December 4, 2020

Air Date: December 4, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Pandemic And American Hunger

View the page for this story

The coronavirus pandemic has exposed the perilous economic state of many households in America, with one in four U.S. households experiencing food insecurity in 2020 despite an abundance of food overall. Frances Moore Lappé, the author of Diet for a Small Planet and founder of the Small Planet Institute joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about food insecurity in the U.S. and why combating it should be a priority for the incoming Biden-Harris administration. (13:05)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s Beyond the Headlines segment, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Jenni Doering talk about the naming of the first African American Cardinal in the U.S., a prelate who has become a climate champion within the Catholic Church. Next, they discuss Superfund sites in Georgia that are threatened by rising seas, intensified rain and other climate impacts, and in the history calendar, it’s 40 years since the Superfund program was signed into law. (04:10)

Ghanaian Climate Leader Wins Goldman Prize

View the page for this story

For Ghanaian environmental activist Chibeze Ezekiel, the climate and pollution risks of a proposed coal-fired power plant in a coastal fishing community of his country were too high. So he organized a grassroots youth campaign and convinced the government to drop coal and invest instead in renewable energy. He’s a recipient of the 2020 Goldman Environmental Prize and joins Host Jenni Doering to talk about the campaign and powering Ghana sustainably. (08:33)

Troubles For Science Research In The Pandemic

/ Jes BurnsView the page for this story

When the world started locking down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, scientific researchers were not exempt from having to adapt their jobs to social distancing and remote working. Jes Burns of Oregon Public Broadcasting brings us the story. (04:27)

The Road To Darwin

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth's Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender tells of his and his wife's encounter with a black panther while driving along Australia's Stuart Highway. (03:47)

Migrations: A Powerful Novel About A World Losing Life

View the page for this story

In the 2020 novel Migrations set in the future, polar bears are extinct. So are chimpanzees and wolves and big cats. For the novel’s protagonist, this mass extinction is personal. So, she does the first thing that comes to mind: she makes her way onto a fishing boat to follow what might be the very last migration of the Arctic Tern from pole to pole. Host Steve Curwood speaks with author Charlotte McConaghy about her masterful debut work of environmental fiction. (15:30)

BirdNote®: What In The World Is A Hoopoe?

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

The soft, modest hoots of the Hoopoe signal a bird so distinctive and fabled that it figures in mythologies of Arabic, Greek, Persian, Egyptian and other cultures. Birdnote’s Michael Stein has more about the bird as a cultural icon. (02:02)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

201204 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood and Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Chibeze Ezekiel, Frances Moore Lappé, Charlotte McConaghy

REPORTERS: Jes Burns, Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

The pandemic has Americans lining up around the block at foodbanks.

MOORE: We have developed a system that is one of the most unfair, unequal in the world and we can do better. We are the world’s largest food exporter and we produce so much food every day, vastly more than Americans need to eat and yet we still have this hunger.

CURWOOD: Also, a novelist provokes us to ask hard questions as the climate changes.

MCCONAGHY: Fiction has the ability to help people emotionally access what's going on. We need science more than anything but I think sometimes fiction can really support science as a way for people to put themselves deep in the heart of the problem and really feel what it's gonna be like in this world if we don't do something.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

The Pandemic And American Hunger

As unemployment surged after a major shutdown of businesses during the coronavirus, pandemic food banks became understaffed and overwhelmed by demand. (Photo: Chief Petty Officer Sarah Foster, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The coronavirus pandemic has exposed a number of fault lines in America, from skepticism and outright rejection of proven science to the perilous economic state of many households. The long lines at food banks are testimony of growing food insecurity in the US, which was already at ten percent of households before the pandemic, and more and more people without a job now struggle to feed their families. But the US produces plenty of food, says Frances Moore Lappé. She’s the author of Diet for a Small Planet and founder of the Small Planet Institute and joins us now. Frankie, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MOORE: Thank you, I am delighted to be back to my favorite radio show.

CURWOOD: Thank you. So here we are in the holiday season and this past Thanksgiving, we saw pictures of people waiting, five or more hours in line at food banks. What's going on here?

MOORE: It's is tragic, Steve and it is totally needless. I just saw that number 4 billion meals being distributed. And it is such a wakeup call for all of us that we have developed a system that is one of the most unfair unequal in the world. And we can do better. So this hunger that we're seeing exposed is something that is hidden most of the time, we are the world's largest food exporter, and we produce so much food every day, vastly more than Americans need to eat and yet we still have this hunger.

CURWOOD: So Frankie, who are these people in line at the food bank? This isn't just the poorest of the poor, I gather?

MOORE: No, I think what it shows is that we have so many people living at the edge. There are something like over 40 million Americans who make no more than $15 an hour. And we've seen these numbers, like most families don't have enough savings to get them by any kind of emergency and that need not be. We do have a safety net, it’s not adequate it's not nearly what it is and other industrial countries. There's so many who aren't, you know, needing to take advantage of that safety net, who still are so vulnerable to economic turndown.

CURWOOD: Yeah, so the folks of the poorest of the poor, presumably have gotten a range with the food stamp program and such to take care of the bulk of their needs but in this pandemic, they're a whole bunch of folks who never thought that they would have to go to a food bank, I guess?

MOORE: Absolutely. Absolutely.

CURWOOD: What are the psychological effects of hunger?

MOORE: Well, my core understanding of our society and in general people is that we, you know, we hear the expression, seeing is believing but actually for human beings, believing is seeing. And the frame we've been taught deliberately, very consciously taught to see our economy as basically fair, free, free, free, and fair. And from that premise, then if you're not doing well, if you're really struggling, what does that say to you that well, you might feel shame, because you're not succeeding. First of all, no, market is free., every market has rules. Unfortunately, in our market, we've come to accept something driven primarily by one rule, and that is do what brings highest return to those people already who are wealthy, until we reach such income inequality, that the last time I looked, we ranked in inequality of income between Argentina and Haiti, worse than more than 100 countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to push 17 million Americans more into food insecurity this year, raising the total to 54 million. In 2020, about 7 million more Americans enrolled in the Federal Supplemental Assistance Program. (Photo: Brendan Mackie, National Guard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So the family that's in line in their vehicle for food at a food bank, and by the way, you see a lot of vehicles there that wouldn't be owned by the poorest of the poor. The psychological effect on them is essentially they've somehow failed. If they're hungry, they're doing something wrong. Is that what you're telling me?

MOORE: Well, I think, yes, I, you know, I know that it's not conscious for most of us. But I do think that there is this premise that if you try you make it in our economy, because we have this great system, we have this free market economy in which everybody can have a chance. In fact, I'd love to harken back to the decade in which I was born in the 40s. Franklin Roosevelt said that the liberty of democracy is not free if we tolerate this concentration of economic power, and he said that political rights alone can't make a democracy. We have to have economic rights and he wanted an economic Bill of Rights. He understood that the preamble to our Constitution it says that our purpose as a nation is to promote the general welfare, not just for everybody to free to do their own thing. And when FDR stepped up, we had been decades in which my generation from the 40s to the 70s, when my children were born that generation, every income class, it's real family earnings doubled, but the poorest gained the most. But my children who were born in the 70s, that generation is a different tale, the wealth just rushed to the top. So my point, Steve, is that experiencing this moment exposed, so much right in our eyes but the COVID pandemic is something that in the past we have been able to avoid with real leadership that under understood that we have to set fair rules to allow our political goals to be met for the general welfare.

CURWOOD: Now, not only are people food insecure in this country, but around the world, there's a lot of food insecurity, yet you write that there is plenty of food for global population. So, as we seem to grow more food than ever before, what's going wrong?

MOORE: Well, yes, this is what woke me up. You know, this was my, in my 20s, when I said, “Why is there such hunger in the world?” Because we were being told then that there just wasn't enough food that we were over running the earth, too many people. So I checked it out. And you're absolutely right. There is more than enough food produced in the world today to make us all have plenty, plenty. And you know what, since I wrote my first book, Diet for a Small Planet, we now per person in the world, we have one fifth more food than we did then produced for every person on earth. And yet we still have one in five of young children are stunted, stunted. And there's a lifelong impact from lack of good nutrition and poor water supplies. So we are still challenged from going to the roots of hunger, which is to me democracy itself.

Frances Moore Lappé is author of Diet for a Small Planet. She founded The Small Planet Institute, which focuses social solutions to the environment, hunger and politics through living democracy. (Photo: Courtesy of The Small Planet Institute)

CURWOOD: Well, let's talk about how food insecurity around the world but especially as it's been revealed during the pandemic here in the United States, how does that affect the dignity of people? How does it affect our Democracy, to have so many people online trying to get food from a food bank?

MOORE: Without a fair distribution of income, fair opportunity, it is almost impossible for me to imagine how we can have such inequality and have a genuine political democracy. Now, this last election, the billions that were spent, were record spending and most Americans are very against that. The vast majority of us, three quarters of us see that money has too much influence in politics. And so that is the link there we get it that highly concentrated wealth infects our democracy, and therefore it doesn't serve the majority.

CURWOOD: So some people say food is love. What are the long lines at the food banks tell you about what's going on in families and in our society?

MOORE: It tells me that we've not been able fully to accept that when our constitution calls us to promote the general welfare, that that's premised on the idea of love that we all feel connected to one another, that we are participants. So let's listen to who we really are. Human beings need power, meaning and connection and let's use those needs to get at the roots of hunger.

CURWOOD: Francis Moore Lappé is author of Diet for a Small Planet and founder of the Small Planet Institute. Frankie, thanks so much for taking the time.

MOORE: Thank you, Steve. A great pleasure.

Related links:

- Mother Jones | “‘These Photos Show the Staggering Food Bank Lines Across America”

- The New York Times | “‘Just Because I Have a Car Doesn’t Mean I Have Enough Money to Buy Food”

- CNN | “‘Thousands Line up for Groceries at Dallas Food Bank”

- Learn more about The Small Planet Institute

- Check out Frances Moore Lappé’s newest book Daring Democracy

[MUSIC: Norah Jones, “The Long Day Is Over” on Come Away With Me, by Jesse Harris, Norah Jones, Blue Note Records]

Beyond The Headlines

Newly named Wilton Cardinal Gregory is the Archbishop of Washington, DC.(Photo: DC-wiki-2020, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: It's time now for look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with environmental health news. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And he's on the line from Atlanta, Georgia. Hi, Peter. What do you got for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Jenni and Atlanta, Georgia is where we start because the former Catholic Archbishop of Atlanta Wilton Gregory, then moved to Washington to be Archbishop there, was just raised by the pope to be Wilton, Cardinal Gregory, the first US African American Cardinal. He's also one of the most active and vociferous Cardinals on climate change. And on the Pope's encyclical of 2015. Laudato Si', On Care For Our Common Home, which was all about the environment.

DOERING: Well, Peter, that sounds like good news. And I think you could say that doing nothing about climate change would be a cardinal sin.

DYKSTRA: It would be a cardinal sin, it would be a pretty good pun, congratulations, Jenni, and it would also be the past mode of inaction for the church. Cardinal Gregory has also been very, very active in welcoming LGBTQ Catholics into the church. He led the church's zero tolerance policy in response to sex abuse, which of course has plagued the Catholic Church for the last few decades. And in addition to climate change, he's been very much in line with the Pope's encyclical about using the power and scope of the church to help clean up the earth.

Coat of Arms of the U.S. Cardinal Wilton Daniel Gregory, Archbishop of Washington. (Photo: SajoR, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5)

DOERING: Hey, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Georgia's gonna stay on our minds. Jenni, because of the bigger political issue of the day in the minds of many Americans; are the two senate runoff elections coming up that could decide whether the republicans or democrats control the Senate. There are 16 Superfund sites, they're threatened by extreme weather linked to climate change. Three particular sites, as listed by Inside Climate News are along the coastline, along a beautiful stretch of coastline in Southeast Georgia, near the town of Brunswick. One of them is a former wood treatment site. The second one is a landfill for sewage treatment plants. The third one is a chemical factory. Near that site, bottlenose dolphins have been found to have high levels of toxic chemicals in their tissue. Near the landfill treatment site, there are shellfish found with five times the permissible level of toxic chemicals. They're in need of cleanup, they've been on the Superfund list for quite a while. The other sites in Georgia, none of them by the way, real near Atlanta where I am. But in other parts of the state, there are all manner of toxic facilities, coal ash sites from power plants other factories. Atlanta and Georgia, I'm happy to say at least are not as much of a mess as my ancestral home up in New Jersey.

DOERING: Well, that all sounds like multiple disasters waiting to happen, Peter. So what's in the history calendar this week?

DYKSTRA: December 12 1980, Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Cleanup and Liability Act, also known by one of those horrible government acronyms CERCLA. But CERCLA, of course is even better known by its high school yearbook nickname, Superfund. So back to Superfund, there are over 1000 sites across the country that remain on the cleanup list.

DOERING: Well gee, Peter, why are they still on the cleanup list decades later?

The Shpack Landfill Superfund Site in Norton, Massachusetts. (Photo: Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: For the most part, not much has happened at all in the last four years, but you could also argue that not that much has happened in the 40 years since Superfund came into being. Most of the delay is over litigation about whether the government pays for cleanup, whether the industries that polluted pay for the cleanup, or in some cases, industries that bought out the polluted sites pay for the cleanup. Bottom line is that it's literally a mess.

DOERING: Thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Peter we'll talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Jenni, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

DOERING: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website. LOE.org.

Related links:

- InsideClimateNews.org | “The First African American Cardinal is a Climate Change Leader”

- InsideClimateNews.org | “In Georgia, 16 Superfund Sites Are Threatened by Extreme Weather Linked to Climate Change”

- HazardousWasteExperts.com | “What is CERCLA – and why is it important?”

[MUSIC: Gerhard Meinl’s Tuba Sextet, “Meltdown” on Tuba! A Six-Tuba Musical Romp, by Jonathon Sass, Angel Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – How scientific research is another victim of the pandemic.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gerhard Meinl’s Tuba Sextet, “Milonga” on Tuba! A Six-Tuba Musical Romp, by Enrique Crespo, Angel Records]

Ghanaian Climate Leader Wins Goldman Prize

Chibeze Ezekiel giving a talk on climate change to schoolchildren in Ekumfi for his “Children for Climate Action” program. (Credit: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

In 2013, the government in Ghana planned to build a 700 MegaWatt coal power plant in the coastal fishing community of Aboana. But for Ghanaian environmental activist Chibeze Ezekiel the risk of a coal fired power plant was too high. He’d seen how coal had polluted other African communities and was worried it would worsen climate change. So, Mr. Ezekiel organized a grassroots youth campaign and successfully convinced the government to drop coal and invest instead in renewable energy. For his work Chibeze Ezekiel received this year’s Goldman Environmental Prize for Africa. And he joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Chee!

EZEKIEL: Thank you very much, Jenni for this opportunity.

DOERING: So, talking with other youth and thinking about climate change yourself, what really compels you to get involved in this? Like, why is climate change something that you really care about, and you've worked so hard to address?

EZEKIEL: When I got introduced to climate change in 2009, because it was basically a new concept to me, it was more about reading around it, hearing people's story, I was hearing about climate impact. But because I didn't get that physical experience on what it means to suffer from climate impact, I didn't really appreciate the magnitude of what climate change can do, until had a chance to visit one community, the fishing community, in south part of Ghana. And where the sea had actually submerged a whole community. So for me, that was when I started thinking that wow, so this climate change is really serious. I mean, I thought that was just something I was reading on the internet. So that actually made me realize that no, this is something happened in Ghana, not in any other part of Africa or the world, but close to my in my country. So then that's actually ignited, you know, the passion to start the advocacy that we need to treat this as an issue of emergency. And make sure we try to fight, you know, its impact until it becomes extremely devastating.

DOERING: Could you just describe for us this region where the Ekumfi coal plant would have gone that you helped to organize to stop? What's it like there?

EZEKIEL: Yes, Ekumfi is in the central region of Ghana. It is not a very developed area. People are still living in abject poverty with limited social amenities. So there are seven small, small communities within Ekumfi. We actually knew that our task was a very big one. So we certainly have to be very strategic if we have to win this battle. So to begin with, we adopted what I want to call the submarine approach. In other words, we did a lot of underground work, without coming out without making noise. So we went to the community, Ekumfi, and spent about three or four days with the people in our community. We spoke to the chiefs, we spoke to the elders, the woman groups, the youth groups, the fisher folks to get their view of the coal plant. And fortunately for us, we some of them, I mean, publicly, you know, openly told us that they're not in support of the coal plants because of similar experiences they had or heard in other communities. So again, we started mobilizing.

Children in the coastal fishing community of Aboana, Ghana, where the 700-megawatt coal-fired power plant was proposed to be built. (Credit: Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: I know that Ghana, it does actually enjoy one of the highest rates of access to electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa at over 80% of its citizens having electricity, but there are these frequent supply shortages. So, I can imagine how compelling the idea of a giant new coal plant would be to so many who are concerned about electricity. How does that kind of conversation play out in the campaign with you convincing decision makers and locals that yes, electricity is important, but there's a better way?

EZEKIEL: At that time, around 2015, Ghana was in a lot of energy crisis. The demand for power was more than government could supply. Indeed, companies were collapsing. Indeed, people were losing their jobs. I mean, we're not having constant energy supply. So at that time, government was under pressure to solve that problem. And we're also due for election in 2016. So every government automatically wouldn't want to lose, they really want to be voted back into office. So the fact that building a coal plant will solve the problem so people can trust them as they vote for them in 2016. The argument we made was, now we are relying on South Africa for coal, which means we don't have control over the source or the raw materials. So the issue of sustainability was not guaranteed. We cannot put our hope in that to create more problems for ourselves. So we said, well, we thought we this we have this sun, you know, this natural sources, you know, in abundance. They are reliable, they are available, the sun keeps shining all the time, the wind is blowing all the time, the sea is always there. And as we've talked about sustainability, their renewable energy or clean energy is better, you know, as compared to putting our hope and our trust in coal which has been imported from South Africa, which we don't have control over. So this way, I made a key argument you made in that regard.

DOERING: And you did in fact, eventually convince Ghana's Environment Minister to halt the construction of the Ekumfi coal plant. What parts of your grassroots, and in fact, your submarine campaign, do you think really convinced the Environment Minister that this wasn't a good idea?

Fishing boats parked in Jamestown, Ghana, a coastal community in Accra. (Credit: Goldman Environmental Prize)

EZEKIEL: You know, campaigning or advocacy is not an issue of emotion or an issue or feelings. If you are fighting government, you want to come up with a very stronger argument, because government needs solution. They want immediate solution. So if you're coming with an alternative, then you have to be more powerful than what government itself was thinking. So using a submarine approach: go low, learn more, do more research, do more engagement, get the right information. So by the time you come out, you know, you're speaking based on fact, based on evidence, and that becomes even a means to influence government to buy into your decision. I believe strongly that our approach worked very well. We are youth group. We don't have the resources. We don't have the muscle, you know, to wrestle with government for years or for months. But we also don't have the money to go to court to challenge government. We don't have a lawyer, you know, we're talking about the grassroot movement, young people. So based on what you have with our limited resources, what can we do to achieve the impacts or the objective that we anticipate? So by the time we came out publicly, I mean it tooks us about five to six months to achieve our end.

DOERING: Wow, that's actually a pretty quick turnaround in terms of campaigns, so congratulations on that success! So instead of the coal plant, to what extent are renewables like wind and solar energy being installed in the Ekumfi region and helping bolster the energy supply?

EZEKIEL: Yes. So even though the pace is quite slow, there has been some effort to develop renewable energy in Ghana. Specifically, I've not sighted any solar plants or any wind plants being put up in Ekumfi. But I am aware that there are communities close to Ekumfi that's have solar farm. Initially, it was 20 megawatt solar farm. And now we have an additional 20 megawatt solar farm by a Chinese company. So we have about 40 megawatt solar farm, you know, a place that is not too far from Ekumfi. But what we are trying to promote is that if at the National Grid, were able to develop renewable energy, then government can even get power to supply, to organize, including those in Ekumfi. At a point, we got to know that Ghana has about 200 islands, which means that those communities are off grid, because it was quite expensive to send to put up transmission lines, or there were two those communities. So in those communities, they're putting up solar mini grids. So those communities today as I speak, have access to electricity. So increasingly, we are having some levels of adoption.

DOERING: So Chi, what are you focusing on now in your activism? What's on the horizon for you?

Ghanaian environmental activist Chibeze Ezekiel recieved the 2020 Goldman Environmental Prize for his clean-energy grassroots campaign. (Credit: Goldman Environmental Prize)

EZEKIEL: We have formed what we call the Youth in Renewable Energy Movement campaign. So there's a whole movement of young people in renewable energy making all the advocacy work, all the campaign, to support governments effort on renewable energy. We're also running a Youth in Climate Action Campaign, where we are building a capacity of young people to participate in Ghana's national adaptation plan processes, as well as the development and now the review of our NDCs in our leading to the implementation. So that does what we are doing now; building our capacity to participate in the decision making process. So eventually, we can all collectively fight, you know, the climate change that we all seek to do

DOERING: Chibeze Ezekiel is a board member of 350 dot org, and the Africa Recipient of the 2020 Goldman Environmental Prize. Thank you so much, Chi.

EZEKIEL: Thank you very much for the opportunity, Jenni.

Related links:

- Goldman Environmental Prize | Learn more about Ezekiel and his campaign

- Goldman Environmental Prize | Chibeze Ezekiel’s Acceptance Speech

- 350Africa.org | Chibeze Ezekiel - Goldman Prize Recipient

[MUSIC: Babatundi Olatunji, “The Beat Of My Drum” on Dance To the Beat Of My Drum by Babatundi Olatunji, Blue Heron Records]

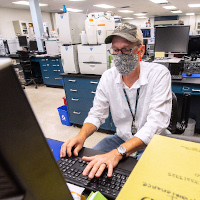

Troubles For Science Research In The Pandemic

To adapt to COVID-19 precautions, many scientific researchers have had to socially distance while at work, if they have been able to continue their research. (Photo: Dennis Schroeder, National Renewable Energy Lab, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: The Coronavirus pandemic has affected nearly every aspect of life and society, including the ways in which some scientific research is conducted. A number of laboratories have had to shut down and funding has become more of a challenge. Oregon Public Broadcasting reporter Jes Burns has the story.

BURNS: During the early days of the pandemic, whether or not you had a backbone could have been the difference between life and death. At least if you were a lab animal.

BRANDER: OSU would let you take care of fish during the shutdown, but invertebrates were not considered to be, I guess, important enough.

BURNS: Not being able to access her lab was a problem for Oregon State University researcher Suzanne Brander. She studies how microplastics and chemical pollutants affect sea life, including the lowly, spineless mice and shrimp that plays a big role in the ocean food web.

BRANDER: And so that's why we decided to move the mice shrimp cultures home and the best place to put them was my basement.

Animated GIF of Oregon State University ecotoxicologist, Susanne Brander. (Photo: Courtesy of Jes Burns)

BURNS: There she cared for them with her kids for several months. By summer, the shrimp were back home on the Corvallis campus. But things were not back to normal, and they still aren't. Fewer researchers can access the lab at the same time and all the workstations have been spaced out. Although this might be a good thing if you weren't next to grad student Catherine Lasdon who counts microplastics in the dissolved intestinal tracts of Oregon rockfish.

LASDON: It smells bad, I'm warning you.

BURNS: But the real concern for Brander is money. Much of her lab's research, staffing and supplies is funded by grants.

BRANDER: It's hard because it's not as if you can ask a funding agency that's giving you a grant for more money. So you have to kind of stretch it out and make it work even though you're missing a three or four month chunk of time.

BURNS: The grant money crunch is also being felt by Oregon Health and Science University's Nicole Bowles, who studies the effects of irregular sleep cycles on cardiac health and firefighters. She thinks money is especially of concern for early career scientists.

BOWLES: As a young investigator who's trying to build my research portfolio, every dollar really really does count.

BURNS: She says senior researchers seem to be more secure.

BOWLES: I've already seen it. I'm thinking about a talk I went to in May and an established researcher, they were able to like flourish during this time. It was like they seem to be writing a paper a week, you know, whereas I'm trying to figure out like, how am I going to make it work?

BURNS: While concerns over funding are widespread, in some cases, the interruption of the research itself is the most acute loss. Every summer, the nonprofit Klamath Bird Observatory monitors migratory bird populations in rural Southern Oregon, using a crew of budding scientists from all over the world. Director John Alexander says when the pandemic hit, they realized something very quickly.

ALEXANDER: We cannot be vectors into rural communities where we do this work.

BURNS: The observatory told their crew to stay home. And consequently, for the first time in 25 years, their bird counts didn't happen.

Animated GIF of Oregon Health and Science University occupational health researcher, Nicole Bowles. (Photo: Courtesy of Jes Burns)

STEVENS: It's a huge setback when you have these long term data sets to miss a year of data.

BURNS: Science Director Jamie Stevens says the stakes are high. A recent study found that the US and Canada had lost 3 billion birds in the past 50 years. And the observatories long term data provide the backbone of policy changes that could help reverse the trend.

STEVENS: It's just incredibly urgent right now. So of all the things that put on, put on pause for a year. It's just all getting a little behind when we don't have time to get behind. We need to be taking actions like a decade ago.

BURNS: Scientists say in the institutions they work for are figuring out how to push the research forward in a pandemic world. Plastics researcher Brander says she feels like she's successfully ridden out the first wave.

BRANDER: For now we're, we're okay. It's not great. But we can manage.

BURNS: But with record surge in cases, she's concerned about the future.

BRANDER: I'm terrified about what things are going to look like after Thanksgiving, especially seeing and hearing about the numbers of people who are planning on still traveling or having family from out of town.

BURNS: So far, Oregon State is allowing the labs to remain open. But if case counts get much higher, Brander fears another complete shutdown of her lab could be coming. I'm Jes Burns reporting.

CURWOOD: Her story comes to us courtesy of Oregon Public Broadcasting

Related link:

See more about this story at the Oregon Public Broadcasting website

[MUSIC: Robert Plant, “Silver Rider” on Band Of Joy, by Zachary Micheletti, Mimi Parker, George Sparhawk, Rounder Records]

The Road To Darwin

A sunset off the highway on the road to Darwin, Australia. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

DOERING: Australia is full of wonderful and strange animals. From salt water crocodiles and turtles that breathe through their behinds to the duck billed platypus, a mammal that lays eggs. For all its oddities the island country isn’t home to any native big cats. But rumors of sightings have circulated since the 1800s and Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, recently had a close encounter of his own.

The Road to Darwin

Driving north on the Stewart Highway, (two lanes straight as an arrow) the tarmac belongs to the Road Trains. Three and four trailers 120 metric tons each one, cruising at 130 clicks, cab the size of a locomotive – they are of a speed and configuration making it impossible for a Road Train to turn. Valerie and me, we give Road Trains the full width of the road, pulling halfway off onto the dirt shoulder as soon as we spot them, deliberately sending up a cloud of dust to let them know.

They blare their horns and wave and we wave back. The shockwave rattling the camper van as they push on through.

Karlu Karlu, also known as the Devils Marbles, a collection of gigantic stone boulders seen as one of the most recognized symbols of the Australian Outback. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The sun is careening towards the horizon, and the distant mountains still no closer than they were this morning in this vast and timeless place. Nothing not even a Road Train will travel here in the dark. Cow country. Unfenced. The cows wander out into the middle of the highway... At night, you won’t see them. We start looking for a turnout.

Soon enough we find our camping place, a clearing beside the road. We lay back. Look up. An unfamiliar sky unfolds; the Southern Cross with its blazing stars the one thing unmistakable.

In the morning up with the sun we push on, finally stopping for lunch at the marker for the Tropic of Capricorn. Just to say we did. And take pictures. Just to prove it. And on our way again.

Not ten minutes after, Valerie in a quiet voice says, “Look… ”

Mark Seth Lender stands at a marker of the Tropic of Capricorn. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Unmistakable as that Southern Cross, a black panther crossing the road.

He glances at us - barely - as if we are a familiar sight.

Doesn’t run.

Doesn’t grant us a second look.

And in his casual cat-like cadence slips into the underbrush and turns, parallel to the road for a dozen meters more -

And disappears.

We have seen a thing of legend. Rumored. Unconfirmed. Object of conjecture. Of ridicule. And yet, all that a panther is rare to the point of disbelief he treated us like something unremarkable and, of no importance.

Things come. Things go. Like Road Trains and dust. Black panthers remain. To them, we and our age of industrial scale and speed, we are the creatures of myth, the ones who do not exist. Or if we do, in their timeless view? A passing fancy.

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s Website

- Read the Field Note for this essay

- Mark’s fieldwork is arranged by Destination: Wildlife

[MUSIC: Adrian Legg, “Paddy Goes To Nashville” on Mrs. Crowe’s Blue Waltz, by Adrian Legg, Relativity Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A dystopian novel with a message of hope for vanishing species. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Los Gringos, “Bolivia” by Cedar Walton on unreleased demo]

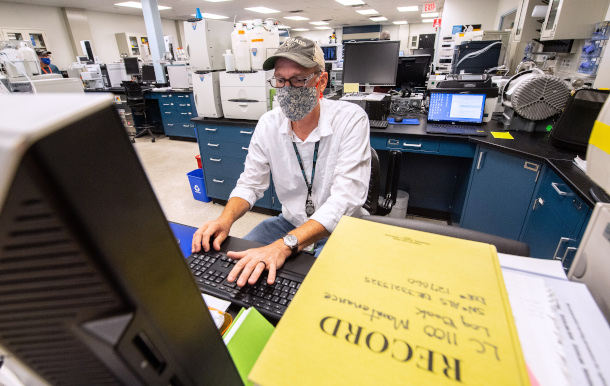

Migrations: A Powerful Novel About A World Losing Life

The Arctic tern has the longest migration route out of any bird. Every year, it flies from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back. (Photo: Ed Dunens, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Charlotte McConaghy has written a debut novel Migrations that is attracting a lot of attention for its brilliant writing and core topic, climate disruption. The novel is set in a future in which many of the animals we know and love, like polar bears and the great apes are extinct and the oceans are running out of fish. Yet, the Arctic Tern, a bird known for having the world’s longest migration, remains. In years yet to come one woman follows what might be the very last migration of Arctic Terns from pole to pole. But this work of fiction is about a voyage of discovery far beyond the birds. Author Charlotte McConaghy joins me now from her home in Australia. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MCCONAGHY: Thank you very much for having me. It's a pleasure.

CURWOOD: Our pleasure. So tell me, where did the idea for this novel come from?

MCCONAGHY: Well, it's tricky for me to pinpoint it because it was one of those things that came in a lot of different pieces. It was quite fragmented. But I wanted to engage with my kind of concern around the climate crisis. But I didn't know how, because it felt just far too big. So I sort of parked that notion. And I went traveling, and I wanted to explore the UK, which is where my ancestors are from. And I started noticing all the beautiful birds, the migrating birds over there, particularly the greylag geese, which I learned about while I was in Iceland. And I just became really fascinated with where they must be flying and these incredible journeys that were going on. And I started thinking about the idea that wouldn't it be amazing if we could follow them and experience those, those migrations with them? So I think that's where that initial spark of an idea of this woman who's following the last migration of the Arctic tern.

CURWOOD: So tell me, I mean, all the animals on this planet why the Arctic tern?

MCCONAGHY: Well, I didn't know initially, which bird she would be following. So I did, I was doing a lot of research into a lot of different birds. And the moment I came across the Arctic tern, I knew it was the one - I fell in love with it. It has the longest migration of any animal in the world, from the Arctic to the Antarctic, and then back again within a year. And because it lives for about 30 years, over the course of its lifespan, it will fly the equivalent distance of to the moon and back three times, which I just thought was absolutely beautiful and kind of amazing that such tiny creatures could go so far for survival, and we're making this journey more difficult for them every year. So they sort of became a metaphor for courage, the courage that Franny would need to take on her journey, and I think she takes a lot apart from them. If they can do it, then she can, too.

CURWOOD: So recently, we've been learning quite a lot about the emotional toll that climate anxiety and climate grief have for so many of us. How do you think this affects Franny, the protagonist of your novel?

MCCONAGHY: Quite severely, I think, one of the reasons that I wanted her to be such a migratory creature herself, and such a wild creature, and so similar to the animals that she loves, is because I wanted her to have a really deep connection to the natural world, which would allow her to be a great mouthpiece for her to experience the loss of this wildlife and the natural world that's disappearing piece by piece, just as we're losing it. I think she suffers that grief, perhaps more intensely than the rest of us do, which is why she's so driven to do something about it.

Migrations tells the story of one woman who wants more than anything to follow what might be the very last migration of the Arctic tern. (Image: Flatiron Books)

CURWOOD: Yeah she's willing to risk her life to follow this passion.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, that's right.

CURWOOD: One might say in some respects, climate change is perhaps changing everything. I mean, it just has so many impacts on the way that we're living now. But your character Franny is looking at the human aspects on the climate largely through their effects on animals. So what is it do you think about animals that so resonates with Franny?

MCCONAGHY: I think, I think because she grew up without a family, she made a family of the wild creatures around her and the natural spaces. So they became a kind of home for her when she didn't have a normal home. And they became her loved ones when she didn't have anyone else to cling to. And so I think a big part of her is bound to these creatures. And I think also one of the things that originally was an inspiration for me was growing up, I really loved Celtic mythology and the myth of the selkie, which is the story of seals that can shed their seal skin and become humans. And they can, the tragedy of the selkie is that they can fall in love and get married and have children but they'll always be bound to the ocean. And this is something that kind of plays into Franny and her character. She says, at one point in the book, it's not fair to be a creature who is able to love but unable to stay. And so I think that that is also part of her creaturelyness, and this idea that she's not, she doesn't subscribe to a lot of societal values. She has no ambition. She doesn't want wealth. She is really just living in the moment, in a way that I think we all would love to be able to.

CURWOOD: Mm hmm. And she loves water or she certainly spends a lot of time in and around and above water.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, she absolutely does. And I think that's another element of that selkie myth coming in. I've always loved the ocean, there's something very mysterious and frightening and wonderful about it. I guess it's the most important part of our planet, really, because we're the only planet that has ocean which makes it a habitable planet for us. So there's something kind of immense and important about the ocean. I hate the idea of it being pillaged for our benefit.

CURWOOD: And of course, Franny's quite concerned about, shall we say, overfishing?

MCCONAGHY: She is? Absolutely, yeah, it's a real problem for us. And in the world of the book, it's even more of a problem. And so there's that terrible conflict for her that she has to talk her way onto a fishing boat. And it's the only way that she's going to be able to fulfill her journey. But it's sort of really gets under her skin. She hates it, because she's so anti fishing. But I think that's one of the things that this book is about it. It's about overcoming our judgement of the other side of this as this big schism in the world, I think, between conservation and fishing and farming. And, and one of the things that this book, I think, is trying to say is that we need to be able to communicate and not judge each other in order to understand each other and actually try to find ways to support each other to move beyond the employment the way it is now and make it sustainable for the future.

CURWOOD: In other words, we're all in this thing together.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, that's exactly right. Yep.

CURWOOD: So I guess it was Camus, who said, if you want to be a philosopher, write novels, maybe you took that to heart because at one point, you start, you have this discussion about whether people should work to save, quote, important animals, the ones that benefit societies versus working to save everything that seems to be slipping away from our ecosystem. And Franny is not happy that people would even think about making this choice. I think she says, and let me quote here, it's page 209: "What of the animals that exist purely to exist because millions of years of evolution have carved them into miraculous being?" So talk to me about this discussion and why you decided to include it in this book.

A baby Arctic tern. (Photo: Gregory Smith, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, I think this really strikes to the heart of what the book is about, actually. It really upset me to think about the fact that in a dire future, we would only be focused on saving the animals that provide us with some measure of survival, the ones who offer us something. So at this conservation base in the book, they're putting most of their resources into saving the pollinators because they're an integral to our food sources. But yeah, as you read, Franny voices something that I found really tragic myself and I struggle. I know that there's practicalities that need to be taken into account, but it seems immensely unfair, the tragedy of leaving all the rest of the animals to go extinct. You know, it's not their fault that they can't survive. It's our fault. And I think I realized that by writing this book, I was trying to remove humans from the center of all things, trying to point out that we are not the only creatures on this planet that have a right to be here, and that deserve survival. And we shouldn't be behaving as though we are. I think, in a way, it's a love letter to animals, not because of what they offer us. But just because they're beautiful in their own right. And we would have a much poorer world without them. Biodiversity is key, but on a purely emotional level, we will have such immense loss if we let go of the animals.

CURWOOD: It makes me wonder if they could get together and let us go, would they make that choice?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, I think they would if they could, although there are a lot more compassionate than we are, I think.

CURWOOD: In that same section of your story, you also have a scientist saying that birds should be contained and stopped from migrating as a way to save them. And yet, the husband of your main character here claims that migration is well, it's just part of being a bird. Talk to us about these dueling ideas and how this discussion made it into the book.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, well, this was me trying to put myself in the headspace of the scientists and conservationists who are having to figure out how to save these animals, and really trying to imagine what we need to be doing. What do you do if you have an animal that is instinct bound to go on this epic migration in order to find food and breeding grounds, but the journey itself isn't survivable for them? Do you contain them to feed them and keep them alive? Do you force them to to adapt? Or is our involvement in their existence part of the problem that got us into this mess in the first place? Are we having too much of an impact on them? And should we just leave them alone? I don't really know what the answer is. And I think it's clear in the book because there's this ongoing discussion. I do think it's crucial for us to save critically endangered animals from the planet that we made too hard for them. You know, that's the least we can do. But there's something that sits very wrong for me in trying to change their fundamental natures, and the instincts that have led them through those millions of years of evolution. I find it heartbreaking thinking of caging birds.

CURWOOD: And don't imagine you think much of zoos then.

MCCONAGHY: I struggle with zoos, I don't like them. I like it when they use their resources for conservation efforts. But I don't visit them because I find it too sad.

CURWOOD: So the title of your book is Migrations. So what does the theme of migration mean for you in writing this book?

MCCONAGHY: Well, it was initially just about the birds. As I said, I was traveling around the UK and looking for a sense of roots and history and belonging. And I became fascinated with the gorgeous birds that I could see. I think I was fascinated with the idea of movement for survival, and what that might mean for humans, because it often means the same for humans. But I wanted to explore a character who had a kind of driving force inside her, and instinct like the birds for movement as survival, and yet, it was more of an emotional survival than a physical one. And I knew that pretty quickly, the kind of woman who would follow these birds would have to be a fairly special person, she started to form into this wild creature in my mind, who never stops moving, always roaming. And this impacts her relationships quite badly. But it's a compulsion of sorts like it is for the animals, she's searching for where she belongs. And I guess that kind of started bringing up the idea of people who don't know where they belong. And that can certainly be true of settler societies and migrant families, they can often feel a bit rootless, I think. Franny is kind of straddling these two worlds, one that belongs to the people who stayed and abound to their homes, and then one that belongs to the people who left, and perhaps maybe lost that sense of home. I think that's the complexity of migration for people.

Charlotte McConaghy is the author of Migrations. She lives in Sydney, Australia. (Photo: Emma Daniels)

CURWOOD: Now, your story has a lot of destruction, a lot of loneliness. And the impact of human activities is apparent on many of the pages of this book yet. Somehow, it's fair to come away from it with a sense of hope. So talk to me about hope and, and how is it that you're able to cast a spell of hope in such a dark tale as this one.

MCCONAGHY: It wasn't easy to be honest. I'm an optimist at heart. I couldn't live if I didn't think there was hope. But all joy in life would be gone for me. But writing this was one of the most difficult things I've ever done, it took me to some very dark places, and I often felt lost in them. So I would stop and I'd go outside. And I think even without realizing it, I'd be taking nourishment from the little pieces of the natural world around me that I could find, the birds that I spotted walking in trees, even if there are only a few. I'm, city bound, so it was not always easy to find these little pockets of wildness. But you can do it if you're looking for them. And I read a lot of Mary Oliver poetry, which is all about our connection to nature and how it can feed our souls. And that would kind of inspire me to look around and see the truth of the fact that there's so much we haven't yet lost. That's what kept me going. I think we're saturated by bad news these days. It comes at us from every angle, and it's easy to become apathetic or to give up. But now is not the time to give up. It's the opposite. It's the time to fight. And it was really important to me that this book be about hope more than anything, because hope is energizing, it leads to action. And that's what we really need. I think in some ways, the book is a battle cry, and it’s reminding myself of that is how I kept going because I was able to see that there's hope everywhere. It's in the kindness and the generosity that we show each other every day. That's the real stuff. And I think that's what we need to be feeding.

CURWOOD: Charlotte McConaghy is the author of the novel Migrations. Charlotte thanks so much for taking time with us today.

MCCONAGHY: Thank you so much for having me. It's been lovely to chat.

Related links:

- Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy

- More on Charlotte McConaghy

BirdNote®: What In The World Is A Hoopoe?

The Hoopoe’s raised crest contributes to its distinctive appearance. (Photo: Nash Chou, Creative Commons)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

DOERING: From the epic migration of the Arctic Tern we take a look now at a far less ambitious migrant, the Hoopoe which travels between Britain in the summer and northern Africa in the winter. BirdNote’s Michael Stein has more about the bird as a cultural icon.

BirdNote®

What in the World Is a Hoopoe?

Written by Bob Sundstrom

[Hoopoe song http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/6665, 0.44-.48]

These soft, modest hoots signal a bird so distinctive, so fabled, that it is hard to know where to begin its story. So, let's start with the bird's name, Hoopoe [pronounced HOO-poo] — or Hoopo — modeled on its song. [Hoopoe song http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/6665, 0.44-.48]

Its scientific title, too, comes from those mellow hoots: Upupa epops.

Hoopoes are also the only extant members of a unique family of birds: Upupidae [pr: oo-POO-puh-dee] And it's a crazy looking bird: jay-sized, with a long bill like a sandpiper’s. The Hoopoe's head and breast are buffy pink, with a crest it can raise like an Indian headdress. It flies on rounded, boldly zebra-striped wings, fluttering unevenly like a giant butterfly.

The Hoopoe belongs to a unique family of birds that has no other surviving species. (Photo: PeiWen Chang, Creative Commons)

It’s a bird so peculiar — and found through much of the Old World — that it’s caught the eye of humans for eons. The Hoopoe figures in mythologies of Arabic, Greek, Persian, Egyptian, and other cultures. But the bird's fame hasn't gone to its head. In all its oddity, the humble Hoopoe carries on with a minimum of fuss — nesting in tree cavities in Europe and Asia, migrating to the warmth of Africa in winter. [Hoopoe song http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/6665, 0.44-.48]

Never miss an episode of BirdNote, by subscribing to our podcast. Just search for "BirdNote" in your podcast app.

###

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by M. North.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org September 2018 / 2020 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID #: EHOO-01-2015-09-17EHOO-01

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/what-world-hoopoe

DOERING: For pictures of the unusual Hoopoe migrate on over to the Living on Earth website, LOE dot org.

Related links:

- This story on the BirdNote® website

- Watch a Hoopoe parent feeding its chick

- The Hoopoe was mentioned in the Quran

[MUSIC: Abby Rabinovitz, “Tumbadito” on Flute Stories, by Abby Rabinovitz, self-published]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Jay Feinstein, Leah Jablo, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aaron Mok, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Casey Troost, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Destination Wildlife. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth