March 12, 2021

Air Date: March 12, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Warming Planet Slows Ocean Currents

View the page for this story

The climate in North America and Europe depends on tropical heat circulated by a massive system of currents in the Atlantic Ocean. But ice cores and sediments show that the Gulf Stream and other parts of this circulation are now the weakest they have been in more than a thousand years. Stefan Rahmstorf, study co-author and professor of Physics of the Oceans at Potsdam University joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss what slowing Atlantic Ocean currents could mean for the future of life in the region. (08:47)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

For this week’s Beyond the Headlines segment, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood look at Volvo forging ahead with a commitment to go all-electric by 2030. Next, they discuss how smoke from the devastating California wildfires can irritate the lungs, increasing the risk of contracting more severe cases of COVID-19. They then turn back to March 1971, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers undertook an ill-conceived project to channelize the Kissimmee River in Florida. (05:01)

30x30 To Save Species

View the page for this story

President Joe Biden has set an official goal of protecting 30% of US land and ocean for conservation by 2030, on the way to preserving 50% by 2050. This echoes similar pledges by dozens of governments around the globe. Brett Hartl, the Government Affairs Director for the Center for Biological Diversity, joins Host Bobby Bascomb for more. (11:07)

Protecting Badger-Two Medicine And The Grand Canyon

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

Two legislative efforts that were already underway before the Biden Administration came into office are the Badger-Two Medicine Protection Act and the Grand Canyon Protection Act. Both aim to protect the land from oil extraction and uranium mining, as well as the sacred lands and cultures and of the people who have lived there for thousands of years. Host Bobby Bascomb and Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran discuss the status of the legislation in Congress and what’s at stake. (04:45)

Regenerative Farming for Soil Health

View the page for this story

Regenerative agriculture practices that store carbon in the soil are a “win-win-win” for farmers, the economy and the environment, say advocates who claim widespread adoption of no-till, cover cropping, and other practices could perhaps store as much carbon as the global transportation sector emits every year. Nicole Lederer, co-founder of Environmental Entrepreneurs or E2, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the connection between healthy soils, the climate, and the economy. (11:12)

Regenerative Farming In Action

View the page for this story

Regenerative agriculture can help grain farmers and viticulturists alike cope with the chaos climate disruption is bringing to their growing seasons. Rachel McDevitt of StateImpact Pennsylvania reports on the practices that build soil health and help sequester carbon. (06:08)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210312 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Brett Hartl, Nicole Lederer, Stefan Rahmstorf

REPORTERS: Paloma Beltran, Peter Dykstra, Rachel McDevitt

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Climate change is wreaking havoc on Atlantic Ocean currents, including the Gulf Stream.

RAHMSTORF: This is routinely a part of all the climate models. They show a slowdown by the year 2100 between 34% and 45%. is quite dramatic, we're getting dangerously close to the tipping point of that entire circulation system.

CURWOOD: Also, President Biden pledges to protect 30 percent of US land and ocean by 2030.

HARTL: We want to protect sort-of the full diversity of our natural heritage. We don't want to just protect the iconic places, which are really important to protect. But we want to remember that there are biologically rich and important places throughout the country, and many of them still are unprotected.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Warming Planet Slows Ocean Currents

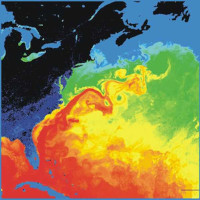

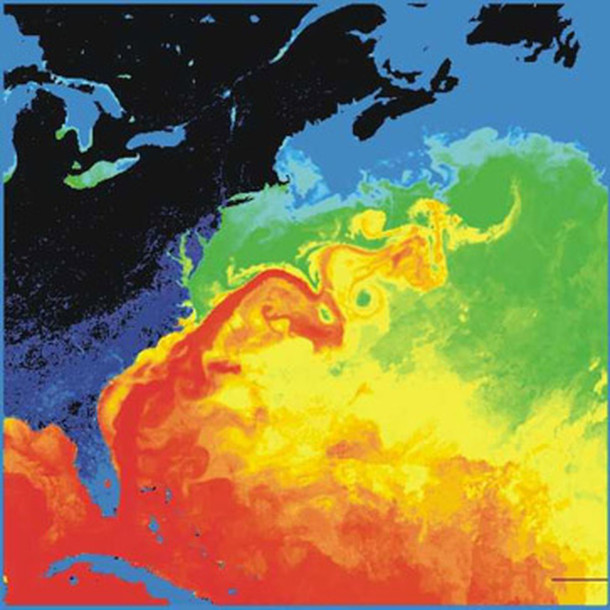

The Gulf Stream is a swift surface current that brings warm waters from the Gulf of Mexico up to the North Atlantic. It is part of a larger system of ocean currents called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). (Photo: NASA)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

There is now more evidence that climate change is slowing down massive Atlantic Ocean currents, including the Gulf Stream that brings warm water north from the tropics along the East coast of the US. This marine conveyer belt is key to weather systems and nutrient transport, and research published in the journal Nature Geoscience finds it’s the weakest it’s been in over a thousand years. Researchers combined data from ice core and ocean sediments going back centuries to show melting in Greenland is disrupting the delicate balance between dense sea water and lighter fresh water that propels the currents. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering asked Stefan Rahmstorf, a Professor at Potsdam University and a study co-author, to explain.

RAHMSTORF: We're talking about the so-called Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. I like to call it Atlantic overturning. It basically consists of surface water that's flowing northward, along the entire Atlantic from the Southern Ocean across the equator, up to the far north to the sub-polar Atlantic, near Greenland, and even right into the Arctic Ocean. And there in the high latitudes these waters sink because they get cold and have a very high density. And they returned south as a cold, deep current. And this works exactly like a central heating system, because warm surface waters are flowing towards the northern Atlantic, and cold, deep waters are flowing away from the North Atlantic and this transports a huge amount of heat, which is released in the sub-polar North Atlantic.

DOERING: Wow. So how does all that heat that's being transported affect what we feel here on the East Coast, in the United States and in Europe?

RAHMSTORF: Well, it actually makes the whole northern hemisphere warmer than the southern hemisphere. And especially the region surrounding the North Atlantic, so including North America especially on the eastern side, and Western Europe.

In Ireland, the Cliffs of Moher overlook the Atlantic Ocean. Western Europe experiences a warmer climate than other regions at a similar latitude due to the warm waters transported Northwards by the Gulf Stream (Photo: Luca Sartoni via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Professor Rahmstorf, how exactly is climate change impacting this overturning circulation?

RAHMSTORF: The reason why global warming is weakening the Atlantic overturning is twofold: first of all, global warming warms the surface waters, and thereby makes them less dense. And secondly, it leads to more freshwater going into the surface ocean, which dilutes the salty sea water and also makes it less dense. And that additional fresh water is coming from an enhanced water cycle in a warmer climate. So more precipitation goes into the northern Atlantic. And it also comes from ice melt. And together these processes inhibit the deepwater formation, and thereby that whole overturning in the Atlantic. And we estimate that since about the 1950s, there has been a slow down by about 15%.

DOERING: And how important is this current?

RAHMSTORF: This circulation is a reason why the northern Atlantic is a particularly productive area with a lot of fish. And I think it's also not fully understood how this change that we're observing now is affecting the marine ecosystems, except we're pretty sure that it does.

DOERING: And do you have any predictions at this point for the future? You know, is this slowdown on a downward trend?

RAHMSTORF: We have not published any particular predictions, but this is routinely a part of all the climate models. They show a slowdown by the year 2100 between 34% and 45%. So about a third to almost a half. That is quite dramatic, and we're coming into an area there where we're getting dangerously close to the tipping point of that entire circulation system.

The Greenland Ice sheet is melting ever faster due to planetary warming, releasing cold, fresh meltwater into the North Atlantic ocean. Scientists worry that this increased influx of fresh water is already changing the dynamics of the AMOC system that is driven by gradients of temperature and salinity. (Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

DOERING: So you mentioned that this Atlantic ocean current is about 15% weaker now than it has been in the past. What kinds of impacts is that already having on life in Europe and North America?

RAHMSTORF: One consequence of that is that in the northern Atlantic, a cold blob has been developing, a kind of area of cooling. And that's the only area on the planet that has cooled in the last 100 years. This is already affecting the weather in Europe. It's somewhat paradoxical to learn that this cold blob out in the Atlantic is causing extreme heat waves in summer in Europe. A further effect of the weakening of the North Atlantic overturning is that it enhances the sea level rise on the North American coast. And that's because any ocean current is linked to a sloping sea surface. The Coriolis force of the earth rotation in the Northern Hemisphere pushes everything to the right for gulf stream flows kind of north along the American coast. The water on the right hand side of the Gulf Stream stands about one meter higher than on the left side, because of that Coriolis force pushing the water to the right. Now, if you weaken that current, the sea level on the American coast comes up. And a further effect that is relevant to North America is that because less heat is transported north into the subpolar Atlantic there's kinda more heat lingering in the subtropical ocean areas of the American coast. And of course, that warm water near the surface is the fuel for tropical cyclones. Tropical cyclones are getting stronger with warming and a part that is already enhanced by that weakening of the North Atlantic overturning.

DOERING: So Professor, there's this 2004 science fiction movie, "The Day After Tomorrow", it's based in part on a scenario where the Gulf Stream grinds to a halt. And that causes global climate chaos and ushers in a new Ice Age. To what extent is there any real life danger of a shutdown of the Gulf Stream?

RAHMSTORF: Well that movie, of course, was first and foremost a Hollywood disaster movie. But it had several grains of truth in it. One of the main things is they had to speed up the whole breakdown of the of the Atlantic overturning dramatically, we would expect this to happen over decades and there it happened over weeks, basically. And the consequences there were also greatly exaggerated, because if you disrupt this Atlantic overturning altogether, then you do get a quite dramatic cooling effect. But you don't get a new ice age or anything of the scale that was shown in that movie. And also, the effects that you get depend a lot on when this happens, like if this were to happen suddenly, it would lead to quite a dramatic cooling in coastal areas at least. But if this current only breaks down 100 years from now, after, say three or four degrees of global warming, then the effect would be a lot less drastic, obviously, because the whole world would already be a lot warmer. It could still lead to real cooling, but it wouldn't definitely be an ice age, that's quite different. But it would be a dramatic disruption of one of the main circulation systems on our planet. I think it would be unforeseeable, but massive effects.

Tidal flooding in downtown Miami, Florida. Disruption to the AMOC system could exacerbate sea level rise on the East Coast of the US. (Photo: B137 via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: So your research shows that the Atlantic overturning actually shut down at some point in the past. When was that, and why do we think that happened?

RAHMSTORF: In earth history, there is clear indication that you see in sediment data and ice core data that this Atlantic overturning has completely collapsed several times. The last one happened again, because of a global warming at the end of the last ice age. There was a major ice melt around the northern Atlantic, and this shut down the Atlantic overturning and plunged the area surrounding the Atlantic back into ice age temperatures. And that cold lasted for about 1,000 years.

DOERING: So Professor, it sounds like this shutting down of this Atlantic overturning could have some pretty severe consequences. What should we do about it?

RAHMSTORF: Well, basically, the short answer is stop global warming. And of course, the world has already agreed to do that in the Paris Agreement 2015. We have to cut global greenhouse gas emissions in half in the next 10 years, and then further down to zero. And if we do that, then I think the risk of reaching a tipping point where we shut down the Atlantic overturning circulation will be extremely small.

BASCOMB: That’s Stefan Rahmstorf, a professor of Physics of the Oceans at Potsdam University, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- Met Office | “What is the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation?”

- Nature Geoscience | “Current Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation Weakest in Last Millennium”

- The Washington Post | “Scientists See Stronger Evidence Of Slowing Atlantic Ocean Circulation, An ‘Achilles’ Heel’ Of The Climate”

- The New York Times | “In the Atlantic Ocean, Subtle Shifts Hint at Dramatic Dangers”

[MUSIC: Yazmin Lacey “Morning Matters”, Own Your Own Records]

Beyond the Headlines

The Volvo V60 Plug-in Hybrid. The Swedish company is planning on going all-electric by 2030. (Photo: Overlaet, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Well, it's time for a look beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter's, an editor with Environmental Health News, ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia, where it's got to be spring there, Peter. I mean, we still have some ice and snow up here but you've got the flowers huh.

DYKSTRA: We got 70 degrees, the flowers are starting, the birds are starting. And of course the legendary Atlanta pine pollen has started, where you can pretty much take a pine pollen shovel and shovel the sidewalks. There can be little pollen drifts everywhere. Not so good if you have hay fever, otherwise, spring is glorious here.

CURWOOD: Okay, so what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, there's some potential good news for clean energy coming out of Sweden, where Volvo has announced their intention to sell electric cars and electric cars only by the year 2030. And that's way before any other carmaker has made a commitment.

CURWOOD: Car makers, we should add though, in the West, I think that the majority of Volvo is now held by a Chinese concern. And China has been really gung ho on electrifying their car fleet.

DYKSTRA: They have and that may help China further dominate the electric car market. But it's also caused a little bit of unease because Volvo is such an iconic brand for Swedes. Having said that, the business side of Volvo has actually done a lot better in recent years under Chinese ownership.

CURWOOD: I imagine there's some folks in Sweden who maybe don't see this development as progress.

DYKSTRA: That's the case. But there's a third nation involved in this, where it's been taken with a little bit of concern. China's powerful economic neighbor, Japan had such success with the hybrid gas electric cars, particularly the Prius from Toyota, that they're way behind on fully electric vehicles.

CURWOOD: Yeah I mean, the Prius first came out in 1997. They sold quite a few of those. I imagine they don't want to let go of that model. But sooner than later, you know, fossil fuel gasoline is not going to be the way to go. What else do you have for us today Peter?

DYKSTRA: Story from California about wildfire smoke more and more reaching into communities. Partly because those communities are reaching more and more into the forest. And wildfire smoke could be getting more toxic to humans, because you're not just burning trees anymore. Homes filled with plastic and other burnables that can create a lot of irritation for lungs.

Specialists conducting a prescribed burn in California. Prescribed burns rid a forest of dead leaves, tree limbs, and other buildup and can help prevent large destructive wildfires. (Photo: Ken-ichi Ueda, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, that's right. Sometimes when you burn plastic, you get chemicals akin to certain kinds of dioxins and that that's not good for us.

DYKSTRA: Well, it's not good for us in another way, because the CDC has studied the effect of wildfire smoke on coronavirus. And what they found is that all of those particulates, all of the irritants, they make it easier for coronavirus to catch on in the lungs.

CURWOOD: It would make for more serious cases and perhaps even more fatalities. It's not a good development. Hey, why don't you take a look now back in history and tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: I'm going to go back 50 years to the spring of 1971, along the month of March. The US Army Corps of Engineers completed an 11 year flood control project to channelize the Kissimmee River, which meanders all the way from Central Florida, around Orlando, south to the Everglades. They took 100 miles of this shallow winding river and turned it into a deep, straight 56 mile ditch. Solving the flood problem, but creating another one.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that's right. So the river of grass, which is another name for the Everglades, that people have used, that that whole ecosystem needs slow running water. So what did they do about that?

Rep. Soto Kayaks Kissimmee River Restoration from SFWMD on Vimeo.

(Video: Restoring the Kissimmee River, SFWMD, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: What happened was pretty remarkable. Scientists and activists and others, persuaded the Army Corps of Engineers that a big mistake had been made. And Congress appropriated money to put the bends back in the river, and the Kissimmee River is now partly restored. And it's made a big difference to its natural flow, and to the prospects of eventually saving the Everglades from all the human intrusion that have put the Everglades this beautiful system into peril.

CURWOOD: This is a case where science really was able to get through with this message and having caused a problem for nature, at least we took some steps to rectify it.

DYKSTRA: That's right.

CURWOOD: Hey, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living On Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Volvo to go completely electric by 2030

- CDC on wildfires and COVID-19

- The Guardian | “California Wildfire Smoke Compared To Vehicle Emissions”

- Kissimmee River Restoration Project

[MUSIC: Miles Davis, “All Blues” on Kind of Blue (Legacy Edition), Columbia Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – New plans to expand the protection of biodiversity as well as native cultures in the United States—stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Miles Davis, “All Blues” on Kind of Blue (Legacy Edition), Columbia Records]

30x30 To Save Species

Around 23% of United States waters are either fully or highly protected, like the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, here seen offshore of California’s Big Sur coastline. The 30 by 30 movement seeks to protect 30% of land and water by 2030, as a steppingstone to protecting 50% of the globe by 2050. (Photo: Robert Schwemmer, CIMS, NOAA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

President Biden has set an official goal of protecting 30% of US land and ocean for conservation by 2030, on the way to preserving 50% by 2050. Dozens of other national governments have also pledged the same goals. Brett Hartl is the Government Affairs Director for the Center for Biological Diversity. He says protecting nature helps address the climate emergency by sequestering carbon. At the same time it fights the extinction crisis while there is still time to conserve critical habitats.

HARTL: We are so quickly exploiting natural resources that we are losing species before we even know what we've lost. And then, you know, even the United States, you know, we still have extinctions. 48 or so species have gone extinct while waiting for protections under the Endangered Species Act, because we just didn't have the resources to protect them all. And they're happening now also, because of climate change, species are going extinct as islands disappear from sea level rise and ecosystem shift. And species on the very tops of mountains have nowhere to go. It's happening. And it's and it's accelerating and getting worse. And if you save 30% of the planets, then maybe those species have a fighting chance.

BASCOMB: So averting mass extinction sounds like a very fine goal. What are the other benefits of protecting land and water?

HARTL: All of these challenges we face are interconnected. So if we protect a large amount of our lands and waters, we're also likely to be averting the climate crisis, we will likely just end up in a better, more sustainable path when it comes to how we exploit natural resources. And then frankly, in the long run, it'll help us create a hopefully a more just and equitable planet, overall, so that we aren't in a mad dash to extract resources in the most reckless way possible. It'll help force us come to grips with a very simple fact, this is a finite planet. And we cannot continue consuming resources as if they are inexhaustible, because the opposite is true. And I'll say perhaps in the most current situation that's playing out still right now, it's important to remember that the COVID 19 pandemic, most likely came from wildlife, and in particular, the exploitation, the unsustainable exploitation of wildlife. And it only happens because we have such an unsustainable relationship with the natural world. So there's many benefits, perhaps most importantly, it is our very survival.

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's a really good point. And can you talk a bit more about how conserving land and water could help in terms of climate change and carbon sequestration?

President Joe Biden has signed dozens of executive orders, including the order that set a federal goal of protecting 30% of US land and ocean for conservation by 2030. (Photo: Adam Schultz, The White House, Flickr, Public Domain)

HARTL: First, we should remember that I think it's about a quarter of the fossil fuels that we consume come from our public lands and water, President Biden in this very same executive order, he put a pause on leasing new oil and gas leasing on public lands and waters to ask that very specific question, what do we need to do to save the climate when it comes to sort of how we deal with fossil fuels on public lands? So it's very much a related question. If we protected more of our public lands, if we manage them more for long term biodiversity for long term carbon sequestration, or we didn't log them all all the time, it would make a huge dent in the climate crisis, because our public lands and waters actually can sequester and lock away large amounts of carbon dioxide if we give them the chance. So that's probably the most direct way that it addresses the climate crisis. But I would say in general, we should always remember that natural ecosystems, whether that's mangroves or seagrass, or natural grasslands, of old growth forests, I don't want to miss a category, but they all have huge potential to sequester carbon, but they can't do it if they are trashed. So by protecting more of these lands, we have a better chance of having nature help us fight climate change, rather than sort of making it worse.

BASCOMB: Well, where does the US stand right now in terms of the amounts of land and water that's currently protected?

HARTL: Right. So there's different categories and levels of protection. According to the US Geological Survey, about 12% of our lands are sort of in the fully protected category, whether it's sort of national park, wilderness, etc. And that's probably about 20, something percent of our oceans are fully protected as national monuments and things like that. If you look at the entire public lands in this country, it's about a third of our land is actually public lands. But many of that, as we as I said earlier, is not protected. It is used for extraction of resources. So it actually does not count towards the goal of achieving 30% protections. But it's important just to note that even if we protected every acre of public lands, they're not distributed evenly in the country. So a lot of them are in Alaska, a lot of them are in the western United States. But we would miss actually huge parts of the country where many, many different species of wildlife and plants are found, that would have no protections. And we would sort of miss the boat because the idea is we want to protect sort of the full diversity of our natural heritage. We don't want to just protect the iconic places which are really important to protect the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Yellowstone, Denali, all these incredible areas, but we want to remember that there are biologically rich and important places throughout the country, and many of them still are unprotected.

This is a canyon in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, designated in 1996 but whose size was reduced by around half by President Trump. President Biden has ordered a review of this reduction, and the monument is expected to re-gain some of its area. (Photo: Bob Wick, Bureau of Land Management, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: So we have an executive order from President Biden for this goal of 30 by 30. But how does the government actually go about making it a reality?

HARTL: That is the $64,000 question. There's sort of two strategies. One, for publicly owned lands for our national forests, our Bureau of Land Management that lands, even our Defense Department lands, we can improve management, we can add additional protections, we can create new national monuments. You know, President Biden can create a monument unilaterally, it is often the first step before things become national parks, which is only something that Congress can do. So obviously, Congress has powers too, they could create additional parks, but we can protect, you know, more of our lands as monuments. Also just strengthen management, so we're not clear cutting everything and drilling everywhere. But we also do have tools to acquire land, we have things like the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which provides almost a billion dollars a year for land acquisition. And there's actually even more money potentially available because over the years, they underfunded and there's actually a surplus left. But we can buy new lands. And it's important for folks as a history lesson to appreciate. If you're in the east, every National Forest, and most of the national parks in the eastern half of the country, were all acquired. They were all purchased back in the Dust Bowl era, they had been private property. And we realized we needed to protect our watersheds and the headwaters of many of our rivers and we purchased them all. So it's not unprecedented to actually acquire land. And the third strategy is the Department of Interior has the ability to establish new wildlife refuges administratively, they can find willing sellers and do conservation easements. And they can create new wildlife refuges, if there's, you know, important wildlife to protect. So we have tools to even expand protected areas beyond just public lands, especially in the East and the Midwest and the South, where the Fish and Wildlife Service can create new refuges. But it's important just to note that we don't want to just see an executive order with nothing more, right? Executive orders can always be reversed by the next president, and we never know when the pendulum is going to shift back the other direction, which is why we want to see that steady progress, you just never know how long an opportunity you have. And if you wait till you're three or four to get really going. It's harder to make that last in the long run, that would just be a lost opportunity.

BASCOMB: Well, you know, there's less than a decade to go to get to 2030. What's your hope for the next few years? What will progress towards this goal look like both in the US and around the world?

Brett Hartl is the Government Affairs Director for the Center for Biological Diversity. (Photo: Brett Hartl)

HARTL: I think in the US progress on 30 by 30, you know, it looks like a couple of things. One, I sincerely hope that President Biden is proactive in creating new national monuments. Historically, what often happens, and this happened with President Clinton, it happened with President Bush, it happened with President Obama, they wait to like the last year in office or something before they they go on a flurry of designating new national monuments as a legacy thing. And that's great. I mean, that's all positive. But my biggest fear is that, you know, all we see is like a report and a strategy. And we sort of procrastinate on our homework. Because it's a big goal. Again, if we're at 12%, now, we need to get to 30. That's several 100 million acres. It would be great if every year President Biden created 10 new national monuments to remind the public every year of how important they are and to try to, you know, space them out all around the United States so that people see them and appreciate them. The longer a monument is around, people are like, wow, that's a huge benefit to us. It increases tourism, it brings in new, you know, interest into our area. I'd say second, you know, we obviously really hope that after the pause on oil and gas leasing is over, that the Biden administration moves to quickly sort of phasing out fossil fuel development on public lands and waters. President Biden said on the campaign, no more drilling on public lands several times. And he's right, this is a polluting industry that's destroying the environment. And it's the primary cause of climate change. And frankly, there's more than enough fossil fuels coming off of other private lands that we just don't need to do this anymore. When I think at the global level, I would just say, there are conversations and international treaties that are discussing this issue right now, including what's called the Convention on Biological Diversity. Unfortunately, the United States is not a party to that treaty. We are, unfortunately one of like three or four countries that never signed that particular treaty, but the rest of the world did and the rest of the world is considering adopting officially the 30 by 30 goal. So we should support that and surely that even if for us, we can't officially sign on to it because we are not in the treaty. But if the world does agree to that goal, the United States can help other countries. We can provide support, technical assistance, financial assistance, to help make that real so that all of these countries benefit from doing the right thing, so that it isn't just on paper.

BASCOMB: Brett Hartl is the Government Affairs Director for the Center for Biological Diversity. Brett, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

HARTL: Thanks for chatting.

Related links:

- The Center for Biological Diversity’s press release on President Biden’s executive order

- National Geographic | “The U.S. Commits to Tripling Its Protected Lands. Here’s How It Could Be Done.”

- Natural Resources Defense Council | “Biden’s Historic Action on 30x30”

[MUSIC: PYÆJN, “Gold Plated”, DeepMatter Records]

Protecting Badger-Two Medicine And The Grand Canyon

The Havasupai live deep inside the Grand Canyon. Havasu Falls is a tourist destination for a lot of Grand Canyon travelers. (Photo: Tripp Gogoi, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, there are countless sites across the country that conservationists say deserve protection as part of President Biden’s goal of thirty by thirty. And Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran has been looking at what might happen next. Hey Paloma!

BELTRAN: Hi Bobby.

BASCOMB: So, what do you have for us?

BELTRAN: Well, I want to tell you about two areas that are up for protection and for both of them it’s not just the land that would be protected but also the culture of the people that have lived there for thousands of years. In both cases Native Americans are working with the government to try to get permanent protection for their land.

The Havasupai have lived in the Grand Canyon since time immemorial. This is an image taken in 1902 of Fannie Baanahmida, a member of the Havasupai Tribe. (Photo: Grand Canyon National Park Museum Collection, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Hmm… that reminds me of the Bears Ears National Monument, native tribes worked with the Obama administration to get the area protected but the Trump administration quickly squashed the plan and made some 85% of it available for oil and gas drilling.

BELTRAN: Right, so now tribes are working through Congressional legislation to get these lands protected, which is much harder for a future president to undo. For example, just outside the Grand Canyon there are roughly 1 million acres of public lands that are potentially open to uranium mining, which threatens both the national park and the drinking water supply for the Havasupai tribe. The reservation is deep inside the Canyon and is accessible only by helicopter, horse or by walking. They’ve been called the guardians of the Grand Canyon before.

BASCOMB: And now it sounds like they need to guard it against uranium mining.

BELTRAN: Yes, they’ve been working with Arizona Representative Raul Grijalva to do just that. In 2019 Mr. Grijalva introduced the Grand Canyon Protection Act. It’s to permanently put an end to uranium mining near the park. The bill passed the House with bipartisan support on February 26, 2021. Now it just needs to pass the Senate.

The Badger-Two Medicine area is 130,000 acres of wilderness. Badger-Two Medicine is named after two crystalline rivers that begin in snowfields and follow along thirty miles of the Continental Divide, Badger Creek (above) and The Two Medicine River. (Photo: Troy Smith, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, it certainly sounds like a good candidate. The Grand Canyon is such a huge draw for tourists and of course an important cultural site. What is the other area you want to tell us about?

BELTRAN: The Badger-Two Medicine area in northwestern Montana. It’s 130,000 acres of rugged snow-capped mountains, forests, and alpine meadows. It’s just south of Glacier National Park and within it are the headwaters of Badger Creek and the Two Medicine River. It’s home to grizzly bears, elk, wolverines and native fish like the cutthroat trout.

BASCOMB: Wow, it sounds stunning!

BELTRAN: Yes! But there’s a lot more to it than just beautiful vistas and habitat. This is the ancestral land of the Blackfeet Nation. And Jon Tester, the Democratic Senator from Montana, introduced a bill in 2020 to permanently protect it as a “cultural heritage area.” This is a first of its kind proposed designation meant to maintain the cultural integrity of the area and could be used as a new type of designation for protecting Native American lands in the future.

BASCOMB: Ahh… so, tell me more about the Blackfeet.

BELTRAN: Well, they’ve lived there for thousands of years. And it’s the backbone to their identity, home to their creation stories and a place of refuge and healing. That’s how it was explained to me by John Murray. He’s the Blackfeet Nation’s Historic Preservation Officer.

MURRAY: We were indigenous to this area. A lot of heroes, legends, the people that were responsible for a lot of the origins of our knowledge system are in the Badger-Two Medicine. A lot of people have conducted vision quests there. The Badger-Two Medicine is very important to us in the sense that we can still interact with nature.

The Badger-Two Medicine area is located between Glacier National Park, the Blackfeet Reservation and the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex. Solenex bought oil and gas drilling rights in the Badger-Two Medicine Area and continues to fight for drilling rights in the courts, despite President Obama cancelling oil and gas leases in the area. (Photo: Courtesy of the Glacier-Two Medicine Alliance)

BELTRAN: The Blackfeet Nation originally stretched from present day North Dakota, west to the Rocky Mountains and North into Canada. But starting in the 1870s the US government began to forcibly take Blackfeet land and allow mining. The Blackfeet have been fighting to protect their land ever since. In the 1980s President Ronald Reagan sold 47 oil and gas leases in the Badger-Two Medicine. Which John Murray says violated treaty rights.

MURRAY: It's the Blackfeet's last refuge. It's relatively wild, it's the way nature is supposed to be, and we've done that over eons of time.

BELTRAN: In 2017 at the end of the Obama administration the Department of the

Interior canceled the remaining oil and gas leases in Badger-Two Medicine but an extraction company which bought oil and gas leases in the area continues to try to fight that ruling in the courts.

BASCOMB: So, what is the status of Senator Tester’s bill to protect the Badger-Two and put an end to this battle about drilling there?

BELTRAN: Well it will need a simple majority vote in Congress to pass and President Biden's signature and Senator Tester is working to get it through.

BASCOMB: Alright, we’ll have to wait to see what comes of it. Thanks Paloma.

BELTRAN: Sure thing Bobby.

Related links:

- Check out the status of the Grand Canyon Centennial Protection Act in Congress

- Grand Canyon Trust | “The Grand Canyon Protection Act: It’s Time”

- Arizona Public Media | “The Grand Canyon Protection Act Passes the House”

- Check out the status of the Badger-Two Medicine Protection Act in Congress

- Read the version of the Badger-Two Medicine Protection Act from June 25, 2020

- Glacier-Two Medicine | “Popping the Hood on the Badger-Two Medicine Protection Act”

- High Country News | “New Bill Would Permanently Protect 130,000 Acres of Montana’s Badger-Two Medicine”

[MUSIC: Pan Flute Crew, “Native American Flute Music with Rain” on Best Spiritual Flute Music Collection]

CURWOOD: Coming up – how the way we grow food can help protect the climate. Regenerative agriculture is ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Dave Brubeck Quartet, “Kathy’s Waltz” on Time Out, SONY BMG ENTERTAINMENT]

Regenerative Farming for Soil Health

A farmer in North Carolina cuts down a cover crop just before planting corn. This blanket of vegetation will reduce erosion, and provide season-long weed protection, moisture retention, and food for microbes in the soil. (Photo: Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Greening energy systems is key to addressing the climate emergency, but science suggests we also need to harness nature to take carbon out of the air and bank it in forests, grasslands, and the soil. A 2017 study in Nature estimated that widespread adoption of so-called regenerative farming could perhaps store as much carbon as all the cars, trucks, ships, trains and planes combined emit every year. And financial support for such farming could help companies offset all of their carbon pollution by 2030. A recent report from Environmental Entrepreneurs or E2 explores how keeping carbon in soils can reward farmers as well. Here to discuss is Nicole Lederer, chair and co-founder of E2. Welcome to Living on Earth!

LEDERER: Thank you very much, Steve.

CURWOOD: So tell me, why do you say that building healthy soils that can hold more carbon is a win-win-win and talk about who you see as the winners here?

LEDERER: Well, the winners are across the board. I have quite a few years behind me in policy advocacy. And it's rare that I have the opportunity to advocate for policy where there are only winners. And the winners here are farmers, the economy broadly and more specifically agricultural technology, and the environment, which benefits in myriad ways, and most importantly, in this context, in the fight against climate change. We're all aware now that simply reducing or even eliminating the global warming emissions that come from our industries, our transportation, our energy generation sectors, that that will not be enough to avoid the worst impacts that are coming our way from climate change. And that, in fact, what we need to do simultaneously is actively and aggressively remove the carbon we have already emitted from the atmosphere and store it. Now, many of the technologic solutions to this are still on the drawing board. They are, in fact unproven. And they will no doubt, at least initially, be extremely expensive. By contrast, the ability of natural systems to remove carbon from the atmosphere and store it in living systems, in the soil, in forests, in prairie, that is a system that has existed that is as old as the earth itself. And that we can maximize, so as to have a significant impact on carbon removal.

This is an example of what healthy soil looks like. This soil was from the use of a diverse set of crops, grasses, and cover crops. (Photo: Catherine Ulitsky, USDA-NRCS, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, what you're talking about here is regenerative agriculture. And one of the techniques you suggest might be useful is the use of cover crops. In other words, growing something on the land when it's not in the crop cycle. And yet, very few farmers now in America seem to be doing that. How do you get the numbers up for cover cropping, and what's in it for farmers?

LEDERER: So regenerative agriculture broadly refers to deploying practices that restore nutrients to the soil as you also harvest crops. And those practices are as old as agriculture itself, and they include low- or no-till practices where instead of removing the crop residue after harvest, you leave it in place and eventually plant into it. It also includes crop rotation, instead of planting the same one or two crops repeatedly on the same fields, and the use of compost. And cover cropping is one of the practices that has been shown to retain much more carbon in the soil, and that avoids leaving vast acreage bare between harvests. There are policies that we can enact that will increase the acreage that uses cover crops, there are currently policies in place that discourage the use of cover cropping.

CURWOOD: Oh, really?

LEDERER: Yes, and many of those have to do with crop insurance policies. There are incentives to not plant crops between your harvested crops currently in USDA policy, and that would be something that would be very useful to change. Also, for all of these practices, anything that involves a change in cultivation practices for farmers involves some degree of risk. Changing from what you do and have done for years to something new, not only involves the risk in terms of experience, but also the potential that you may have to invest in materials or new equipment. And that kind of changeover requires financial support, farmers are not sitting on a big slush fund of money to try new things. So looking at USDA, to channel the funds they distribute for the benefit of farmers and the climate is the goal here.

CURWOOD: Now USDA is famous for providing farmers with the crop insurance that you plant X and if you don't get Y yield, you'll get at least a price support for what you do have. So how does regenerative agriculture resonate with that approach? And how is it dissonant with it?

LEDERER: Well, one of the terrific benefits of regenerative agricultural practices is that it provides a greater degree of security in terms of outcomes, regenerative agriculture and soil health build resilience, in terms of crop resilience against extreme weather, whether that's drought or flooding. Against pests and weeds and all of the challenges that farmers face that they can't control. Building soil health, and increasing soil carbon, which contributes to the soil structure that supports life, is a way of reducing the risk of those crops. Once those risks are reduced, what we're looking to see is a corresponding reduction in the cost of crop insurance. And that is a way to incentivize farmers to take risk reduction methods that would actually reward them financially in reducing the cost of their crop insurance.

CURWOOD: And of course, lower the burden for taxpayers.

LEDERER: Indeed.

Soybean crop pokes through no-till residue from last year’s corn harvest. This corn residue will help with weed management and moisture retention. (Photo: Paige Buck, USDA NRCS Illinois, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So the notion of the soil sequestering carbon is getting a lot of attention in the investment world. A lot of talk about, hey, maybe carbon offsets can be created by farmers who adopt these techniques. Of course, if you're going to try to sell something, you need to measure it. How can you really measure how much carbon is being sequestered in a soil system?

LEDERER: So the arena that you're talking about is generally referred to as agricultural technology, or ag tech. And the way we currently have measured soil carbon is through soil sampling. And that produces a lot of important information, but on a very limited scale. You can only literally take physical samples of soil in a given acre so many times and there are many, many, many acres to sample. So, some of the technologies that are being developed around that involve aerial surveillance by drone or even by satellite to detect the changing carbon content of soil across a much bigger space, a much larger geography real time, and of course, much cheaper than we can do now.

CURWOOD: How reliable is that technology now, though? Today, if you wanted to call a service to either get a satellite pass reading or to have an aerial review of one's land, how reliable is the data that's now currently available?

LEDERER: Well, that data is being generated now. And in the report that E2 released recently, on the topic of agricultural carbon removal, we profile one company that does just that. This is part of the spectrum of products that fall under the heading of precision agriculture, which is a very well developed sector looking at how to produce more efficiently in the ag sector. And we have really advanced technology, allowing farmers to be very specific about where they apply fertilizer, where they apply pesticide or water, etc. And these monitoring technologies are already deployed widely. And they make use of satellite and drone data. So applying that to soil carbon is not a big leap. It's not widely deployed, but it is definitely in the pipeline.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, there's controversy about carbon offset credits from parking it in the soil. In fact, some are worried that trying to put this into the international negotiations could generate pushback. Countries like the US uses as an excuse to not do other things to hit the Paris targets. What do you think?

Farmers Todd and Arliss Nielsen hold up chunks of healthy soil, full of their ryegrass cover crop on their no-till corn field. This no-tillage and cover cropping will build organic matter and may reduce the amount of nitrogen fertilizer they need to apply next season. (Photo: Lynn Betts, NRCS, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

LEDERER: I think it's really important to be sure that if we are going to include in our accounting, that natural systems can be maximized to pull additional carbon out of the atmosphere, we need to be sure that the math is accurate, that we really are reducing atmospheric carbon, not just allowing for current emissions levels to continue while we offset them with reduction methods. What we're looking to do here is go carbon negative. And that is increasingly a goal of companies in the private sector. They're not only looking to lower their emissions, but in some cases to account for and offset past emissions.

CURWOOD: Nicole, these are all fascinating ideas. How do they get implemented in a practical way that works with crops and money?

LEDERER: At the state level, there exists already a number of policies that incentivize low carbon crops. The California cap and trade system is looking to reduce emissions associated with agriculture. And there's also a low carbon fuel standard in California and other states. Now that usually refers to emissions, but if farmers can also claim that in addition to reducing emissions, they've pulled carbon out of the atmosphere, that can create additional financial benefits to farmers. Now, at USDA, at the federal level, there are huge opportunities in revising crop insurance policies. There's also the potential of creating a carbon bank, as has been discussed by USDA already, that might provide low or no interest loans to farmers to deploy these practices. And we are definitely looking to the 2023 Farm Bill to see these policies instituted.

CURWOOD: Nicole Lederer is co-founder of Environmental Entrepreneurs, sometimes called E2. Nicole, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

LEDERER: Thank you very much, Steve. It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- E2 | “Healthy Soils and the Climate Connection: A Path to Economic Recovery on America’s Farms”

- Earth Institute, Columbia University | “Can Soil Help Combat Climate Change?”

- AgFunder News | “Regenerative agriculture is getting more mainstream. But how scalable is it?”

- World Resources Institute | “Regenerative Agriculture: Good for Soil Health, but Limited Potential to Mitigate Climate Change”

[MUSIC: Martin Simpson, “Will This House Be Blessed/The First Cut Is the Deepest” on Live, by John B. Spencer/C. Stevens, Red House Records]

Regenerative Farming In Action

Turnips can be planted on dryland wheat fields as part of cover cropping, a key practice in regenerative agriculture. (Photo: Garrett Duyck / NRCS Oregon, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, regenerative agriculture not only offers climate protection benefits and investment opportunities it can also help farmers cope with the chaos climate disruption is bringing to their growing seasons. Rachel McDevitt is a reporter with StateImpact Pennsylvania and has our story.

MCDEVITT: It was raining when I first visited Allegro Winery in southern York County last March, which seemed appropriate. In 2018, Pennsylvania's wettest year on record, grapes here burst on the vines, making them more vulnerable to disease. Owner Carl Helrich says a subsequent cold snap wiped out 3,000 vines.

HELRICH: Okay, now we have a bunch of dead vines, we have to pull them out, we replant them with something else that hopefully won't die.

MCDEVITT: Climate scientists say you can't attribute any one weather event to climate change. But global warming is making extreme weather events more likely. In Pennsylvania, itself a large emitter of greenhouse gases, we're already starting to see it in the form of heavier rain. Helrich says it can cost between $10,000 and $30,000 an acre to plant a new vineyard. He can't afford to start over every couple of years.

HELRICH: So, trying to figure out what we should be planting today, based on the fact we're trying to make really great wine 10 to 20 years from now, it's become really difficult.

Regenerative agriculture practices also include no-till planting, which leaves the previous crop residue in place. (Photo: United Soybean Board, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MCDEVITT: Helrich and fruit growers in Pennsylvania are among the first to feel the effects of a changing climate. They'll have to adapt by finding the right varieties that can weather future storms. But farmers can do other things too, including some that can draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, acting as climate change mitigation. Plants do this naturally: they take in CO2 as food and then transfer the carbon into the soil through their roots, helping create a healthy ecosystem for beneficial microbes in the earth.

RUI: Looks pretty healthy this year.

MCDEVITT: So are you looking at soil health?...

The Rodale Institute in Berks County is calling for farmers to be a larger part of the climate solution by transitioning to what's now called regenerative agriculture. It includes growing cover crops, reducing tillage, diversifying crop rotations, and better managing livestock grazing.

RUI: These things, right? These are the residues from the cover crop from the last winter.

MCDEVITT: During a media day at the research farm last summer, soil scientist Yichao Rui showed off side by side trial plots of corn. In one, a cover crop was planted after the last harvest and allowed to grow over the winter before being flattened. When new seeds were planted, the old cover crop acted as a fertilizer and a weed suppressant. And it held on to organic matter, which is mainly carbon,

RUI: Carbon, it belongs to the soil rather than the atmosphere. So we just want to put it back in there. That's health.

Yichao Rui shows the difference between farming system trials during a media event at Rodale Institute in Berks County in August 2020. (Photo: Rachel McDevitt / StateImpact Pennsylvania)

MCDEVITT: Some tech startups are trying to create markets to pay farmers to trap carbon. President Biden's transition team proposed setting up a carbon bank for the same reason. Rodale says its research shows that if every farmer in the world followed a strict definition of regenerative farming, they could sequester all manmade carbon dioxide emissions. Other estimates are much lower. And some years-long studies have cast doubt that carbon can stay locked in the soil for very long.

EGAN: I think it's possible to really oversell it.

MCDEVITT: Franklin Egan with Pasa Sustainable Agriculture runs a more broadly-focused soil health study, which looks at many of the same practices that fall under the regenerative label.

Soil health is absolutely, you know, the linchpin of any climate adaptation strategy for agriculture.

But he says climate is not the selling point for the more than 100 farms in Pennsylvania and neighboring states that participate in the study.

EGAN: I haven't met any farmers through our study whose primary motivation around soil health is mitigating climate.

MCDEVITT: Egan says if carbon payments do come about, it could help farmers with their bottom lines. The farmers I talked to aren't counting on those checks anytime soon. But what advocates call regenerative agriculture is just a good business move.

MCLAUGHLIN: 'Cause my soil is my number one asset.

MCDEVITT: Take it from Perry County grain farmer Dave McLaughlin. Healthy soil that always has something green growing and is full of living roots and microorganisms is resilient soil. It holds on to water longer through a drought. It can soak up more water during heavy rain events. It keeps nutrients in place, preventing runoff that can harm waterways.

MCLAUGHLIN: Well, there we go. And there's your earthworm holes, that's your living roots.

Grain farmer Dave McLaughlin points to the roots that contribute organic matter to his fields in January 2021. (Photo: Rachel McDevitt / StateImpact Pennsylvania)

MCDEVITT: McLaughlin is holding a clump of dirt and roots that he pulled up with his bare hands, proof of the growing organic matter in his fields. He's been thinking more about soil health over the last decade. He started practicing no-till in the late 90s when his father-in-law retired, and McLaughlin figured he could save time by tilling less.

MCLAUGHLIN: That's not really a lofty reason to all this; I just had to get the work done.

MCDEVITT: But now he's excited to be building up the soil, rather than depleting it. At the Pennsylvania Farm Show a few years ago, McLaughlin gave trays of his soil to use in a rainfall simulator that would show water infiltration and runoff. He expected to switch out the trays over the course of the week, but he didn't need to.

MCLAUGHLIN: And at the end of the week, they were talking 25 to 30 inches of rain, and some of my samples had virtually zero runoff.

MCDEVITT: McLaughlin says he hasn't noticed any effects of climate change on his farm so far. But he knows the methods he uses on his land benefit people downstream and the surrounding environment.

MCLAUGHLIN: I'm doing a better job now than I was 30 years ago. The soils are better prepared than they were 30 years ago. So I'll, I'll just roll with the punches Mother Nature throws at me.

MCDEVITT: Some may be looking to people like McLaughlin and their regenerative practices as a big climate solution, but he just wants to keep his business going, so he can hand it down to the next generation.

BASCOMB: Rachell McDevitt’s story comes to us courtesy of StateImpact Pennsylvania.

Related links:

- Read this story on the StateImpact Pennsylvania website

- StateImpact Pennsylvania Climate Change Explainer

[MUSIC: Rikard From, “It’s an Upright Thing”, Rikard From]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Paige Greenfield, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth