January 25, 2013

Air Date: January 25, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Obama's Climate Promise

View the page for this story

In his second inauguration speech, President Obama called for urgent action to address our warming climate. Van Jones, former White House green jobs advisor and current director of Rebuild the Dream, joins host Steve Curwood to discuss how Obama can turn words into action. (07:55)

Obama Cites Religious Commandments to Act on Climate Change

View the page for this story

In calling for action on climate change, President Obama's speech claimed God has commanded us to care for the planet. Steve Curwood talks about how Obama’s religious rhetoric fits into climate change and politics with Richard Cizik, President of the New Evangelical Partnership for the Common Good. (06:40)

Mercury Dangers Around the World

View the page for this story

A new report finds hotspots of unsafe mercury levels world wide. David Evers, chief scientist at the Biodiversity Research Center tells host Steve Curwood that millions of people rely on fish with unsafe mercury levels as their principle source of protein. (06:10)

A New International Treaty on Mercury

View the page for this story

UN Delegates from over 140 countries make a deal for a treaty to limit world wide mercury emissions. David Lennett, senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, attended the meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, and tells host Steve Curwood that the treaty is a step in the right direction but could have been stronger. (05:05)

BirdNote ® Barred Owl

/ Mary MacCannView the page for this story

As the frigid long nights of January grip much of the country, Mary MacCann has an unexpected encounter with a Barred Owl. (02:10)

Research Update on the Impact of BP Oil Spill

View the page for this story

More than 1,000 scientists and government officials recently met in New Orleans to share the latest research on the effects of the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Host Steve Curwood talks to Mark Schleifstein, a reporter for NOLA.com, the Times Picayune, about what scientists have learned since the largest oil spill in US history. (06:15)

America's Bats on the Brink

View the page for this story

Bats should be hibernating this time of year, but winter visitors to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park have spotted them flying around in the middle of the day. Scientists suspect they may be infected with white nose syndrome. Katie Gillies, Imperiled Species Coordinator at Bat Conservation International, joins host Steve Curwood to discuss the state of bats in the United States. (06:35)

Can Prairie Dogs Save Mexico's Prairie From the Desert?

/ Ari Daniel ShapiroView the page for this story

There were once billions of black-tailed prairie dogs across the prairies of the West and Mexico. Today there is only a fraction of the original population left but activists in Mexico are working to bring back the prairie dogs and help restore the prairie along with them. (05:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood GUESTS: Van Jones, Richard Cizik, David Evers, David Lennett, Mary McGann, Mark Schleifstein, Katie Gillies REPORTERS: Ari Daniel Shapiro

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. The President makes action on climate change the centerpiece of his second inaugural to the delight of some.

JONES: I was really, really happy to hear him taking on the issue. You know, he will be judged harshly 20 years from now, 30 years from now, if he has done nothing on the biggest threat I think that humanity faces – runaway catastrophic climate chaos.

CURWOOD: But the President can’t count on Congress. Also a Mexican scientist unravels the mystery of why some prairies turn to desert. Something was missing.

CEBALLOS: It was mind-blowing because all along the horizon there were prairie dogs and prairie dogs and prairie dogs. And the next day, we saw badgers. Badgers are really rare in Mexico. Golden Eagles are really rare in Mexico, but we saw more than 20 there in one single day.

CURWOOD: The climate, prairie dogs and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[THEME]

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: “Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm.

Obama's Climate Promise

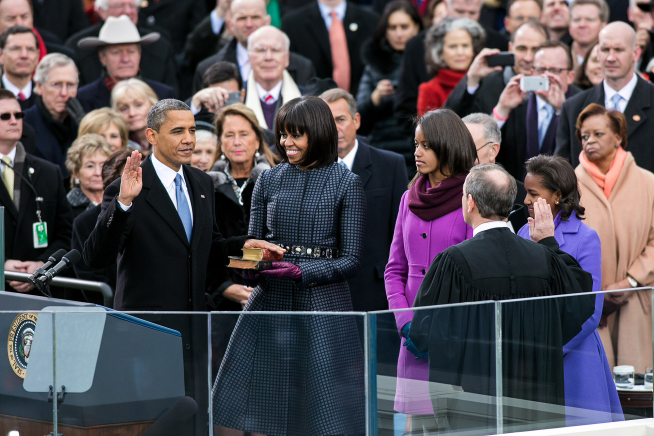

Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts administers the oath of office to President Barack Obama during the inaugural swearing-in ceremony at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., Jan. 21, 2013. First Lady Michelle Obama holds a Bible that belonged to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and President Lincoln’s Bible. Daughters Malia and Sasha stand with their parents. (Official White House Photo by Sonya N. Hebert.)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. President Obama has pledged to fight climate change before, but as he spoke to the nation shortly after taking the oath of office on January 21st, he made climate defense a central goal his second term.

OBAMA: We, the people, still believe that our obligations as Americans are not just to ourselves, but to all posterity. We will respond to the threat of climate change, knowing that failure to do so would betray our children and future generations. [APPLAUSE] Some may still deny the overwhelming judgment of science, but none can avoid the devastating impact of raging fires and crippling drought, and more powerful storms. The path towards sustainable energy sources will be long and sometimes difficult. But America cannot resist this transition; we must lead it. We cannot cede to other nations the technology that will power new jobs and new industries, we must claim its promise. That’s how we will maintain our economic vitality and our national treasure - our forests and waterways, our croplands and snow-capped peaks. That is how we will preserve our planet, commanded to our care by God. That’s what will lend meaning to the creed our Fathers once declared.

Former White House special assistant for green jobs, Van Jones (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Van Jones served President Obama in the beginning of the first term as a special assistant to green jobs. He’s now president of the organization, Rebuild the Dream.

JONES: I was really, really happy to hear him taking on the issue. You know, when you talk to this president or the administration, climate and energy are always number three or four, somewhere in the top five but never actually gotten around to. And I think it’s going to be number one, though, 20 years from now, 30 years from now. We will look back on a president who ran first on clean energy, on green jobs, on climate solutions in the first term, and did not deliver. And so I was happy to hear him going back to the things he ran on originally. And I think that, frankly, when you look at Superstorm Sandy hitting New Jersey and New York so hard, you look at this dust bowl forming in the middle of the country because of the drought, and you look at the wildfires that have just scorched the west, it’s really impossible not to talk about climate solutions if you really want to deal with what the American people are going through.

CURWOOD: Now the conventional wisdom is that the Congress is not likely to do a lot about climate in the near future. So as head of the Executive Branch of US government, what can President Obama do in this new term that he has if he wants to, and I’m quoting him here, “slow the rising of the oceans”?

JONES: Well, there’s three things he can do without Congress. Number one, he can refuse to approve the Keystone Pipeline which will let the tar sands go all around the world. The tar sands are this big carbon bomb up there in Canada. The scientists say if we burn all that super dirty fuel, it’s game over for climate. In order for the tar sands to come out of Canada, the US has to approve a pipeline. He can say no to that pipeline, number one. Number two, he can be tougher on our existing coal-fired power plants, which are a real source of greenhouse gases that NRDC and other groups are pushing for him to use his authority through the EPA, through the Clean Air Act, to cut carbon out of our existing coal-fired power plants.

CURWOOD: And number three?

JONES: Well number three, he can go to China. There is a big environmental catastrophe happening in China, not just carbon emissions, but just pollution, period. There are now protests in China from the grassroots, not just about labor conditions, but about air quality. China and the US are the biggest polluters. Frankly, pollution from China is now blowing into California where I live. They should sit down together and come up with some kind of agreement going forward. That would give him two years to build towards that summit, to do an educational role for the country, and after the midterms, since he’s got a better Congress, he’d be really in a good position to move aggressively and do something about this. He will be judged harshly 20 years from now, 30 years from now, if he has done nothing on the biggest threat I think that humanity faces – runaway catastrophic climate chaos.

CURWOOD: Now the governor of Nebraska has just approved the passage of the Keystone XL Pipeline through his state. How much of an environmental litmus test for President Obama is the Keystone question?

JONES: The Keystone Pipeline is the environmental litmus test for this President, for the new generation, the rising generation of environmentalists in particular. This is their first big fight on the environment. It was their first big victory more than a year ago. If the President takes that victory away from them, he is going to break the hearts of an entire generation of young people, whom he’s expecting to stay in his coalition through the midterms and beyond, and I think he should do the right thing by them, but also, frankly, do the right thing not just by the young people today, but by their children and their grandchildren. The tar sands are the dirtiest, most dangerous fuels on Earth. They should not come out of the ground. They certainly should not come through the United States. It’s not just a litmus test issue, it’s a leadership issue. Is he willing to match his rhetoric with deeds? And we’ll see very soon if he is.

CURWOOD: So, in other words, if he goes ahead with the Keystone...to use the colloquial...his talk at the inauguration about helping to fight climate change is just a bunch of jive?

JONES: Well, there’s probably some newer hipper language, but not fit for radio (laughs). My view, and I think the view of a lot of people is that there is one thing he can do, it is totally up to him, and in fact, Secretary of State Kerry, once he’s confirmed, to make a decision that could impact the direction of the climate on this planet forever, and he should make the right decision. And it’s very easy, unfortunately, to stand up and talk about America the beautiful, it’s going to take some courage to defend America’s beauty from the oil spillers and the mountain top removers and the Keystone Pipeline layers and all those people...and that’s what he’s going to have to do if he wants to secure his legacy.

CURWOOD: Now President Obama used to be your boss, he hired you at one point. From what you know of him, what do you think his decision on Keystone is going to be?

JONES: I think right now he would probably be inclined to approve the pipeline, especially given his setback of the Republican governor now reversing course, and I think he also will listen to his base. So I think it’s a question of the base now has to step up. I think he is going to have to be persuaded on the merits both politically, in terms of science, in terms of policy, to do the right thing. And I think the same time as I say that, I do want to stress, he is a President who listens. He has proven to be a President who takes his base very seriously, when the base gets vocal and gets insistent. That was true on immigration. It was true on marriage equality. It’s been true on the Keystone Pipeline up until now. It can be true again.

CURWOOD: Van Jones is founder and president of Rebuild the Dream and a commentator for CNN. Thanks so much, Van.

JONES: Thank you very much too.

Vice President Joe Biden and Dr. Jill Biden walk in the inaugural parade along Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., Jan. 21, 2013. (Official White House Photo by Lawrence Jackson)

President and Mrs. Obama stroll down Pennsylvania Avenue after the inauguration. (Official White House photo by Pete Souza)

The President, Vice President and their spouses Michele Obama and Dr. Jill Biden review troops after the Inauguration (Official White House photo by Rick McKay)

As many as one million people came to the Mall to here President Barack Obama deliver his inaugural address at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., Jan. 21, 2013. (Official White House Photo by Chuck Kennedy)

Related links:

- Text of the president’s inaugural address

- Video of the inauguration

- More about Van Jones

- Fred Krupp comments

Obama Cites Religious Commandments to Act on Climate Change

The president invokes a divine commandment to care for the earth. (Official White House Photo by Lawrence Jackson)

CURWOOD: Now in American political speechmaking, “God” is rarely mentioned beyond the almost obligatory, “God Bless America” at the conclusion. But as he spoke in front of the Capitol, President Obama invoked a divine commandment to preserve our planet. So we asked the Reverend Richard Cizik, president of the New Evangelical Partnership of the Common Good and the former vice president of the National Association of Evangelicals, to talk with us about how the President’s religious rhetoric fits into climate change and politics.

CURWOOD: Reverend Cizik, welcome to Living on Earth.

CIZIK: Hi, Steve.

CURWOOD: So why do you think President Obama decided to tie religion and climate change together in his second inaugural speech?

CIZIK: Because he needs to make that connection. In my estimation, there is a contingent of denialists, denialists in the religious community who push back against this. And so actually putting it in the God context makes a whole lot of sense for the President.

Rev. Richard Cizik, President of the New Evangelical Partnership for the Common Good and former Vice President for Governmental affairs of the National Association of Evangelicals.

CURWOOD: So why do evangelicals see climate change as their issue?

CIZIK: We believe God said to care for the Earth. From the beginning of the bible in the Book of Genesis all the way to the last book of the bible, of Revelation, we know that God said, first of all, “care for it, protect it, till it,” and then all the way in the last book he says, “I will destroy those who destroy the Earth.” Now that’s an imperative.

CURWOOD: So how widespread would you say is evangelical support for action on climate change now?

CIZIK: Some of us have been speaking about this for a decade. And while most evangelicals, I think, recognize the priority of taking action, they don’t always agree with the methodology of doing it. We saw that over the cap and trade debate a few years ago. But with the general challenge of addressing this issue of the environment, and of climate change, I think you’d get probably three-quarters of all evangelicals saying, “yes, we should do that.”

Protesters opposing the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: So, when you say three-quarters of all evangelicals in this country, generally, are in support of action for climate change, how many folks are we talking about here?

CIZIK: Well, evangelicals are one-quarter of the adult voting population of America, so if you count children, then you’re talking about one-third of Americans. So you’re really up to, if you count everyone, a hundred million people. Because we now are a nation of now more than 300 million people. So you’re talking about a huge swath of the American public.

CURWOOD: So tell me, to date, how much have evangelicals involved themselves in the politics of climate change?

CIZIK: A lot of evangelical leaders were involved in the cap and trade debate back in 2010, and we know that we now face a challenge that’s worse, last year being the warmest ever. And we still have a Republican party that’s pushing back and is resisting. We know that the Congress that was elected in 2010 included at least 80 to 100 house members in the Republican Party who are to one degree or another resisting the President on climate change action. So the Republican evangelicals are the ones that really need to join this. That’s why voices among evangelicals such as mine, frankly, are really important.

CURWOOD: How much do you think evangelicals are going to push their usually Republican Congressmen for more political progress on climate change in these next four years?

CIZIK: I think you’re going to find, thousands, tens of thousands, who are doing that. Some of us are even willing to risk arrest through civil disobedience. We were at the White House just a week ago - the Secret Service wouldn’t arrest us, to be quite frank, they didn’t want to do so right before the inaugural. But there are those leaders within our movement who want to raise this issue as a prioritized issue, something that we either succeed on or don’t in this administration as a test of, well, the whole success of the administration. That’s how important it is to us.

CURWOOD: You were at the White House? What was going on at the White House?

CIZIK: We had a pray-in and an interfaith gathering. It’s the interfaith action on climate change movement. And we’ll be back, joined by others led by Bill McKibben and the 350 movement, on February 17. That’s President’s Day. We did it last week because it was Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. And he, of all people, is an example to the nation of civil disobedience. And so of all things...praying at the White House, getting yourself arrested...but we’re not going to step back. We’re going to continue to raise this issue before the American public.

CURWOOD: Well praying and sitting-in and getting yourself arrested sounds like the civil rights movement to me.

CIZIK: It is. I have called this - and African American leaders have seconded it - as this is the civil rights issue of the 21st century. Not just for blacks and other minorities here in America, but for the people around the globe, the tens of millions who are being impacted already by climate change. And so, this isn’t something that might happen...it already is. And if we’re not willing, I say, as religious leaders to risk arrest at the White House for praying, then how do we ever expect the rest of the public to listen to us?

CURWOOD: So churches, of course, have a powerful ability to organize and motivate people. What ways do they plan to take action on climate change outside of the political spectrum?

CIZIK: We know that individuals have to change the way they live. But in addition, our churches have to change. That may mean they adopt the Energy Star programs to reduce energy, and we know that churches are doing that already. So there are many different levels other than the political here in Washington in which people need to act. It may be that the President chooses to use his executive power to push to action this time around knowing what happened to cap and trade. Well then, well and good. We’ll support him. We’ll support the EPA. However it happens, you have to have political push that accompanies the other individual community acts.

CURWOOD: Of course you’re leading evangelicals...what do you say to atheists about this?

CIZIK: We need them as much as they need us. We, the people of America, means everybody. It means, increasingly, the so-called nones, that is, those who profess no faith, which are now 20 percent, according to the most recent Pew polls. And we need them as much as they need us together to do this. And so, while I think this is a uniquely religious challenge, they would say it’s a uniquely human challenge. And I would say, absolutely, you’re right. So we’re all in this together and we have to do it together.

The west front of the US Capitol as President Obama speaks (Official White House photo by Lawrence Jackson)

CURWOOD: Richard Cizik is president of the New Evangelical Partnership for the Common Good. Thank you so much, Rich..

CIZIK: My pleasure, Steve.

CURWOOD: For more reaction on the President’s promise on climate change, including the views of Fred Krupp, head of the Environmental Defense Fund, head on over to our website. It’s LOE.org.

Related links:

- More on Richard Cizik

- The New Evangelical Partnership for the Common Good

- Fred Krupp Comments

- Video of President Obama’s inauguration speech

[MUSIC: Quicksilver Messenger Service “Mona” from Happy Trails (Capitol records 1968)]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, quicksilver has finally met its international match. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ernest Ranglin: Papa’s Juice Bag” from memories Of Barber Mack (Island Records 1996)]

Mercury Dangers Around the World

Small-scale gold miners add mercury to fine particles of gold. The gold binds to the mercury and can then be easily sifted out. (Biodiversity Research Institute)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Mercury, or quicksilver, is one the strangest heavy metals. It’s a shiny liquid at room temperature, and ancient alchemists were intrigued by its ability to dissolve other metals, including gold and silver, but not iron. But the ancients didn’t understand how toxic mercury is, especially to the brain and kidneys, and even fairly recently, it was widely used in medicine, including thermometers, dental fillings, and vaccines. It’s also abundant in coal, and with coal burning power plants on the rise, along with mercury-based gold mining, there are now dangerous levels of mercury pollution worldwide. That’s according to David Evers, executive director of the Biodiversity Research Institute who spoke to us from Geneva. Mr. Evers and his colleagues recently tested mercury levels around the world, and produced a report called “Global Mercury Hotspots”.

EVERS: We found mercury to be very ubiquitous in the environment. We found it in the marine ecosystems, in freshwater ecosystems, we found elevated levels in the northern hemisphere, as well as the southern hemisphere. So that was the interesting finding from this, is that wherever we looked, we found mercury to be quite elevated. Some of the places that we found especially elevated are in eastern Asia, in India and China in particular, as well as Europe in the Mediterranean Sea, and parts of South America.

CURWOOD: What’s the source of all this mercury in the environment worldwide?

EVERS: I think there’s two categories. Thirty-two percent of the emissions are from small-scale gold mining. So that’s the use of mercury to amalgamate with gold while you’re in the field, and to burn that mercury off so you have gold left in the bottom of your pan. That burning of that mercury and that release into the air by 20 or more million people is adding to the mercury emissions into the global pool. And the second piece is the coal-fired power plants. So the burning of coal...in some ways you’re burning in an instant potentially thousands of years of mercury deposited in that piece of coal by nature. So those are the two sources of mercury that are probably most problematic at a time at a global level.

CURWOOD: In the US, of course, there are not a lot of people practicing small scale gold mining, so is it safe to say most of our exposure in the US, the mercury is coming from fish...and could you please then explain that mechanism of exposure?

Fish are the principle source of protein in many developing countries. Researchers worry that millions of people are consuming mercury at unsafe levels in the form of fish. (Biodiversity Research Institute)

EVERS: Sure. The exposure for an average person in the US is primarily through methylmercury in fish. It’s the larger organisms that live long that are on the top of that food web that are most problematic. And a lot of times you’ll see in the newspaper or wherever and you’ll hear about tuna and swordfish, and it’s very true. Those are species that are long-lived and are on top of that food web that carry enough methylmercury in their bodies that if we eat them regularly, then that can increase the mercury levels in our own bodies to troublesome levels.

Some tuna species are known to be exceptionally high in mercury and are not safe for consumption. (Biodiversity Research Institute)

CURWOOD: So if someone is concerned about fish that has mercury in it, what should one do? Is there a difference between wild-caught and farm-raised, or a difference between ocean and freshwater?

EVERS: First, fish is a very good resource for us to use, and we have to be smart about our choices and our picks. Generally, farm-raised fish are lower in mercury than wild fish, and some fish have higher mercury levels in their bodies, but they may have very good omega-3 fatty acid levels in their body. So sometimes there could be tradeoffs in choosing which fish you want. If you want to eat fish low in mercury, and high in omega-3, salmon and herring are very good for you.

CURWOOD: And what about freshwater versus the ocean?

EVERS: Both sort of ecosystems, marine and freshwater, have the ability to methylate mercury and get up into the food web where it can cause some harm to us. And if we look at species of fish that we commonly eat in the Great Lakes region, for example, such as pike, or walleye, or bass, those are fish species that can commonly get over one part per million, which is fairly high.

CURWOOD: You looked closely at 14 different countries for mercury exposure. What was the percentage of people that had concerning levels of mercury in their hair?

EVERS: In those 14 countries that we examined, we found that 84 percent of the mercury in fish were over our threshold level that we used of .22 parts per million. That’s equivalent to one, six-ounce fish meal per month. And we also found in the hair samples of people around the world in these 14 countries that 82 percent of the hair samples exceed the EPA’s reference dose of one part per million.

CURWOOD: Now, last year, in 2012 that is, the US EPA promulgated the mercury in air toxic standards which will remove 90 percent of mercury from coal-fired power plants in the US over the next couple of years, so we’re making good progress in this country, but China and India are pretty busy with coal-fired power plants. How freely does mercury travel around the world, and what kind of emissions of mercury are we headed for if these new power plants in Asia continue to grow?

After the mercury and gold are bound together miners burn them so the mercury vaporizes and all that remains is pure gold. The miner can inhale the vaporized mercury. (Biodiversity Research Institute)

Along with artisanal gold mining, coal fired power plants are one of the biggest sources of global mercury emissions. (Biodiversity Research Institute)

EVERS: The US has really pulled together, I think, a very good role that will be successful in removing 90 percent or more of mercury from emissions from coal-fired power plants, and I think that can be done quite quickly. Probably a bigger looming problem is the mercury that’s getting up into the upper atmosphere, that global pool. And some of the key sources, for that mercury in the global pool, are China, India and coal-fired power plants. And so once that mercury is up into the global pool it does move over across the northern hemisphere, across North America, and it does deposit in North America. How much that will impact in US and Canada is still something that a lot of modelers are looking at. A lot of people are trying to better understand, but I’ll mention a study I had in the Great Lakes. We found that there was an uptick in the last decade of mercury in different species of fish, and birds, and other organisms. And so I think it is something we need to keep in our mind that even though we do clean up our backyard there is more work to be done.

CURWOOD: David Evers is the executive director of the Biodiversity Research Institute. Thanks so much for speaking to us from Geneva.

EVERS: You bet, Steve. Thanks for having us on the show. Thank you.

Related links:

- Report- Global Mercury Hotspots

- Biodiversity Research Institute

A New International Treaty on Mercury

Delegates and scientists from around the world met in Geneva, Switzerland to come up with a treaty that will reduce mercury emissions. (United Nations Environment Program)

CURWOOD: So in the face of rising concern about mercury pollution. There is some good news. On January 19, representatives from 147 nations meeting in Geneva finally wrapped up work on an international agreement to reduce mercury emissions in the environment. The treaty is officially known as the Minamata Convention on Mercury. It’s named for the Japanese city where a mercury-based chemical waste disaster took the lives of almost 2,000 people over the course of three decades starting in the 1930s. David Lennett is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, which participated in the negotiations.

LENNETT: It was tedious. We worked continuously around the clock for six consecutive days. But I think there was a collective sense that we really wanted to get this done. This was the fifth of five negotiations sessions. We were in a situation where we had to finish or fail.

CURWOOD: First, can you tell me what came out of the meeting in terms of gold mining?

LENNETT: At the country level, it requires governments to develop and implement national action plans to reduce the use of mercury. And these plans will focus on prohibiting the worst practices, the ones that really either waste mercury, or cause serious exposures to people involved in mining and their families. At the global level, the treaty also prevents certain supplies of mercury to go to small-scale gold mining – mercury from primary mining of mercury and mercury from chlorine plants that are closing, where large quantities of mercury remain -- cannot be sold for small-scale gold mining purposes on the marketplace. Therefore, we are starting to send the appropriate market signal to miners by reducing the availability of mercury and making it more expensive.

CURWOOD: Now what about coal-fired power plants?

Mercury treaty delegates (United Nations Environment Program)

LENNETT: There’s a mandatory scheme created for both new and existing sources. The new facilities have to meet best available techniques, best environmental practice requirements. With respect to existing facilities the treaty provisions are more lax. First of all, there’s up to ten years before requirements or controls have to be applied to existing facilities and then the menu of options available to governments to regulate these facilities is more - quote -flexible and therefore depending on the regime that governments choose, and how aggressive they want to be in setting limits on these facilities will determine how much reductions we get.

CURWOOD: What about China and India? These are places that are building a lot of coal-fired power plants. How likely is it that they’re going to want to ratify this treaty?

LENNETT: China already has emission controls on new and existing coal-fired power plants. They will need to do additional controls on other sources, but they’re already moving. And domestically, they have a special five-year plan, which actually mandates reductions in emissions of five heavy metals, including mercury. So the treaty is very consistent with their domestic policy framework.

CURWOOD: India?

LENNETT: India’s got a lot of power plants on the drawing board. And I have to assume that once the emissions language was ultimately agreed to, that they have every intent of ratifying the treaty. For India, I think access to financial and technical assistance will be important, and the best way for them to get it is to be a party to the convention.

CURWOOD: What was the position of the United States at these talks? And how likely is it that the US will readily sign on to the finished treaty?

LENNETT: I think it’s likely the US will try to ratify this treaty because their negotiating position was premised on the fact they could ratify this treaty without any new laws passed by Congress. So the treaty, in some respects, contains provisions which would allow them to do this.

CURWOOD: Now that this treaty is all done, what’s the timeframe for it actually to take effect?

LENNETT: The countries will meet again in Japan in October and sign the treaty. Once those signatures happen, we enter into a ratification period, and it requires 50 country ratifications before the treaty can come into force. So we’re looking at something like a 2016, 2017 time period before the treaty actually comes into force.

CURWOOD: There are a number of activists who say really this treaty is, well, rather weak. What’s your opinion?

LENNETT: I think there are strong parts of this treaty, and I think there are weak parts of this treaty. It’s a good start. We’re going to need to make improvements down the road to make it better. There’s enough in this treaty to be aggressive, but there’s also wiggle room to not do so much, and we’re just going to have to wait and see what happens. But the world’s better off having this document than not having it.

CURWOOD: David Lennett is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Thanks so much for taking this time with us today.

LENNETT: You’re welcome, my pleasure.

Related link:

A New International Treaty on Mercury

BirdNote ® Barred Owl

A Barred Owl in flight. (Photo: © Tom Grey)

CURWOOD: January 27th sees the first full moon of 2013, called the Wolf Moon by Native Americans. But in our BirdNote ® today, Mary McCann has a tale of an encounter with a different creature of the night.

[MUSIC]

A Barred Owl. (Photo: © Gregg Thompson)

MCGANN: Winter grips the land and dawn comes late. Our house sits at the edge of a field of grasses that are limp and broken, tunneled through by voles. I awake as two Barred Owls fly in tandem, low, by my windows, swift dark shapes against the grey and brooding light. How close they are – banking at the corner of the house.

Then, a loud and mighty smack! I find one owl lying on the floor of the porch, upside down beneath a window, a heap of feathers, one wing protruding, barely breathing. Shall I cover the bird with a blanket, put it in a box and keep it warm? Has it broken a wing, cracked its beak? Or shall I keep my distance, so as not to frighten it further? I decide to hold still and watch.

A Barred Owl perched in a tree. (Photo: © Tom Grey)

Minutes pass. Then the owl rights itself and moves its head. Our eyes lock. Dazed, it sits quietly, turning its head from time to time. More minutes pass. I leave to get my binoculars to study it more closely. When I return, it is gone. It has flown away.

Tonight, temperatures will plunge and a winter moon will illuminate the new snow. I’m Mary McCann.

CURWOOD: To see some photos of the barred owl, swoop on down to our website at LOE.org.

[Written By Chris Peterson

Musical selection from “When Comes December” composed and played by Tim Story, on A Winter’s Solstice, Windham Hill Records.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2013 Tune In to Nature.org January 2013 Narrator: Mary McCann]

Related link:

BirdNote ® Barred Owl

Coming up, some bats in the south are behaving, well, batty. Why this may not be good news for farmers is just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway, for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ivan “Boogaloo” Joe Jones: “Confusion” from Sweetback (Ubiquity Records 1999)]

Research Update on the Impact of BP Oil Spill

BP’s Deep Water Horizon rig on fire. (The Coast Guard)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Nearly three years after the BP Deepwater Horizon well gushed nearly five million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, there are still plenty of unanswered questions. And that is why more than 1,000 scientists and government officials recently gathered in New Orleans for progress reports on the extensive research that’s being done on this largest oil spill in US history. We called Mark Schleifstein, staff reporter for NOLA.com of the Times-Picayune in New Orleans for an update. We started by asking what the research shows about the two million gallons of toxic chemical dispersants that were used to break up the oil spewing into the gulf.

SCHLEIFSTEIN: There’s new research that does show that a combination of dispersant and oil is more toxic than either the dispersant or the oil on their own. Several of the papers did get into questions about both of the efficacy of using that as a treatment method – there were real questions about whether that was the reason the oil turned into tiny droplets. There’s now research that says that that might very well have been the fact that when warm oil hit the cold water at large pressures from being a mile below the surface and that caused it to turn into the tiny droplets even without the use of a dispersant. But what kinds of long-term effects...we’re still waiting to see what happens with that.

CURWOOD: Tell me about the seafood, nearly three years after the spill. What’s being found when it comes to the safety and palatability of Gulf seafood?

SCHLEIFSTEIN: Well, that obviously is a key question that keeps popping up. There were a couple of people at a public hearing that was held as part of this that were saying, we just don’t trust the Food and Drug Administration, we know what shrimp do and shrimp are moving through oily areas – we still have oil like in what’s called Bay Jimmy – those shrimp, they don’t just stop, they go out and somebody can catch them further out. But the Food and Drug Administration is sticking to its guns. An official at the conference made it clear that none of the samples they have taken of seafood that is on its way to market has shown any problems.

CURWOOD: Mark, tell me about the people who live in the Gulf. I know there’s been a lot of research on the health of residents and folks who were involved in the cleanup. Generally, what have the findings been so far?

Gulf oil spill on the beach (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

SCHLEIFSTEIN: Well, even two years after the spill, people are still dealing with a variety of mental health issues. And that seems to be the most significant problem that’s been discussed here. There also are reports of skin problems, people still having problems with breathing issues, coughing, those kinds of things...and headaches. A much larger study of people who worked in cleaning up the spill, which The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health has started, they have found biomarkers two years after the spill that are matching the oil from the BP well, still in the bodies of people who worked cleaning up the spill.

CURWOOD: What are the socioeconomic effects of the spill on the Gulf Region as a whole do you think?

SCHLEIFSTEIN: It really is a range of things. When you look at Alabama and Florida especially, it really destroyed their tourism business with the beaches. They’re coming back now. There was a significant effort by BP to clean those beaches. Basically, if they washed the sand, or sifted it to get out all the particles. When you get into the Mississippi Gulf Coast and Louisiana especially, you end up with more oil in wetland areas. There’s quite a few individual locations having problems getting rid of the remaining oil. Whenever there’s a storm, you end up getting new pieces of hardened oil coming to the surface washing around. You can dig down a foot and you end up with a liquid material that is weathered oil, but it’s still oil.

CURWOOD: Now what other research needs to be done here? What are we missing from the body of knowledge about this horrific oil spill?

Nola.com and Times Picayune reporter Mark Schleifstein (Photo nola.com)

SCHLEIFSTEIN: There are real concerns about things like porpoises, where there were many deaths over a couple of years. There are concerns about sperm whales, which actually tend to feed about 20 miles away from the oil spill site. The other things people are looking for are answers about birds especially, shore birds and birds that fly over the Gulf, and what long-term effects there may be for them.

CURWOOD: Mark, tell me, what’s the latest settlements for BP and Transocean?

SCHLEIFSTEIN: So far, we’ve got two plea agreements – one from BP and one from Transocean for criminal charges. BP has agreed to pay $4.5 billion dollars to deal with both Clean Water Act criminal issues and Securities and Exchange criminal issues. Transocean has agreed to about $1.4 billion dollars, so that part’s done. BP has entered into a settlement agreement with private claimants, and that settlement agreement basically is expected to result in a minimum payment of $8.7 billion dollars that would pay for medical, economic and fishing claims. And then you’ve got the Natural Resource Damage Assessment process and the estimates of that are as much as another $20 billion dollars. There’s a lot of speculation that there will be a settlement before the first part of this legal process goes to trial, which is supposed to be on February 25th. But at the moment, the negotiations of that potential settlement seem to be at a standstill.

CURWOOD: Mark Schleifstein. is a reporter for NOLA.com of the Times-Picayune in New Orleans. Thanks so much, Mark.

SCHLEIFSTEIN: Thank you.

Related links:

- More from nola.com about the BP spill research meeting

- More about Mark Schleifstein

[MUSIC: Kermit Ruffins/Rebirth Brass Band “It’s Later Than You Think” from Mardi Gras 09 (Basin Street Records 2009)]

America's Bats on the Brink

A Little Brown Bat with White Nose Syndrome (photo: Jonathan Mays, Wildlife Biologist, Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife)

CURWOOD: Normally, bats hibernate through the cold winter months. But this winter, visitors to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina have seen bats out and about. Scientists haven’t confirmed the cause of this strange behavior, but the primary suspect is the devastating bat disease, white-nose syndrome. Joining us now to discuss the news, is Katie Gillies, Imperiled Specious Coordinator at Bat Conservation International in Austin, Texas.

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth.

GILLIES: Thank you.

Katie Gillies holding a bat (photo: Bat Conservation International)

CURWOOD: So Katie, tell us, what kinds of behaviors are they seeing in these Smoky Mountain bats?

GILLIES: The bats should be underground nestled in their caves sleeping away the cold winter months. Unfortunately, they’ve been seeing some very erratic behavior, which involves bats flying around up and down the trails, up around all the buildings, and I think they’ve even had a bat fly into a human being. And this is behavior that’s usually indicative of a sick bat.

CURWOOD: So what do scientists think is causing this behavior?

GILLIES: Well, what they think is causing it is a disease known as white-nose syndrome. And this a new disease here in North America, that’s only been on the landscape for about the past six years. It is a fungal infection. It’s a really aggressive fungus. It was recently named Geomyces destructans because it is a very destructive fungus that invades the bats’ wings and nose and ears, their really thin dermal tissue. The fungus goes in and basically breaks down that tissue. And this is very irritating and disruptive to the bats. The bats’ immune systems are suppressed in the wintertime, and they’re in a deep state of torpor. So their breathing is low, their heart rate is low, their immune system is very unresponsive. This causes them this irritation, and this disruption causes them to wake up repeatedly through the winter months. This is very costly to them. Waking up uses critical fat reserves, and what happens is they’re dehydrated, they’re undernourished, they’re malnourished. And they leave their caves or their mines, wherever they’re hibernating, in search of food and water. And it’s very harsh for them out in the winter, that type of condition, and they end up dying.

CURWOOD: Now what bat species are affected?

GILLIES: Right now we have nine species of bats that are confirmed either with the disease or the fungus. And almost all those species are seeing high fatality rates. The endangered Grey bat just earlier this year was confirmed with the disease, there’s about a one to three year latency period when the disease is first documented before a serious fatality would start to occur. So we haven’t seen any fatalities from Grey bats yet. We may start to see those this winter though. The endangered Indiana bat has also been confirmed with the disease and we are seeing significant fatalities there. The Little Brown bat, which was once the most common bat in North America, is seeing such significant population declines that it’s been petitioned for listing under the Endangered Species Act.

A Little Brown Bat with White Nose Syndrome (photo: Ryan von Linden/New York Department of Environmental Conservation)

CURWOOD: Describe the extent of the white-nose epidemic for us. Where did it begin and how far has it spread?

GILLIES: White-nose was first discovered in a cave system in Upstate New York back in 2006, 2007. And it has spread voraciously from there. It currently occurs in 19 states and four Canadian provinces. It’s as far south as northern Alabama and as far west as eastern Missouri. The fungus that causes it has also been confirmed in Iowa and Oklahoma but the disease itself has not been confirmed in those states.

CURWOOD: Where did this fungus come from?

GILLIES: Well, the fungus came from Europe. It traveled over here from Europe, a single point source of it and has expanded from there.

CURWOOD: So how are bat populations doing nationally here in the US?

GILLIES: I’m afraid they’re faring terribly here in the US. Many, many sites are seeing up to 99 percent fatalities there. So these are sites that...

CURWOOD: Wait. You said 99 percent? That sounds like extinction.

GILLIES: Yes. We are witnessing what may very well be a significant extinction event, something that our generation has never encountered before. And it’s terrible. It’s terrible to witness. There are biologists that go to these caves year after year to monitor and count the bats and see how the bat populations are doing and they’re walking into these caves that used to have 100,000 bats in it, and they’re just seeing a handful of them now.

A Little Brown Bat (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: For many people, bats are seen as pests. Why should we be so worried about their decline?

GILLIES: Ecologically, bats are the primary predator for night flying insects, and we can estimate that a single bat can consume four to eight grams of insects through the course of a night, and we don’t really know what the loss of millions of bats on a landscape is going to mean ecologically. We can’t really fathom that ripple effect. But because they are such significant controllers of these insect pests, they also impart some significant economic benefits to people. There was a paper that came out in 2011 in Science that looked at the math on this and, so like I said, if a single bat can consume up to eight grams of insects each night, that means that, you know, millions of bats...right now they estimate that at least 5.7 million bats have been killed from white-nose. So 5.7 million bats can consume 7,500 metric tons of insects annually, and those insects are currently not being consumed if we’ve lost 5.7 million bats on the landscape.

CURWOOD: And these are insects we don’t particularly like, I gather.

GILLIES: Well, there’s variety in a bat’s diet. But certainly it’s well documented that bats consume agricultural pests, and not having them can be real detrimental to our agricultural ecosystems. And the same paper in Science that came out in 2011 estimates that ecological services of bats in agricultural services impart a $23 billion benefit to US farmers every single year.

CURWOOD: So that’s more than a farm subsidy program for many crops is what you’re saying.

GILLIES: Yes, it’s quite a lot.

CURWOOD: Katie Gillies is Imperiled Specious Coordinator at Bat Conservation International in Austin, Texas. Thanks for joining us, Katie.

GILLIES: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- White Nose Syndrome

- Bat Conservation International

[MUSIC : Lukeing Forward “Mysterious Bats From the Slums” from Mysterious Bats From the Slums (Next Dimension Music 2008)]

Can Prairie Dogs Save Mexico's Prairie From the Desert?

Prairie Dogs (Photo: Encyclopedia of Life)

CURWOOD: Life on our planet is incalculably diverse, and organisms have evolved to fill every available habitat. But ecosystems are interdependent, and if you remove a species, you can upset a whole balance. Today, reporter Ari Daniel Shapiro brings news of one particular animal and its vital role in Mexico’s prairie.

SHAPIRO: Gerardo Ceballos is only 54, but he feels like he’s racing against a clock.

CEBALLOS: I don’t have so many years left.

SHAPIRO: Ceballos is refusing to let his time run out before restoring a special place in his native Mexico.

Our story actually starts well before Ceballos was born – back in the 1800s – when cattle ranching was surging through the prairies of North America, from Manitoba, Canada all the way down to Chihuahua in Mexico. And this is where the real heroes of our story come in – though, at the time they were no heroes to the cattle industry. I’m talking about Cynomys ludovicianus, or black-tailed prairie dogs.

CEBALLOS: Prairie dogs are really nice animals. They are the size of a relatively large cat.

SHAPIRO: They’re a kind of squirrel that can stand on two legs to survey the grasslands for predators. And prairie dogs thrived in North America.

CEBALLOS: Probably 30 billion prairie dogs used to live in those grasslands.

SHAPIRO: But ranchers came to believe that prairie dogs were competing with their cattle for grass, and that cows and horses were breaking their legs by stepping into the prairie dog burrows. Opinions are divided on how serious these problems were. But many ranchers were convinced – and with support from the US government – they launched an all-out war on the prairie dogs. One weapon of choice was a kind of nerve toxin.

CEBALLOS: It’s a poison that will produce convulsions, a failure of the lungs and the heart. It’s a really nasty thing.

SHAPIRO: Tablets of this stuff were tossed down into the burrows, where they produced a toxic vapor that killed everything in its wake.

CEBALLOS: We are talking about probably billions of prairie dogs.

SHAPIRO: Billions that were killed by this toxin?

CEBALLOS: By poisoning and then by the advance of agriculture. It has been one of the most dramatic, drastic exterminations of an animal by humans.

SHAPIRO: Within 50 to 60 years, prairie dogs were eradicated from 98 percent of the area they used to call home; from 30 billion animals to 1 or 2 million.

Without prairie dogs, the prairies transformed. In Mexico, the desert moved in – thanks to a shrub called mesquite. It pushes a deep root into the Earth, sucking up water, and it attracts small animals that devour the grasses ringing the mesquite.

Prairie dogs can’t stand the plant. It blocks their view of the horizon where a predator might be lurking. So they do whatever they can to get rid of it. They chew up the roots. They suck on the stems. They run around like little gardeners, keeping the desert at bay.

So with very few prairie dogs left, the mesquite helped create desert scrubland until there was little grassy prairie remaining. And with the arrival of the desert...

Cynomys ludovicianus Black-tailed Prairie Dog (Photo: Arthur Chapman)

CEBALLOS: You lose the ability of this landscape to maintain wildlife and plants. But also the scrubland is not good for cattle.

SHAPIRO: So the land no longer supported the very ranching it was altered for.

Let’s fast forward now to the summer of 1987, when Ceballos was in the middle of his doctorate in Arizona. He and his wife were driving back to Mexico through what used to be the grasslands, in Chihuahua, an area he’d never visited before. It was pretty much all desert. But then one day...

CEBALLOS: We were not prepared mentally to see what we saw.

SHAPIRO: Grasslands waving in the wind. This area had been spared.

CEBALLOS: It was mind-blowing because all the way to the horizon – there were prairie dogs and prairie dogs and prairie dogs. And then the next day we saw badgers. Badgers are very rare in Mexico. Golden eagles are also very rare in Mexico, and we saw more than 20 there in one single day. It hit me immediately the idea that prairie dogs should have some role.

SHAPIRO: Some role in making the prairie possible. In the last 20 years, as an ecologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Ceballos has shown that prairie dogs are a keystone species. That is, everything in the grassland ecosystem depends on them. Their burrows provide shelter for small mammals. Predators – like coyotes and hawks – feed on prairie dogs. These days, Ceballos is resuscitating the prairies, by reintroducing the prairie dogs.

CEBALLOS: Within one year, they destroy most of the mesquite.

SHAPIRO: He’s also reintroducing black-footed ferrets – a species that hasn’t been in Mexico for at least a hundred years, pronghorn antelopes, bighorn sheep, wolves - even bison, which he’s getting from the US. He’s partnered with environmental groups and the government to create a reserve that protects these species, and then offers local people ways to benefit economically from the grassland. And gradually, a portion of the Mexican prairies are coming back.

CEBALLOS: A good scientist has to do good research, but then has to translate it into action. There is no way that we can continue just being like historians – recording all the things that we are losing, instead of becoming actors. Now, my main objective in life is to save as many species of plants and animals as I can.

(Encyclopedia of Life)

SHAPIRO: Which is why – even at 54 – Ceballos feels he doesn’t have a moment to waste. He has a legacy to leave his country. For Living on Earth, I’m Ari Daniel Shapiro.

CURWOOD: Our story on prairie dogs is part of the series, One Species at a Time, produced by Atlantic Public Media with support from the Encyclopedia of Life. To see some photos follow the trail to our website at LOE.org, or check out our Facebook page. It’s PRI’s Living on Earth.

Related links:

- More about the Encyclopedia of Life

- More about Ari Daniel Shapiro

[MUSIC: Brad Mehldau “The Falcon Will Fly Again” from Highway Rider (Nonesuch Records 2010)]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth, NASA has come up with an intriguing way to deal with those things you can’t easily recycle.

MAN: The plastic that’s in there melts and encapsulates the waste, and what you have is a hard plastic tile with most of the other waste materials embedded inside of it.

CURWOOD: Space trash into mission treasure. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Annie Sneed, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and check out our Facebook page, it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at justeatorganic.com. Support also comes from you our listeners. The Go Forward Fund and Pax World Mutual and Exchange Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at PaxWorld.com. Pax World, for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth