September 27, 2013

Air Date: September 27, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Humans Change the Climate

View the page for this story

A landmark report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says scientists are 95% certain that humans are responsible for global warming. Harvard scientist James J. McCarthy tells host Steve Curwood that arctic ice continues to melt and sea levels are rising faster than earlier predictions, as almost all of the planetary warming is being absorbed by the oceans. (08:00)

A Challenge for Coal

View the page for this story

The EPA has revised proposed regulations for greenhouse gas emissions from new power plants. UCLA environmental law professor Ann Carlson tells host Steve Curwood that coal plant developers may find it tough to meet the new standard, and novel approaches will be needed to successfully regulate existing coal power stations. (06:10)

Science Note

View the page for this story

Researchers have discovered a natural hydrocarbon in the roots of a grass that could reduce greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture. Andrew Keys reports in this week’s Note on Emerging Science. (01:50)

Toads in Tuscon

/ Sarah BromerView the page for this story

The US southwest is typically a dry and dusty desert, yet in summer torrential rains can spawn the sudden appearance of noisy amphibians. Sarah Bromer reports from Tucson. (08:30)

National Geographic 125 Year Anniversary

View the page for this story

The National Geographic Society’s magazine is celebrating its 125th anniversary with a special edition featuring some of its most iconic photographs. Sarah Leen, the magazine's director of photography, talks with host Steve Curwood about the magazine’s history and some of its most compelling images. (06:20)

The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars

View the page for this story

In a 2009 incident that came to be known as 'climategate', several climate scientists had their e-mails hacked and quoted out of context in an bid to discredit the researchers and their work. Host Steve Curwood talks with Penn State meteorologist scientist Michael Mann, who was a target of the attacks and has now written a book about the experience. (12:30)

The Quarry

View the page for this story

Writer Rod Clark revisits an old limestone quarry full of memories near the village where he grew up, and finds the towering cliffs and hidden caves still a magnet for children today. (02:30)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell “The Pioneers” from Good Dog, Happy Man (Nonesuch Records 2000)] [SOUNDS OF BIRDS AND HUMMINGBIRDS’ WINGS] CURWOOD: And we leave you this week with writer Mark Seth Lender, and recordings he captured of hummingbirds in Madera Canyon, Arizona. [HUMMINGBIRDS’ WINGS] The thrumming of the tiny hummers' wings as they dart from flower to flower and hover to gather nectar is punctuated by the morning chorus of other birds. [DOVE COOING] A distant white-winged dove and the occasional insect. [INSECT BUZZES BY] Mark Seth Lender made this recording this summer at about 6 in the morning.

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: James McCarthy, Ann Carlson, Michael Mann, Sarah Leen

Reporters: Andrew Keys, Sarah Bromer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. The UN's latest scientific assessment of climate change says there's overwhelming evidence that human activity is heating up the planet. But humans are also acting to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

MCCARTHY: I think where we can see extraordinary progress is in cities around the globe. The cities have shown that it's not that difficult to reduce CO2 emissions. So where you're free from the partisan politics you can see this actually works.

CURWOOD: Also, toads mysteriously materialize after torrential rains in the Arizona desert.

BROMER: It sounded like [SOUND].

ROSEN: [SOUND]

BROMER: Yeah, like that.

ROSEN: I fully expected it to be nothing but Couch’s Spadefoot, because of their ability to use such short-lived water.

CURWOOD: Toads and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm. Makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

Humans Change the Climate

Hubbard Glacier in Seward, Alaska. The IPCC report outlines the outlook for glacial melt sea level rise in the coming century (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston this is Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or the IPCC, has finally released the first part of its fifth assessment. Every five years or so, more than a thousand scientists come together to consider the risks of human induced climate change, its potential impacts and the options for response. This first part looks at the latest scientific evidence. The findings on impacts and possible responses will follow next year.

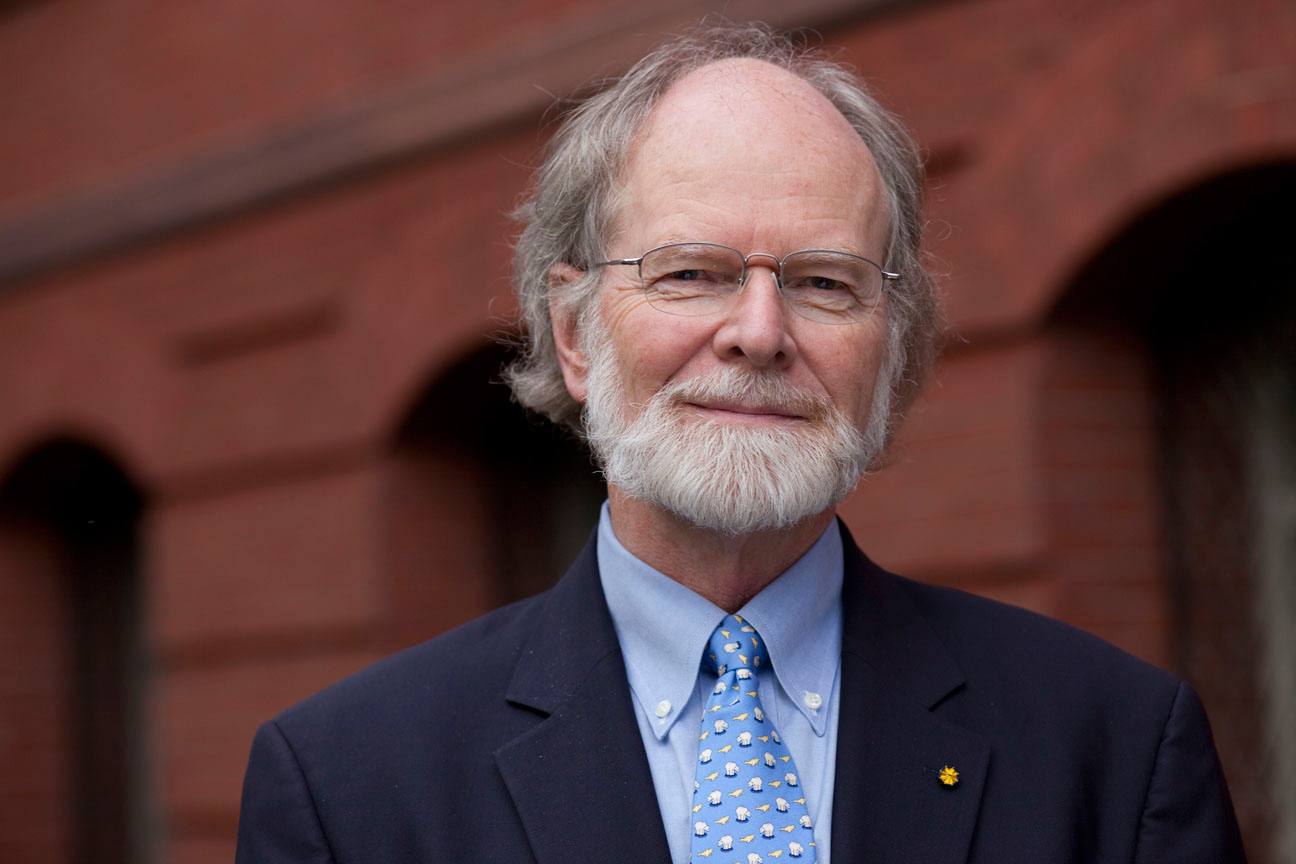

Professor James McCarthy, an oceanographic biologist at Harvard, was prominently involved in drafting and editing the past four IPCC reports, but is watching this one from the sidelines. I caught up with him at his lab at Harvard where he told me that scientists have again upped their certainty about global warming, declaring that it’s 95 percent certain human activity is causing the biosphere to warm.

Ocean temperatures continue to rise with less variability (image: Levitus et al.)

MCCARTHY: Everything we thought we knew about climate change we know even better now, and we have a longer record so we’ve seen more change, and we can be more confident of whether or not these reflect trends linked to climate or not.

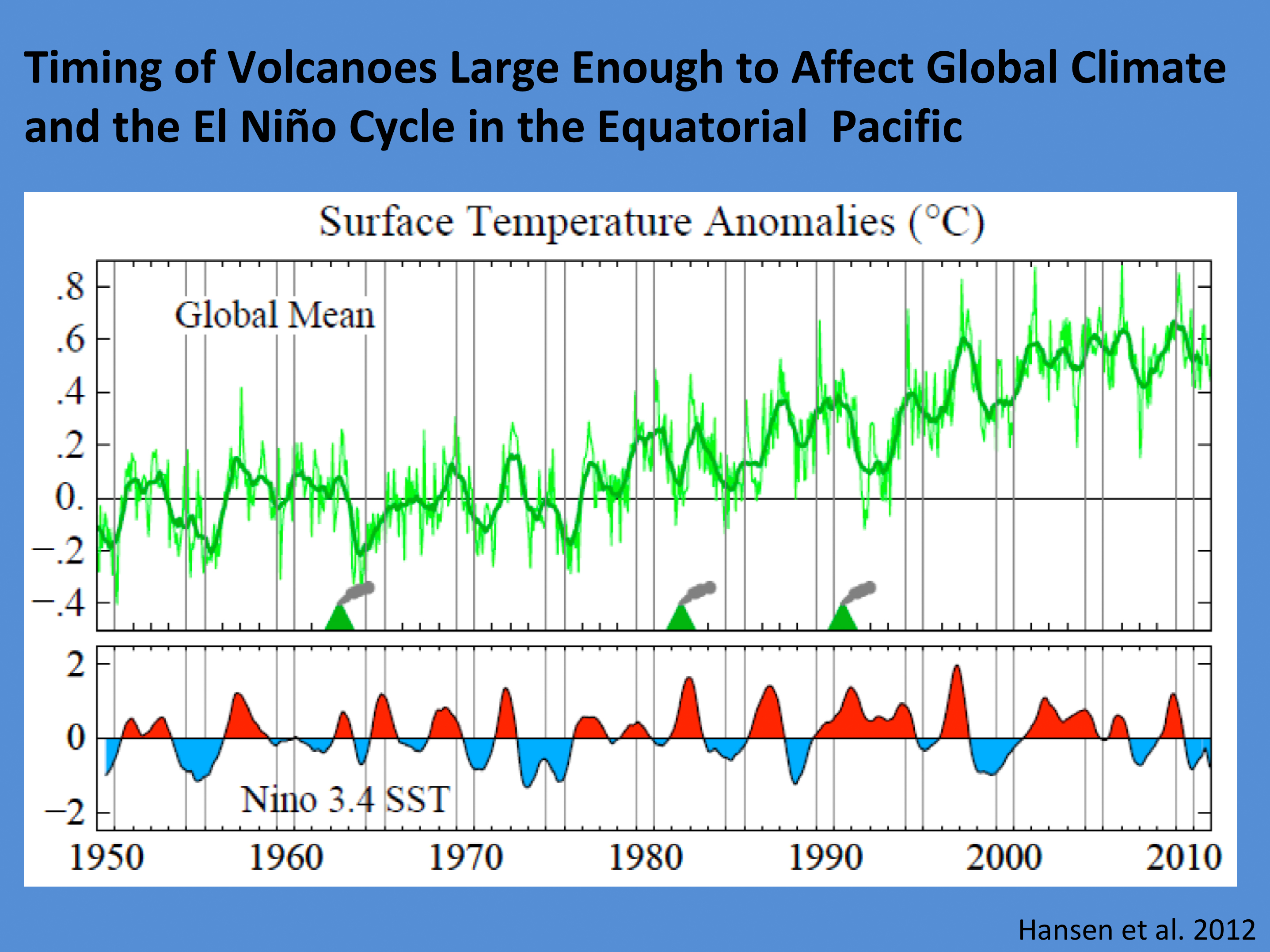

CURWOOD: Now, there’s a significant portion of the scientific part of the IPCC assessment that’s devoted to explaining why the rate of atmospheric warming has actually been going down. The rate, things are still increasing, of course, but the speed to which they’re increasing seems to be going down. What explanations do they offer?

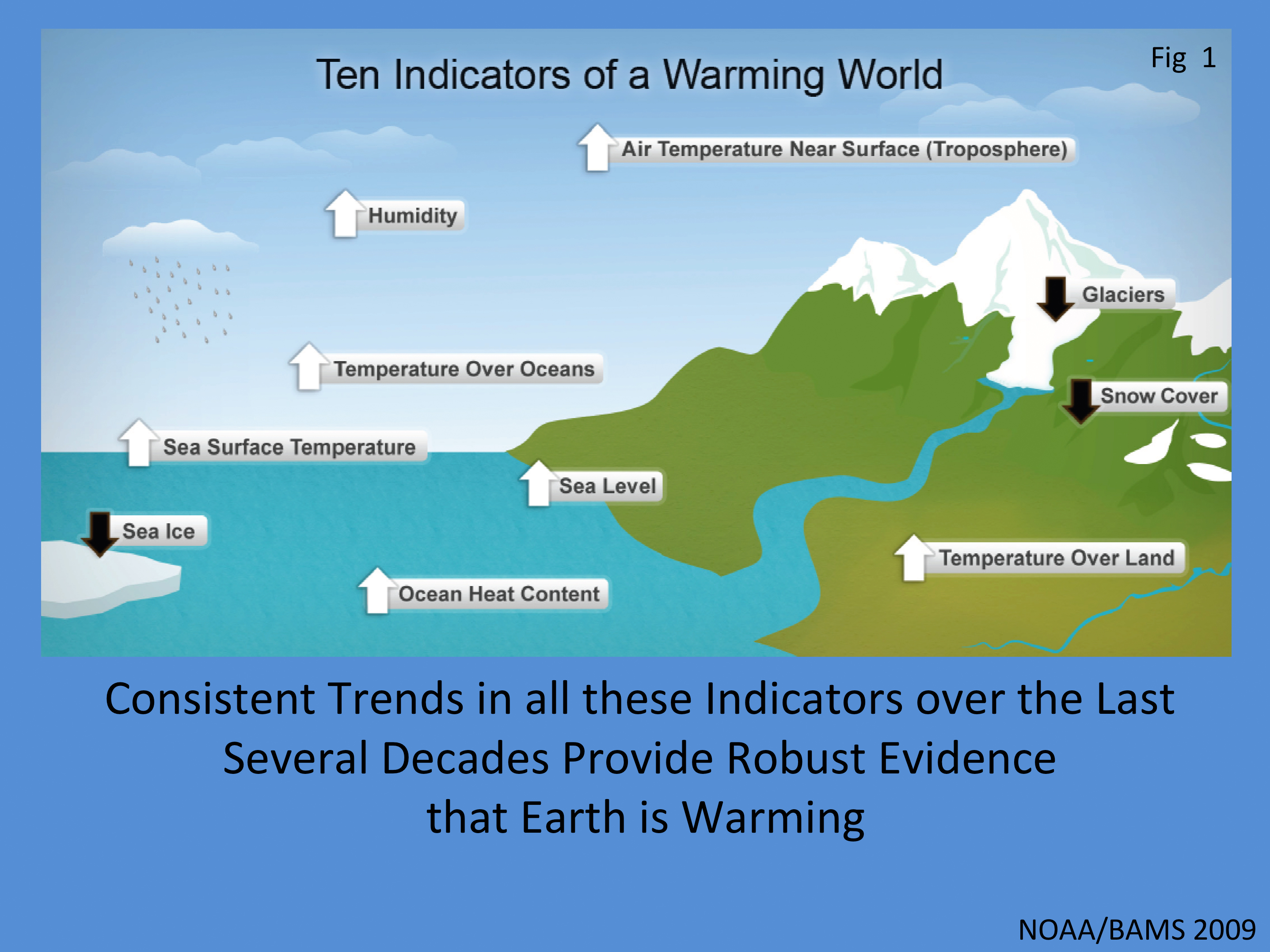

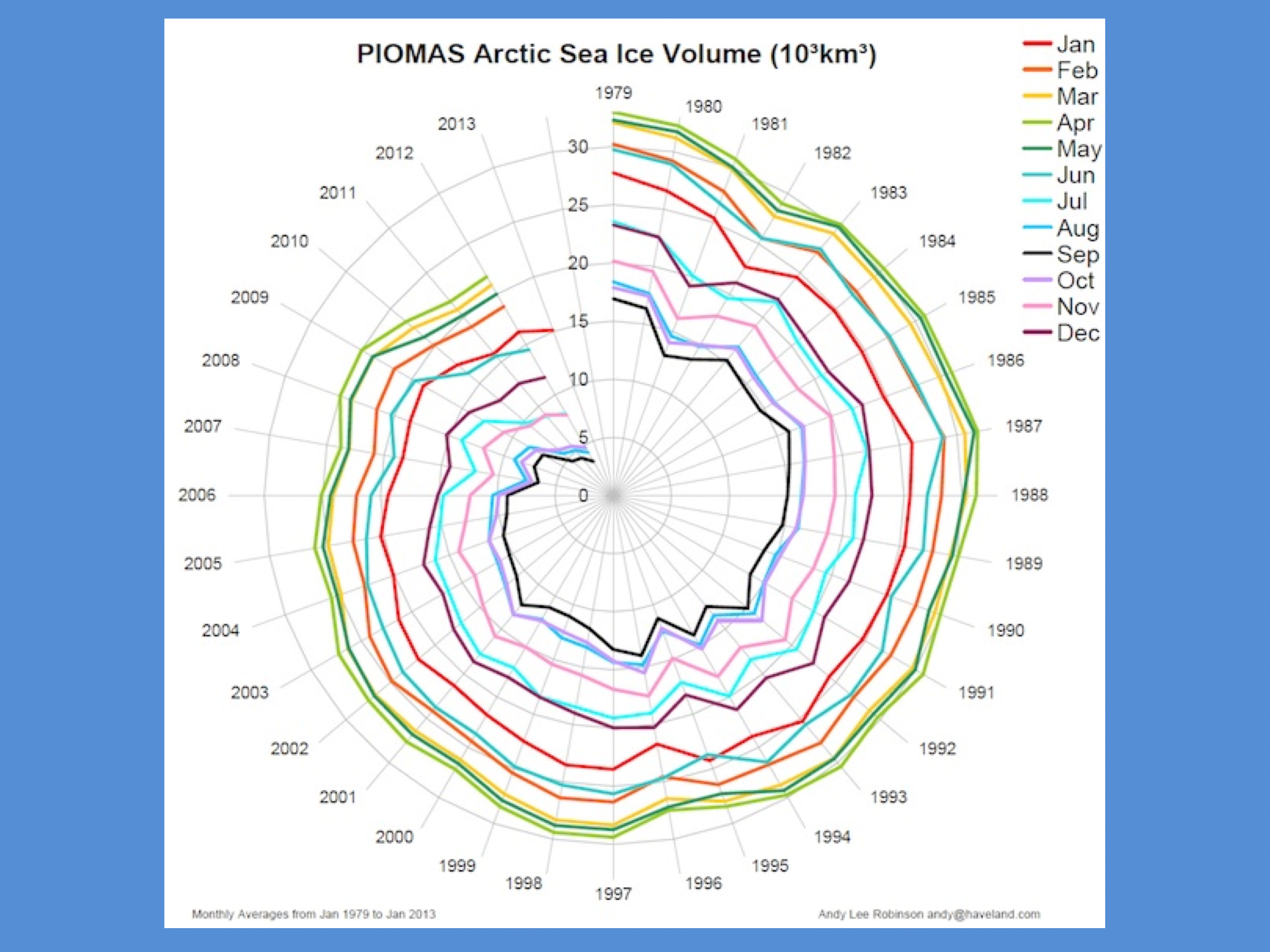

MCCARTHY: Well, first, I think it’s a mistake to focus on that. It’s the surface warming; it’s just one of arguably a dozen or so indicators of climate change. For a long time, climate scientists have realized that this global average surface temperature is something that’s easily expressed, and perhaps most easily followed, particularly for the non-scientists to get a sense of what’s happening. But if you look at the ocean, or you look at the Artic, you see there’s no slowdown. The Artic Ocean is continuing to lose ice. Right now, in the summer, the amount of ice in the Artic, that is the area with thickness is only about one-fifth what it was in 1980.

Ten indicators of a warming world (image: NOAA/BAMS)

The deep ocean over the past decade has continued to accumulate heat, it shows no slowing relative to the prior few decades. The ocean is changing, at depths as deep as 2,000 meters, which I can tell you, when I was a graduate student working in the north Pacific, if you had told me this would happen in my lifetime, I would have said, “That seems impossible.” Just think about how much heat that would be to mix all the way to a depth of 2,000 meters, yet we see this worldwide now. So records show us, about 90 percent of the additional heat that the Earth’s system has absorbed as a result of the greenhouse gases is actually in the ocean. That’s why, I think, if you get overly concerned about what surface temperature data are showing, you’re missing the big picture.

CURWOOD: What are the consequences of this deep ocean warming, do you think?

MCCARTHY: One of the consequences of the deep ocean warming is that it will be with us for a while. The ocean circulation moves slowly at depth, which means it will be hundreds of years before the ocean comes to equilibrium, which means over that time, the ocean will continue, as that heat mixes, to expand its volume the way mercury rises in a thermometer when the air temperature warms. So this is one of the reasons that sea level rise, regardless of what we do with emissions now, will continue to rise for a long time after we stabilize emissions.

Melting atop the Greenland Ice Cap in the summer of 2012 (image: NASA)

CURWOOD: Much is being made about how much more carbon we can safely burn at this point. Well, what do you think? What do you see as the carbon budget for the planet?

MCCARTHY: Well, this has been in the news a lot, and I think it’s a very intriguing argument. The great paper Rolling Stone that Bill McKibben laid this out, the great work that the Carbon Tracker is doing. It’s showing that, if all the reserves that have been identified for fossil fuels could conceivably be combusted to drive our fossil fuel economy were to be burned, the planet would be uninhabitable, and to say uninhabitable, well, that’s an overstatement for some, but in many cases, certainly areas that are well populated today - many of our coastal areas - will be uninhabitable.

The steadily shrinking volume of arctic sea ice (image: Andy Lee Robinson)

CURWOOD: Now, this part of the report is just a scientific assessment, but there will be policy recommendations as well. What kind of recommendations do you anticipate coming out of this assessment?

MCCARTHY: One of the frustrating things about the news coverage right now, frankly, is that it’s all about Working Group One, the science assessment. Working Group Two, which won’t be out for a few months, is the “so what?” question. So, I mean, should it really matter the Earth is warming or precipitation patterns are changing? Then following that, Working Group Three is the one that will look at policy options, mitigation strategies, cost benefit analysis...and I expect, Steve, that there will be far more specific recommendations about what could make a difference in terms of policy options that we’ve had in the past.

CURWOOD: So you’re not in this process this time, but if you were, what would perhaps be the most important recommendation you would make or want to have in this final report?

Harvard Professor James McCarthy (image: Harvard University)

MCCARTHY: Well, I think one of the most important things to note is that we have made substantial process in the last decade that has not come about as a result of international partnership or even leadership on the part of key nations. But I think where we can see extraordinary progress is in cities around the globe. The cities have shown it is not that difficult to reduce CO2 emissions. The city of Boston under Mayor Menino launched a plan in 2010 to reduce emissions in the city by 25 percent by 2020. It’s happening. This was not an unrealistic target, and other cities are doing the same. So where you're free from the partisan politics, where you’re free from the enormous enormous power of the fossil fuel industries that have influenced so many of our elected officials, when you have mayors who are accountable to their citizens, who know they have to deliver something, you can see this actually works.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think this latest assessment from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change will affect the international negotiations efforts to get a big deal worldwide to deal with this?

MCCARTHY: One of the parts that will certainly help is its treatment of sea level rise. When we completed the 2001 IPCC report, there was no indication that the mass of ice in Greenland would likely change much over the next several decades, but within two or three years we realized that that was wrong. And now that you see, clearly, the contribution of ice melt from Greenland, and increasingly Antartica to sea level rise, it’s possible to make a much better projection. In the 2007 assessment, the highest rates were anticipated under the scenario that would have us burning fossil fuels, basically business as usual, continuing without any reduction in fossil fuel combustion - it’s about two feet. Many studies since then, and these are what are being reflected in the new IPCC report, show that that number could be closer to three feet. And I believe that this will attract attention worldwide, and I do hope engender cooperation that we haven’t seen recently in the international arena of climate change.

CURWOOD: James McCarthy is Professor of Biological Oceanography at Harvard. Thanks so much for taking this time today.

MCCARTHY: Thank you, Steve, and I always look forward to your show.

CURWOOD: There are some explanatory charts and graphs on our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- IPCC website

- Prof. James J. McCarthy’s webpage

- Read a blog post by Prof. James J. McCarthy about the IPCC

A Challenge for Coal

Pollution from a coal-fired power plant (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Now key members of the United States Congress may deny the reality of global warming and dismiss the warnings of the IPCC, but the Obama administration is continuing to implement a Supreme Court decision to regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant. Power plants generate almost 40% of US greenhouse gas pollution, and now the EPA has once again proposed a set of rules to restrict emissions from new electric power plants. UCLA Environmental Law Professor Ann Carlson says how tough those rules look depends on the fuel that’s burned.

CARLSON: I think most people would acknowledge that for new natural gas plants, the new rules are relatively straightforward for power plant builders to meet. Coal-fired power plants are a tougher question because right now we don't have really off-the-shelf, super-affordable technology that can capture a lot of greenhouse gas emissions the coal-fired power plants emit. We do however have something called partial carbon capture and sequestration technology which takes carbon out of the air and puts it into the ground, but whether it's kind of readily available and affordable is the controversial question.

CURWOOD: Now, the Obama administration had proposed these rules for new power plants a while back but then I gather they got concerned about what would happen when they were tested in court, and this is a revision. How much of the rules changed since that first time around, and how bulletproof are they against litigation do you think?

Professor Ann Carlson, Faculty Director of the Emmett Center for Climate Change and the Environment at the UCLA School of Law (photo: UCLA)

CARLSON: Well, the prior rules treated natural gas facilities the same as coal-fired power plants, so they were subject to the same standard, and one legal concern about that approach in the old rules was that EPA hadn't previously treated coal-fired power plants identically with natural gas plants, and so there was some thought that was, just putting them in the same category made the rules legally vulnerable. But there's another legal question that would've been leveled at the old rules and will continue to be leveled at the new rules, and that comes back to this question of whether the technology exists to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to the level the EPA is proposing in its rules to meet the legal standard that EPA has to meet. It’s called ‘best demonstrated technology’. We have captured emissions and all sorts of things previously through technology like this, but not on the kind of scale that would be necessary for a coal-fired power plant to meet the EPA rule.

CURWOOD: So this rule is in regard to new power plants. What about existing? What will happen with rules for existing power plants?

CARLSON: So existing power plants...I think I want to stress pretty strongly...that’s really the place where we can make a really significant impact on the greenhouse gas emissions that the United States emits. Again, because we're not likely to build very many new power plants, we simply aren’t increasing demand for electricity very rapidly. The really interesting question is what happens to existing power plants. The Obama administration has made clear, and I believe it's legally required to, issue standards for existing plants. But how they do so is going to be a really big and really important question, and there are a bunch of legal reasons why it's actually complicated to predict exactly what EPA will do. On the one hand they could take a not very aggressive approach and not require very much of existing plants, or they could interpret their authority to take into account all sorts of things that they haven't previously taken into account in establishing standards for emissions control that include things like energy efficiency. If we could use energy efficiency to measure how much a power plant could reduce its emissions, or how much a utility overall could do so, we can see rules that are really quite significant in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

CURWOOD: So if a utility for example had this massive campaign and got everybody to put in LEDs or compact fluorescents, and set up smart metering so that the overall load for that polluting power plant was lower...that might count?

CARLSON: Well that's a question about whether it can count. Traditionally, we put the technology directly on the individual plant. Could we instead draft these rules in a way that is a little less rigidly focused on the plant and more focused on overall electricity consumption, and therefore make some choices that are actually more economical, what we call low-hanging fruit, right? Get everybody to weatherize their houses so they stop wasting electricity, get businesses to install energy-efficient equipment, encourage the purchase of energy-efficient appliances in apartments and houses and so forth. Can those count as rules for existing power plants, and that's really the big legal conundrum.

CURWOOD: Critics say these rules, proposed rule for new power plants, as well as the spectrum of the one covering existing power plants, is part of a war on coal. How do you respond to that?

CARLSON: I view these rules as a very necessary response to the problem of climate change, and coal and the firing of coal to generate electricity, is the most carbon intensive fuel for the production of electricity, and so there's simply no way for the US to dramatically cut its greenhouse gas missions without figuring out how to make coal-fired power plants either sequester their emissions or operate in a more efficient fashion, or to reduce energy consumption over all. So coal is going to have to play its part. Now, I wouldn’t call it a war on coal, but a war on greenhouse gas emissions, but it is absolutely the case that coal is a carbon intensive fuel and we need to do something about those emissions in order to get climate change under control.

CURWOOD: Ann Carlson is Faculty Director at the Emmett Center on Climate Change and the Environment at the UCLA School of Law. That’s so much, professor.

CARLSON: You're welcome, and thanks for inviting me.

Related links:

- Read about the EPA’s plans to regulate emissions from new powerplants

- Ann Carlson’s webpage

[MUSIC: Black Devil Disco Club “I Regret The Flower Power” from 28 After (Lo Records 2006)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...celebrating 125 years of a picture window on the world. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Christian Scott: “When Marissa Stands Her ground” from Christian Atunde Adjuah (Concord Music 2012)]

Science Note

A field of Brachiaria in cultivation in Colombia. (photo: Wikimedia Commons user Tortie tude.)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. In a minute, searching for elusive toads in Tucson, but first this note on emerging science from Andrew Keys.

KEYS: The grass potentially just got greener for agriculture.

Researchers have discovered a chemical in the roots of a tropical grass that may be key to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Farmers rely on nitrogen fertilizer to grow more robust crops. But plants actually make use of less than a third of the nitrogen in that fertilizer. Soil bacteria gobble up the rest, and convert it to nitrous oxide, a climate-altering gas, and nitrate, a compound that washes into waterways and can cause harmful algae blooms.

In the 1980s, researchers at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture in Colombia discovered a grass that grows well in low-nitrogen soils, even without fertilizer. It’s an African savannah grass called Brachiaria humidicola that’s commonly grown as feed for livestock. This year, the scientists got to the root of why this grass flourishes with little nitrogen. A chemical in Brachiaria’s roots inhibits soil bacteria from absorbing the lion’s share of available nitrogen. That means more for the plant, and less need for fertilizer.

Brachiaria is already a popular forage grass for livestock across the tropics. Now that they understand its potential to lower emissions and save money on fertilizer, researchers hope to harness the powers of this chemical to improve crop yields in staples like rice and corn.

That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. I’m Andrew Keys.

Related links:

- Grass gets greener: Nature

- International Center for Tropical Agriculture

Toads in Tuscon

Couch’s Spadefoot Toad (Photo: Reptilist Flickr Creative Commons)

CURWOOD: Now the US monsoon, the fierce and sometimes torrential summer rains in the southwest, has dominated the news lately because of devastating floods in Colorado. But in nearby Arizona, there's been a fairly normal amount of rainfall, creating the usual flooded streets and sudden ponds - prime breeding habitat for mosquitoes. And in the cities, local officials try to rid of the standing water, but for some desert animals those brief pools can mean the difference between life and death. From Tucson, Sarah Bromer has the story.

BROMER: I was out taking a walk one night after a summer storm in downtown Tucson when I heard a sound I’d never heard before:

[SOUND OF TOADS]

BROMER: It kind of sounded like a flock of sheep.

[SOUND OF TOADS]

BROMER: But that seemed unlikely, given that I only live a few blocks from the center of downtown.

[MORE CROAKING]

BROMER: So I followed the sound, to the edge of my neighborhood, where I found people gathered with flashlights.

[EXCLAMATIONS OF SURPRISE,]

BROMER: There, in a temporary drainage pond next to a shipping warehouse, were dozens of toads.

[TOAD SOUNDS]

BROMER: Now amphibians are pretty much the last animals you expect to find in a dry, dusty, desert town like Tucson, and nobody seemed to know much about them. So I called an expert.

ROSEN: So I’m Phil Rosen, and I’m a research scientist in Natural Resources and the Environment at the University of Arizona.

BROMER: I took Phil to the pond the next night, and we listened.

[SILENCE AND DISTANT TRAFFIC]

BROMER: But all we heard was…silence. The pond looked a lot smaller. We found tadpoles in the water, but no toads, so I tried to explain the sound to him.

BROMER: Yeah, it sounded like wwwaaaahhhh! [IMITATES SOUND]

ROSEN: wwwwaaaaahhh? [IMITATES SOUND] wwwwaaaaahhh?

BROMER: Yeah, like that.

BROMER: Phil was pretty sure that I’d heard Couch’s spadefoot toads.

ROSEN: I fully expected it to be nothing but Couch’s spadefoot, because of their ability to use such short-lived water. They’re uniquely explosive breeders with very short tadpole stages.

BROMER: He told me the toads spend most of their lives underground, emerging each summer for maybe only a few nights of frantic feeding and breeding. Their eggs hatch within hours, and only seven or eight days later the tadpoles become toads.

Couch’s Spadefoot Toad. (Photo: Tom Spinker)

ROSEN: It’s fastest metamorphosing species here, probably one of the fastest in the world.

BROMER: I thought Phil would be really excited to find prime toad breeding habitat in the middle of the city, but he wasn’t very excited at all. He told me that the water in the pond probably wouldn’t last long enough for the tadpoles to turn into toads.

ROSEN: This basin that we’re standing next to is designed to uh dry itself within three days. It’s too bad because it is like an ecological trap because it just seems really good for them but it’s… huh... It’s an attractive nuisance for them, basically. It brings them into breed in a place they can’t survive.

BROMER: Tucson’s building codes require all businesses to capture their run-off, so it won’t contribute to flooding, and then sink the water into the ground quickly, so it won’t breed mosquitoes. Here’s Phil Rosen again.

ROSEN: Well, you know, this sort of thing worries me, because it exemplifies the ability and the tendency of people to just keep modifying the environment, and making it more and more perfect for people, and, unfortunately, there’s less tendency for there to be little corners where water lasts for two or three or four weeks…and so I suspect there’s an ongoing, very steady decline of these species throughout most the city.

BROMER: Now you wouldn’t think mosquitoes would be a big problem in the Southwest. Tucson gets less than 12 inches of rain a year. But over half of it falls during what people around here call the monsoon season, in July, August, and September. It floods the streets and forms temporary pools all over the city. And when the water comes, so do the mosquitoes.

A monsoon storm heating up in Pima County, AZ. (Photo: Katja Schulz)

ACOBA: Mosquitoes really just need water and a warm blood source in order to thrive, so we do have that in Tucson, especially during the times of our monsoon, when we have a lot of rain.

BROMER: That’s Dr. Michael Acoba. He’s the head of epidemiology at the County Health Department

ACOBA: Well, the majority of the time, the mosquitoes we have, they’re just a nuisance, but since 2004, we had our first case of West Nile Virus here. The number of cases spiked one year to about 40 cases, but usually we see about 10-20 cases a year.

BROMER: So what if we want toads in our neighborhood, but not mosquitoes? According to Phil Rosen, it’s possible to have one without the other.

ROSEN: If a pond, let’s say, like this one lasted say on average 2 to 3 months, it would be so full of predatory crustaceans and insects, that it wouldn’t really produce any mosquitoes.

BROMER: To prove his point he took me to a nearby drainage basin, in a neighborhood squeezed between the freeway and the dry Santa Cruz riverbed. The basin was dammed up at one end with sediment and old tires, and its concrete sides were covered with graffiti.

At least 5 species of toads use this concrete drainage ditch for reproduction. (Photo: Sarah Bromer)

[TRILLING TOADS FADE IN]

BROMER: It was not a pretty sight. But it was full of toads.

ROSEN: So this is a highly engineered, concrete drainage outlet, and the mouth of it is blocked by flood debris, and so it’s formed a pretty deep pool, and right now there are two species of true toads breeding it. Those loud ones are Great Plains Toads and the more musical trill are Red-spotted toads.

[MORE TRILLING TOADS]

BROMER: We climbed down to the water and Phil pointed out all the tiny animals that eat mosquito larvae.

ROSEN: I’m interested in the invertebrates here. There’s all kinds of little beetles swimming around here whose larvae will eat mosquitoes. There’s a tadpole shrimp. There’s quite a few of them. Trying to see if there’s any mosquito larvae…because everyone would sort of expect there to be tons of mosquito larvae in a place like this, making it a public health nuisance. But with this number of aquatic invertebrates, mosquitoes might have a very hard time surviving here…and I’m not seeing any.

BROMER: The County Health Department here deals with mosquitoes by either eliminating standing water or treating it a larvicide. Jeff Terrell manages the vector control program for the department.

TERRELL: Well larvicide we use it’s usually like a—what they call a—BTI, which is a bacteria. Um we do use a larvicide oil which is more of a mineral oil with a surfactant that spreads over the water and keeps it, you know, keeps the larvae from breaking the water surface and breathing so they drown.

BROMER: Both BTI and mineral oil, if used correctly, are generally considered safe for toads and other vertebrates. But at least one study showed that BTI might sometimes target insects it’s not supposed to, and the oil kills several of the aquatic invertebrates that serve as natural pest control.

A drainage pond after summer rains attracts toads. (Sarah Bromer)

Phil Rosen suspects that the oil isn’t good for tadpoles, either. He’s been researching alternative solutions, and local officials have been open to his ideas. He’s been working with them to design experimental pools of longer-standing water that use invertebrate biodiversity to control mosquitoes.

ROSEN: So, I’ve been working to develop that it into kind of an art form…because I completely sympathize with people not wanting to live around lots of mosquitoes.

BROMER: He believes that in the long run his solution, though more complicated, will be the best one.

ROSEN: You know, if we simplify our environment, we’re going to end up with just the things we can’t deal with, diseases, and vectors, and things like that. We’ll either have to reengineer everything so there’s zero standing water, or we’ll have to try to live with the biodiversity and turn it to our ends and …let the kids growing up have something interesting to grow up with…

The same drainage pond three days later has dried up completely. (Photo: Sarah Bromer)

BOMER: I went back to the pond in my neighborhood a few days later, and, as Phil had predicted, all of the water was gone. Birds were pecking at the muck. I guess it wasn’t a good year for the Couch’s spadefoots of downtown Tucson. But maybe someday this pond will be reengineered …

[SOUNDS OF SPADEFOOT TOADS]

BROMER: …and stocked with the right kinds of invertebrates, which will allow us to have the best of both worlds: a neighborhood that’s rich with biodiversity and singing toads, and not too many mosquitoes. For Living On Earth, I’m Sarah Bromer in Tucson.

[MUSIC: Bobbi Humphrey “The Trip” from Fancy Dancer (Blue Note Records 1975)]

National Geographic 125 Year Anniversary

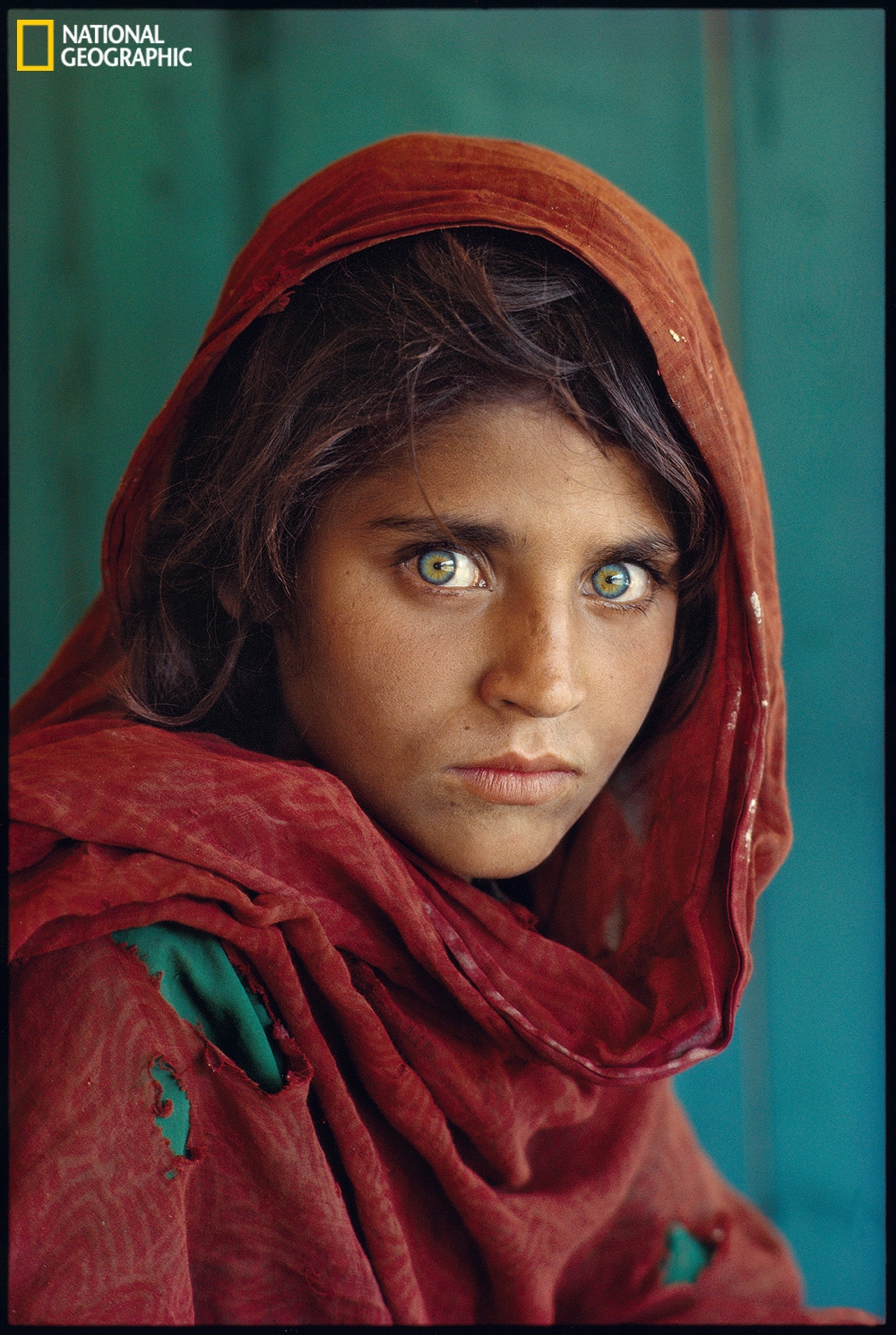

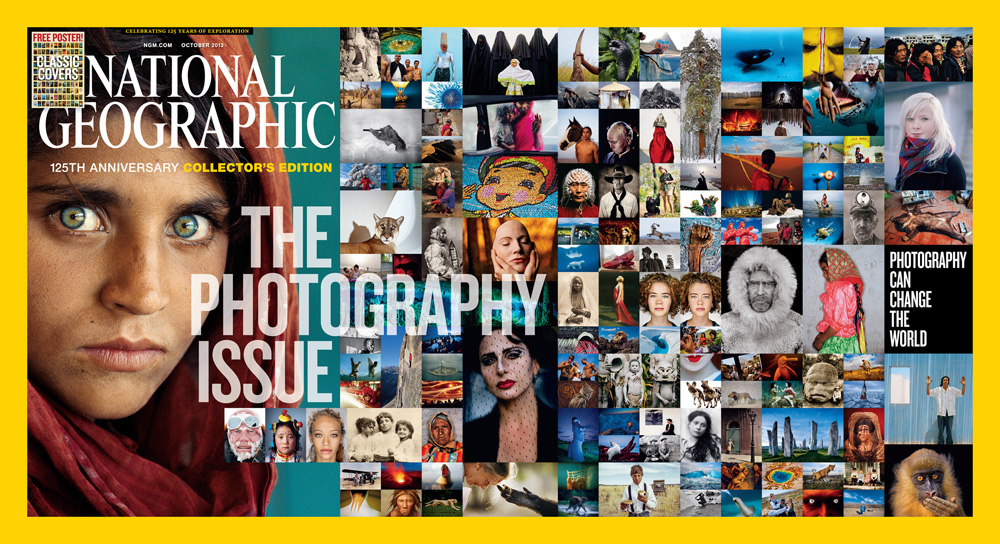

Steve McCurry’s iconic photograph of a young Afghan girl in a Pakistan refugee camp appeared on the cover of National Geographic magazine’s June 1985 issue and became the most famous cover image in the magazine’s history. It also graces the cover of the 125th anniversary issue (Photo: Steve Mc Curry from the October 125th anniversary issue of National Geographic magazine.)

CURWOOD: For armchair adventurers and nature enthusiasts alike, National Geographic magazine has been essential reading for generations. And in its October issue, the magazine is celebrating its 125th anniversary and revisiting some of its most iconic photographs - that haunting image of a young Afghani refugee girl is on the cover. Sarah Leen is the magazine's Director of Photography and joins me now to talk about the role of pictures in telling the National Geographic Society's stories.

2006 Columbia Glacier, Columbia Bay, Alaska. When James Balog first photographed the debris-streaked Columbia Glacier, its face had retreated 11 miles since 1980. That pace compelled him to launch the Extreme Ice Survey, installing cameras at 18 glaciers to witness climate change. (Photo: Extreme Ice Survey with Matthew Kennedy from the October 125th anniversary issue of National Geographic magazine.)

LEEN: The first issue in 1888 was pretty much like a little pamphlet almost, it was started as a scientific journal that reported back from explorers and scientists in that were sent out into the field. So it was just only text at the very beginning. I think that it was the following year that they had a map, but it wasn't until really about 1904 that we started really using photographs. There was an article that didn't come through and they had some pages to fill, and the president of the society had these set of images from Tibet, and they decided to publish those photographs. So it was kind of the first picture story and first series of images ever published, and some people were shocked and dismayed and thought it was just the end of everything.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, today National Geographic photographers are well-known to be, well, let’s call them intrepid. You know, they’ll do anything for a photo, come home with frostbite or mosquito bites. But I imagine those early days of the magazine must have been even tougher without the lightweight equipment that we have today.

2012 Columbia Glacier, Columbia Bay, Alaska. Iceberg-choked Prince William Sound reveals that the retreat of the Columbia Glacier is accelerating: It’s lost two more miles of ice in six years. And since 1980 it has diminished vertically an amount equal to the height of New York’s Empire State Building. (Photo: James Balog from the October 125th anniversary issue of National Geographic magazine)

LEEN: Yes, those early days were much more like an expedition where they would go with the whole team. There’s some famous photographs of Joseph Rock, who was an early explorer in China, and he would bring even, like, a bathtub. They would bring all kinds of stuff. It would be, like, 50 porters carrying things. Of course, now, it's much much different.

CURWOOD: Well, let’s talk about a few of the photographs that you featured in your 125th anniversary issue.

LEEN: Sure.

CURWOOD: You have a segment that features North Korea. There’s a picture in this layout that just jumps out. It shows a blackout in Pyongyang, North Korea's capital, but one thing remains illuminated. Would you describe that picture for our listeners please?

At dawn, portraits of Kim Il Sung and his son Kim Jong Il are still lit up in Pyongyang. Even during the city’s blackouts, electricity is reserved to light the flame atop Juche Tower. (Photo: David Guttenfelder from the October 125th anniversary issue of National Geographic magazine)

LEEN: This is a really wonderful image. It’s very blue. You're looking out across the city from another tall building, and it all looks dark, like you say, there’s a blackout except there is just one thing illuminated, which is portraits of Kim Jong Il and Kim Jong Un, the former leader and current leaders of North Korea, and it's just this very eerie-looking scene, but quite beautiful at the same time - very moody. I really like that picture, I’m glad you pointed that one out.

The extended cover of the 125th anniversary issue of National Geographic. (Photo: National Geographic)

CURWOOD: There’s another theme of this special edition, your anniversary edition of National Geographic, and that theme is ‘relate’, and I’d like to call attention to a really striking image of that segment. It's a couple in Afghanistan on their wedding day. The groom is 40, the bride about 11, and the caption says close to half of Afghan girls marry before they’re 18. But I think this has to be a classic case of a picture being worth a thousand words.

LEEN: Yes, Stephanie Sinclair who took that image, she has been working on the issue of child brides all over the world for a number of years. This particular image I find to be almost chilling when you look at it, this adorable little girl trying to imagine her being married to this guy. You say he's 40, but he looks like, older than 40, his beard, and kind of craggy, but this is the custom there. Photography can help you relate and connect to other people and get you care about things, and I think once you start getting people to care about things you can get them to get involved and maybe even help change the world, and I think that's definitely one of Stephanie's missions.

CURWOOD: We’re just about done, but, of course, I have to ask you...you have this chart that you call the naked truth.

LEEN: I knew this was...it was gonna be this. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: And let me read the text next to it. It says, “Everybody always mentions the nudity in National Geographic. For the special issue of photography we figured we should mention it too and document how much the magazine has actually published.” And you have these charts going back, looks like some time in the 1890s you published your first bare-breasted photo, you show the issue that had the most some time in 1912, um, what about this?

LEEN: Well, as a photographer you go out and you say you’re with National Geographic Magazine and two always things get said, ”Oh we have a basement full of those at home,” and the other thing that gets said often, mostly by guys, is, “I saw my first bare-breasted woman National Geographic.” And it was just kind of like, oh, there it is, and it was like, sort of, we’re kind of connected with that, like this is where people first saw, sort of, naked women, and when we were brainstorming ideas for the issue, I said, “Let’s get to the bottom of this. Let’s find out how actually many times this has really happened, and find that number.” So there was some poor soul who went through 125 years of National Geographic Magazines and counted them, and we came up with that 529 number.

CURWOOD: Now, today almost everyone has a pretty decent camera right on their phone with them all the time practically. What do you see as the role of everyday folks documenting the world now?

LEEN: I'm very excited about it. I mean, I'm one of those people, you know, I'm photographing with my phone all the time and posting to my Instagram feed, and we have a really robust Instagram feed ourselves. It's about 2.7 million people follow the Nat Geo instagram feed. It’s just an exciting time for photography in general.

CURWOOD: Sarah Leen is Director of Photography for National Geographic. Thanks so much for taking this time.

LEEN: It's my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: And keep on taking those pictures.

LEEN: We will!

Related link:

National Geographic: The Power of Photography

[MUSIC: Leonard Bernstein “Pictures At An Exhibition: Allegro giusto” from Mussorsky: Pictures At An Exhibition, Night on Bald Mountain (Sony Classical 1987 reissue)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars, a new book from a leading US climate change researcher who found himself on the barricades. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Aniceto Y Sus Fabulosos “Mi Gran Noche” from Cumbia Beat Vol. 1 (Vampisoul/The Orchard 2010)]

The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars

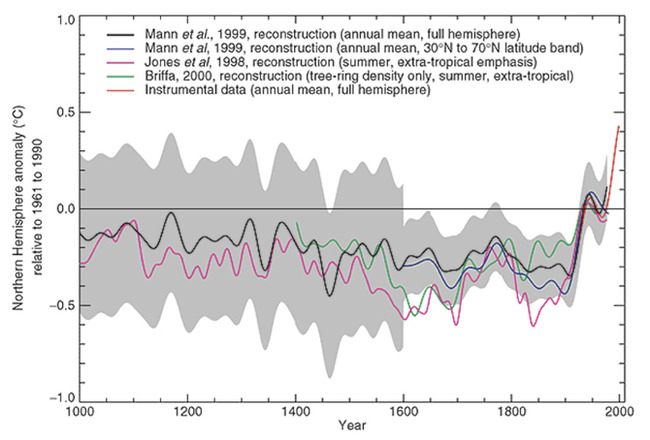

The now famous hockey stick graph shows a dramatic increase in temperature in the 20th century. (photo: Michael Mann)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

Michael Mann is a Professor of Meteorology at Penn State University and was a lead author of the third assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. His career has focused on quantifying the connection between human related greenhouse gas emissions and a warming planet.

Michael Mann looking for polar bears in Chruchill, Manitoba. (Photo: Michael Mann)

In 2009, he found himself at the center of a controversy that came to be known as "Climategate" when the emails of a number of scientists were hacked. Climate skeptics then selectively quoted the emails in attempts to discredit the scientists. Michael Mann was a major target, and now he’s written a book about that experience, it’s titled The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines. He says this wasn't part of the career he planned.

MANN: Well, I started out as a science nerd who simply wanted to be in the lab at my computer analyzing data, working on interesting problems. The last thing that I expected was that my interest in science would lead me into the center of this raging societal debate about human-caused climate change.

CURWOOD: So in your early days as a scientist, you came up with something that’s known as the hockey stick graph. What exactly is the hockey stick?

MANN: Well, we only have about a century of widespread thermometer measurements in the world. So we know the world has warmed by a little more than a degree Fahrenheit, but we don’t know how unusual that sort of warming might be in a longer term context without turning to other sources of information, so-called proxy records like tree rings, ice cores, corals, and so what my co-authors and I did in the 1990s was to take all the information available in these natural archives and use them to reconstruct the climate back into the more distant past, and what we found was the more recent warming was unprecented as far back as we could go, which was 1,000 years at the time, and the shape of the curve, which shows a long-term cooling trend from the medival era into the depths of the Little Ice Age, followed by a anomalous spike of the past two centuries, sort of resembles a well known sports implement - a hockey stick.

And the key take home message from this graphic is that that modern spike has no precedent as far back as we can go, and by inference it probably has something to do with what we human beings are doing. It became an icon in the climate change debate, and I almost instantly found myself a target for those seeking to discredit the science of climate change.

CURWOOD: Well, of course, hockey is a very competitive and body-checking sport.

Michael Mann with tree ring samples that can serve as proxy for ancient climate data. (Photo: Michael Mann)

MANN: [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: If you want to keep your front teeth, you probably don’t want to play hockey.

MANN: Well, that’s right. I’ve taken a few body checks in my time, but I’ve given back a few. I was initially quite reluctant to get into the fray, but I had no choice because I being subject to attack. There were pretty large forces out there, looking to discredit me, and so I decided I needed to fight back against that, and the only way to do that was to jump into the fray, to become involved in sort of the larger public debate over human-caused climate change, and ultimately, I’ve embraced that role. I can think of no greater calling than to be in a position to inform what may be the greatest societal challenge we human beings have yet faced.

CURWOOD: Now, the incident that came to be known as “Climategate;” in that incident, your emails were hacked just before the UN Climate Negotiations in Copenhagen back in 2009.

MANN: Right.

CURWOOD: How did you find out, and what happened?

MANN: Sure. So it was actually a criminal theft of emails of a university e-mail server in the UK, and hackers broke into the server, stole thousands of emails, and then what they did was particularly pernicious. They combed through those emails, and they cherry-picked individual words and phrases, and took them out of context and plastered them up all over the internet out of context to try to make it sound like scientists had been fudging the data.

CURWOOD: For instance?

MANN: So, for example, in one email, a colleague of mine refers to a ‘trick’ that used in a graph that he was preparing, and to the outside world, it’s easy to try to make that sound nefarious. Oh, ‘these scientists are playing tricks on you’...when in fact, if you’re a scientist or a mathematician, you know that a trick is a clever approach to solving a problem, like a trick of the trade - here’s the trick to solving that problem. And the journal Nature at the time editorialized about how ridiculous that it was that these, that the critics were taking perfectly innocuous words that were part of the scientific lingo, and then intentionally trying to mislead the public into thinking that it called into question the science.

And it wasn’t a coincidence that this happened in the lead up to the Copenhagen summit in December of 2009 which was the first opportunity for meaningful progress in dealing with climate change in years, and it isn’t coincidental that the various media organizations and groups that were promoting these false claims about what the email supposedly showed were typically associated with fossil fuel front groups, groups like the Koch industry, the Koch Brothers, the Scaife Foundation, fossil fuel industry front groups like the Heartland Institute. There was this sort of echo chamber of industry-funded climate change denial that promoted these false, these fake allegations against scientists onto the TV screens of major news networks, and it was all in an effort to derail the Copenhagen Summit of December of 2009.

Now, several years later, there have been nine different investigations in the UK and the US, including the National Science Foundation inspector general, NOAA’s, the Department of Commerce inspector general, they have all come to the conclusion that these emails did not establish any improperiety on the part of the scientists. Ironically, the only wrongdoing here at all was the criminal theft of those emails in the first place.

Michael Mann’s book The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars. (Michael Mann)

CURWOOD: Right after your emails and those other scientists were hacked, not long after, Senator James Inhofe, a Republican from Oklahoma, created a list of some 17 scientists that he believes should be prosecuted for perpetrating the ‘hoax’ of climate change as evidenced by those emails. What was your reaction to that?

MANN: Yes, I’m proud to say I was on that list along with the Presidential Medal of Science Recipient Susan Solomon. So these completely outrageous and false allegations that grew out of the stolen emails were used by the usual suspects like James Inhofe, who happens to be one of the largest recipients in the US Senate of fossil fuel money. It was used as an excuse to pursue a new round of attacks aimed at discrediting climate science and discrediting climate scientists.

That was soon followed by an effort by the newly minted Attorney General of Virginia, Ken Cuccinelli, who tried to issue a subpoena against the University of Virginia to demand all of my personal emails from the time I was at the University of Virginia, and it was clearly part of this concerted effort to try to find something they could use, to discredit me, to discredit the science, to discredit the hockey stick.

Fortunately, once again, there were people on both sides of the political aisle -- institutions, major institutions, scientific institutions, editorial boards -- that strongly denounced what they saw as a transparent effort to intimidate scientists whose findings might not be convenient to the special interests that fund Ken Cuccinelli’s campaigns.

CURWOOD: So what do polls today show in terms of public opinion, and the legitimacy about scientific concern about climate change?

MANN: Public acceptance of the basic reality of climate change, the fact that the Earth is warming, and the fact that it has to do with human activity, is as high as it has ever been, and that’s despite the concerted attack against the science, and I think that’s in part because people are actually seeing climate change now with their own two eyes. We are seeing the impacts of climate change collectively in various types of more extreme weather: that terrible flooding event we just saw out in Boulder, almost certainly that had a climate change component to it: Sandy, Hurricane Sandy, devastating meteorogical event, almost certainly had a climate change component to it. So people are seeing the effects of climate change directly, and so I think it becomes less and less credible when the industry-funded talking heads continue to denounce climate change as a hoax.

Unfortunately, there is still a large gulf between the public acceptance of the science -- maybe at its highest...maybe in the range of 70 percent of the public accept that the globe is warming -- and maybe only 50, 55 percent accept that its due to human activity. If you look at what the scientific literature says, 97 percent of experts in this field recognize that the globe is warming and that it’s due to human activities. So we have this huge gulf between 97 percent of the scientists, and maybe 55 percent of the public. That gulf exists because there has been a hundreds of millions of dollar disinformation campaign by the fuel interests to confuse the public about what the science has to say.

CURWOOD: Professor, before you go, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a group that you worked with a number of years ago, came out with their latest report recently, their fifth assessment...

MANN: Right.

CURWOOD: ...that shows an even more clear link between greenhouse gas emissions and climate disruption. Can you tell me about that?

MANN: Sure. I’d be happy to. They’ve upped the confidence level from ‘very likely’ to ‘extremely likely’. Scientists are willing to say that something is ‘extremely likely’very rarely. That’s a very high degree of confidence. It’s ‘extremely likely’ that the warming of the past half century is due to increased greenhouse gas concentration, and moreover that the associated melting of ice, the rise of global sea level, and the increase in various type of extreme weather events can be tied to that human-caused warming.

CURWOOD: Now, given what’s happened to you as a scientist, who started off just to be a scientist, what advice do you have for a young scientist entering this field?

MANN: It’s a great question. One of my greatest fears is that the attack against scientists might dissuade young scientists from going into this field. Fortunately, I think the attack backfired. I think what they’ve done is to raise awareness, especially among the younger generation...a generation that’s very engaged in outreach and communication that grew up with social media, and they’re very engaged and they like communicating and they see a role now here, as a scientist, to be directly involved in the effort to communicate your science, and to fight back against efforts by others to confuse the public about science. That’s one of the reasons I’m so optimistic that we will get past this current impasse that we have with our politics, about dealing with this problem in good faith, that in the near future we will see considerable progress as that younger generation becomes more and more involved in the discussion and in the policy process.

CURWOOD: Penn State Professor Michael Mann’s new book is called The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines. Thanks so much, Professor.

MANN: Thank you. It was my pleasure.

Related links:

- The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars

- Michael Mann Home Page

[MUSIC: Ben Allison “Tricky Dick” from Cowboy Justice (Palmetto Records 2006)]

The Quarry

Just below Lover’s Leap (photo: Rod Clark)

CURWOOD: There are some memories that won’t let us go, it seems, and then there are other memories that are all about letting go. Here’s writer Rod Clark.

Mysterious woods on the upper level (photo: Rod Clark)

CLARK: Children are playing hide and seek in the old limestone quarry at the edge of the village where I grew up. I hear them as I walk, their voices ringing high and clear, echoing off the high stone walls among the mysterious trees.

Near Deadman’s cave (photo: Rod Clark)

Crows complain, squirrels scold the invaders from the safety of green branches, and suddenly I am carried back to summer days in the 50s when my brothers and I played “Scatter” and “Capture the Flag” on the two wooded levels of the quarry, remembering how we crept among the sumac and the shadows of boulders, how honeysuckle perfumed the air, and how once I saw a possum hanging by its tail in the cool shade of a Catalpa. And I remember how we named the secret places of our playground: “Pirates Path,” “Lover’s Leap,” “Dead Man’s Cave,” and most marvelous of all, “Cool Cave,” which possessed in its depths a limestone nook where you could keep a bottle of Coke cold even in the heat of summer…

The entrance to the cool cave (photo: Rod Clark)

And as I ascend the path to the uppermost ridge to look down upon a world mapped by children, some of whom are no longer alive, a small boy pops out of the brush in front of me, his eyes wide, burrs tangled in his hair. “Are there any pirates down there?” he demands breathlessly. But I am no longer of his world and cannot answer him. Without waiting for a reply, he plunges into the green realm below. I hear the rapid patter of his feet descending to the second level punctuated with improbable leaps and bounds, and suddenly I realize what it is I’ve been seeking when I make the pilgrimage to the old quarry.

Pirates Playground, lower level (photo: Rod Clarke)

Because it is my childhood that is racing away from me, down the steep pathway, among the mysterious trees.

Quarry wall on the upper level (photo: Rod Clark)

CURWOOD: Rod Clark lives and writes in Cambridge, Wisconsin. He's the editor and publisher of Rosebud magazine, and he took some pictures of the old quarry, they're at our website LOE.org.

Related link:

Rod Clark is the editor of Rosebud Magazine

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell “The Pioneers” from Good Dog, Happy Man (Nonesuch Records 2000)]

[SOUNDS OF BIRDS AND HUMMINGBIRDS’ WINGS]

CURWOOD: And we leave you this week with writer Mark Seth Lender, and recordings he captured of hummingbirds in Madera Canyon, Arizona.

[HUMMINGBIRDS’ WINGS]

The thrumming of the tiny hummers' wings as they dart from flower to flower and hover to gather nectar is punctuated by the morning chorus of other birds.

[DOVE COOING]

A distant white-winged dove and the occasional insect.

[INSECT BUZZES BY]

Mark Seth Lender made this recording this summer at about 6 in the morning.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Andrew Keys, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of Red Tomato, supplier of righteous fruits and vegetables from northeast family farms. www.redtomato.org. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth