for the opportunity.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “The Amazon is Burning”

- National Geographic | “What the Amazon Fires Mean for Wild Animals”

- The Chicago Tribune | “Is the Amazon Really ‘The Lungs’ of Planet Earth? No, It’s More Like Our Sink”

[MUSIC: Airto Moreira, “Hala, Tumba and Timbal” on Life After That, Narada World]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Ten of the Democratic presidential hopefuls participate in town hall forums to say how they will address climate change. That’s just ahead hear on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at SailorsfortheSea.org.

[MUSIC: Izzi Rozen, “Softly As In a Morning Sunrise” on Homeland Blues, by Oscar Hammerstein, Brownstone Recordings]

Democratic Candidates Talk Solutions at Climate Town Hall

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders called for about $1 trillion a year to be spent by the US government for the next 15 years on battling the climate crisis. (Photo: CNN)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

On September 4th, CNN hosted ten of the highest polling Democratic candidates for president in back-to-back town halls about the climate crisis. The historic, nearly seven hours of discussion gave candidates a chance to lay out in some detail their plans for curbing greenhouse gas emissions, and helping communities adapt to unavoidable impacts. No candidate doubted the urgency of the climate crisis, and many noted the United Nations says we have just 11 years left to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half to keep global average temperatures from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The questions were how and for how much. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders called for $16 trillion to be spent over the next 15 years, roughly a trillion dollars a year, or 5 percent of GDP.

SANDERS: People say, "Well, Bernie, you know you're spending a lot of money. Is it realistic?" And my response to them is, is it realistic to not listen to the scientists, and to create a situation where the planet that our children and grandchildren and future generations will be living in will be increasingly uninhabitable and unhealthy? Is that realistic? So, I think we have a moral responsibility to act, and act boldly. And to do that, yes, it’s going to be expensive.

CURWOOD: CNN moderator Anderson Cooper asked Senator Sanders how he could accomplish his goals of Medicare for All, tuition-free college, and his climate plan all at the same time.

SANDERS: Well, I have the radical idea that a sane Congress can walk and chew bubble gum at the same time. [LAUGHTER] And you know, Anderson, there are so many crises that are out there today. It is not prioritizing this over that. It is finally having a government which represents working families and the middle class, rather than wealthy campaign contributors. [APPLAUSE] And when you do that… [CHEERS] and when you do that, then things fall in place.

CURWOOD: Questions from CNN journalists and members of the audience put candidates on the record on a range of topics from fracking, to carbon pricing, to nuclear energy.

Senator Sanders called nuclear power too expensive and problematic with waste. Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren said she’d start to phase it out. But entrepreneur Andrew Yang pointed to the promise of safer thorium-fueled reactors, and New Jersey Senator Cory Booker said nuclear must be part of the transition to a carbon-free economy.

Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) says the US needs to be at zero carbon electricity by 2030, and points to nuclear energy as a crucial part of that plan. (Photo: CNN)

BOOKER: My plan says that we need to be at zero carbon electricity by 2030. That’s 10 years from the time that I will win the Presidency of the United States of America. [LAUGHTER] And right now, nuclear is more than 50% of our non-carbon-causing energy. So, people who think that we can get there without nuclear being part of the blend, just aren’t looking at the facts.

CURWOOD: All the Democrats on stage pledged to bring back environmental protections that President Trump has gutted. Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar.

KLOBUCHAR: Right now, we have a leader that doesn't even think at all in the long term. And there is an old Ojibwe saying that is important to me -- we have a lot of tribes in our state -- and it says “great leaders should make decisions not for this generation but for seven generations from now.” [APPLAUSE] We have, we-- we have a president that can't make decisions seven minutes from now, OK?

Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar at CNN’s climate crisis town hall. (Photo: CNN)

CURWOOD: Former Vice President Joe Biden lamented the vacuum left by President Trump’s decision to pull the U.S. out of the Paris climate agreement.

BIDEN: The deal is now, what's happened is that, as we have pulled out, there is no leadership. There is no leadership. I know almost every one of these world leaders. If I were -- if I had been president today, I would have at the G7 made sure this became the topic. There would be no empty chair. I would be pulling the G7 together. I would be down with the president of Brazil saying, “enough is enough. This is what we're going to do, and this is what's going to happen if you don't do it.” This is -- to bring the world together.

CURWOOD: Mr. Biden was asked about how realistic he thinks the Green New Deal is.

BIDEN: I think the Green New Deal deserves an enormous amount of credit for bringing this to a head in a way that it hasn't been before. It hasn't been. But it doesn't have a lot of specifics about exactly what we'll do with regard to greenhouse gases. And it doesn't have specifics of what programs are you going to initiate to be able to deal with taking -- getting a net zero emission. What programs are you going to move on? What are the things we should be doing? Where should the focus be?

Former Vice President Joe Biden called for the United States to return to its position as a leader in the global battle against the climate emergency. (Photo: CNN)

CURWOOD: Several of the candidates stressed the importance of structural changes, such as getting corporate money out of politics and putting a price on carbon, rather than individual actions.

CNN moderator Chris Cuomo asked Senator Warren about President Trump’s decision to roll back rules calling for energy-saving lightbulbs.

CUOMO: Do you think that the government should be in the business of telling you what kind of lightbulb you can have?

WARREN: Oh, come on, give me a break. [AUDIENCE LAUGHTER] You know...

CUOMO: Is that a yes?

WARREN: No. Here's the -- look, there are a lot of ways that we try to change our energy consumption, and our pollution, and God bless all of those ways. Some of it is with lightbulbs, some of it is on straws, some of it, dang, is on cheeseburgers, right? There are a lot of different pieces to this. And I get that people are trying to find the part that they can work on and what can they do. And I'm in favor of that. And I'm going to help and I'm going to support. -- But understand, this is exactly what the fossil fuel industry hopes we're all talking about. [APPLAUSE] That's what they want us to talk about.

Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) spoke at length about environmental justice and the fossil fuel industry. (Photo: CNN)

CURWOOD: And like some of the others present, Senator Warren spoke at length about the importance of environmental justice.

WARREN: So, I see it this way. Part one is that everything we spend on climate has to be about reducing our carbon footprint. It has to be about justice, as well, though, for people who have been displaced, for workers who have been displaced, for people in communities of color. It's about trying to help those who've been injured from all that's happened.

Related link:

CNN | “CNN’S Climate Crisis Town Hall”

Reviewing the Climate Crisis Town Hall

September 4th was the first the top ten Democratic candidates for President in 2020 had ever gathered to talk about climate in a lengthy national broadcast. (Photo: CNN)

CURWOOD: We’ll have more about the US presidential candidates in next week’s program. Joining us now is economist Joe Aldy, he’s a public policy professor at Harvard University’s Kennedy School. Welcome back to the show, Joe.

ALDY: Thank you, Steve. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: So, you were in President Obama's White House. So, among all these candidates, do you have a dog in this fight?

ALDY: I look forward to a democratic president making some real progress on climate change. So, I don't have a dog in the fight. I'm not working with a campaign. But I'm thrilled to see a lot of the policy ideas they're bringing forward.

CURWOOD: So, this is the first time that a major news network has gathered 10 top Democratic presidential hopefuls on a stage to have them talk about climate change at length. Why do you think it took so long for us to get here?

ALDY: Well, it's fascinating, you can go back and look at, say, the 2012, or the 2016 presidential debates and climate change is barely mentioned at all. And I think it's really impressive to see the change in where we are in terms of the public debate about this issue. I think a lot of credit can be given to the students out there, who have really started to bring energy from a new voice to the debate. And I think that has helped really drive both the candidates to be much more ambitious. And for the media to start to really pay attention to the climate change issue.

CURWOOD: I saw the students asking tougher questions, than many of my journalistic colleagues would have asked given the opportunity,

ALDY: I was impressed at how well the students did, and I thought a few of the anchors maybe should go back to school.

CURWOOD: Now, carbon pricing figured fairly heavily in this series of town halls, whether it's cap and trade or a carbon tax, break those concepts down for us briefly.

ALDY: Regardless of whether it's a carbon tax, or cap and trade, the general intent is to put a price on the pollution that comes from burning fossil fuels, that then makes it that much more expensive to burn coal or burn gasoline or to use natural gas. That creates the incentive, then to one become more efficient in how we use energy, it also creates a much stronger incentive then to invest in solar energy and wind power. And so, the idea here is to say, we don't necessarily know in government the best most cost effective way to reduce emissions. But if we put a price on the pollution, we’re going to create incentives for companies and for families, to find the lowest cost way of reducing their emissions. Now, the difference between a tax and cap and trade, though is that a tax is explicitly setting the price, cap and trade sets an aggregate quantity and emissions goal, and then gives firms the right to emit that they can buy and sell with each other.

Presidential candidates had to navigate criticisms of the fossil fuel industry while ensuring a just transition for the industry’s workers. (Photo: Lindsey G., Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, if cap and trade and carbon taxes both reduce carbon, which one is the better approach?

ALDY: Which one's the better approach? The one that can get signed into law? There's two key characteristics that will impact the effects of those policies on the typical American one is going to be do we use these revenues to benefit them or not? The second thing is a question of, do you want to have certainty on the emissions outcome? In which case, you might like cap and trade? Or do you prefer certainty about the price and the cost of the policy, in which case you might like a carbon tax. But as someone who worked on cap and trade in a failed effort in 2009, and 2010, in government, there's also a part of me that's willing to try a carbon tax to see if there's a way you can navigate the politics to get it through Congress. At the end of the day, I think it's really important for us to price carbon as a key tool in any kind of climate change program. So, I think they're both a tremendous step forward from our existing authorities under current law.

CURWOOD: Now, there were several questions, Joe, that focused on what personal sacrifices the American public would have to make to deal with climate disruption, weather will be giving up cheeseburgers, incandescent light bulbs, others focused on the fossil fuel companies pointing the finger to them as the biggest contributors to this crisis and their role in disinformation, your take.

ALDY: I think that if we're talking about plastic straws, we're not focusing on what's really important here. We need to change the energy foundation of our economy. So virtually every activity a business undertakes a family undertakes in a given day, has some impact on the climate. That's why we need to have really strong ambitious climate change policy. There are big problems like this that we can't just solve on our own. Focusing on personal sacrifice, I think is missing the point that we need effective public policy to drive changes in behavior in the near term, and incentives for innovation in the long term.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think the talk about personal sacrifice is pushback from folks who don't want to see us move ahead on dealing with climate disruption?

ALDY: Well, wouldn't surprise me we've seen different ways of framing a problem to try to slow down progress. It's one of my colleagues refers to this as the solution aversion problem, some of the people who when you pull them publicly why they aren't sure about climate change, they may be denying climate change is not that they are really denying the science of climate change, they may be averse to the potential solutions, and they think there's potential solutions may be really uncomfortable for them, or really expensive for them. And so, that may be the reason why they don't necessarily support taking action on the issue.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the big worry that many have about changing our energy economy to deal with climate change. And that's, of course, jobs. And when you shut down coal mines, or you close down oil fields, and such people lose jobs, not just the people but the communities. So how did the folks on the town hall stage deal with the question of having what some would call a just transition.

Though Washington Governor Jay Inslee has left the Democratic primary race, his strong plans for battling the climate crisis left a clear impression on the candidates still in the running. (Photo: Governor Jay Inslee, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

ALDY: So, for some of these industries, they're already undergoing a transition. Coal is undergoing a transition; we have seen employment in the coal industry fall quite dramatically over the past decade. And while there are some who would blame environmental regulations for that, I think that's for the most part a testament to market forces. It's been the success of innovation in fracking that has driven down dramatically, the cost of producing natural gas that has helped natural gas dramatically increase its market share in the power sector and displace coal. So right now, we're just relying on the markets, which to be honest, markets don't care if a job is lost at a coal mine, because the job is created at an oil and gas field. Markets can be ruthlessly efficient in that way. And right now, without any policy framework, those cold communities in Appalachia are hurting without a policy response. We saw a number of the candidates describe how they could envision a way of providing resources to help in the short term, the potential for trying to provide training the potential to diversify those economies. I mean a coal miner who loses his or her job, it's not just that they want to have money to help support the family, they do. But there's also the self-esteem and the confidence of doing something productive with your day that comes with being employed.

And I'll be honest, dealing with this, when we think about the number of jobs as tech with coal is going to be easier than when we think about more broadly with fossil fuels. The employment in oil gas is dramatically higher, both directly for oil and gas drilling. And for those who service oil and gas operations. The question, of course, is do we find there to be opportunities in the production of turbines for wind farms, or solar panels or the next generation of energy efficient technologies, where we are creating good paying manufacturing jobs, that the next group of workers coming into the workforce instead of going into a fossil fuel industry job they're excited to go into a clean energy industry job. And I think that's, that's one of the key challenges that we have. You know, I think there's a lot from the plans that we heard in the town hall, where they can candidates are looking at that opportunity for creating jobs and a new growing industry that can help offset some of those losses in the others.

CURWOOD: Joe, we're just about out of time, but from your perspective, who helped themselves in this process, do you think?

Joe Aldy is an economist and professor of public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School. (Photo: Courtesy of Joe Aldy)

ALDY: My first answer will be Jay Inslee. Now, it's fascinating, he wasn't on stage speaking. But I think Governor Inslee brought a lot of ideas and enthusiasm about climate change. It didn't resonate enough for him to stay in the campaign. But having said that, you heard a number of the candidates talk about the very thoughtful plan that he has brought to the table, the fact that he organized campaign around climate change. It says to me, it says something that you can be a governor of a state and as a governor, you have to care about a lot of issues. But when he just said, I'm going to run for president, this is the number one issue. This is the fundamental issue facing America in the 21st century. So, I think the fact that he has these ideas, I think the term was using their sort of open source. I thought that was fantastic. And I think it reflects that among Democrats, this that issue that they take very seriously. You know, there are some who I thought did a great job. I thought Senator Warren did great. Senator Warren, I think is great when she is passionately talking about how public policy can better the lives of Americans. And I thought, you know, there was some we were frustrated. We didn't have a debate. I think it was good. We didn't have a debate. Climate change isn’t simple. And so, you know, my friends in communications say you got to figure out a better way to talk about climate change. But sometimes you need to talk about difficult, complicated issues in depth, and I thought the format in the town hall provided that opportunity.

CURWOOD: Joe Aldy is an economist who teaches at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. Joe, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

ALDY: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- The New York Times | “CNN Climate Town Hall: Here’s What You Need to Know”

- Joe Aldy’s biography

[MUSIC: Norah Jones, “Not Too Late” on Not Too Late, by N. Jones/L. Alexander, EMI/Blue Note Recordings]

Beyond The Headlines

The health conditions of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia have been recently declared “very poor”. (Photo: Flickr, Tchami CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's time now to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with environmental health news. That's EHN, Oregon daily climate.org. On the line now from Atlanta. Hi there, Peter, what's going on? What do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve, we're going to take a look at Australia and the Great Barrier Reef, that natural icon. It's also a hugely important economic factor for tourism and Australia. The Australian Government, already concerned about what they call the poor status of the Great Barrier Reef have downgraded it to very poor. There are pollution and other factors that are degrading this thousand-mile-long reef, but the main one is simply climate change.

CURWOOD: So, if it's been downgraded to very poor, what comes after that, because I mean, the oceans getting warmer.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, I don't know what comes after that is maybe the death of the reef, extinction of the reef. Around the world coral reefs have taken a nosedive just in the past few years. Coral bleaching pollution from settlement hits by ship traffic, even sunscreen, the chemicals and sunscreen have been found to be very harmful. But the main culprit is warmer water because reefs have a very limited range of temperatures in which they can thrive and survive.

The United States has been the number one in oil production worldwide since 2018. (Photo: Flickr, Rennett Stowe CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: I believe at one point, the Australian government wanted to cut a ship channel right through the Great Barrier Reef.

DYKSTRA: They did. And the irony for all that is that they wanted to make a shortcut through the reef in order to ship coal to places like India and China, thereby destroying a part of the reef even quicker in order to get coal out. That would help warm the oceans that would kill the reef potentially off forever.

CURWOOD: That's incredible, isn't it? Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hey, the USA is number one. In the past year, this country has taken the lead in oil production. The US is now the number one oil producer thanks mostly to fracking. And the US being number one changes two things. It changes probably not for the better how this country deals with foreign policy. And it also changes, of course, the climate,

CURWOOD: The Saudis are still pretty big producers, as is Russia. So, it seemed that those are competitors for the US. And yet, I suppose maybe they're also companeros that they would like to see the continued use of fossil fuels?

DYKSTRA: Competitors and business but companeros in delaying climate action. The Russians played a big role in, that the Saudis certainly have. And now with the current administration in Washington, the US is now the world's leader in climate denial.

CURWOOD: That's not such great news. Peter. Maybe you have some better news for us on the history vault.

DYKSTRA: Well, not good news or bad news, but certainly interesting news. September 6 1937, two fishermen in the Mississippi River of Alton, Illinois, that's just north of St. Louis. Catch a bull shark. It's okay to say bull shark on the radio.

Despite most sharks residing in saltwater, bull sharks can travel in brackish and even freshwater for limited amounts of time. (Photo: Flickr, Daniel Kwok CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: As long as it's that kind of bull, yeah.

DYKSTRA: Well, saltwater creatures, but they've also been known to show up far upstream and places like 2000 miles up the Amazon River even farther north in the Mississippi. They've been found off Davenport, Iowa. Bull sharks can live a long time and freshwater they've even shown up in the Potomac.

CURWOOD: That's near Washington, DC.I thought you weren't going to talk about that kind of bull.

DYKSTRA: Different kind of bull shark entirely.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Okay, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news and ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon!

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website loe dot org.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Australia Cuts Outlook for Great Barrier Reef to ‘Very Poor’ for First Time, Citing Climate Change”

- CNN | “America is now the world's largest oil producer”

- In Fisherman | “Sharks in Illinois”

[MUSIC: Mary Chapin Carpenter, “Holding Up the Sky” on The Age Of Miracles, Zoe Records]

Coming up – A deep dive into the world beneath our feet with the new book, Underland. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, “Michelle” on Flight of the]

Underland: A Deep Time Journey

“Darkness is an illumination down there, as well.” – Robert Macfarlane (Photo: Joshua Sortino on Unsplash)

Many nature writers look skyward, towards majestic mountains, open valleys, and wild rivers. But there’s a whole other world beneath our feet, in the dark and hidden places below the Earth’s surface. This is the place that the British author Robert Macfarlane calls the "Underland.” For nearly a decade, he has been venturing into ice caves, exploring underwater rivers, and crawling through catacombs to discover this hidden world that can be both beautiful and macabre.

His latest book, Underland: A Deep Time Journey, documents these travels and explores the human relationship with the "deep time" of down below. Living on Earth's Jenni Doering spoke with Robert Macfarlane.

DOERING: So, let's start off with a big question. What is the underland?

MACFARLANE: Yes, that is a very good question. And I guess there's a 500-page answer to that. But the short version of that would be all that, all that lies beneath us, and particularly, that which lies below the surface of the land. And it's a place that we have shunned and been frightened by, but also been drawn to for as long as we have been anatomically modern humans and indeed longer than that. So, I wrote a book about mountains a very long time ago, which tried to work out why people go high; this, this is an attempt to answer the question of why people go low, and what they find when they do.

DOERING: You say that we tend to shun the underland. Why is that?

MACFARLANE: It's dark, it's dirty, it's hard to get anywhere. It's associated with death, with mortality, with confinement, exploitative labor practices, incarceration. It has a pretty bad rap, but it is also teeming with wonder and secrets. And those are its two sides. Darkness is an illumination down there as well.

DOERING: It's amazing what's just underneath the surface.

Underland: A Deep Time Journey explores the little-known world beneath our feet. (Photo: courtesy of W. W. Norton)

MACFARLANE: Yeah, that's it. I, I say really early on in the book, look up and you can see literally trillions of miles on a clear night. You look down, and your sight stops at the ground. And yeah, and that's why we know so little, because we are so kind of optically charged in our knowledge.

DOERING: I mean, it seems to hold this incredible power for you as you’re journeying through, as you're going through the catacombs in France and this underground river running through Italy.

MACFARLANE: Yeah.

DOERING: I mean, reading your book, it almost felt like you were traveling to Hades and back.

MACFARLANE: [LAUGHS] Well, someone just introduced me to this great musical of yours, Hadestown, which just cleaned up at the Tonys. So, I have some of the songs from Hadestown going through my mind, but I think there is a great playlist to be made from the underworld songs, the jams going underground... Anyway, so it goes. But yeah, it's it's a zone of myth. Hades is one of those; classical myth is filled with what they call the katabasis, that journey down into the underworld often to retrieve something of value, a loved one; or to consult with somebody, the dead about the future. And I guess that that it did come to have that, that pull for me. But I was always guided, okay. The book is filled with these mycologists and glaciologists and all people who have intense relationships with what lies beneath imaginative, or, or otherwise. And they cast the light, they held the light for me.

DOERING: The subtitle of your book is " A Deep Time Journey". Can you explain what deep time means to you?

MACFARLANE: Yeah, deep time is, is a phrase actually, that John McPhee, that great nonfiction writer comes up with, New Yorker writer. But it's an old concept, as old as geology. But basically, it is Earth history in its full units of age and ancientness -- the epoch, the Eon, the era -- not the minute, the second, the week, the year. Deep time crushes our units to a wafer, really, to an irrelevance, it seems. But so deep time means Earth historical time. But I think what's striking to me about the Anthropocene, arguably, is that we have accelerated, we have shallowed, deep time; or we've scrambled deep time and suddenly all these things -- we burn Carboniferous-era fossil fuels to melt Pleistocene-era ice to determine Anthropocene future climates. And suddenly, deep time is no longer sequential and orderly, if it ever was, and it's, it's muddled. And that's an unsettlement for us.

Entrance to an underground river in Slovenia, part of the “starless river” system Macfarlane describes in his book. (Photo: Martijn Booister, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: How did you choose the places that you wanted to visit for this book?

MACFARLANE: They chose themselves. I -- this may be a post-op rationalization, but it did feel afterwards as though I was uncovering a kind of buried structure that already existed. I knew I wanted to write about deep time, I knew I couldn't only do that in my own body and my own voice, because I am a shallow time human being. [LAUGHS] And so there are parts of the book that are told, not by me, but just they move around within the deep time history of the underworld and around the geography of the globe, as well as in Gaza, or they're in the Cretaceous, or they're in America where nuclear waste storage facilities are being constructed in Yucca Mountain and so forth. But the main parts of the book occur in Britain, then in central and Eastern Europe, and then in the north, and the Arctic. And that that's just the way it fell out.

DOERING: There's a lot of nature in this book, of course, but there's also man-made structures, like I'm thinking of the catacombs under Paris, France. And so, you traveled down there. What was it like to be down there in the catacombs of Paris, France?

MACFARLANE: The first thing to say is I was down there for two and a half days, which is the longest I've ever gone -- which isn't very long, but is longer, I suspect than most people have gone without seeing the sky or the sun or the surface or anything. And I went down with an amazing person called Lina, who was generous and bold and brave and rather different underground than she was above ground. She was gentle in both places, but she was quite quiet above ground, but had to be quite decisive. And she had this amazing navigational ability down there. She really didn’t consult a map. She’s been down there lots and lots, and she could just map it in her brain. It was like she had GPS for the catacombs. [LAUGHS] So, we yeah, we spent time down there sleeping in the dark, and you do lose track of time. And you also realize you're in limestone, which is, which is a rock made of, of death, basically of accumulated bodies of marine microorganisms, and also filled with the dead of Paris.

Deep time: the Grand Canyon reveals rock layers laid down over hundreds of millions of years. (Photo: morais on Unsplash)

DOERING: The Underland seems like such a place that evokes extremes of emotion -- wonder, as well as fear. How did these emotions manifest for you, in your explorations of the Underland?

MACFARLANE: That's a great question. And I was a conduit in a way; I mean, we have mined from it meaning as well as resource. So, I'm just one of, you know, a billion billion meaning makers. But there was one point in Norway where I, I just wept. When I, when I got into this deep sea cave, where cave art had been made about two and a half thousand years previously by really marginal, what we would call Bronze Age, and together is Peri-Arctic, peripatetic people. And then they painted these figures, the red dancers, out of iron oxide on the cave wall, deep inside this Granite Mountain, in a brutally wild place. So, and when I finally got there, after a really hard winter journey on my own, I was overcome.

DOERING: You worked for nearly a decade on writing this book. How did your relationship with the underland evolve over time?

MACFARLANE: Well, yeah, you're right that the idea first came in about 2010. And that was the year of the Deepwater Horizon blow-out, of the Icelandic volcano eruption, of the Chilean miners trapped underground. It was a real underworld year. I really started working in 2012. I think I -- a couple of things. One is I began to understand deep time as running forwards as well as backwards. And the second was just the age of the time we have spent being drawn into darkness. I wrote this book about mountains and, and why we're drawn to mountain tops. But that is so young, that is just punk-ishly young, that cultural impulse [LAUGHS], not even 300 years old. But we have been going into the darkness as a species, leaving those prints on the cave wall, those handprints on the cave wall that we've all seen the images of, for tens and tens and tens of thousands of years. So, something is at work there. And that is inexhaustibly fascinating to me.

Neolithic burial mounds at Knowth, Ireland. In Underland Robert Macfarlane explores the ancient human practice of burying our dead. (Photo: 1sock, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: As you've alluded to, humans have used the underland for -- I guess, as long as we've been around, almost? What are the different ways that we've found it useful to us?

MACFARLANE: Well, I say early on, but it took me a long time to work this out, that I think I call the three great tasks of the Underland. And they are to shelter, to yield and to dispose. So, to shelter is -- you know, where we put the bodies of our loved ones in a way to keep them safe, so we can go back and meet them again. It's where the Germans are putting all of their state documents and microfiche, or at the Svalbard Seed Vault, we're putting all of the, as much of seed biodiversity as we can in storage. So, that's this sheltering. And then yield -- obviously, we're a mining species, we're a burrowing species, we've drilled 50 million kilometers of oil borehole alone. We've mined so much wealth out of the earth. So, we go, we go to take knowledge, we go to take matter. And then dispose is where we put the stuff we don't want. Our nuclear waste, our sewage. The Cloaca Maxima in Rome was the -- yeah, the great, basically the great sewer at the heart of Rome, that Rome would just chuck all its stuff into. So, the underworld is our sump, is our shelter and is a treasure chest.

DOERING: In your book, you're thinking about the past, you're also thinking about the future. And you asked this really interesting, unique question: are we being good ancestors? What do you think the answer is to that?

MACFARLANE: No, no, no, we're not. And I think we're being asked to think more and harder about ancestry now in but in the sense, not of backwards in time, but forwards in time. And for me, that is, that is the deep time of this book, is actually not just the stuff which falls away behind us for billions of years, but what we're leaving.

Robert Macfarlane and two companions spent days wandering the labyrinthine catacombs underneath Paris, France, where ossuaries such as this one hold the remains of more than six million people. (Photo: Dave Shea, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Do you think there's anything we can do to do a better job of leaving a good future for those who come after us?

MACFARLANE: Yeah, I do. There are countless things we can do. I mean, if we think just in terms of Anthropocene future fossils, like what, in a very literal way, what will be our future fossils? It doesn't look great. We're going to leave lots of sheep, cow and pig bones behind. We're going to leave an absence of surface soil; we're going to leave an absence of biodiversity. We're going to leave a massive spike of nitrogen. We're going to leave radionuclides from our testings, we're going to leave fly ash and lead. It's a pretty good ugly record, particularly those extinctions and the habitat loss; that might be our script. So, I would love us to exit the Anthropocene and turn up in a -cene called something like the symbioscene, or the mutualcene, or the sustainability-cene, but it's -- we've got to, we've got to actually, for so many reasons.

DOERING: Robert, is there a passage that you'd like to read for us from your book?

MACFARLANE: Well, thinking about what we've been talking about, about the Anthropocene about things surfacing about time running fast, as well as slow, I'll read you a bit about a section from an extraordinary event, a calving event at a glacier, way up the remote east coast of Greenland in 2016. And I mention the year because that was a year of intense melt. Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, was at 22 degrees C, which is not what Greenland's capital should be feeling in that the ice cap was melting, the glaciers were running and calving fast, and we saw this extraordinary event.

In forests such as Epping Forest outside London, trees are linked via roots and fungi in an intricate underground network known as the “wood wide web.” (Photo: M W Pinsent, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

"'There!' shouts Bill, but we're all already looking there, where the first block fell, for it seems that a white freight train is driving fast out of the calving face of the glacier, thundering laterally through space before toppling down towards the water. And then the white train is suddenly somehow pulling white wagons behind it from within the glacier, like an impossible magician's trick. And then the white wagons are followed by a cathedral, a blue cathedral of ice complete with towers, and buttresses all of them joined together into a single unnatural sideways collapsing edifice. And then a whole city of white and blue follows the cathedral. As we shout and step backwards in voluntarily at the force of the event, even though it's occurring a mile away from us. And we call out to each other in the silence before the roar reaches us, even though we are only a few yards from each other. And then all of the hundreds of thousands of tons of that ice city, collapse into the water off the fjord, creating an impact way 40 or 50 feet high.”

DOERING: And you go on to write about how you are filled with this sense of dread.

MACFARLANE: Yeah, it was a dreadful event. Something else happened later, which is that a huge calving event happened from underneath the water. So obviously glaciers have a mass below the waterline and what I was describing there was a huge calving event that was coming from the above water face, pulling and pulling this ice out of itself. But also, what was happening under the water is a massive calving was happening under the water. Because ice is more buoyant in water it comes up and up came this huge, dark blue black pyramid of ancient ice. And for me, this was something out of an early 20th century horror novella. But what it was, was time itself rising up out of sequence, and of course glaciers do this, this is what they do. They're rivers of ice. But, but we are accelerating them as we are accelerating time in all sorts of ways. And, and for me that emblematic moment was an Anthropocene moment.

CURWOOD: Underland author, Robert Macfarlane, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Towards the end of his Underland journey, Robert Macfarlane descended into a moulin, a chasm carved into glacial ice by meltwater. (Photo: Destination Arctic Circle, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Related links:

- Underland: A Deep Time Journey

- The Atlantic | “What Lies Beneath”

- About Robert Macfarlane

[MUSIC: Izzi Rozen, “Shir Hanoded” on Homeland Blues, traditional, arr. Izzi Rozen, Brownstone Recordings]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with sounds of the Earth…

[SOUNDS OF RUMBLES AND BURPS]

CURWOOD: These are Earth sounds as you’ve probably never heard them – sped up 10,000 times and transposed up about 13 octaves…

[MORE EARTH SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: The sounds come from seismic recording stations in North America and Central Asia –

[MORE EARTH SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: The frog-like burbs you can hear are earthquakes, large ones followed by the chirps of aftershocks.

[MORE EARTH SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: John Bullitt created this unusual soundscape of our solid, restless planet for the CD Earth Sound.

[MUSIC: Izzi Rozen, “Shir Hanoded” on Homeland Blues, traditional, arr. Izzi Rozen, Brownstone Recordings]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth