July 5, 2013

Air Date: July 5, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

World Population Day

View the page for this story

The United Nations recently issued a report that anticipates world population will reach 9.6 billion people by 2050, an increase from previous projections. Host Steve Curwood talks with Robert Engelman from the Worldwatch Institute about the factors causing this dramatic population increase. (07:35)

Alternative Tar Sands Pipelines

View the page for this story

While all eyes are focused on the Keystone XL pipeline, oil company Enbridge is quietly planning to expand a web of other pipelines to bring Alberta Tar Sands oil to ports. Lisa Song from InsideClimateNews details the pipeline projects to host Steve Curwood. (06:35)

Bayou Community Struggles with Sinkhole

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

From hurricanes to oil spills, the people in Southern Louisiana are used to environmental threats. But as Emmett FitzGerald reports, a huge sinkhole in the tiny swamp community of Bayou Corne is giving residents unique and unpleasant challenges. (10:40)

Sea Turtle Paternity Test

/ Poncie RutschView the page for this story

A recent study from NOAA scientist Peter Dutton used a new method to test paternity in sea turtles. As Living on Earth's Poncie Rutsch reports in this Note on Emerging Science, the new data will help more accurately estimate population size, resilience, and sex ratios. (01:55)

New National Parks

View the page for this story

This summer, vacationing Americans have five new National Monuments to choose from. Host Steve Curwood talks to Joan Anzelmo from the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees about these special places and how the Park Service is coping with cuts due to the sequester. (06:05)

Rethinking Fast Fashion

/ Bianca BrooksView the page for this story

Youth Radio's Bianca Brooks reconsiders her love of inexpensive fashionable clothes after a visit to a garment factory in Bangladesh. (02:55)

Ritual and Deforestation in India

View the page for this story

As much as 750 square miles of forest are cut down annually for cremation ceremonies in India. George Black, executive editor of On Earth Magazine, tells host Steve Curwood that environmentalists and engineers are working on a more efficient but culturally appropriate way to cremate the 8 million Indian Hindus that die each year. (07:55)

Dancing Gnats

/ Jeff RiceView the page for this story

Gnats are annoying little bugs. But if you know the trick, gnats will actually move at your command. Jeff Rice reports from Idaho. (02:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Robert Engelman, Lisa Song, Joan Anzelmo, George Black

Reporters: Emmett Fitzgerald, Poncie Rutsch, Bianca Brooks, Jeff Rice

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The UN says population will reach 11 billion by the end of the century - and the biggest increases will be in parts of Africa.

ENGELMAN: Can Africa support 4.2 billion people? Can Nigeria support 900 million people at the end of the century, nearly a billion people? You just have to wonder whether these kinds of numbers are really possible on a planet that's already challenged to feed everybody and provide energy and water to everybody.

CURWOOD: Counting the costs of so many people. Also, what's happening under the earth in Bayou Corne, Louisiana.

GREGOIRE: Come home to check on the house, make sure that everything was ok and I noticed there were bubbles in the yard. You could feel the pressure of the bubbles coming out of the ground. It’s nerve-racking.

CURWOOD: The perils of living with a massive sinkhole. We'll have those stories and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic smoothies, yogurt, and more.

World Population Day

The world population is expected to reach double digits by the end of the century. (photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, This is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. There are more than seven billion people alive on Earth today, and a new United Nations report projects population will be pushing 10 billion by 2050. At the same time, climate change is projected to cause significant sea level rise and flooding, as well as more wild fires and destructive storms. It all raises the question of whether our planet can support so many people, especially as resources become scarcer - an important question as we approach July 11, World Population Day. Population expert Robert Engelman is President of the Worldwatch Institute.

ENGELMAN: This new UN report that came out actually says something very significant about population, which is that it is growing faster, particularly in the poorest countries in the world, than demographers had previously thought.

CURWOOD: But let’s look at the regions of the world where you’re expecting to see the most increase in the population. Where should we go?

ENGELMAN: Well, an interesting country to look at is Nigeria. Not too many years ago, the UN demographers thought Nigeria would have about 290 million people in the middle of the century. They’re now projecting 440 million people for the middle of this century. That’s a huge uptick. Chad, Somalia, Uganda, a number of the poorest countries in the world, particularly in sub-saharan Africa, women are having more children than demographers thought they would be at this point in time.

The US has a higher rate of population increase than most other western industrialized countries. (photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: So as I understand it, the US sends a lot of foreign aid for contraception in the developing world. In fact, I think we’re the largest single donor nation. And yet at times, we’ve had this policy that no funds can go to an institution that supports abortion, or in certain cases, even contraception. How has that strategy changed during the Obama administration?

ENGELMAN: Well, the Obama administration has been more open and tolerant to different approaches to family planning and reproductive health than its predecessor. We’ve gone back and forth between Republican and Democrat presidential administrations restricting aid based on whether providers of family planning also give any advice - just even advice - on abortion. If they even mention abortion, Republican presidents restrict their capacity to provide family planning services with US aid. Obama doesn’t have that restriction. But overall, there just hasn’t been much money put in it. It’s been fairly stagnant, even as the population of women who need family planning is constantly growing, and growing pretty rapidly.

CURWOOD: I would think, of course, empowering women would have to be at the front and center of every strategy to get the population under control. Am I missing anything?

ENGELMAN: I think if you need to look to one single strategy that would have the biggest impact on population growth worldwide and indeed in the United States, you would be looking to women and their capacity to make decisions in their own lives - a critical one of which is their capacity to decide for themselves whether, when, which whom, and how often to have a child.

CURWOOD: So Bob, the projected rise of population comes at this time when climate scientists are telling us we’re going to see rises in sea level, more destructive storms, greater floods, wildfires. A lot of people live in the coastal areas that are especially vulnerable. Given the dwindling resources that we see ahead, how many people can this Earth support, do you think? What is the carrying capacity of Planet Earth?

Large families are the norm in many countries in Sub Saharan Africa. (photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

ENGELMAN: No one really knows, Steve. But it is interesting that the UN demographers expect continued increases in life expectancy to the point where the average person will be living 82 years. They expect that to just keep going up because it has gone up for quite a while - which kind of reminds you of financial people who say past results are no guarantee of future performance. They don’t seem to be talking to the climate scientists who are expressing a lot of concern about agricultural productivity in a changing climate, sea level rise, and the UN certainly in the projections, they essentially do assume that the Earth can support any number of people.

CURWOOD: So, what’s the problem here? Is it population? Or is it consumption? I mean, if the world consumed at the same level as a person from Bangladesh or Mali, would we really have a problem?

ENGELMAN: Yes, we actually would. It’s because we are 7.2 billion people that consumption is the problem that it is. But clearly unequal consumption is a huge problem for climate change. Some of us, probably you and me and our fellow Americans, are contributing a lot more to climate change than a person, say, in Mali. But one of the problems is poor countries in terms of their own local environments. Is there enough water in a country like Chad to support another doubling, tripling or quadrupling of its population? That’s not an issue of climate change so much, though climate change might affect it. It’s a question of local resources, arable land, forest, fisheries, renewable fresh water. And that’s the reason that very poor countries, the ones are now growing the very fastest, need to be very concerned about their population growth. And in fact, many of them are.

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about the population rise forecast in the United States. I believe we’re the only industrialized nation that’s going to see our population grow from, what, 300 million at the turn of the century in the year 2000 to more than 400 million by the middle of this century?

ENGELMAN: That’s right, and as high, in these new UN projections, as over 460 million people, nearly half a billion people, by the end of this century. This is partly as a result of the fact we have a lot of young people, and our fertility is somewhat higher than it is, say, in Europe, and other developed countries. And it’s also a result of a topic that’s been much in the news lately - immigration. A lot of people come to the United States, and they contribute to our population growth as well.

The parking lot of the command center (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: Focusing on the United States more, access to birth control and abortion services are pretty hotly contested here still. I was just thinking, not too long ago, Texas state Senator Wendy Davis filibustered for 11 hours to block this restrictive anti-abortion law moving through the legislature in Texas. And of course, earlier this year, the Obamacare provision providing free contraception to women came under attack from certain political parts of the spectrum who likened it to promiscuity. Wow, how advanced are we really, here in the United States?

ENGELMAN: Well, this is an amazing thing for a very developed country with a sophisticated system of health care. We are genuinely conflicted about sex, about contraception, about reproduction, and abortion is the most obvious expression of that. There’s a significant division nationally on abortion clearly, but the fact that it affects whether we want to make contraception as widely available as possible to anyone who wants to use it, is really fairly surprising for a modern developed country in the early 21st century. And the fact that it’s still so controversial in this country is one of the reasons that, amazingly, nearly half of pregnancies that occur in the United States are not intended.

Wilma Subra and Jennifer Gregoire outside of Jennifer’s home on Sauce Picante. The Gregoires are living down the road in Pierre Part, but they come back every couple of days to check on the house.

CURWOOD: So July 11 is World Population Day. What suggestions do you have for people listening to this broadcast about what might be done to commemorate it?

ENGELMAN: The best thing you can do on World Population Day would probably be to write a letter to your representative, your national representative, your state representative, maybe to President Obama, just to say this is an issue that I actually think is really important, that I really care about; I don’t hear you talking about it very much, but I wish you would. I think the public is really interested in this issue, but politicians don’t seem to be hearing that message, and it would be good if they did.

CURWOOD: Robert Engelman is President of Worldwatch Institute. Thank you so much, Bob.

ENGELMAN: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Worldwatch Institute

- United Nations Population Fund

Alternative Tar Sands Pipelines

Lisa Song (photo: insideclimatenews.com)

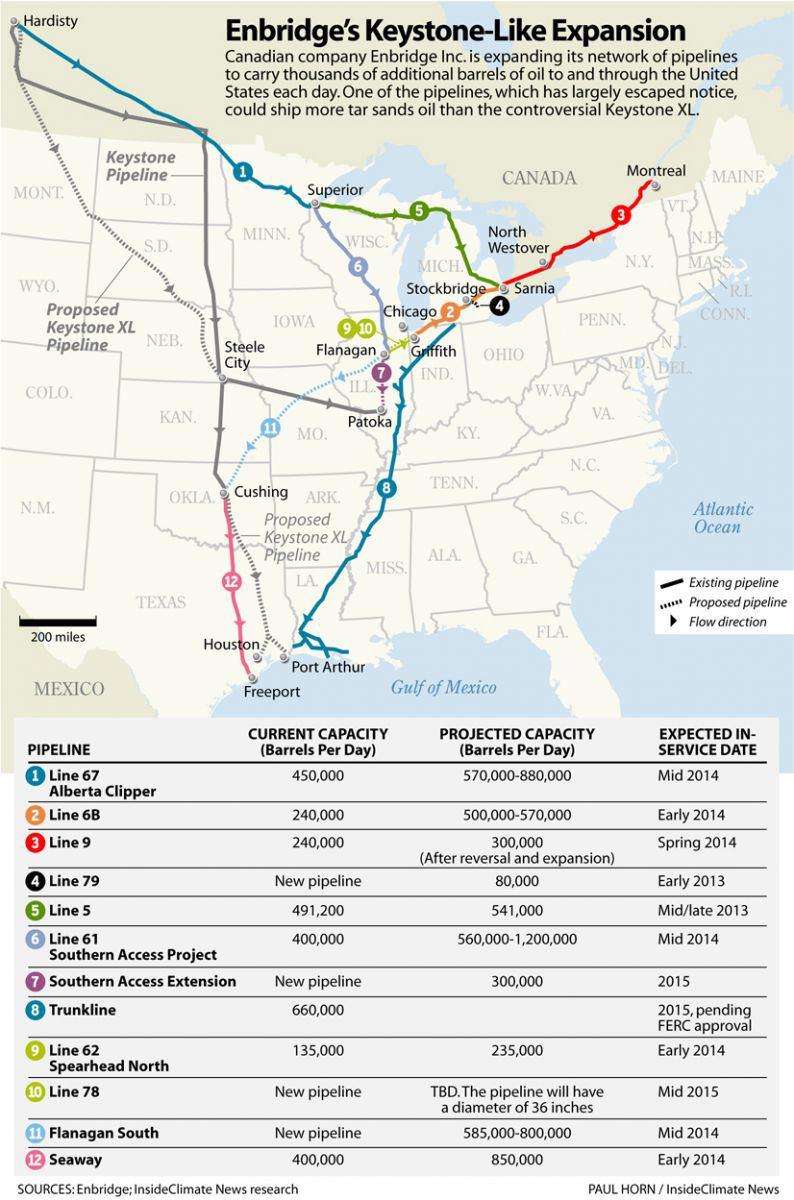

CURWOOD: In his recent address on climate change, President Obama pledged not to approve the Keystone XL pipeline if it would add significantly to global warming. Many Keystone opponents heard that as a death-knell for the project, but the overall climate impact of the pipeline will depend on whether the diluted bitumen, dilbit, from the Canadian Tar Sands would be able to get to the market anyway. And there may be another way. According to the online publication InsideClimateNews, the Enbridge Company has been quietly exploring the expansion of its existing network of pipelines in the US and Canada to get more dilbit to market. InsideClimate’s Lisa Song checked into this, and I went to her office to see the map of the proposed pipeline expansions.

SONG: These pipelines would primarily transport oil from Canada, and means a lot of the same kind of dilbit oil that would be in the Keystone XL. These pipelines would also transport American oil because they’re expansions on Enbridge’s existing network of pipelines in the US. Enbridge right now has an oil pipeline that goes from Canada to Wisconsin, and that carries a little less than 500,000 barrels a day of this dilbit oil. And the company is looking to expand that pipeline and almost double it in size up to 880,000 barrels a day. And if they manage to do that, the pipeline will be larger than the Keystone XL.

CURWOOD: Let’s go to the computer screen now and if you want to follow along at home, we’re at InsideClimateNews.org. And we see a map of Alberta, there’s this web of pipelines. Describe how it gets to Port Arthur and Freeport on the Texas coast.

SONG: Well, it’s hard to say exactly, because it’s a web of pipelines. Some of them go to Montreal; there’s a bunch in the midwest, and then some of those pipelines go down to Texas and the Louisiana gulf coast. The way the oil is moving generally is from north to south, from Canada to the gulf coast. But once you have the oil in a specific pipeline, it’s hard to say exactly where it will go next. But a lot of these pipelines are existing pipelines that Enbridge either wants to increase in size, or transform from one type of pipeline to another. So, for example, there is a pipeline called the trunk line, which goes from the midwest down to the gulf coast. Right now, that pipeline carries natural gas. But Enbridge has a plan to change it to carry crude oil down to the coast.

Map of Enbridge’s proposed pipelines (image: Paul Horn/InsideClimate News)

CURWOOD: Let’s see, looking on the map here, I notice this pipeline that goes over to Montreal. This must be the one that folks are talking about bringing oil out through Maine to the ocean?

SONG: Yes. There’s an existing pipeline that goes to Montreal and it stops there. And right now, Enbridge is reversing that line so they can start pumping oil from the west to the east, to Montreal. And there are environmentalists who are afraid Enbridge will want to expand that line and build it further east from Montreal to Maine, and eventually to the coast. But there aren’t any concrete plans to do that yet.

CURWOOD: Now, if I do the math here - if Enbridge builds this one and there’s a Keystone XL, then all kinds of tar sands oil could come through the US.

SONG: You know, right now in Canada, they’re producing a lot of tar sands oil, and there’s not enough pipelines to bring that oil out of Canada and into the US. So whether both pipelines get built, or just one of them, the industry will certainly want as many as they can get.

CURWOOD: So, what’s the regulatory situation here? Who has to approve this Enbridge plan?

SONG: It’s also the State Department. They have to basically give Enbridge a permit before the company can complete the expansion. The State Department needs to write an Environmental Impact Statement before they can make a decision. And they’re just getting started in that process. So I think they’re taking public comments right now.

CURWOOD: How much pushback has there been from campaigners who’ve been opposing the Keystone XL on the grounds that it would promote global warming?

SONG: There hasn’t been very much attention on the Enbridge pipeline, just because the Keystone has taken up most of the space, and most of the attention. But I think it’s something that people who are opposed to Keystone are aware of, and I’m sure it will get more attention over time. It’s already gotten more attention recently because they put forth a formal proposal to the State Department.

CURWOOD: Lisa Song, give us the quick science lesson about why there’s such concern over this diluted bitumen and the process of getting it out of Canada?

SONG: Well, the problem is, bitumen is thicker than conventional crude oil, the type of light and medium crude oil that we’ve traditionally shipped in the US, and that our pipelines were built to ship. So when this oil spills out into the environment, what happened, for example, three years ago in Michigan, there was a million gallon dilbit spill in a river. And once the dilbit spilled, the light chemicals eventually evaporated, and all you had left was the heavy bitumen, and it sank to the bottom of the river where it’s really hard to clean up. So that’s the worry that if we start shipping more of this dilbit, then what happens when it spills? We still don’t know how to clean it up.

CURWOOD: Now recently, the National Academy of Sciences had a report looking at pipelines carrying both crude and diluted bitumen, and said they’re about the same. But what kind of assessment do they give in case of a spill?

SONG: So the study only looked at whether diluted bitumen is more corrosive to pipelines than regular crude oil. The NAS scientists did not look at the consequences of a spill at all. And that’s because the study they did was ordered by the Department of Transportation, and it came out of a pipeline safety bill that was passed in 2012. So the DOT told the academy, we want you to say whether pipelines are more likely to leak when they have diluted bitumen in them rather than conventional oil, but they did not ask the committee to look at what would happen if diluted bitumen spilled out of the pipeline. And so that means part of the question about the risks of dilbit and how it compares to regular crude oil hasn’t been answered.

CURWOOD: Lisa Song is a reporter with InsideClimateNews. Thanks so much, Lisa.

SONG: Thank you.

Related links:

- Read Lisa Song’s article here

- Lisa Song’s staff page at InsideClimate News

[MUSIC: Bonobo “Black Sands” from Black Sands (Ninja Tune 2010)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...when your yard starts to bubble, you know you’ve got trouble. That's next on Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Hampton Hawes: “The Awful Truth” from Four (Fantasy Records 1988 Reissue)]

Bayou Community Struggles with Sinkhole

The sinkhole from the air. It is now approximately 20 acres in size. (photo: Louisiana Environmental Action Network).

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The people in the bayou country of southern Louisiana are used to environmental anxiety - what with frequent hurricanes, oil spills, and chemical explosions at plants along what’s known as the petrochemical corridor. But for the past year, residents of the tiny town of Bayou Corne have been struggling to cope with an unexpected new problem that opened up right in their own backyard. In August 2012, a sinkhole appeared just outside of Bayou Corne and it's grown to nearly 20 acres in size. It’s brought tremors, dangerous gasses, and a host of uncertainties to the people living there. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald has our story.

FITZGERALD: Residents of Bayou Corne, a small community on the edge of a cypress swamp in southern Louisiana, call the place a “bayou paradise.” Dredged canals snake between the streets. Each house has a driveway out front and a dock out back with boat access to the bayou.

Nearly every home in Bayou Corne has access to canals that lead to the swamp (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

SUBRA: I mean, if you were from New York City and you came down here you thought you were in heaven here, right?

FITZGERALD: Wilma Subra is an environmental scientist.

Wilma Subra, environmental scientist with the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

SUBRA: They even have a little Mardi Gras parade.

FITZGERALD:Right down this street?

SUBRA: Uh huh. Isn’t it beautiful?

FITZGERALD: Wilma’s been monitoring the sinkhole since it appeared. As we drive into Bayou Corne, the tranquil town looks more like a construction zone. Dump trucks and backhoes trundle past, kicking up clouds of dust. Wilma says they’re building a sand berm around the site.

[DRIVING ON THE ROAD]

FITZGERALD: Through the trees we catch a glimpse of the sinkhole.

SUBRA: Look down there.

FITZGERALD: Oh yeah, oh my God.

SUBRA: You saw it?

FITZGERALD: Yeah, it looks just like a lake.

SUBRA: Yeah, with crude oil floating on top on it.

FITZGERALD: We turn down a quiet street lined with small, brick homes, and Wilma spots a familiar man in a sweaty shirt pushing a mower across his yard.

SUBRA: Hi, Dennis. He can’t hear me. Hi.

[LAWN MOWER TURNS OFF]

LANDRY: How ya’ll doing?

FITZGERALD: Good. How are you doing?

LANDRY: Too hot. Well, we got an interesting little story going on here.

FITZGERALD: Dennis Landry was born on the bayou. He owns a lodge called Sportsman’s Landing with three “Cajun Cabins” for fishermen and honeymooners. Since the sinkhole, Sportsman’s Landing has served as the command center for various government agencies. As dump trucks rumble by, Dennis says he saw the early warning signs of the disaster to come in June 2012.

The view from Sportsman’s Landing, Dennis Landry’s business (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

LANDRY: My wife and I were out for a leisurely pontoon boat ride down Bayou Corne.

FITZGERALD: The Landrys noticed strange bubbles rising up in the swamp.

LANDRY: When I first saw the bubbling I looked at it and said, this doesn’t look right.

FITZGERALD: Dennis thought it must be a leak in a nearby natural gas pipeline. But when he called the gas company, they weren’t so sure.

LANDRY: They called me back and said, ‘thanks for calling it in, but we really don’t think it’s our pipeline’. And I couldn’t believe it. I said ‘golly, it’s only twenty feet from your line.’

FITZGERALD: The gas company was right. Scuba divers checked it out, and the bubbles were coming directly from the ground. For the next few weeks, officials tried to sort out what was going on.

LANDRY: Then of course the world changed, on August 3rd. August 3rd, the sinkhole occurred at the Texas Brine facility, and everyone pretty much knew immediately, an old abandoned cavern that they had shut in a couple of years prior, apparently had failed.

FITZGERALD: Now, it takes a little geology lesson to understand all this. Under Louisiana’s swampy earth lie massive fingers of salt. Companies drill into these “salt domes” for a variety of reasons. Some mine salt to melt ice on roads up north during the winter. Others store natural gas in the salt caverns. And some companies drill into the domes to make brine.

Sonny Cranch is the director of media relations for Texas Brine, a company that has been drilling into the salt dome beneath Bayou Corne for over 30 years.

CRANCH: The process is to drill a well down to about 6,000 feet and start injecting water.

FITZGERALD: The water dissolves the salt creating a hyper-saturated solution. Next, the company pumps the brine to petrochemical plants along the Mississippi river, where they use the chloride to make plastics.

CRANCH: We’ve heard of polyvinal chloride, PVC pipe, well guess what, this is where that comes from.

FITZGERALD: This particular cavern was drilled in 1982. After nearly 30 years of extracting brine, the company began to notice structural problems in 2010. In June 2011, with approval from the Office of Conservation, they plugged the well and closed the cavern.

CRANCH: And a year and two months later we have a sinkhole appear. It’s right up there.

FITZGERALD: What exactly happened is still a little unclear, but at some point after Texas Brine abandoned their operation, the side of the salt cavern collapsed, causing the sinkhole to open up at the surface. As debris continues to slough off the sides, the sinkhole keeps growing. Right now,

BOUDREAUX: it’s about a thousand foot in diameter.

FITZGERALD: And how deep?

BOUDREAUX: Last sonar put it at about 174 feet at its deepest point.

FITZGERALD: John Boudreaux is the Director of Emergency Preparedness for Assumption Parish, where Bayou Corne is located. Parish officials are currently running tests to determine how big the sinkhole will get. Many residents have reported feeling tremors, but at this point, Boudreaux says the biggest threat has to do with that mysterious bubbling in the bayou. When the sinkhole opened up, it released natural gas from deep underground into the aquifer beneath Bayou Corne.

BOUDREAUX: The risk to the community, number one, the shallow gas, of it coming to surface especially underneath a home and possibly getting up to an explosive level.

FITZGERALD: So, to avoid explosions and reduce the gas in the aquifer, Texas Brine is flaring it off around the clock. Flames leap from pipes sunk into the ground. Although Boudreaux put the town on an evacuation order back in August, about a third of the residents have stayed. Texas Brine installed air-monitoring equipment in many of their homes, including Dennis Landry’s.

The sinkhole from the air. It is now approximately 20 acres in size. (photo: Louisiana Environmental Action Network).

LANDRY: So we’re living with gas monitors in our homes to alert us. In the unlikely event that gas would get under our slabs and somehow work its way into the house.

FITZGERALD: Dennis is determined to stay in Bayou Corne, but not everyone is as willing to risk it. As Wilma and I turn onto a street called Sauce Picante, we spot two kids playing in the backyard of a small white house. I knock on the door to see who’s home.

[KNOCKING, COUNTRY MUSIC PLAYING]

FITZGERALD: Jennifer Gregoire has been living in Bayou Corne for the past six years.

[HOUSE DOOR OPENS]

GREGOIRE: Hi.

[FITZGERALD: Hello.

Most families in Bayou Corne own their own boat (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: She and her husband were raising their family here, but she says the sinkhole changed all of that.

GREGOIRE: Come home to check on the house and see that everything was ok and I noticed there were bubbles in the yard. So we call John Boudreaux and he come out, and you could feel the pressure of the bubbles coming out of the ground. It’s nerve-racking.

FITZGERALD: Jennifer and her husband decided that they couldn’t put their children in danger, so they moved out. For the first few months they bounced between hotels, coming home every few days to check on the house. Jennifer says it was tough on the kids.

GREGOIRE: People yelling in the hotels. You don’t know who they are, who’s living next to you. It’s not fun. It’s not a good situation.

FITZGERALD: Eventually the Gregoires bought a camper in the nearby town of Pierre Part. Since the sinkhole, Texas Brine has been paying every household $875 a week for housing and other costs. Jennifer says it’s not enough.

GREGOIRE: It took everything we had to get a camper. No help from Texas Brine, what does $875 do a week? How far can you stretch that between a mortgage, husband working out of state. We had to wait until after December to buy a camper.

FITZGERALD: Sonny Cranch is quick to point out that Texas Brine didn’t want any of this to happen.

CRANCH: Texas Brine didn’t sit down and say, let’s just see if we can cause a breach and ruin everybody’s lives, including ours. It happened, and we’ve been trying to deal with the aftermath ever since.

FITZGERALD: But when homeowners began calling on Texas Brine to buy them out, the company was slow to respond. On May 20, 2013, Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal came to town with strong words.

JINDAL: More than 350 lives have been impacted by this sinkhole. For months we’ve been pressuring Texas Brine to step up to the plate and do the right thing. They are responsible for this sinkhole. They need to clean up the mess they have made; they need to do right by our people.

Bayou Corne residents send a message to Texas Brine with these piece of public art (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Jindal’s speech might have had an effect. On May 25th, Texas Brine announced buyout offers based on the value of the property in the spring of 2012, plus some cash for additional expenses. As of the end of June, 44 homeowners had agreed to terms with the company. But the Gregoires aren’t interested in dealing with Texas Brine.

GREGOIRE: To be frank I don’t want to speak with Texas Brine about the buyout.

FITZGERALD: Jennifer says she doesn’t trust the company, and that one of her neighbors got an offer that was far too low.

GREGOIRE: $75,000 dollars less than what their house was appraised for. No thank you.

FITZGERALD: Along with many other residents, the Gregoires are now filing suit against the company. This is the first known example of a sinkhole caused by the collapse of a salt brining cavern, but Wilma Subra says the whole situation is painfully familiar. In 2003, a natural gas storage cavern leaked into the aquifer beneath the town of Grand Bayou, just down the road from Bayou Corne.

SUBRA: It was very explosive so the people couldn’t live there any longer. And they’ve been relocated and the houses destroyed and all you can see is the slabs where the houses were.

FITZGERALD: On June 13th 2013, a petrochemical plant exploded in Geismar, Louisiana, just 30 miles from Bayou Corne. Two people died and over 75 were injured. And reports of elevated cancer rates along Louisiana’s petrochemical corridor have earned the region the nickname, “cancer alley.” This sinkhole may be unique, but environmental crisis is an everyday reality in southern Louisiana. Wilma Subra.

SUBRA: It’s not like a waste site that was a sin of the past. The degradation of the environment and the quality of life is occurring now, every single day.

FITZGERALD: Back at Sportsman’s Landing, Dennis tells me that he’s tired of living with uncertainty.

LANDRY: The progress has been woefully slow, and uh, life is kind of almost in limbo.

FITZGERALD: The sinkhole saga doesn’t seem to be winding down any time soon. On June 21, the hole “burped,” as giant gas bubbles rushed to the surface. That day, residents felt tremors and smelled crude oil. Still, Dennis hopes that someday things can go back to normal. Bayou Corne is his home, and he wants to stay.

LANDRY: The reason we want to leave is, this is not a sales pitch, Bayou Corne is a beautiful little bayou paradise, and you know sometimes even the people who live here, they didn’t appreciate what they had until they were threatened with losing it.

FITZGERALD: For now the threats remain, the uncertainty remains, and so does the sinkhole. And the residents of Bayou Corne, living in limbo, will just have to keep waiting. For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett FitzGerald in Bayou Corne, Louisana.

Related links:

- Check out Wilma Subra’s staff page at the Louisiana Environmental Action Network

- Here’s the web page for Dennis Landry’s business, Sportsman’s Landing

- For updates on the sinkhole, visit the Assumption Parish website

[MUSIC: Beausoleil “Zydeco Gris Gris” from Cajun (network Records 2013)]

Sea Turtle Paternity Test

Leatherback sea turtles are the largest species of sea turtle, and are critically endangered. Previously, scientists have taken a small skin sample from female turtles when they come ashore to lay eggs. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: It's summer! Time to celebrate and visit some of the new national parks and monuments in America. But first this note on emerging science from Poncie Rutsch.

RUTSCH: For years, scientists have looked at sea turtles and wondered, “Who’s your daddy?”

Tracing paternity in turtles is tougher than you might think. First, there’s very little research on male turtles - since they don’t lay eggs, they rarely come ashore, and so scientists seldom get a chance to test their DNA.

Second, sea turtles don’t have sex chromosomes, so it’s hard to distinguish mom DNA from dad DNA. Instead, the egg’s temperature during incubation determines whether it will hatch into a male or female. The warmer eggs tend to be female, and since climate change is warming tropical beaches, scientists thought that females probably outnumbered males in the ocean.

Now, sea turtle scientist Peter Dutton knows that that’s not the case. Dutton and his colleagues at NOAA managed to separate out paternal DNA and found that sea turtle populations had much greater genetic diversity than they’d predicted, indicating that sex ratios are most likely evenly balanced.

A leatherback turtle hatchling races towards the ocean. Scientists can now use low-impact blood samples from these hatchlings to trace turtle paternity. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Dutton discovered this by eliminating the female mitochondrial DNA from the rest of the turtle’s genetic material. The team’s most recent study focused on critically endangered Leatherback sea turtles, and will help to estimate population size and resilience.

The new discoveries also show that leatherbacks tend to return to the beaches where they were born. But the researchers noticed that a few females get off course each year and end up laying their eggs in Baja California, which is too far north - the sand is too cold to incubate the eggs. Still, if the planet continues to warm, those may be the sea turtle hotspots of the future.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science, I’m Poncie Rutsch.

Related link:

NOAA

New National Parks

Rio Grande del Norte National Monument

CURWOOD: It's a kind of familiar ritual of summer: pack up the family and head out for the great American road trip -- maybe to camp and visit some of our national parks and monuments. And if you have that plan for this summer, there are a couple of new additions to the national park system you might consider seeing. To learn what's new and hear how the national parks are coping with tighter budgets from the sequester, we called up Joan Anzelmo, of the National Park Service Retirees.

ANZELMO: There are three that came to the National Park Service. That’s the Charles Young Buffalo Soldier’s National Monument in Ohio, First State National Monument in Delaware, and Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument in Maryland. Two other national monuments were also added to the BLM [Bureau of Land Management] system - San Juan Islands National Monument in Washington and the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument in the Taos Plateau.

Joan Anzelmo (Photo: National Park Service)

CURWOOD: So tell me what’s special about some of these places?

ANZELMO: When you learn a little bit about Colonial Charles Young, who led the Buffalo soldiers late in the 1800s, he has a phenomenal story that I certainly wasn’t aware of until I began to study what this monument is all about. He was the highest ranking African American officer of the time. He was only the third to graduate from West Point in that era in our history. And he led two regiments of Buffalo soldiers after the Civil War. And he was the first superintendent - acting superintendent - of what is today Sequoia Kings Canyon National Park.

So his story is very captivating, just like Harriet Tubman, who we all know from our history that she helped to free many slaves in the east using the Underground Railroad. So those lands, and some of the structures that aided in protecting slaves, safe houses and so on, have now been officially named a national monument. So I think all of us were excited to see that designation.

CURWOOD: Remind folks just exactly what was a Buffalo soldier?

Charles Young (Photo: National Park Service)

ANZELMO: The Buffalo soldier were regiments of African-American soldiers who didn’t get the recognition that they certainly deserved at the time, and they suffered under a great deal of prejudice, as you can only imagine for that era in our country’s history. And it was Native Americans who reportedly termed African-American soldiers of the day Buffalo soldiers because of their dark skin and because of the curly hair. And the African-American soldiers, the Buffalo soldiers took that as a sign of honor, and it stuck.

CURWOOD: Now the same month that President Obama designated these new monuments, Congress wasn’t able to come together on reducing the deficit and put us into this deep sequester cut situation. How’s the rest of the National Park System doing in the face of this sequester?

ANZELMO: All the federal agencies are struggling under reduced budgets. How could you not? Those sequester cuts came midway through the fiscal year, and at least in the National Park Service, they were made across the board. So my colleagues, who still work in the National Park Service where I once worked, have told me and my colleagues in the coalition that they’re having a really hard time. They have reduced seasonal staff levels, obviously the cost of doing business is much more expensive in 2013 than it was a few years ago, and yet the budgets have remained fixed. So they’re trying to do ever more with not only less, but truly diminishing resources. And at some point, the agency and the parks will hit a breaking point.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about some of the places that are really suffering as a function of the sequester if you can.

ANZELMO: You know, in June, for example, in Grand Teton National Park, on two consecutive weeks, there were dozens of emergency responses. Some of those were major mountain search and rescues. Some people were rescued in those missions. Sadly one person fell to his death in one of those. And at the same time there were large scale search and rescue missions taking place in the Teton Mountains, there also were other medical responses, emergency calls...the rangers and the other support staff would basically clear one incident only to be called right back out. So I know that day in and day out, whether it’s Grand Teton or many of the other parks in the country, the staff are pressed to do their job of protecting the resources, serving the visitors, and in the case of so many of these parks where people seek adventure, they’re spending many hours helping visitors who may get into trouble. Over the course of this summer, I think those cumulative effects of reduced staffing levels, reduced hours of service for the public, will actually take a toll.

CURWOOD: Now, before you go Joan, since you are in touch with pretty much all of the national parks through your service on the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees, we want you to let us in on a couple of secrets, do you mind?

Grand Teton National Park (Photo: National Park Service)

ANZELMO: [LAUGHS] OK.

CURWOOD: Suggest a place that maybe everyone doesn’t know or is great to take a small kid.

ANZELMO: You know, since there are national parks and national monuments now in every state and many territories of our country, I really think that is what a person has time to get to. So there are experiences, literally, at every single park, whether you are on the east coast and want to learn about the history of the revolutionary period, go to Philadelphia, go to Independence National Historical Park, there’s fabulous things for young people and adults. That would be true on the opposite coast, you know, go to Muir Woods, go to Cascades, go to any part of the country that you have easy access to. It’s sort of like how do you pick your favorite child. There are over 400 wonderful units of today’s national park system, and every unit has something for somebody.

CURWOOD: Joan Anzelmo is with the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees. Thanks so much for your time.

ANZELMO: Thank you.

CURWOOD: I’ll fill up my water bottle and go hiking.

ANZELMO: Sounds like a plan!

Related links:

- Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers NM, Ohio

- Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad NM, Maryland

- First State National Monument, Delaware

- Rio Grande del Norte NM, New Mexico

- San Juan Island NM, Oregon and Washington

- The Coalition of National Park Service Retirees

[MUSIC: Donald Fagan “The Weather Inside Your Head” from Sunken Condos (Reprise Records 2013)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...trying to recast Hindu rituals to protect the environment. Stayed tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Toad’s Place “94” from West Side Stories (Verve Records 1994)]

Rethinking Fast Fashion

A clothing vendor in Dhaka, Bangladesh. (Photo: Adnan Islam)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Most topics we cover on Living on Earth relate to the environment and the natural world. And that includes human ecology and the human cost and destruction we cause with some of our choices. The collapse of a garment factory in Bangladesh this spring forces us to consider those kinds of issues. And it also made Bianca Brooks of Youth Radio rethink her love of fast fashion.

BROOKS: I love fashion. I’ve always loved it. I celebrate fashion week like it’s a holiday. But earlier this year, I realized the true cost of my trendy clothes when I met a group of women I’d been stealing from my whole life.

As part of an exchange program, I traveled eight thousand miles, from Oakland, Calif., to Dhaka, Bangladesh. On a tour of Dhaka, I visited a factory that was making clothes for some of my favorite brands. I saw hundreds of workers crowded around sewing machines and work tables. The sound of whooshing looms and the chemical smell of dye filled the air. But it was watching a young girl sewing a pair of jeans that made me feel really sick. My host sister later told me that many of these workers, mostly women and children, were living on less than $2 a day.

Suddenly, I looked at all the cute outfits I’d picked out for this trip in a completely different light. Before I'd seen the factory, I was so flattered when my new Bangladeshi friends had complimented my elegant name-brand button down. They were proud that the tag on the shirt said Bangladesh. But after, all I wanted to do was wrap my traditional Bangladeshi shawl around me to cover the shame I felt.

I’d been home from my trip for three months when I saw the horrifying headlines reporting more than a thousand people dead from a factory collapse. I know this was not the same factory I had visited, nor were these the same women or children I’d met, but I still felt close to them, and responsible somehow.

I decided to do something. To raise money and spread awareness, I organized a fashion show that featured clothes handmade by Bangladeshi craftspeople, as well as clothing manufactured in Bangladeshi sweatshops, the kind we're use to buying. People marveled at the clothes. But it wasn’t until they saw the pictures of the workers that they began to feel what I had felt – empathy and guilt.

Since I got back from Bangladesh, I haven’t purchased any sweatshop clothes... yet. I either thrift or suck it up and look for American-made brands. But it’s worth it, because there’s a hidden cost in cheap clothing. It involves someone’s livelihood, education, life and the environment. Though I will admit, it also feels better knowing companies like H&M, Tommy Hilfiger and Calvin Klein have promised to step up building improvements and safety inspections in their factories.

That way, if I’m tempted to buy something from Beyonce’s new summer line, maybe it will feel a little less like stealing.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bianca Brooks.

Related link:

Check out more stories from Youth Radio

CURWOOD: Bianca Brooks’ essay comes to us from Youth Radio. It was produced by Ike Sriskandarajah.

[MUSIC: Tal M Klein “Exodus from Sonapur” from Six Degrees Of The Middle East (Six Degrees Records 2004)]

Ritual and Deforestation in India

Sandalwood prepared for a cremation. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: The Ganges is a holy river, especially for the one billion Hindus who live in India.

But the combination of pollution and cremation rituals have led to an environment that can feel far from hallowed. George Black is Executive Editor of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s magazine, On Earth, and he recently wrote about the Ganges. George, welcome to Living on Earth.

BLACK: Thank you, Steve. Nice to be with you again.

CURWOOD: First all, describe for me the city you visited, Varanasi, and its cultural role in India. It’s probably, of all the sacred places in India, the most sacred and revered. It actually...you know people talk about Jerusalem or Mecca or whatever being the center of the universe? Hindus actually literally believe that this is where the universe was created by the god Vishnu and where he left, supposedly in myth, the imprint of his sandals while he was doing the creation, that is where the cremations happen, right on the banks of the Ganges. It’s the most sacred spot in the whole country. And the idea is if you are cremated there, you actually break the cycle of reincarnation.

CURWOOD: What do you mean...break the cycle of reincarnation?

BLACK: Well, Hindus believe you’re endlessly reincarnated as one form of life or another depending on the nature of your deeds while you were alive, and you can be anything from an elephant to a cockroach, depending on your [LAUGHS] stored up good deeds. But the idea is in Varanasi, which they call the city of light, which they believe is suspended above the earth, and above time and space, if you die there and your ashes are scattered on the holy river, the Ganges, then you will actually, once and for all, go to heaven, and join your ancestors, and be released from the pains of reincarnation and rebirth. And people literally come to Varanasi to die. The ultimate virtue is you actually physically die there, and are cremated there, and are put in the Ganges there.

CURWOOD: The irony, of course here, George, is that the Ganges River is one of the most polluted waterways in the world. How polluted is it, and how did it get that way?

BLACK: Well, in terms of bacteriological contamination, it is literally thousands of times worse in coliform bacteria than World Health Organization standards, but it’s not just that. The Ganges rises in the Himalyas, many hundreds of miles upstream, and it’s affected by a huge number of factors along the way. One is that climate change is changing the flow of the river, variable monsoons; the river levels can drop very low so the pollution is more concentrated; there’s dams; there are a string major cities that dump their raw sewage; their tannery effluent...the big industry in India is tanneries; their chemical works discharge directly; they don’t have effluent treatment plants. So by the time you get to Varanasi and you add that city’s quotient of the effluent, you’re really dealing with something that smells bad, it looks bad, you have dead animals floating in it. I mean, it’s really a problem with all of India’s major rivers.

CURWOOD: And this one is really an open sewer, you’ve described.

BLACK: Yes. Basically I think that’s accurate, quite literally, the sewage runs into the Ganges, at one spot literally 50 yards above, upstream from the reincarnation ground. But if you’re a Hindu, you have a different conception of pollution that is not irreconcilable, which is a notion of purity. The river is a goddess, the goddess Ganga, and by immersion in it, there are thousands upon thousands of pilgrims there all the time who take what they call their holy dip in the river. They regard that as a purifying thing. They may get sick afterwards,;a lot of them do. But there are just two conceptions of purity.

CURWOOD: So let’s do the math here that you have in your story. You say there are some 10 million people a year who die in India, the bulk of whom are cremated with wood fires. So at the end of the day, how much wood are we talking about here?

BLACK: Well, it’s been calculated to about 750 square miles of forest every year. Depending on the economic status of the dead person’s family, depending on the level of piety, you can be talking about anything up to 1,000 pounds of wood, which is a huge pile of wood. All the streets around the cremation grounds of Varanasi are stacked 20, 30 feet high with wood. And what people who are concerned about the environmental costs of this, and are trying to challenge the really fundamental tenets of a great religion, what they come up against, is how do you reduce the amount of wood without going to a western style closed cremation system, which has been largely rejected in India because you can’t observe the funerary rights - which are very elaborate.

Varanasi, India is the holiest site in India to be cremated for Hindus. (Bigstockphoto.com)

The mourners have to walk around the corpse. The fire supposedly has to be lit in the mouth of the corpse. There are some rituals that, shall we say, are disconcerting to a Western visitor, including breaking open the skull during the act of cremation so the soul can be released. And you can’t do any of that if you’re feeding somebody into a gas oven in an electric-powered crematorium. So this is the dilemna, how could you have an open pyre, and at the same time, allow people to conduct these rituals? And there is a group in New Delhi, that I visited and witnessed their cremation system, who have come up with a design that works pretty well. It’s metal, it’s kind of perforated - although it’s too technical to describe - but you can get away with burning 200, 300 pounds of wood instead of burning 600, 800 pounds.

Varanasi on the Ganges River (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: So, I understand there are a lot of cultural and economic interests that keep the demand for cremation wood high. Can you tell me about that?

BLACK: Yes, it’s basically a big business as well as a religious business, and like a lot of things in India, there are middlemen who take cuts and commissions and bribes along the chain. And that goes all the way from the illegal woodcutting in the forests -- where I asked somebody...I saw these people in the forest with axes and I said to somebody, ‘Well doesn’t the forest department send out guards to monitor this?’ And he said, ‘Oh yes, they go out every day.’ And I said, ‘Well, what’s the problem?’ And he said, ‘No, you don’t understand. They go out every day to take bribes so they will look the other way and ignore the illegal logging.’ So you go from that through the auction depots where the wood is sold, the trucking companies, the brokers, and you finally end up at the cremation grounds, where even the priests can have a stake in it.

CURWOOD: And so they’ll push you to buy more wood?

BLACK: Oh yes. And they’ll also say, ‘you know you want to be a good Hindu...remember what your ancestors did...remember how much wood they burned and they were guaranteed their place in heaven and you don’t want to take any chances’. And they could be also taking a cut themselves. I went to one cremation ground in New Delhi where the priest was actually selling the wood. So obviously you’ve got an incentive to sell more.

Portions of the Ganges River are considered to be open sewers. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: So how likely is it that the new technology that you described to allow traditional open air cremation but cutting the amount of wood, how likely is that to catch on?

BLACK: Well, I went to Varanasi to test that proposition because it’s almost the most extreme challenge they’ll face. I think in other places, you can begin to see it taking off in cities like New Delhi, Bangalore, Calcutta, Mumbai, where you have a sizeable, more westernized middle class that’s less attached to ritual. But I think when you come to grips with the majority India, you realize that transforming things like environmental practice, you’re really talking about a matter of centuries, possibly even a millenium. It’s going to be slower in Varanasi than anywhere else.

CURWOOD: George Black is Executive Editor of OnEarth magazine for the Natural Resources Defense Council. Thanks so much, George, for taking the time.

BLACK: Thank you, Steve, for having me.

Related link:

India’s Forests, Fires, and Funerals

[MUSIC: Bombay Dub Orchestra “Monsoon Malabar” from 3 Cities (Six Degrees records 2008)]

Dancing Gnats

Common gnat (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Now, here's a story about one of those tiny creatures of summer that play such a vital part of our planet's biological diversity, even if it seems that their only reason for existence is to annoy us. From Idaho, Jeff Rice explains how to have fun with gnats.

RICE: Near the Boise foothills, the river ambles through the pastures and cottonwood groves. The late afternoon sun gives the marsh grass a soft focus. And a blizzard of gnats rises up near the water’s edge where a man is humming.

[HUMMING]

RICE: But he’s not humming to himself, and there’s no real tune.

ROBERTSON: [SHORT HUM] They just think I’m crazy [LAUGHS].

Jeff Rice (photo: University of Washington)

RICE: Dr. Ian Robertson is an entomologist at Boise State. One day, when we were talking about something completely different, he casually tells me that you can hum to gnats and in a sense, they’ll dance for you.

ROBERTSON: [SHORT HUM] Just a simple hum [SHORT HUM].

RICE: He says it’s just one of those things that’s passed around from entomologist to entomologist. I believed him not just because I wanted to, but because it actually makes sense.

ROBERTSON: Well, the males have special organs at the base of their antennae that can detect the wing frequency – the vibrations of the female’s wing. And so when a female flies into the area the males detect that and then all swarm towards her. And so when humming we’re trying to mimic the frequency of the wing beats of the female in terms of the sound it makes [SHORT HUM].

RICE: And it actually works.

ROBERSTON: [SHORT HUM]

RICE: Hum, the gnats move forward. Stop humming, they stop. Forward, stop.

ROBERTSON: [SHORT HUM]

RICE: Clouds of gnats shift direction like flocks of birds. Then they become liquid; they move and surge almost like a tide lapping against the shore. And the humming pulls them like an undertow.

ROBERSTON: You see how just the whole group of them speeds up when that happens [SHORT HUM]. Then as soon as you stop they just go back into their normal flight pattern [SHORT HUM].

RICE: [HUMS]

ROBERTSON: [HUMS]

RICE: It’s not long before we are controlling whole fields of them. It’s nothing short of beautiful, a swirling Busby Berkeley musical of insects. And it gives me an idea: if this works with a couple of people, think of the possibilities.

[TUNING SOUND]

RICE: Hit it!

[GROUP HUMMING]

RICE: So did we attract any gnats?

SINGER: I had one fly up my nose [LAUGHTER].

CURWOOD: Our lesson on how to make gnats dance was produced by Jeff Rice. Choral humming courtesy of the Boise State Chamber Singers.

Related link:

Listen to more of Jeff Rice’s work on Hearing Voices

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with the sounds of a summer night in the Cascade Mountains of Northern California.

[CRICKETS AND CICADAS CHIRPING]

Crickets and Cicadas form the backdrop to the splashes and croaks of bull-frogs.

[BULLFROGS CROAKING]

[SPLASH]

A great horned owl out hunting hoots occasionally

[OWL HOOTING]

CURWOOD: Bernie Krause and Ruth Happel recorded this chorus for the Wild Sanctuary CD Midsummer Nights.

[MUSIC: Earth Ear: Bernie Krause/Ruth Happel “Midsummer Nights: West” from Wild Sanctuary: Midsummer Nights (Four Winds Records 2002)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Poncie Rutsch, Erin Weeks, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. We had engineering help this week from Dana Chisholm. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org. And check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood.

Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of Red Tomato, supplier of righteous fruits and vegetables from northeast family farms. www.redtomato.org. This is PRI Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth